Luisa Cunha: Make Art Do Nothing Make Art Do Nothing Make Art Do Nothing

Joshua Decter

Photography by Daniel Malhão.

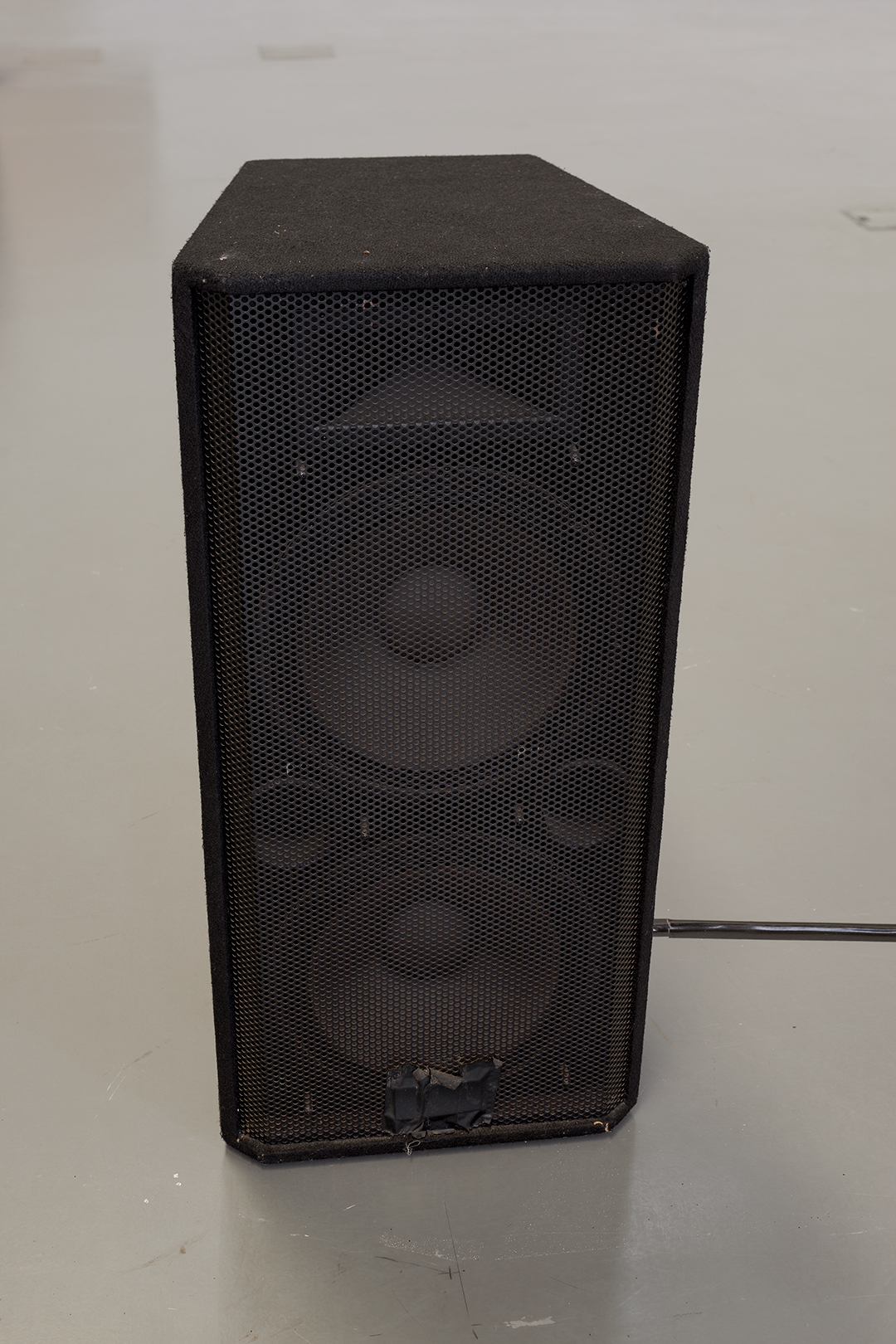

Luisa Cunha, Partitura #5, 2022. Sound text; 55 min, loop. Loudspeaker RoHS PA 252, audio cable; dimensions variable. Coll. of the artist. Photo: Daniel Malhão, courtesy of the artist and EDP Foundation / MAAT.

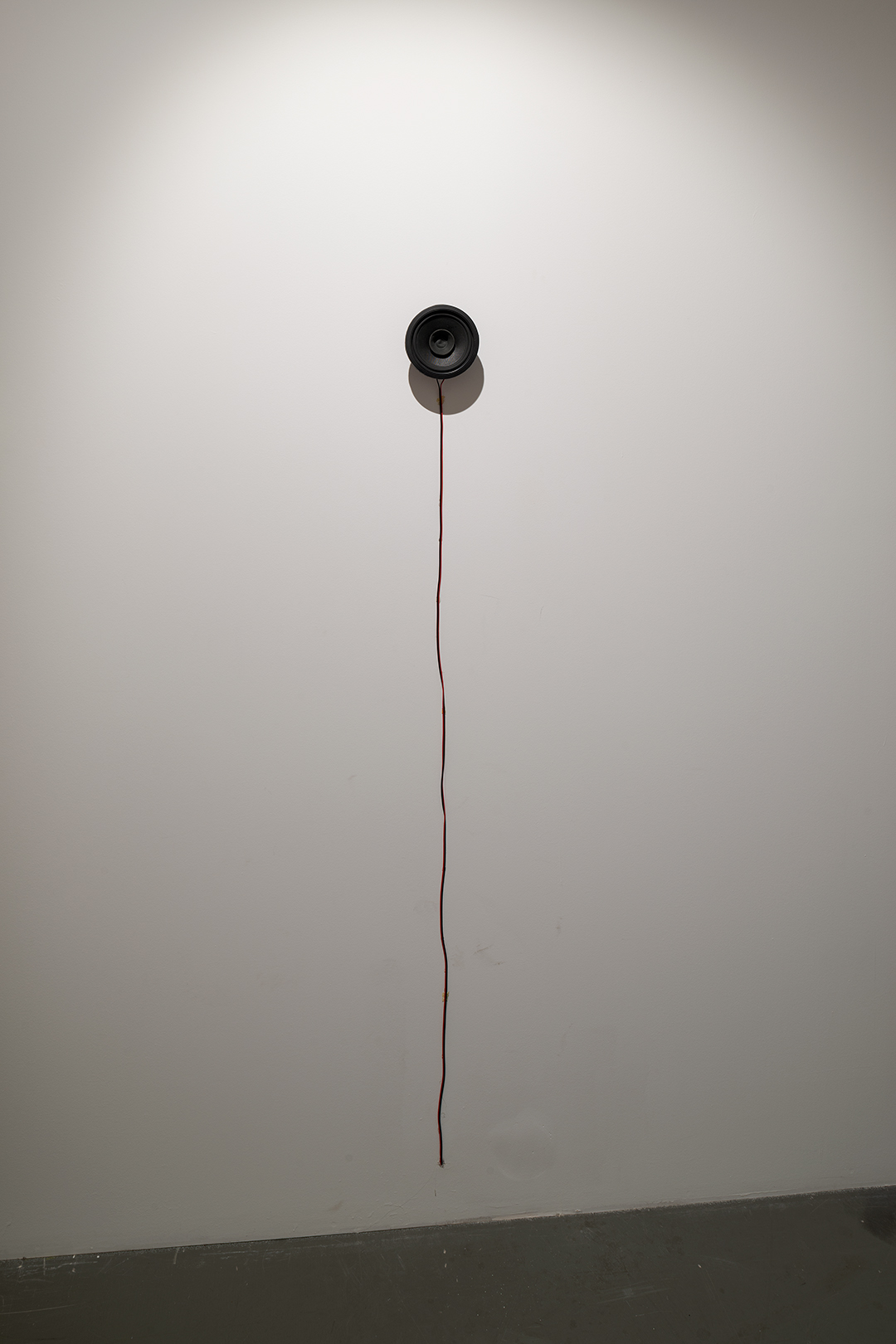

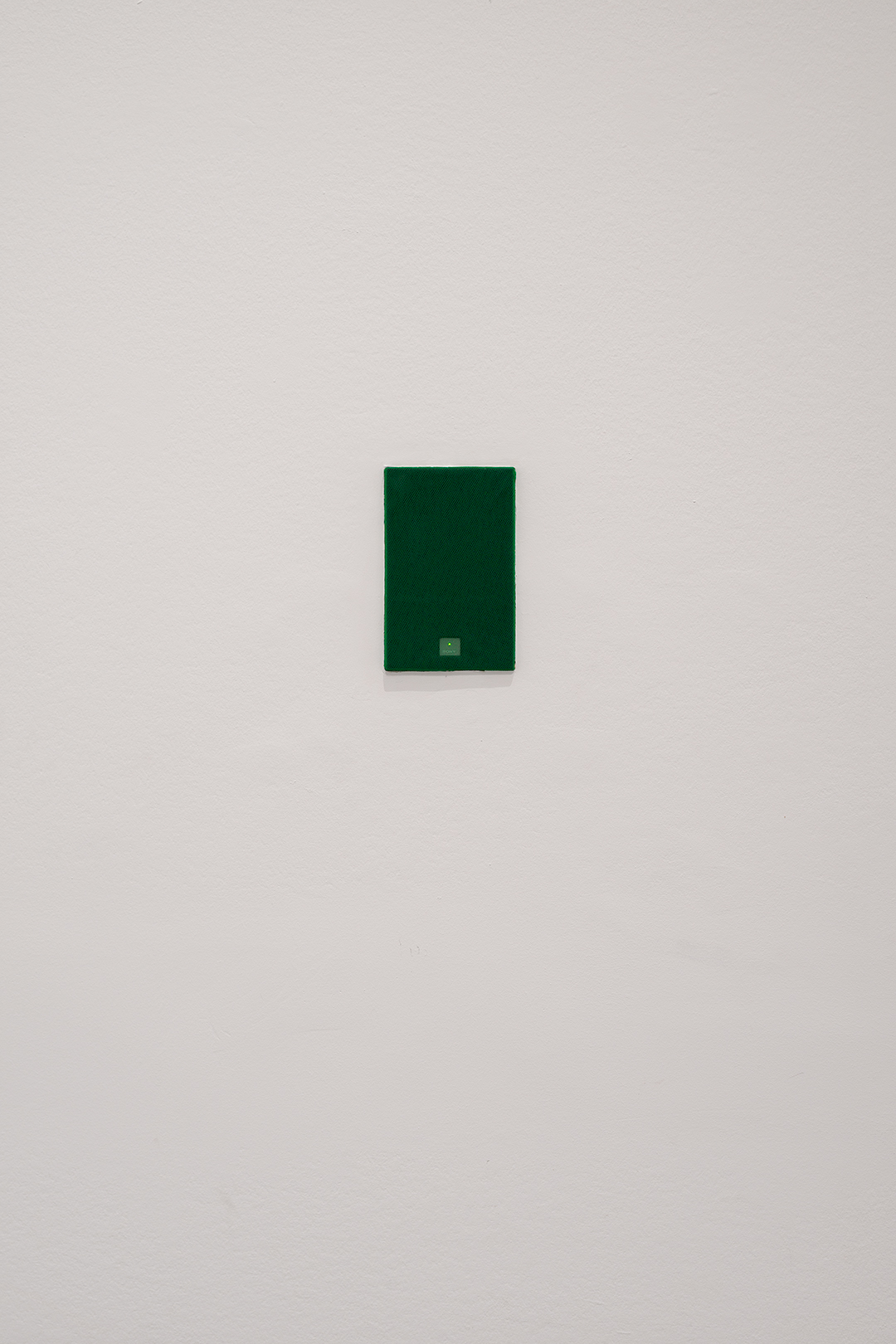

Luisa Cunha, Field of View, 2010. Sound text; 28 s, loop. Speaker driver, audio cable; dimensions variable. Coll. EGEAC – Câmara Municipal de Lisboa. Photo: Daniel Malhão, courtesy of the artist and EDP Foundation / MAAT.

Luisa Cunha, Ali vai o João, 1996. Sound text; 36 s, loop. Window, chair, loudspeaker; dimensions variable. Coll. of the artist. Photo: Daniel Malhão, courtesy of the artist and EDP Foundation / MAAT.

Are you there? Can you read me? Hello.

Call me crazy, but I’ve always been fascinated by art that doesn’t seem to be art at first blush. The sort of art that does not call attention to itself as art. The kind of art that makes us rethink our assumptions about what art is supposed to look, feel, sound, and even smell like. Art that is a question mark (about art). The sort of art that might seem to slip away into the quotidian realm of non-art, and by doing so, prompts us to recall that art is as much a part of the quotidian realm as it is distinct from the everyday. An art that reveals the paradox that is art. An art that is also meta-art; i.e., art that makes us think about what art is, how we define it, and how/where it can happen. Luisa Cunha’s art does all of this and more. My sense is that Cunha welcomes the notion that art can be found wherever one might happen to encounter the potential for art, even if it happens to be a voice we hear in a room. I am thinking, of course, of Cunha’s “textos sonoros” (→ 1), wherein we might hear the artist’s voice repeating her words and phrases which travel through the air within a specific place, and yet not immediately associate those sounds, that spoken language, with art. This is related to the fact that the sound texts de-emphasise materiality in favour of the perceptual faculty of hearing and the cognitive processing of what we hear, and how we hear it. These works are largely experienced sonically, with her voice, her words, rescripting places in subtle, ambiguous, and indirect ways.

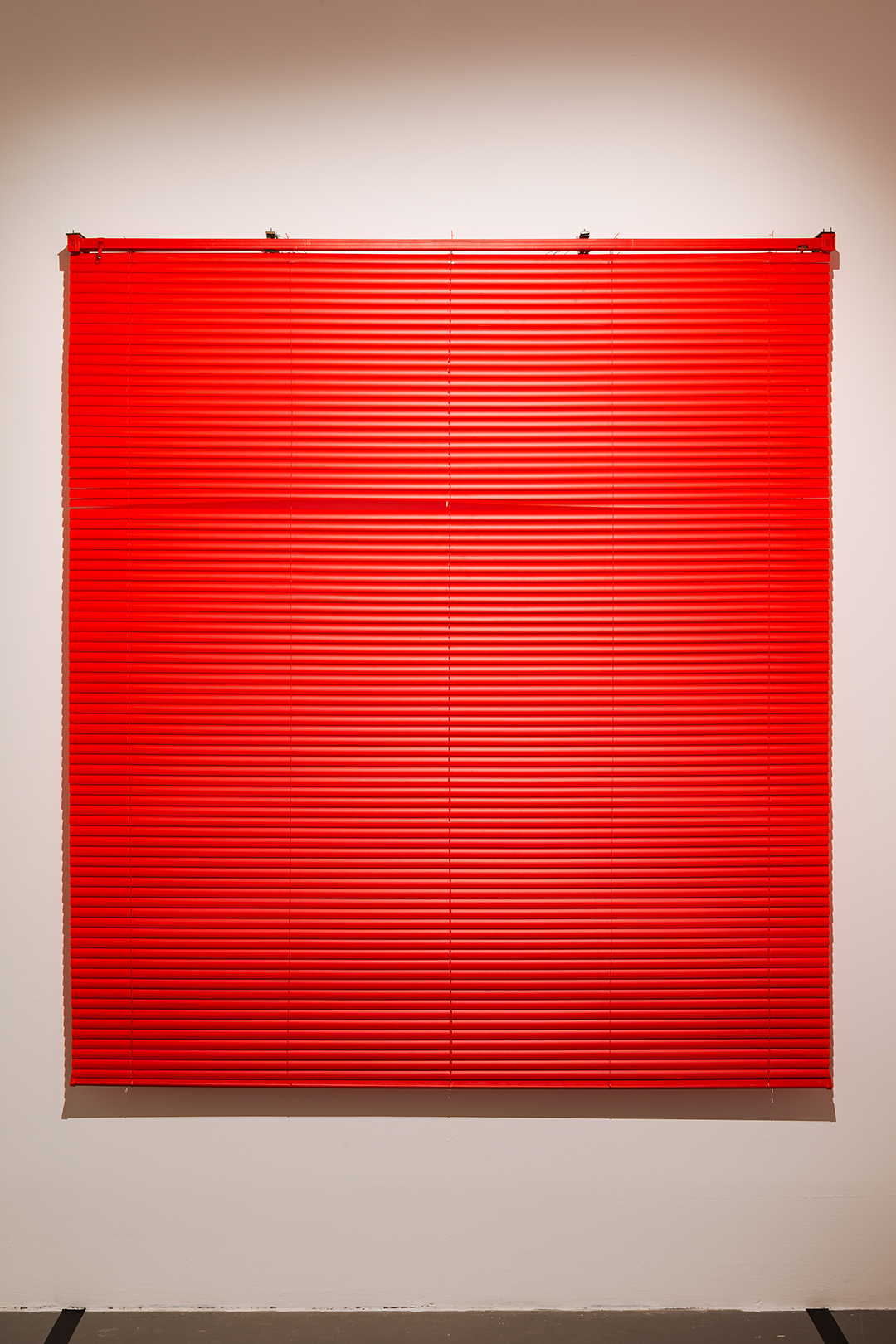

Luisa Cunha, Dirty Mind, 1995. Sound text; 13 s, loop. Red Venetian blinds in PVC, speaker driver; 161 × 175 × 5 cm. Coleção de Arte Contemporânea do Estado, Portugal. Photo: Daniel Malhão, courtesy of the artist and EDP Foundation / MAAT.

“I do enjoy creating an ironic, critical distance from my work. It happens in a very natural, intuitive way. It is a sort of a game to me in which life is in fact more important than art. I do really enjoy it. In that sense I acquire a double identity.”

Luisa Cunha, email to Joshua Decter

Cunha’s sound texts deliver fragmented narratives (perhaps autobiographical, perhaps not) in relation to the spatial conditions of the site in which they have been produced and installed. Repetition is part of the key logic of many of these works. They seem to inhabit a hybrid kind of identity: at once ephemeral as audiobased works, while also being about their technological means of existence (such as electronics, loudspeaker, and other material elements). And they encompass a performative aspect – the performance, so to speak, of the artist’s voice. Who is being addressed? Although we hear the artist’s voice, is it representative of the artist, a character the artist is playing for audiences, or both? A doubling of identity, at once self-referential and generic. This is related to the narrative ambiguity, or counter-narrative aspects of these works, wherein we hear what could be understood as the fragment of a story.

Luisa Cunha, Untitled (Do nothing), 2009. Sound text; 12 s, loop. Loudspeaker; dimensions variable. Coll. of the artist. Photo: Daniel Malhão, courtesy of the artist and EDP Foundation / MAAT.

Yes, it is possible to connect Cunha’s practice to various histories of sound art, wherein various degrees of dematerialization occur to amplify engagement with the aural experience, transforming viewers into listeners and receivers. And yet, as I suggest later, the materiality of the technological equipment that produces and transmits the sounds of the texts being read by the artist is also crucial, since that equipment is emblematic of very specific formal artistic decisions that Cunha is making; she would like us to notice that there are speakers and wires, but not fixate on these elements. The equipment is a means to an end, not an aesthetic end in and of itself. The equipment might be characterised as para-sculptural. We might also propose that Cunha’s art happens in that interstitial zone between the equipment that transmits the sound of the voiced texts, and the voiced texts themselves. This returns us to Cunha’s deliberately modest, quotidian aesthetics, and the extent to which it is conceivable that some people might hear Cunha’s works but not understand, at first, that what they are hearing is art. And that’s ok. After all, not every encounter with words transmitted through space by a voice is necessarily art; until one discovers that it is art.

“A month ago I was nominated to participate in a Do Nothing International Contemporary Art Contest. I was the winner. I am happy.”

“A month ago I was nominated to participate in a Do Nothing International Contemporary Art Contest. I was the winner. I am happy.”

“A month ago I was nominated to participate in a Do Nothing International Contemporary Art Contest. I was the winner. I am happy.”

“A month ago I was nominated…”

We hear a voice, presumably Cunha’s, emanating from a speaker, repeating this line. This is Untitled (Do Nothing), a 2009 sound text. The work originally comprises a speaker, a CD-player, an amplifier, and a recorded voice. It was initially presented as an outdoor installation within the context of the exhibition Cinco Estrelas at the Arte Ilimitada art school, in Lisbon. Like many of the sound texts, this work has been reduced to the essential ingredients: the basic equipment that delivers the voicing of the text. Cunha does not want to hide the technical apparatus, but neither does she want to fetishise it. It is what it is. What you see is what you get, and what you hear is what you hear: “A month ago I was nominated to participate in a Do Nothing International Contemporary Art Contest. I was the winner. I am happy.” A hilarious and affectionate poke at the self-seriousness of art. There is something almost neo-Dadaist about Cunha’s playful irreverence, and indeed, doing nothing can also be art.

Luisa Cunha, 1680 metros, 2020–2021. Sound text; 26 s, loop. Loudspeaker; dimensions variable. Coll. of the artist. Photo: Daniel Malhão, courtesy of the artist and EDP Foundation / MAAT.

Luisa Cunha, Sweet bloody life, 2009. Sound text; 58 s, loop. Loudspeaker; dimensions variable. Coll. of the artist. Photo: Daniel Malhão, courtesy of the artist and EDP Foundation / MAAT.

“Regarding a decision to make art… in fact I decided nothing… I just kept on doing things as things were constantly coming to my mind and eyes… aware that I could always stop and do nothing.”

Luisa Cunha, email to Joshua Decter

Cunha’s art is as much about art’s possibility of being as it is about this or that issue, this or that idea, this or that feeling. Her art may or may not be about her, me, or anyone else. When we encounter the sound of a woman’s voice emanating from a single speaker installed in a space, repeatedly uttering “Nao” in a variety of patterns and manners, what are we to think? In this “texto sonoro”, we will never really know why the artist is repeatedly saying “no.” But the repetition does amplify our attention to the meaning of the word “no,” and what “no” sounds like in several variations, even to the point where the word might begin to lose its meaning. Endless, looped repetition as an act of linguistic absurdity, wherein a word becomes just a voice, a sound, potentially estranged from meaning or narrative. To whom is “no” being said? What is being denied? The presence of the viewer (us)? The presence of art… as a kind of playful negation of art? No, yes, maybe. If one thinks of “no” as negation, then we can link this work by Cunha to a history of modernism in which various permutations of “no,” of negation, can be identified. Is Cunha, paradoxically, saying no to the artwork itself? The artwork that cancels itself? No as a protest (against art)?

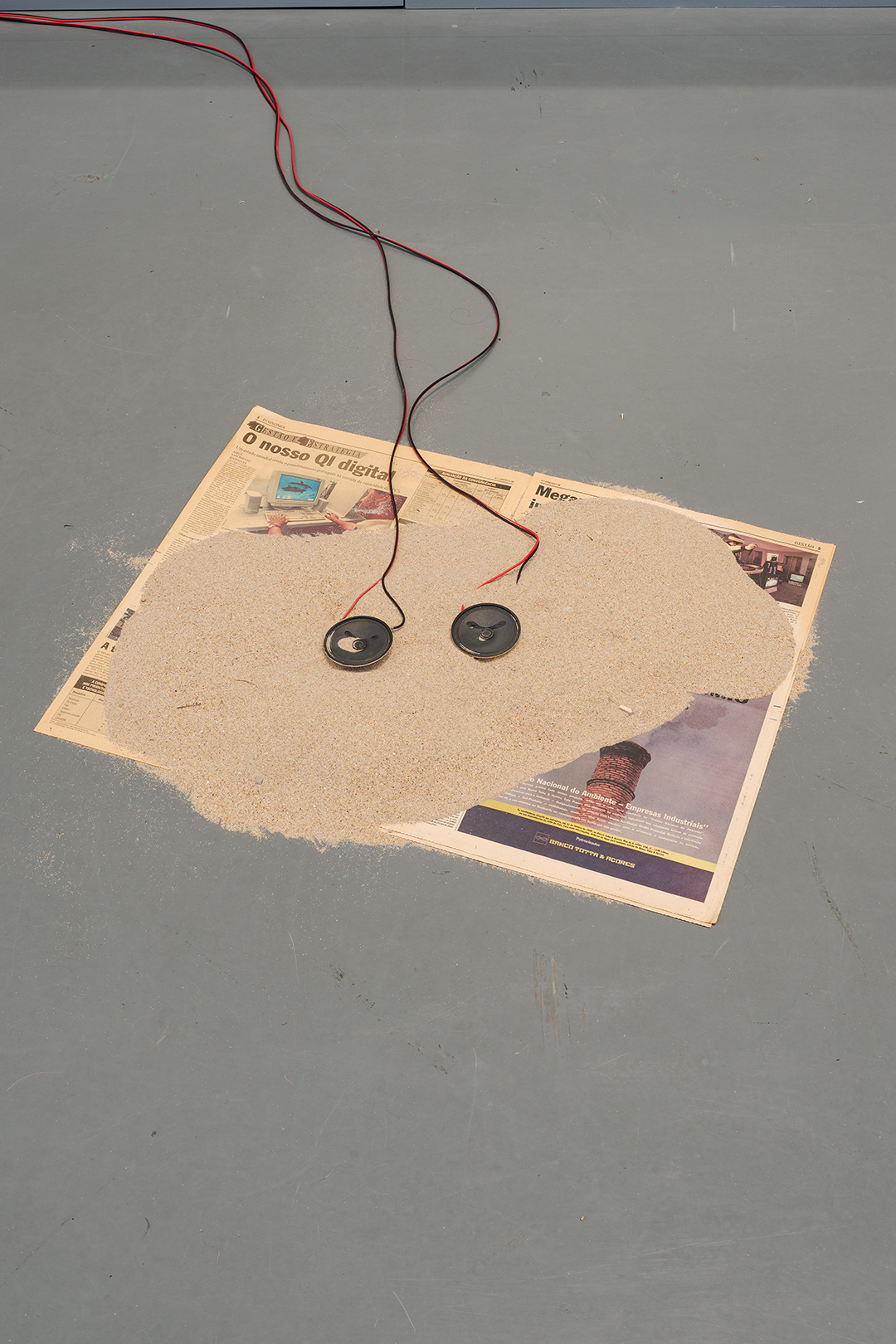

Luisa Cunha, Sem título (Areia), 1993. Sound; 61 min 6 s, loop. 2 speaker drivers, audio cables, sand, newspaper; dimensions variable. Coll. Fundação de Serralves – Museu de Arte

Contemporânea, Porto (acquisition: 2009). Photo: Daniel Malhão, courtesy of the artist and EDP Foundation / MAAT.

I believe that the first solo Cunha exhibition I saw was Partitura #5 at the Appleton space in Lisbon, in early 2022. My immediate impression of that sound installation was that the artist was dissembling the gallery space with sound. A sonic intervention into the gallery space. The injection of what seemed to be construction noises (real and/or simulated) into the pristine white cube, perhaps as a type of context/site-specificity. At first, I imagined that the sound was emanating from the street, and that the artist had somehow transposed the everyday sounds of Lisbon’s incessant architectural and urban renovations into the inviolable realm of the art space… but then I began to perceive that the sound was like a phantom limb of some (fictive?) structural work that might have been performed in that gallery space at another moment in time. In other words, it was a record of the building of the gallery itself, which to me relates to histories of institutional site-specificity in art, for instance in the work of Michael Asher, who utilized the intrinsic characteristics of gallery and museum spaces to subtly alter those spaces, thereby rethinking what sculpture might be and amplifying our awareness of the contextual frames of art. I felt a link to this art ethos in Cunha’s Partitura #5, in the sense that she was also endeavouring to make us more aware of the contextual frame in which art happens. And as with the sound texts, there was the possibility of a story being communicated through the audio; at least the possibility of a narrative, or fragments of a narrative that we are invited to reassemble into possible associative meanings. And then there is the equipment itself: the speaker, the apparatus of sound projection with its electrical cord that winds its way into the wall of the gallery space like an umbilical cord. The speaker is a utilitarian object that also performs as a ready-made sculpture, so to speak. At once an apparatus and a sculptural object.

And then I encountered a notice – signed by Cunha – that was affixed rather casually to the wall, and which reads: “The gallery will be undergoing works from this date. These will be kept as brief as possible, thank you for your understanding of any inconvenience caused.” At first, I did not understand the function of the notice; I thought that the gallery would be undergoing some literal process of renovation. But I had been duped, in the best possible way. For indeed the renovation of the gallery space was a virtual, immaterial, dematerialised renovation… achieved sonically. Perhaps the notice was a tongue-in-cheek gesture to destabilise viewers, to make us question what was happening in that place. It is of course rare that an artist would post such a notice during their exhibition, so one might understand it to be a provocation of the audience, as well as a rather humorous gesture of critique regarding the authority of the artist (and of art)?

|

|

|

|

Luisa Cunha, Do what you have to do, 1994. Sound text; 17 s, loop. 2 speaker drivers, wire, audio cables; dimensions variable. EDP Foundation Art Collection. Photo: Daniel Malhão, courtesy of the artist and EDP Foundation / MAAT.

|

|

|

Luisa Cunha, Artista à procura de si própria, 2015. Sound text; 3 min 19 s, loop. Loudspeaker; dimensions variable. Coll. Figueiredo Ribeiro, Abrantes. Photo: Daniel Malhão, courtesy of the artist and EDP Foundation / MAAT.

|

This brings to mind the 2016 photographic (or photo-performative) work Body Corner, in which we observe Cunha standing with her back to the camera in the corner of an interior of what is likely an art space – her arms outstretched as if to demarcate the literal relation between her body and the space. The degree-zero of artistic presence. In terms of artists who deployed themselves performatively into spatial situations in order to reimagine and disrupt normative relations between the body, architecture, and social space, one thinks of precursors of the 1960s and 1970s, such as Bruce Nauman, Marina Abramović, Chris Burden, Carolee Schneemann, and Dan Graham. In Body Corner, Cunha appears to be at once embracing the conditions of that spatial situation while also refusing the gaze of the camera, which might be considered an attempt to defy a certain kind of bodily objectification, as well as to interfere with associations with self-portraiture. Is the identity of the artist here nearly indistinguishable from the identity, so to speak, of the corner of that room? The body as architecture, and architecture as corporeality? The subtle remapping of space is also evident in Limite (2012), one of the artist’s self-described interventions, which comprises a yellow line made at the junction of a cement wall and floor. The work invokes histories of post-minimalism, site-specificity, and ephemeral/transitory art, and it rather matter-of-factly marks the literal architectural limit of where floor and wall meet. It is an artwork that is contingent upon the extant architecture, amplifying the existing conditions of the space. It is an artwork on the verge of disappearance into its site of iteration, which we can relate to Cunha’s use of sound… which as a non-physical and non-visual phenomenon is both there and not there, at once present and absent.

Imagine walking into a bathroom, or any kind of room, and hearing a woman’s voice repeating: “Are you there? Can you hear me? Hello!” One might think of Cunha’s Hello! (1994) as an embodiment of what all artists wish to express with their art: the search for an audience, for a public, for participants, for a social encounter, for some sort of engagement. The fact that it is the artist herself who is saying these words makes it more poignant. Cunha seems to be endeavouring, in a deadpan, humorous way, to verify if anyone is actually there for her, and for her art. Isn’t every work of art, as with every work of music, a greeting to a prospective listener, a potential receiver, a hypothetical viewer? And is there art at all if there is no one there to hear the art? Other interpretations are possible, of course, and that’s the point of Cunha’s poetic discourse – it is open to multiple receptions and (mis)understandings. Perhaps it is as simple as the artist having a bad connection during a phone call: “Are you there? Can you hear me? Hello!” Or she could be alluding to a frictional situation with a friend or lover who is just not listening: “Are you there? Can you hear me? Hello!” Perhaps it is a deep existential crisis, wherein one asks oneself: “Are you there? Can you hear me? Hello!”

“The ‘you’ is always the visitors and me.”

Luisa Cunha, email to Joshua Decter

In Do what you have to do (1994), two speakers suspended from wires play a 17-minute loop of a recorded voice – a voice that seems to have been digitally distorted as if to hide the identity of the speaker – robotically uttering a sequence of repeated and closely related phrases that seem to blend into each other to produce a mutated language. An excerpt: “Do what you have to do / What is it that you do / You do have to do what / You do have to do / You do what you have to / Do I have to do what I have to do / Do what you have to do / What is it that you do ….” Here, Cunha produces a linguistic and textual absurdism: language has the potential to mean so many different things that we (the collective “yous” being addressed) are cast adrift into a sea of ambiguity. Who is the “you”? Who is the “I”? Us, the artist, or are these just abstract words – floating signifiers? There is a tautological dialogue – and confrontation– produced in which the “you” and the “I” are at once distinct and indistinguishable. The subject of the speech act and the object of the speech act sound as if they are being conflated. It is as if we are eavesdropping on a lover’s quarrel with no beginning and no end – perhaps even a sado-masochistic encounter. We might also suggest that Cunha is engendering a kind of post-poetic sonic poetry; accidental poetry might be another way to express it.

Luisa Cunha, The Hat, 1997. Sound text; 47 s, loop. 4 speaker drivers, audio cables; dimensions variable. Coleção de Arte Contemporânea do Estado, Portugal. Photo: Daniel Malhão, courtesy of the artist and EDP Foundation / MAAT.

Luisa Cunha, Drop the bomb!, 1994. Sound text; 53 min 54 s, loop. Speaker driver, audio cables, wire, table and chairs; dimensions variable. Coll. Caixa Geral de Depósitos. Photo: Daniel Malhão, courtesy of the artist and EDP Foundation / MAAT.

What is a life? What is a life in art? What is art in life? How to represent a life in art, and art in life? With sly wit, Cunha might have a tongue-in-cheek answer to such questions in her work entitled CV, a limited-edition print from 2018. In this deadpan, humorous numerical record of the artist’s exhibitions from 1993 to 2018, we are only offered the year in which the exhibition occurred, and the years are repeated – green numbers over a white background – when there are multiple shows within that same year, as in: “... 2004 2004 2004 2004 2003 2003 2002 2001 2001 2001 2000 2000 2000 1997 1997 1997 1996 1996 1996 1995 1994 1994 1993 1993”, and so on and so forth.

According to CV, 2010 was an especially busy year for Cunha, as the date is repeated 15 times. 2018 appears 13 times. One imagines that in conceptual terms, Cunha could expand this work every year. It somehow reminds me of the ethos of On Kawara’s “I Am Still Alive,” or even Marcel Duchamp’s tongue-in-cheek, autoretrospective work, La Boîte-en-valise.

What could be a more appropriate wry commentary on this era of industrialised contemporary art production, and along with it, the hyper-professionalisation of the artist? The curriculum vitae as artwork as ironic riposte to careerism. Are we nothing more than our curriculum vitae – the sum of our professional projects? Sometimes it feels that way in our transactional societies. To me, this work invokes the ethos of the first generation of conceptual artists of the 1960s and 1970s, who often used textual elements as a means of rethinking what art could be, while also being playful in their serious investigations to allow for a certain accessibility by interested art audiences.

“Art is at hand. I just pick it up and ‘play’ with it in the way it allows me to ‘play’ as it already has its potentiality, its language.”

Luisa Cunha, email to Joshua Decter

|

|

|

|

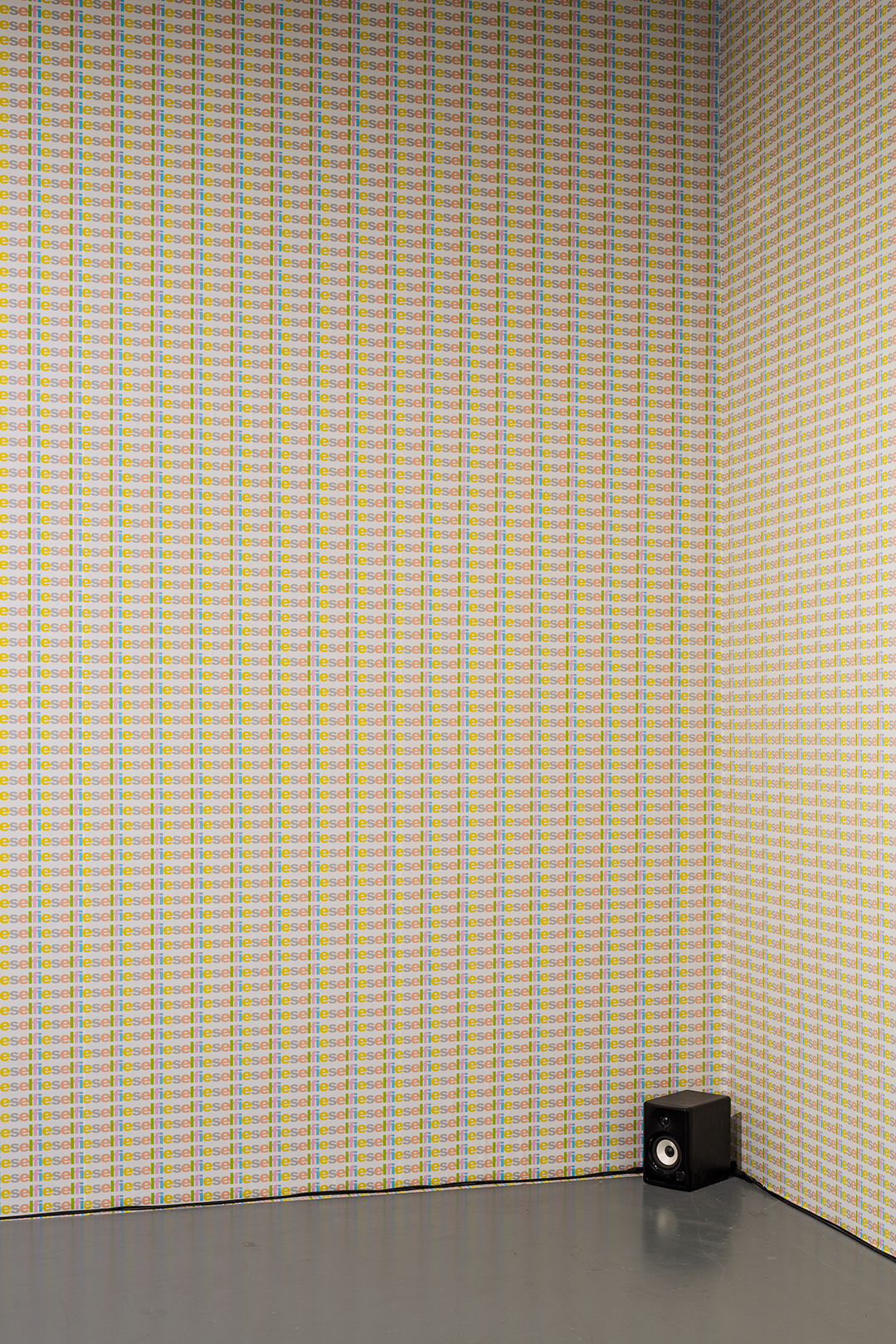

Luisa Cunha, Turn around, 2010. Sound text; 24 s, loop. 4 loudspeakers; dimensions variable. EDP Foundation Art Collection. Luisa Cunha, Selfies #2, 2019. Pigmented print on paper; dimensions variable. Coll. of the artist. Photo: Daniel Malhão, courtesy of the artist and EDP Foundation / MAAT. |

|

A coy sort of self-referentiality also can be detected in the 2019 print entitled Selfies, wherein the artist deploys the word “selfie” in lower-case lettering, endlessly repeating it with no separation between word to the point at which the word nearly dissolves into its constituent letters. This linguistic breakdown is further amplified by the various colours that Cunha has selected for each letter, which are also repeated throughout, producing something approaching an op-art field of pulsating letters. A textualisation of the cultural-social phenomenon of the selfie as an act of self-imaging that tells us everything and nothing about the subject of the selfie. Is this a self-portrait of Cunha by other means? The ultimate post-selfie selfie: a selfie minus the photographic image of the artist. It is also interesting to note that the word “selfie” is a kind of trans-linguistic term that operates globally. The concept and practice of the selfie travels and transmutes across national boundaries; indeed, one might say that there has been a selfie epidemic for many years.

It is a viral term, quite literally. Language is a virus, and everyone is susceptible to catching a selfie, so to speak. One might even say that there has been a selfie pandemic for years, but no vaccine yet. Is Cunha’s Selfies a selfie of selfies: a metaselfie? The ideational condition of the selfie, the subject of which is the selfie itself. We might ask: is every artwork in some sense a selfie of the artist? Cunha gives us the artwork in the age of mass selfie reproduction. How selfieish of her.

For me, this work is emblematic of her ethos as an artist: she made a selfie that is not a selfie and yet became a different kind of selfie. Cunha takes pleasure in questioning art, as well as her status as an artist, and this pleasure is made evident in her work. She seems to leave open the possibility that life – before and beyond art – is ultimately more important than art, even for an artist. Really, finally, what I’m trying to say is that I take Cunha’s art seriously precisely because she does not take art too seriously… which results in her making some very serious art.

|

Joshua Decter’s essay “Luisa Cunha: Make Art Do Nothing Make Art Do Nothing Make Art Do Nothing” was originally published in the book Luisa Cunha. Obras / Works 1992–2022, published by EDP Foundation / MAAT in 2023.

The exhibition Hello! Are You There? (MAAT – Museum of Art, Architecture and Technology, Lisbon, 19/05–28/09/2023), is the most comprehensive retrospective ever of the work by Luisa Cunha (Lisbon, 1949). Spanning multiple media – from video to drawing, painting, and sculpture – a large and wise choice of 52 works occupies the entirety of this floor and extends outside. This exhibition is also the occasion for releasing the most complete catalogue of Luisa Cunha's work to date. With more than 280 pages, the book Luisa Cunha. Obras / Works 1992-2022 encompasses a total of 108 works in dialogue with a selection of text excerpts by various authors, released between 1997 and 2022 in several different publications. The volume also includes two original essays by Isabel Carlos, who curated the exhibition, and by Joshua Decter, an American art historian and critic.

Joshua Decter is an American writer, curator, and art historian living in Lisbon. His books include Art Is a Problem: Selected Criticism, Essays, Interviews and Curatorial Projects (1986-2012) published by JRP|Ringier (2014), and Exhibition as Social Intervention published by Afterall (2014). Decter has contributed to Artforum, Art Review, Mousse, Texte zur Kunst and other periodicals, and has authored numerous exhibition catalogue essays since the 1980s. He has curated exhibitions at PS1 (MoMA PS1), The Museum of Contemporary Art in Chicago, Center for Curatorial Studies Museum at Bard College, the Kunsthalle Vienna, and elsewhere. Since the 1990s, Decter has taught at the University of Applied Arts in Vienna, the School of Visual Arts in NYC, USC in Los Angeles, Cooper Union in NYC, The Center for Curatorial Studies at Bard College, The School of the Art Institute of Chicago, New York University, UCLA, Art Center College of Design, and Bennington College.