Grada Kilomba. O Barco / The Boat

A concise but very insightful documentary on Grada Kilomba’s project, which maat presented in 2021 in the context of BoCA – Biennial of Contemporary Arts.

It’s a sculpture, an installation, a performance, poetry. And I think it is precisely these various disciplines contained in a single piece, that characterise a lot of my work.

Grada Kilomba

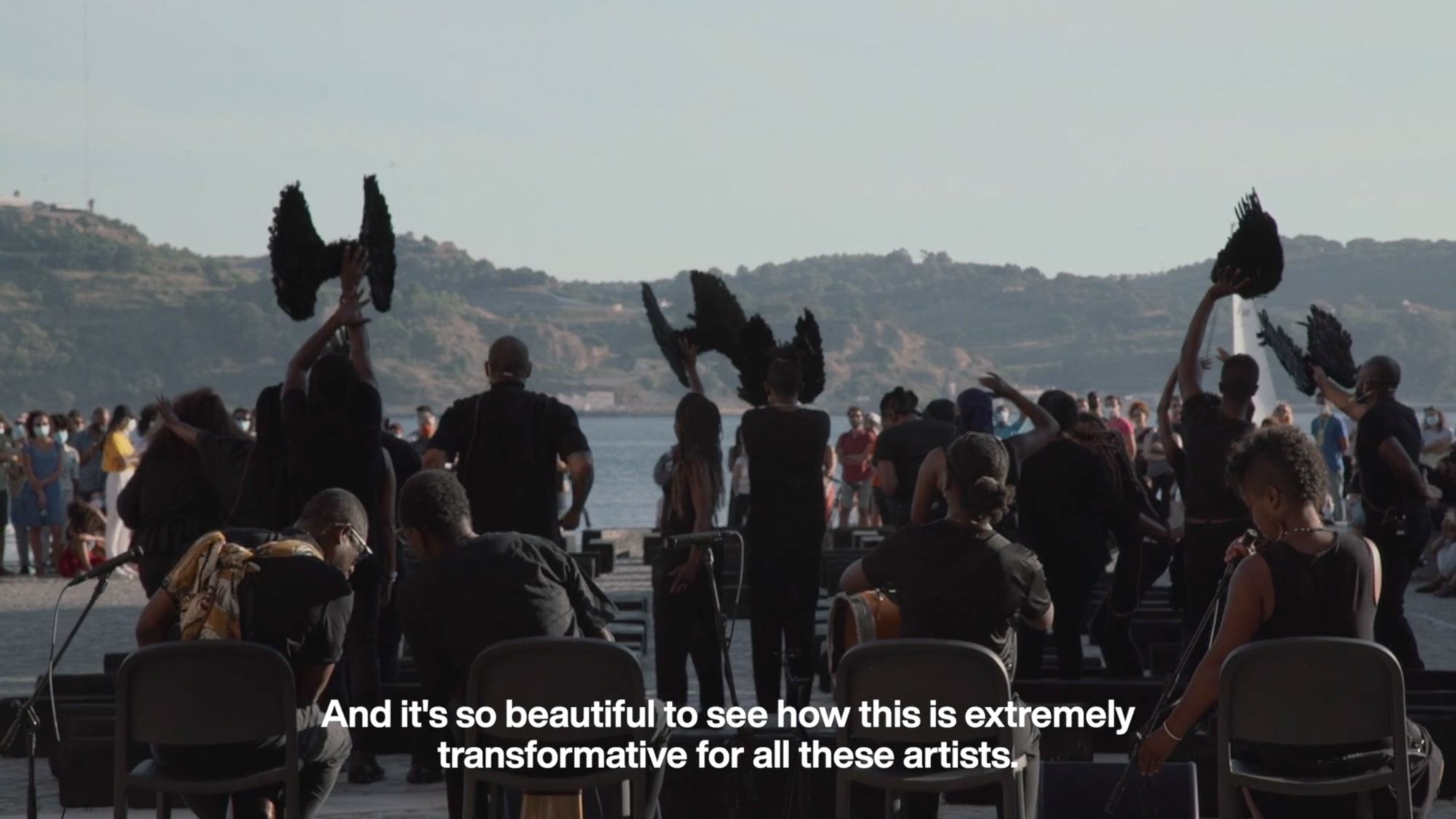

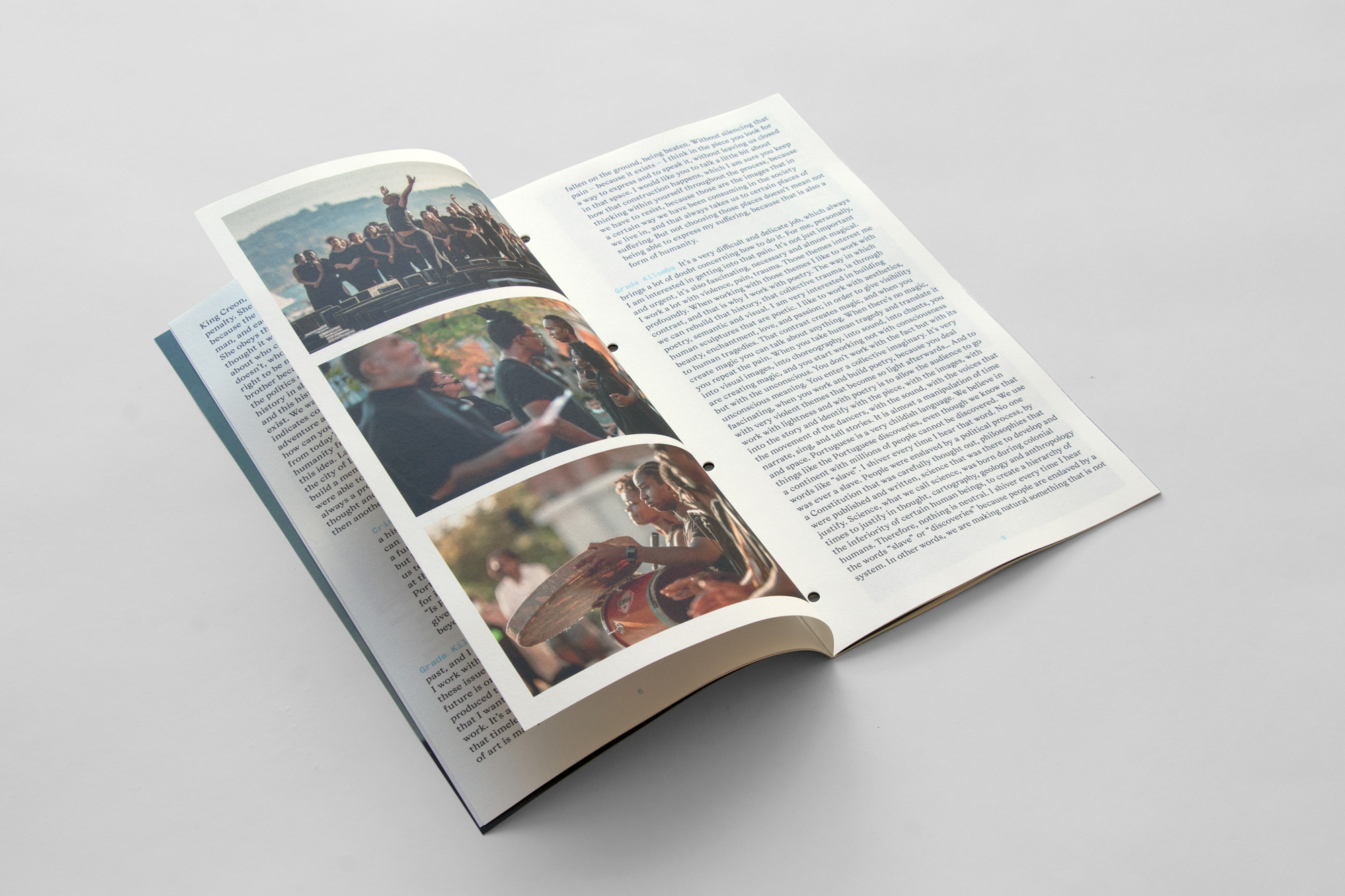

Video stills from the documentary “Grada Kilomba. O Barco / The Boat” (2022). Courtesy of BoCA and Waves of Youth.

Cristina Roldão

I was there for your performance [maat, 03/09/2021], a historical moment in the city of Lisbon, the fact that we can have a piece . . . well, it’s not just a piece, I would say it’s a funeral ceremony. You have spoken a little bit about that, but how does ritualising, or making this ceremony allow us to go forward, allow us to resolve this silenced past, that at the same time is so present and is such a strong part of Portuguese society? Even though we hear over and over, for instance, that racism doesn’t exist, or the old question, “Is Portugal a racist society?”. Why do rituals and ceremonies give space to that? Can it be a step to go beyond the pain, beyond the violence?

Grada Kilomba

Sometimes I get asked why I work with the past, and I respond: I don’t work with the past, I write the future, I work with the creation of the future. Every time we address these issues, we are above all else designing the future. And the future is only created when you produce memory, which is only produced through ceremonies and rituals. It was exactly that that I wanted to work with on this piece, and also generally in my work. It’s almost like building an archaeology, and going within that timelessness. It’s like creating a matrix. The great magic of art is manipulating space and time, to create something that you revisit and that increases plurality, where past, present and future are timeless and coincide. The African diaspora lives in that timelessness. I have a habit of saying that we are futuristic beings, we are Afrofuturists. Every community that is placed in the outskirts, lives in a matrix of timelessness, they live outside the present time. Normative society and the centre live in the past and they aim at all costs to keep, to relive and to re-enact the past. Most marginalised communities and bodies live in the future, because what we reclaim is a futuristic vision, something that in the present is out of step with time. Society can’t deal with or respond to the questions we raise. There is a process to go through and what we reclaim is something that is way beyond the present. To work with all that timelessness is something magical and also fundamental. A ceremony has the capacity of working with the timeless, it can go in that archaeology of looking back, being in the present and designing the future. But above all else, the ceremony and the ritual can do something very magical which is the production of memory. It’s for that reason that most ceremonies and rituals from the diaspora and from every marginalised group became forbidden by law and the Constitution. Capoeira was forbidden with imprisonment until the 1920s. Candomblé was forbidden with imprisonment until the 1930s. Yesterday we were rehearsing with one of the Cape Verdean percussionists, Jair, and he was explaining how dancing and drumming in Cape Verde were forbidden during colonial times by the Portuguese because rituals and ceremonies produce memory. And when you produce memory, you produce identity, and when you produce identity, you project the future. Therefore, one of the policies of Portuguese colonialism and the oppressive regime of European colonialism was the politics of erasing, and they didn’t erase only the names – we can’t access our names – they erased also the ceremonies and the rituals. It was all erased, forbidden by law. It’s not by accident that we are all called Correia, Fernandes and Ferreira. We are called this because African names were forbidden by law. There is a Constitution and laws that were thought out in detail, and built to erase identities. So, rituals and ceremonies are important, and performance can create rituals and ceremonies. In the sculpture people have to crouch down to read the poem in the blocks of burnt wood. There is a ritual, a ceremony, which was designed on purpose, even if people don’t realise. This way, I force people to engage in a ritual, in a choreography of contemplation, even if they are perhaps not aware of it. Through art we create magic, we play with people to go in that unconscious world. Because it is a place to crouch down, a place of mourning, a place for crying, a place for recognising. So during the choreography we played and worked with all these themes.

Video stills from the documentary “Grada Kilomba. O Barco/The Boat” (2022). Courtesy of BoCA and Waves of Youth.

Cristina Roldão

To be talking, to express pain and lament, raises specific challenges because it has been a place, an image and a way to represent us. Black bodies fallen on the ground, being beaten. Without silencing that pain – because it exists – I think in the piece you look for a way to express and to speak it, without leaving us closed in that space. I would like you to talk a little bit about how that construction happens, which I am sure you keep thinking within yourself throughout the process, because we have to resist, because those are the images that in a certain way we have been consuming in the society we live in, and that always takes us to certain places of suffering. But not choosing those places doesn’t mean not being able to express my suffering, because that is also a form of humanity.

Grada Kilomba

It’s a very difficult and delicate job, which always brings a lot of doubt concerning how to do it. For me, personally, I am interested in getting into that pain. It’s not just important and urgent, it’s also fascinating, necessary and almost magical. I work a lot with violence, pain, trauma. Those themes interest me profoundly. When working with those themes I like to work with contrast, and that is why I work with poetry. The way in which we can rebuild that history, that collective trauma, is through poetry, semantic and visual. I am very interested in building human sculptures that are poetic. I like to work with aesthetics, beauty, enchantment, love, and passion; in order to give visibility to human tragedies. That contrast creates magic, and when you create magic you can talk about anything. When there’s no magic, you repeat the pain. When you take human tragedy and translate it into visual images, into choreography, into sound, into chants, you are creating magic, and you start working not with consciousness but with the unconscious. You don’t work with the fact but with its unconscious meaning. You enter a collective imaginary. It’s very fascinating, when you work and build poetry, because you deal with very violent themes that become so light afterwards . . . And to work with lightness and with poetry is to allow the audience to go into the story and identify with the piece, with the images, with the movement of the dancers, with the sound, with the voices that narrate, sing, and tell stories. It is almost a manipulation of time and space. Portuguese is a very childish language. We believe in things like the Portuguese discoveries, even though we know that a continent with millions of people cannot be discovered. We use words like “slave”. I shiver every time I hear that word. No one was ever a slave. People were enslaved by a political process, by a Constitution that was carefully thought out, philosophies that were published and written, science that was there to develop and justify. Science, what we call science, was born during colonial times to justify in thought, cartography, geology and anthropology the inferiority of certain human beings, to create a hierarchy of humans. Therefore, nothing is neutral. I shiver every time I hear the words “slave” or “discoveries” because people are enslaved by a system. In other words, we are making natural something that is not natural. It is a process of violence. This way, we are marking who suffered oppression, we are not questioning who was the oppressor, who wrote the Constitution, the law, who made the system. This is a very comfortable thought we live with. We talk about slave ships, we use such violent terms, of such power… I only realise the violence and power of the terminology we use in Portuguese because in my day to day life I speak German and English, and in those two languages those terms are not used anymore, because they were dismantled and rethought by intellectuals and artists of the African diaspora in Germany, and we have an immense legacy from the United States, from the Black Panthers and a whole movement that gave us a lot of language, and vocabulary. I am interested in deconstructing, creating new images and languages. When we were working on the synopsis, we wrote a lot of emails: “Attention. Forbidden terms: slave, naus [ships], negreiros [concerning the traffic of African people], discoveries”. And then we have a lot more words to think about, like negro and negra that are extremely problematic also. We have the “P” word, that is even more problematic, and we have all these terminologies in Portuguese that are anchored in colonial history. We have a lot of work to do, we have been deconstructing, which is also fascinating.

Excerpts from the public conversation with Grada Kilomba, conducted by Cristina Roldão, held at maat on 4 September 2021.

“Grada Kilomba. O Barco / The Boat”, published in Portuguese and English languages by maat / EDP Foundation in 2021, includes the entire conversation with the artist. Photos: Lisa Hartje Moura.

Grada Kilomba is a Portuguese artist based in Berlin, whose work draws on memory, trauma, violence, and the post-colonial condition. Best known for her subversive writing and poetic imagery, Kilomba published Plantation Memories: Episodes of Everyday Racism in 2008. Reprinted in multiple editions and translated to different languages, the book examines, via a psychoanalytic lens, the methods used to dehumanise and oppress Black people throughout history.

In her multimedia installations, Kilomba creates a critical and immersive space of storytelling, to explore what she calls the “colonial wound”, using performance, choreography, staged reading, theatre, video, photography and installation. Her work has been presented in major international venues such as Lubumbashi Biennale (2019), Berlin Biennale (2018); Documenta (Kassel, 2017), São Paulo Biennale (2016), among many other. Heroines, Birds and Monsters is her first solo exhibition in the United States, at the Amant Foundation, Brooklyn.

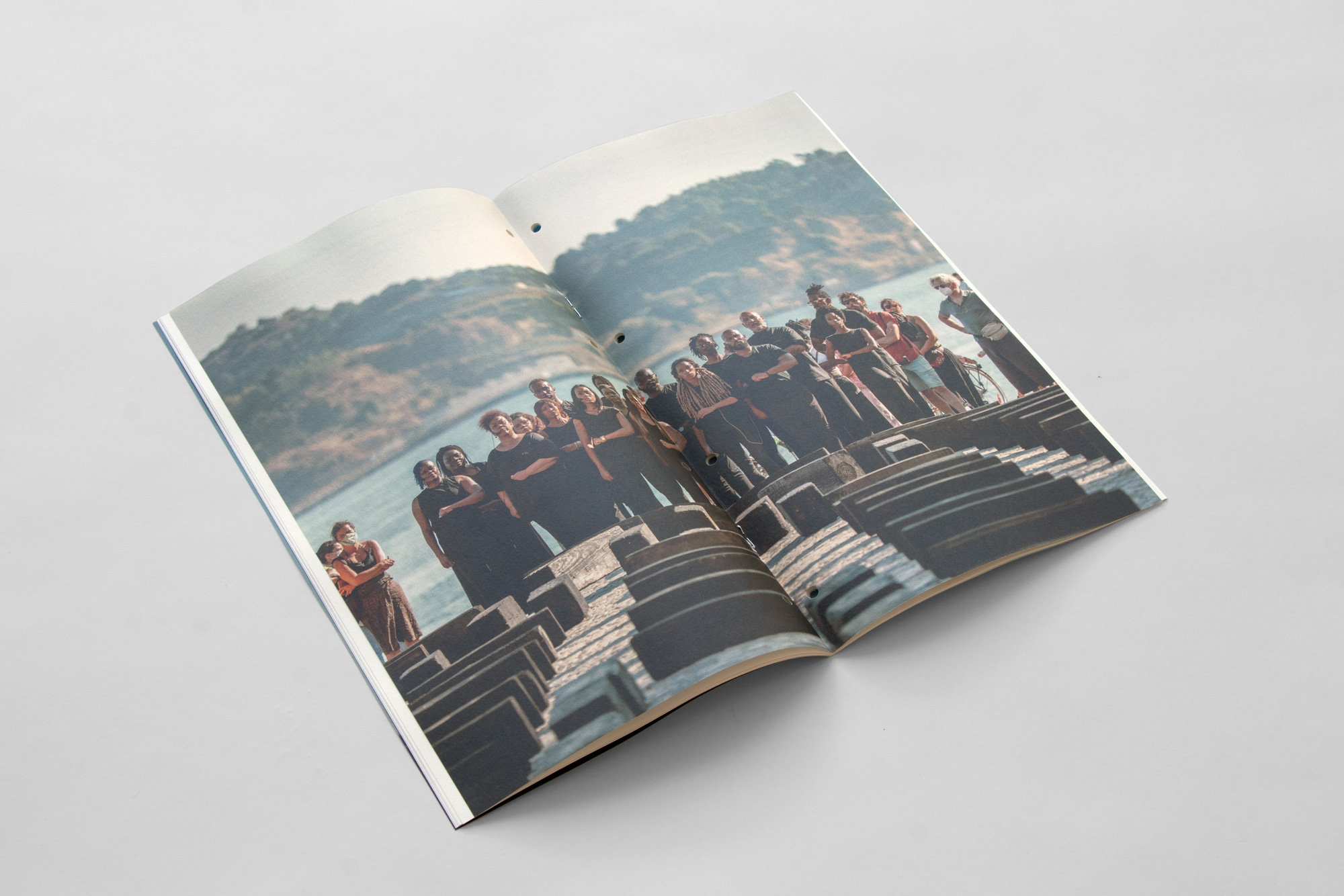

O Barco/The Boat is Grada Kilomba’s first large-scale installation. Stretching 32 meters along the Tagus river, it invites the audience to enter a garden of memory in which a poem, translated into various languages – from Yoruba and Kimbundu to Creole and Setswana, as well as Portuguese, English and Arabic – rests on burnt wooden blocks, recalling forgotten stories and identities. In the Western imaginary, a ship is easily associated with glory, freedom, and maritime expansion, described as “discoveries” but Kilomba’s boat carefully draws the space created to accommodate the bodies of millions of Africans, enslaved by European empires. A performance in three acts, in which several generations of Afro-descendant communities are the central interpreters, turns the O Barco/The Boat into a place of acknowledgement, a garden of memory, but also a viewpoint to the future.

This project is commissioned and co-produced by BoCA , maat and Kunsthalle Baden-Baden, in partnership with Câmara Municipal de Lisboa/EGEAC within the programme Lisboa na Rua'21. The production is support by ArtWorks .