Welket Bungué, video still from “Metalheart” (“Carbono” triptych), 2019.

Courtesy of the artist.

Welket Bungué: Metalheart

A body full of the marks of the past heals its past hurts and hides living losses. Here beats a heart made invulnerable by noise, iron, and twist. Our boundaries are today tighter than ever. Who are the confined ones, who decide those who can and cannot enter?! Shall we deal with the migration as if it is a dead body poisoning our meekness, or is it a real question that imperial western capitalism doesn’t want to answer? The question is: are you willing to stand and confront this (un)ethical premise?

— Welket Bungué

Shown here from 13 November 2020 to 18 January 2021.

EVERY LAND HAS A NAME, AND WE NEED TO TELL THE WORLD

An interview with Welket Bungué by Marta Lança

During my stay in Cape Verde, I realised it was a very photogenic place and one that was easy to romanticise, so I picked up my camera and filmed. I shot three films that compose a triptych focused on landscapes, on visible contrasts in resources and urban (dis)order, and ultimately on several subthemes I like to think about when I'm in these spontaneous processes of shooting while traveling. Hito Steyerl’s exodic cinema is not only an aesthetic but also a methodology that influences performative and technical decisions I made while shooting and creating meaning within the images in these three films: Kau Berdi, Ex Explorador Exproriador, and Metalheart. I call this triptych Carbono, an homage to this ethereal chemical element, which has increased in the atmosphere to the point that it conditions our life on Earth, not only as living beings but also as creatures of habit.

— Welket Bungué

-

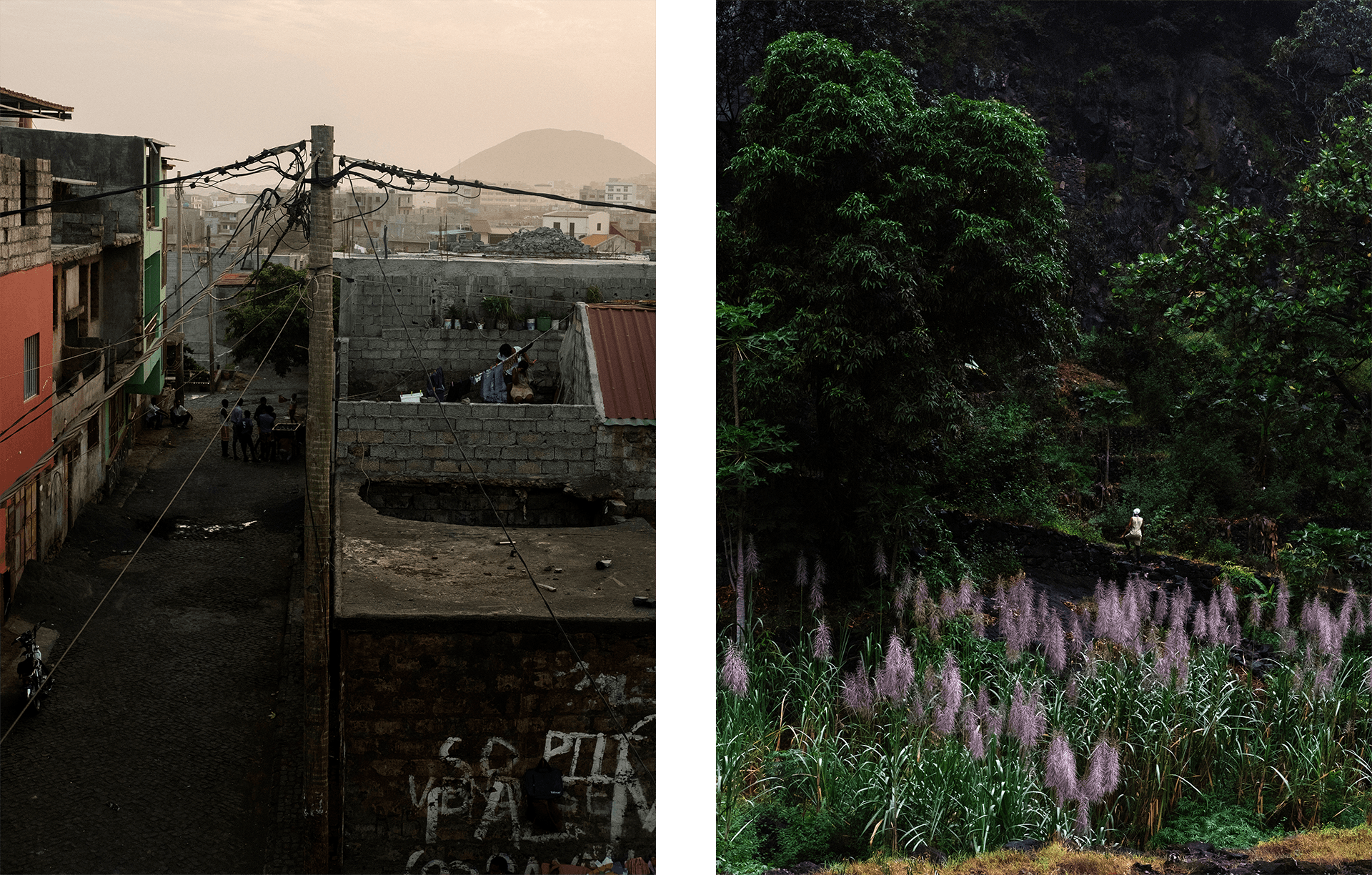

Bairro Eugénio Lima, Cidade da Praia. Photo: Kristin Bethge, Santiago island, Cape Verde 2019.

-

A local community cornfield in Vale do Paúl. Photo: Kristin Bethge, Santo Antão Island, Cape Verde 2019.

Marta Lança

How did the triptych Carbono [Carbon] come about?

Welket Bungué

It was born out of a desire to film on African soil. I had the same feeling when I was in Guinea-Bissau between May and June of 2019.

Marta Lança

There is an essay-like quality to your films that feeds off spontaneity and performativity. Ideas emerge through an interesting traveling gaze that sows meanings together.

Welket Bungué

As a performer, my style of filming depends a lot on my perception of the space and its constraints through the mechanical filter of the movie camera. Because of that, it is necessary to recreate a (non-)narrative line after the images are shot, as the immanent meanings of my political and humanistic conception of the world and its organic quality determine the themes highlighted in the film when the editing stage begins. The three films are particular to the different places where I shot the images: in Mindelo, in the tourist area between Praia and Tarrafal, including Assomada, and the Eugénio Lima and Praia Quebra Canela neighbourhoods (in Praia, São Vicente Island).

Marta Lança

In what sense is Cape Verde easy to romanticise?

Welket Bungué

Because from a cultural and native point of view it is mainly a fluctuating culture. Imagine if they were “Atlantic” and not African, or vice-versa. What does that mean? Or rather what else could you want to be beyond one of these two definitions? On the one hand, they avoid the colonial inheritance, in the sense of history seen through the West’s eyes, but on the other hand – once you are considered “Atlantic” – you self-define as “galactic” or territorially emancipated from continental African history. For all this sprinkling of possibilities, it is worth going to Cape Verde to film its people and imposing landscape. They expose this lack of definition that both liberates, but doesn’t crystallise culture or identity in an autochthonous way.

-

Welket Bungué, video still from “Kau Berdi” (“Carbono” triptych), 2019.

-

Welket Bungué, video still from “Ex Explorador Expropriador”, (“Carbono” triptych), 2019.

-

Welket Bungué, video still from “Metalheart” (“Carbono” triptych), 2019.

Marta Lança

Why Carbono as the title of this trilogy?

Welket Bungué

The title pays homage to the ethereal chemical element, CO2, which has increased in the atmosphere to the point that it conditions our life on Earth, not only as living beings but also as creatures of habit. It is also an attempt to make us think about the effects caused by the excessive amount of this matter, i.e., carbon, in the air, and also how we associate it with predatory capitalism that, directly or indirectly, affects the landscape of territories that gradually and indistinctly reveal the abysmal differences stratifying society at a global level.

Marta Lança

How do you see the connection between Kau Berdi, Ex Explorador Exproriador and Metalheart?

Welket Bungué

I see them as short experimental documentaries that compose a triptych focused on landscapes and on contrasts.

Marta Lança

Which contrasts did you want to highlight in these films?

Welket Bungué

The visible contrasts in terms of resources and urban (dis)order and, ultimately, the several subthemes I like to reflect upon when I'm in these spontaneous processes of shooting while traveling.

Marta Lança

Which filmmakers inspire you?

Welket Bungué

In this case, Hito Steyerl’s exodic cinema, which is not only an aesthetic but also a methodology that influences the performative and technical decisions I made while filming and creating meaning within the images in these three films.

Marta Lança

Kau Berdi has a poetic inscription: “Every land has a name, and we need to tell the world”. How can visual poetry translate this?

Welket Bungué

The visual poetry of this essay-film yearns to recall an image by mapping a pre-colonial land, not just Cape Verde but all of Africa, and the green, rich, and colossal landscapes that show the richness and vitality that only Africa in all its natural innocuousness contains. The title Kau Berdi comes from the Creole and means “Green Land”.

Marta Lança

At the same time, it dispenses with words.

Welket Bungué

I’d like to dispense with words but “African (wo)man’s cinema” imposes the necessity of instilling messages with a literary sense, whether visual or apparently narrative, to ensure that in the post-contemporary world there is a place for potential interest in critical, academic, literary, and political research tied to the viewing of films (artworks). I say this because if images are powerful for identifying and revolutionising through the multiple interpretations they introduce into human feelings, then words identify through questioning, as they are connected to an idea of language as domination and authority – in other words, only those with social and political legitimacy write and speak. That is why I have to write, inscribing words as a poetic element by the shape they take rather than by their meaning. I believe more in allowing the film to communicate fully than in my poetic and literary proposition of overlapping or complementing the image. My aim is that the place, time, and people filmed do not disappear or are erased, saving them from what happened in many of the places I visited and show in the film Kau Berdi.

-

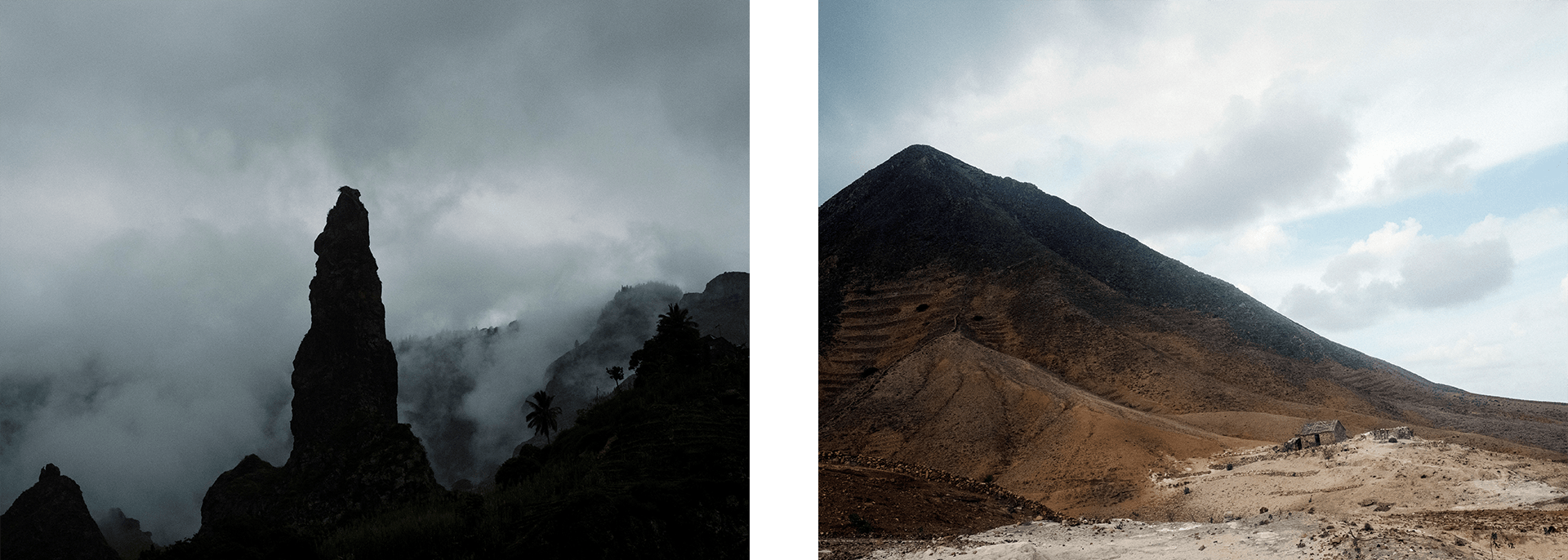

Delgadim, Vale de Ribeira Grande. Photo: Kristin Bethge, Santo Antão island, Cape Verde, 2019.

-

Abandoned house, seen from the road between Porto Novo and Janela. Photo: Kristin Bethge, Santo Antão island, Cape Verde, 2019.

Marta Lança

How do you see the historical and symbolic relationships between Cape Verde and Guinea-Bissau since their fight for independence?

Welket Bungué

That joint struggle was against the forces of colonial domination in both countries, i.e., Portuguese colonisation. The fight for liberation united both peoples ideologically and culturally. However, in my view, it was not completely successful in its genuine desire to consolidate the “union” of the two states-countries in a political and joint development sense. It failed to match the intensity with which the desire for liberation had inspired a combative and fraternal attitude aimed at an idea of presenting a bilateral but sovereign communion to Africa and the western world. Today, these relations should be taken care of primarily by the peoples themselves, and especially between territories, and also from an international scope - the politics of cooperation have to be revised and dignified, and with greater equity with regard to their current needs.

Marta Lança

What did you feel and what did you want to say by visiting the Amílcar Cabral House in Achada Falcão?

Welket Bungué

It was necessary to be specific in order to attribute value to an archive named after this paramount figure in the pan-African uprising, within the ideological disagreements that led to the liberation of Guinea-Bissau and Cape Verde. But also, to assess the state of the legacy of the symbolic leaders of African culture, whose memory in many cases should be reappraised and better cared for.

Marta Lança

In the synopsis for Metalheart you ask: “Who are the confined? Who decides who enters and takes part and who doesn’t?” How do you see confinement in certain areas of the world?

Welket Bungué

There are several ways to understand confinement and they depend on the perception of those who are living it or those who are imposing it. In the case of Metalheart, which should premiere this year in Belgium at the 24th AFRIKA Filmfestival, the confinement I talk about is symbolically related to the frontiers we, western countries/people, impose on certain groups/communities, and at the same time how we behave as the privileged people that we are. We benefit from the right and legitimacy/authority to travel and move in most countries outside Europe without even considering that we might be contributing to the cultural alienation of those countries/territories.

Marta Lança

How does the boat’s scrapyard metaphor work?

Welket Bungué

The film shows the “burial” of an enormous sheet of metal, the remains of a boat abandoned on a beach reached by a pier, which connects to a scrapyard walled off by other pieces of metal. We watch an excavator drag this “drowned/sunken” metal structure from the water to the iron cemetery, and we see people watching on land. I associated this action to the arrival of the boats loaded with asylum seekers that can be seen every day in their dozens along the coast of Europe.

Marta Lança

Tell us about your production company, Kussa.

Welket Bungué

Kussa is freedom, life, and movement. My brother Welsau is based in Paris, and I presently live in Berlin. Whenever we travel, we always seek out elements that can create a new story, so we establish new and interesting collaborations with locals or with artists, mostly musicians, that we already regularly work with.

Originally published in Portuguese on BUALA, under a Creative Commons license.

Translation by Susana Pomba.

All images courtesy of Welket Bungué and Kussa Productions.

Welket Bungué, originally from the Balanta tribe, was born in Xitole (Guinea-Bissau). A Portuguese-Guinean actor and film director, currently based in Berlin, in 2020, he starred as Franz Biberkopf in Berlin Alexanderplatz, directed by Burhan Qurbani, which earned him a nomination for Berlinale’s Silver Bear. He’s also founder of Kussa Productions.

In 2020, the Fuso Festival, held at maat in August, awarded "Metalheart" (2019). The jury highlighted the “markedly raw poetic quality”, strongly touching the edition’s theme, “Diversity. Adversity". The award resulted in the acquisition of the work by the EDP Foundation.