Sonia Levy: For the Love of Corals

Shown here at maat ext. Cinema from 9 July to 9 September 2021.

For the Love of Corals — shown here as part of the public programme Architecture of the Enclosed Sea. Between Aquaria and Marine Protected Areas, curated by Louise Carver and co-developed by the TBA21–Academy and maat in the context of the exhibition Aquaria – Or the Illusion of a Boxed Sea — is a cinematic inquiry and artist film developed over the course of a year, filming the daily labor of the team caring for these endangered beings, the relentless attempt to resuscitate corals from anthropogenic extinction. The film follows the life cycle of the marine invertebrates in their laboratory tanks, replicating the seasonality and moon phase of an Australian reef in the basement of the Horniman Museum.

“For the Love of Corals”, 2018

Written, produced and directed by Sonia Levy

Edited by Sonia Levy and Sam Smith

Soundtrack and located sound by Jez Riley French

Music by Georgia Rodgers

“Distal Theories”, performed by Two New Duo: Ellen Fallowfield (cello) and Stephen Menotti (trombone), Partial Filter, performed by David Powell (tuba)

Coral egg and embryo development time lapses by Jamie Craggs and Sonia Levy

Special thanks to Jamie Craggs; Project Coral: Michelle Davies, Chloé Priestland, Keri O’Neil; and The Horniman Museum and Gardens: Alison McKay and Connie Churcher, Emma Nicholls and Jo Hatton, Henry Rowsell; Filip Tydén, Nella Aarne and Sam Smith, Jez Riley French, Alexandra Arènes and Soheil Hajmirbaba, Anna Ricciardi and Ayesha Keshani

Produced with the support of Obsidian Coast and Fluxus Art Projects

Image: video still from “For the Love of Corals” (2018) by Sonia Levy. Courtesy of the artist.

For the Love of Corals

Life in the Ruins of the Museum1

Sonia Levy

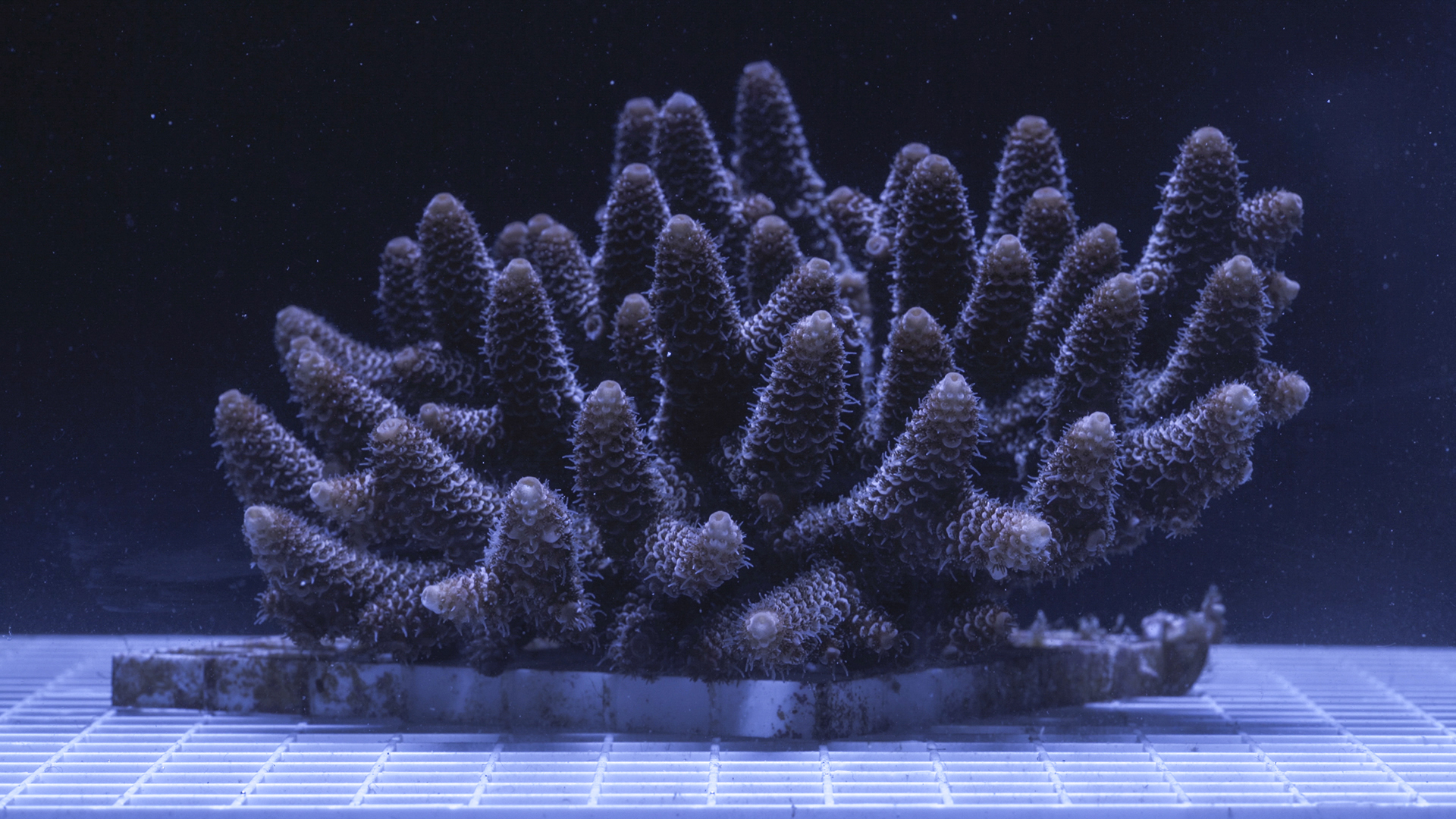

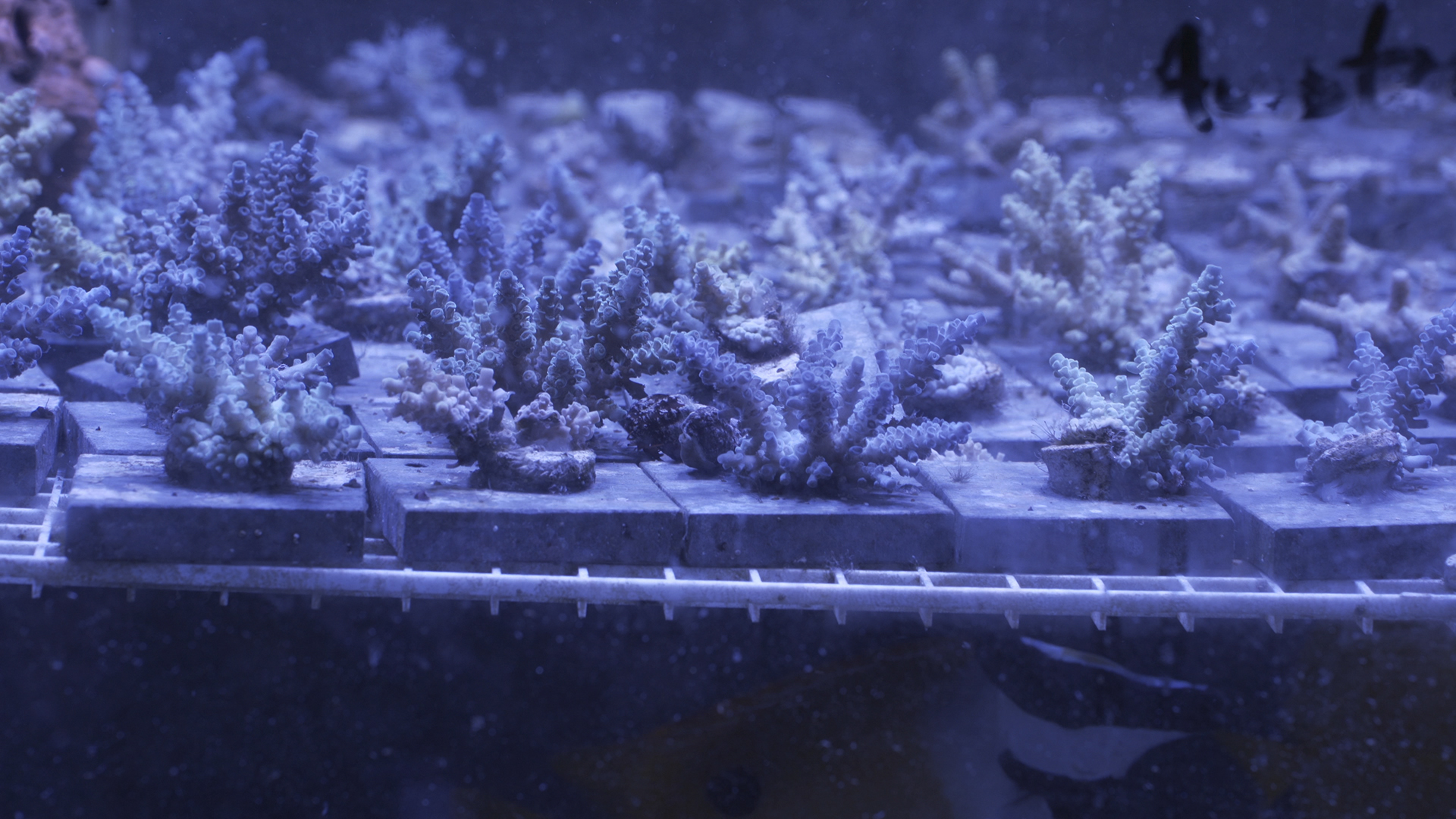

Behind-the-scenes, in the basement of the Horniman Museum and Gardens in London, a team of marine biologists and aquarists led by Jamie Craggs have initiated Project Coral, a leading endeavor to breed corals ex situ in specially designed tanks. By mirroring the climatic conditions – seasonal temperature changes, solar irradiance and, last but not least, lunar cycles – of the Great Barrier Reef within custom-built mesocosms, the team has become the first in the world to induce corals to spawn in a laboratory. Research is also underway to elaborate methods to increase the survivorship of juvenile corals during their delicate embryonic and larval stage, before their metamorphosis into reef builders.

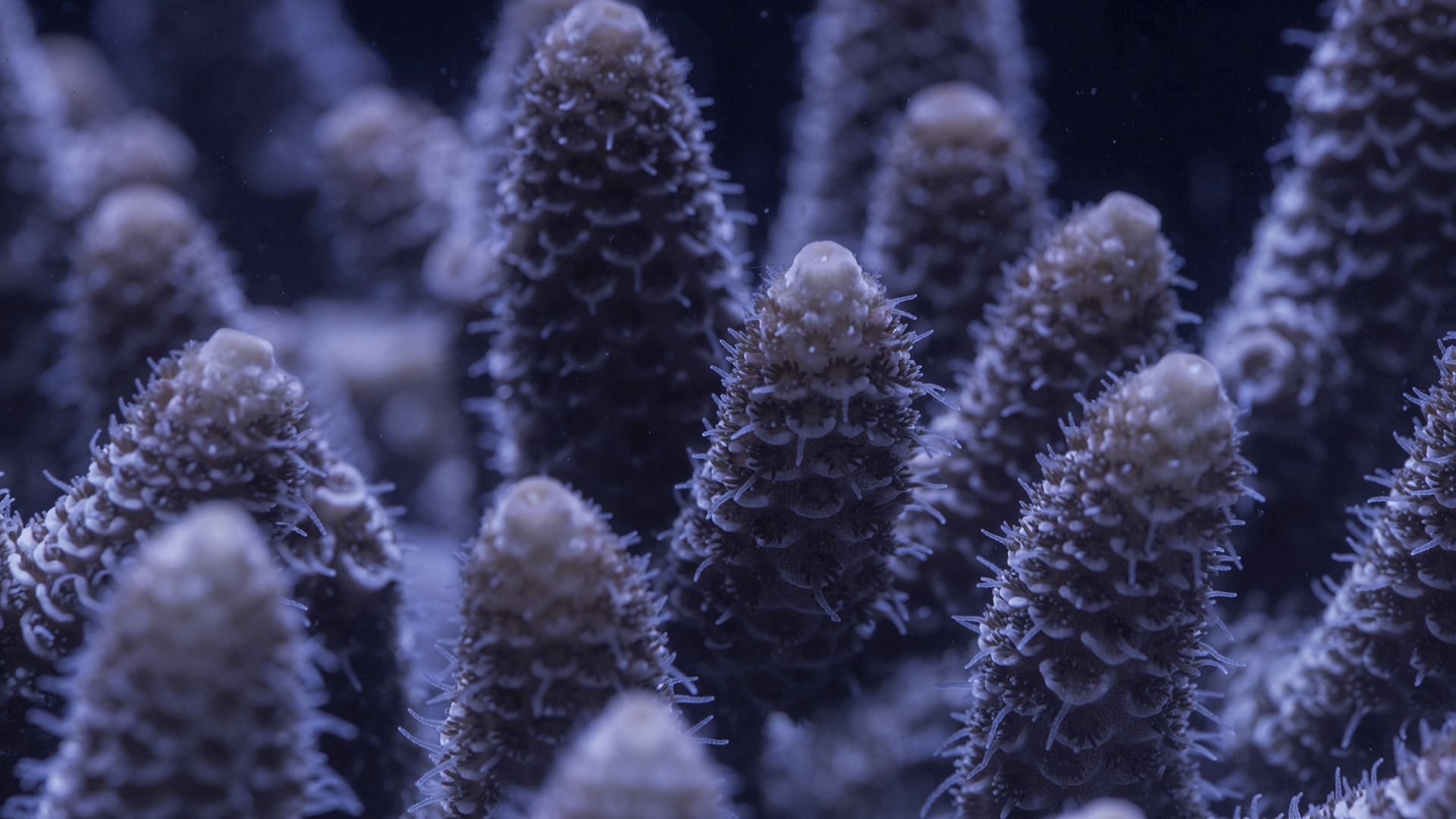

I began filming at the Horniman Museum in late 2017, viewing this coral restoration project as a case study of new paradigms for multispecies living, environmental conservation, and natural history that are emerging in the wake of the “New Climatic Regime.” (→ 2) Corals are “canaries in the coal mine,” their bleaching and demise markers of the devastating effects of climate change. Project Coral is an acknowledgment of the precarity of coral reef assemblages in a warming ocean, an affirmation of life forms’ entanglements in this new climatic epoch from which humans can no longer extract themselves. But the project is equally a rediscovery of the sensitivities of our planet and its more-than-human inhabitants. Corals are intricate multispecies and multiscale ecological units. They demonstrate how life forms are not separated from their environment but, on the contrary, by their sheer existence make and constitute environments for themselves and others, contributing to adjacent ecosystems with complex and far-reaching effects. Project Coral expands that assemblage to include scientists, aquarists, and a range of other human and nonhuman actants. For the Love of Corals is a cinematic inquiry and artist film developed over the course of a year, filming the daily labor of the team caring for these endangered beings, the relentless attempt to resuscitate corals from anthropogenic extinction. The film follows the life cycle of the marine invertebrates in their laboratory tanks, replicating the seasonality and moon phase of an Australian reef in the basement of the Horniman Museum. This short essay will discuss some of the research that has informed this film project.

-

(1) The author would like to thank Jamie Craggs, the Project Coral team, and the Horniman Museum and Gardens for their support. For the Love of Corals was produced with the support of Obsidian Coast and Fluxus Art Projects.

-

(2) See Bruno Latour, Facing Gaia: Eight Lectures on the New Climatic Regime, trans. Catherine Porter (Cambridge: Polity Press, 2017). Originally published in French as Face à Gaïa. Huit conférences sur le nouveau régime climatique (Paris, 2015).

a.

b.

c.

d.

e.

f.

Video stills from "For the Love of Corals", 2018, by Sonia Levy. With kind permission of the Horniman Museum and Gardens.

a. Lab grown corals from the genus Acropora, born and bred at the Horniman Museum.

b. Details of a lab coral from the species Acropora millepora.

c. Project Coral basement laboratory, behind-the-scenes at the Horniman Museum.

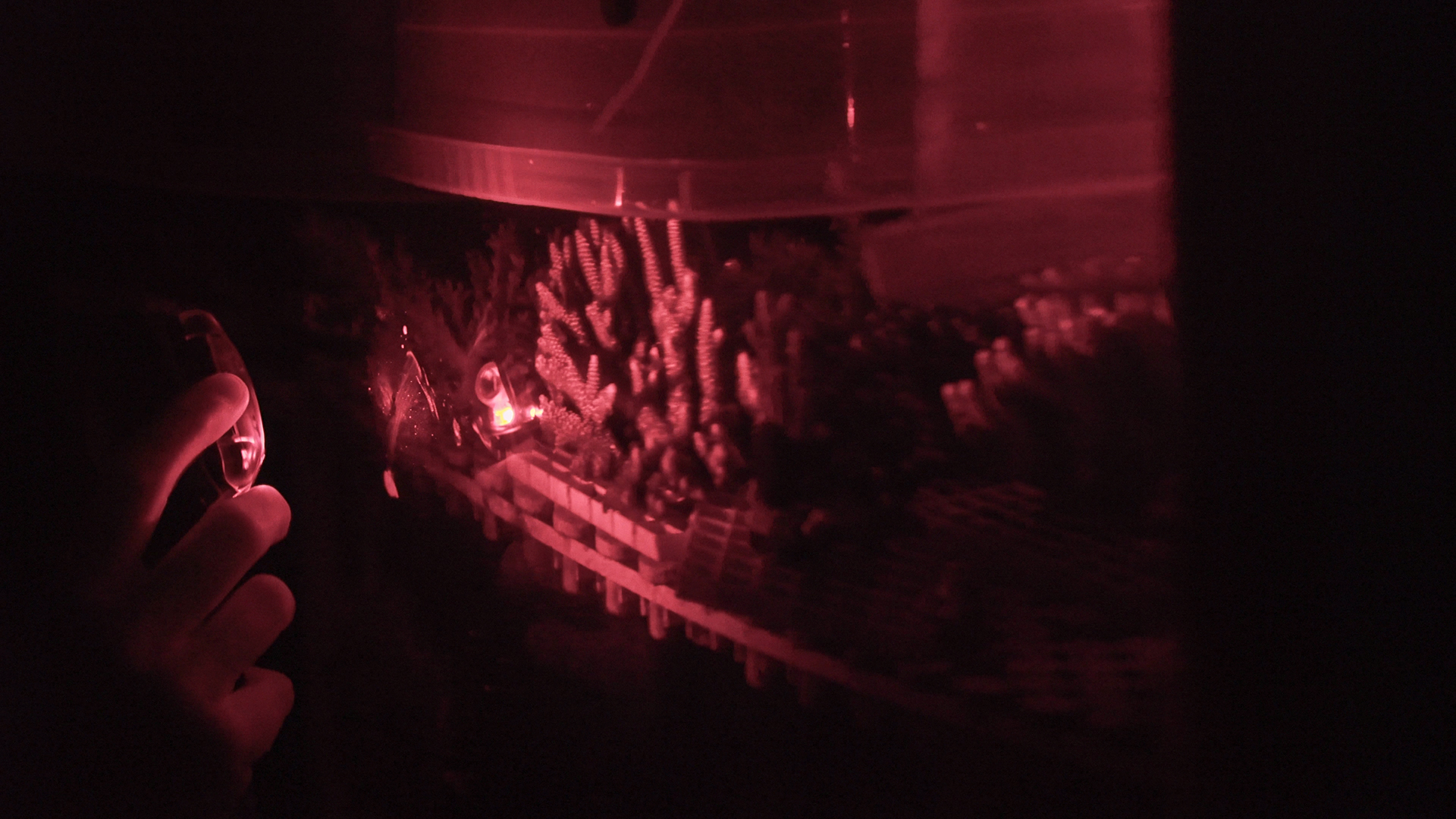

d. Project Coral team inspecting corals under red light around spawning-time.

e. Project Coral team collecting eggs.

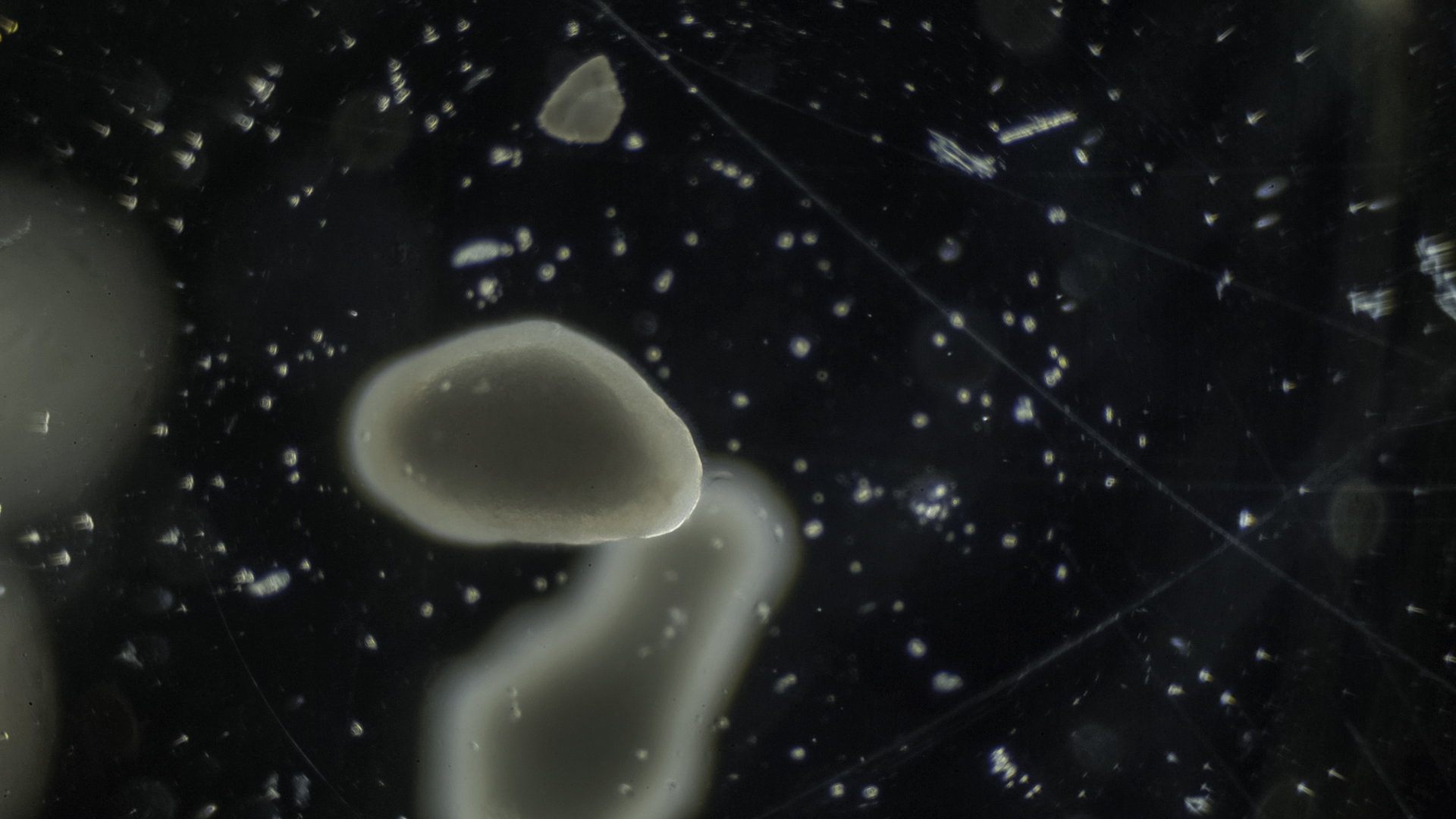

f. Corals’ embryogenesis stages.

I. Corals as Subversive Figures in the Natural Order

The Horniman Museum and Gardens is an anthropology and natural history museum in South London, which also has an aquarium in its basement. Tea trader Frederick John Horniman, founder of the Museum, turned his extensive private collection into a public display in 1901, in a gesture to “bring the world to Forest Hill.” (→ 3)

Public museums were part of the Western modernist project, and their collections gathered by the expansion of empires. Specimens collected from far and wide were placed “inside” the ordered and categorized space of the museum, promoting a modern scientific view of the world. Natural history museums are displays of the classifying and ordering impulse in search of the universal laws of “nature” that animated the early days of modern science. Embedded within the Horniman’s Victorian-era natural history collection, “nature” is presented as a domain of mute materialities governed by mechanistic principles. The systematic exhibits of the Natural History Gallery present species as extracted from their environment, obfuscating the vital codependency existing between life forms. By contrast, the work of Project Coral makes palpable the tangled web of humans, nonhuman life forms, and technologies that the corals depend on for their survival.

Corals demonstrate how life forms terraform; they alter their environment, making it a place capable of supporting life.

As a model for the concept of “holobiont,” (→ 4) corals are tangible world-makers – from their symbiotic relation with an alga dwelling inside their flesh, to their skeleton, built from bodily secretions, which creates shelters from which whole ecosystems emerge, affecting the productivity of the part of the ocean in which they settle. Coral reefs are “oases” in otherwise barren seascapes, and we all depend directly or indirectly on the health of these holobionts. Their disappearance prefigures hunger and the collapse of the fisheries of many ocean-bordering communities. Moreover, we are just beginning to fathom how this drastic reduction in life might affect ocean chemistry and biogeochemical cycles of the Earth system.

Corals demonstrate how life forms terraform; they alter their environment, making it a place capable of supporting life. They disrupt the canonized animal, vegetal, and mineral categories of natural history. They subvert the notion of individuality to convey this complex notion that life forms are always already entangled, enfolded into each other at a local scale whilst affecting global processes. The environment is not imposed upon life forms but, on the contrary, life forms make the various components of and for their own environment. (→ 5)

I am interested to see how this figure of the coral and the urgent restoration projects being done to try and counteract their extinction might play out in redefining our ways of relating to and understanding “nature” – a necessary shift from perceiving it as a separated domain, to an understanding of the necessity of the enmeshment of life forms, from which humans can’t extract themselves anymore.

-

(3) Retrieved from the website of the Horniman Museum and Gardens.

-

(4) Lynn Margulis coined the term “holobiont,” see Lynn Margulis and René Fester (eds.), Symbiosis as a Source of Evolutionary Innovation: Speciation and Morphogenesis (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1991).

- (5) See Bruno Latour and Timothy M. Lenton, “Extending the Domain of Freedom, or Why Gaia Is So Hard to Understand,” Critical Inquiry 45, no. 3 (2019): 659–80.

g.

h.

g. Coral larvae in their free-swimming stage 24 hours after IVF procedure at the Horniman Museum.

h. One-year old coral born at the Horniman Museum.

II. Scientific Caring6 in the Ruins7

In a strange turn of events, the colonial urge to gather knowledge during the Enlightenment period, the thirst for and collection of millions of specimens, which filled and built the natural history museums, zoological gardens, and aquariums, has resulted in repositories representative of past and ongoing capitalism-induced extinctions. Natural history museums and collections stand as testimonies of the invention of the colonial Western notions of human exceptionalism, the ways in which certain bodies and territories were turned into resources, but have paradoxically become a tribute to the abundance and variation of life forms that once populated the planet before this new climatic era.

I wanted to examine how this Architectural context of a museum, which still echoes Enlightenment values of Man mastery over nature, might become a base for a project with the potential to exemplify a collaborative multispecies survival endeavor. Whilst the corals remain in captivity as part of the Horniman’s “Living” Collection, the shared attempt to save them establishes a new and generative assemblage of life-affirming care.

Acknowledgment of the damage caused to coral reefs is embodied in the work of the team at Project Coral – from the precision involved in Coral-IVF (in vitro fertilization) and the protocols of raising corals from their embryonic stage to the level of constant supervision that the project’s success requires. There is a crossover between the professional detached space of the scientific lab and the intimacy and responsibility of caring for a living being. The role of the team is shaped by the custodianship of museum conservation and the epistemologies of the scientific method, but the scientists and the corals have also become involved in each other’s life. This proximity to and involvement with the corals is the sharing of territorial space, both the familiar working space but in a cosmopolitical (→ 8) sense, too, in that it recognizes earthly commons. The scientists and the corals are entangled in sharing a space for working, living, and world-making, expanding the range of possible worlds in common. (→ 9) In the museum, an ordering impulse has been replaced with a world-making one, and a network of humans, nonhumans, life forms, and technologies coalesce to form this critical practice of care.

-

(6) See Donna Haraway, “Making Oddkin: Story Telling for Earthly Survival” (lecture, Yale University, New Haven, CT, October 23, 2017), available here (accessed July 2021).

-

(7) In The Mushroom at the End of the World, anthropologist Anna Tsing urges us to look at what emerges in the ruins of capitalism. She invites us to examine closely the particular types of assemblages of disturbed human and nonhuman life, which arise from the politics of extractivism. See Anna Tsing, The Mushroom at the End of the World: On the Possibility of Life in Capitalist Ruins (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2015), see esp. 20.

-

(8) See Isabelle Stengers, Cosmopolitics I, trans. Robert Bononno (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2010); Cosmopolitics II, trans. Robert Bononno (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2011). Originally published in French as Cosmopolitiques I and Cosmopolitiques II (Paris: La Découverte, 2003).

-

(9) See Albena Yaneva, “Introduction: What Is Cosmopolitical Design?,” in What Is Cosmopolitical Design? Design, Nature and the Built Environment (ed.) Albena Yaneva and Alejandro Zaera-Polo (London: Routledge, 2015), 1–20.

Display cases at the Horniman Natural History Gallery.

III. Documenting and Practicing Entanglements in the New Climatic Regime

What is the role of filmmaking in this “new climatic era”?

The tidal pull of the moon is strong, considering how it permeates life forms. Yearly mass spawning of corals is prompted by the light of full moons, simultaneously uniting hundreds of different species at night across the ocean. Moonlight, especially that of the full moon, is symbolic of transformative power. Stories and myths involving moon phases are told as ways to see through darkness, in the absence of the illumination of knowledge — or perhaps as a different kind of knowledge. Indeed, as the objective, stable background for knowledge that “nature” once represented is now gone, philosopher of science Isabelle Stengers points out that the question “what do we know?” has been transformed into the question “what can we know?” (→ 10)

It’s November 2017, the day of the full moon and I am invited to join Project Coral for the yearly spawning. Outside, it’s a shivery November day in London, inside I am projected into the tropical climate of the lab, its wetness and briny smell. A pervasive white noise is permeating the atmosphere as apparatuses are plugged in everywhere and water is pumped, the instruments sustaining this coral intensive care unit. For spawning to occur during the daytime in the United Kingdom, cycles of the laboratory tanks at Project Coral are kept in such a way that their night is our day. Jamie tells me the corals are particularly sensitive to disturbance with sunlight around spawning time since it could upset the eggs’ release. Corals having evolved to spawn under the cover of night to avoid daylight predators. Therefore, the team is equipped with red-light headlamps, as they go in and out of a tarpaulin tent set up in front of the tanks. I feel a sense of trepidation at frst when I’m given a red headlamp and step inside. I follow Jamie as he is rapidly shining his headlamp over floating containers. That is where the eggs will be collected and attributed to the right individual. Inspecting the corals up close, Jamie expresses that they are near to spawning. He is looking for the pink bulge of the eggs as they appear in the corals’ mouths, a visual cue indicating the colony impending spawn.

Later that day, the corals start releasing their eggs and I can just about film the team prudently picking the pinhead-sized bundles, illuminated by the ominous red of their headlamps.

What is the role of filmmaking in this “new climatic era”? And what are the representational challenges involved in such a paradigm shift? The fable of “nature” as a separate domain has collapsed. Nature can no longer be represented “out there,” as a spectacle to be looked at from afar. As artists, shouldn’t our task become one of bearing witness to this critical chain of interdependence brought about by this globalized state of precarity?

Previously published in: Bruno Latour and Peter Weibel (ed.), Critical Zones. The Science and Politics of Landing on Earth (Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press, 2020), 32–35.

-

(10) Isabelle Stengers, “Including Nonhumans in Political Theory: Opening Pandora’s Box?,” in Political Matter: Technoscience, Democracy, and Public Life, ed. Bruce Braun and Sarah J. Whatmore (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2010), 3–34.

Sonia Levy is an artist and filmmaker, currently based in London. Her practice engages contemporary socio-ecological urgencies at the intersection of art and science. Through this co-becoming of disciplines, she uses filmmaking to query science’s history of entanglement with western colonial extractivist logics. Her work attempts to develop new practices of care, fostering dialogue as a means to consider new worlds. She was the 2021 commissioned artist at Radar Loughborough and Aarhus University's Ecological Globalisation Research Group. She has exhibited in the UK and internationally including shows and screenings at Centre Pompidou, Paris; Musée de la Chasse et de la Nature, Paris; Muséum d’Histoire Naturelle, Paris; ICA, London; BALTIC, Gateshead; Obsidian Coast, Bradford-on-Avon; Goldsmiths College, London; The Showroom, London; Pump House Gallery, London; ZKM Karlsruhe, Art Laboratory Berlin; HDKV, Heidelberg; Harvard Graduate School of Design, Cambridge MA; Verksmiðjan á Hjalteyri, Iceland and The Húsavík Whale Museum, Iceland.

Architecture of the Enclosed Sea. Between Aquaria and Marine Protected Areas explores the architectural, geopolitical and historical resonance of two spatial techniques for knowing and governing marine life in the modern era. The public programme, curated by Louise Carver and developed by maat and TBA21–Academy, compares the respective characters of the aquarium and the marine protected area in ocean cultures and marine conservation. The programme inquires and speculates about the architectures of ocean enclosures at the start of the UN’s “Decade of the Ocean” and it considers the territorial imaginary of enclosed water and the material artefacts which hold it in place, with talks and events that bring to life the dynamics which overflow the fixed boundaries of boxes.