What purpose does art serve? Nothing… But it can provoke intense emotions. It can even drive you crazy

Gabriel Abrantes — "Les Extraordinaires Mésaventures de la Jeune Fille de Pierre", 2019.

It’s a provocative opener to his short film, Les Extraordinaires Mésaventures de la Jeune Fille de Pierre [The Marvellous Misadventures of the Stone Lady] (2019) a film exploring how a sculpture comes to life and escapes its confinement from the famous Louvre Museum, Paris, shown at the beginning of his solo exhibition at maat. It could also be a way in which Gabriel Abrantes describes the purpose of his oeuvre. As a student, he tussled with the question of the use of art during his studies at The Cooper Union, New York, the École nationale supérieure des beaux-arts, Paris, and at Le Fresnoy, a post-graduate art and audiovisual research centre. Early works such as Olympia I & II (2006) made in collaboration with Katie Widloski whilst still at The Cooper Union acted out questions around realism and representation raised by Édouard Manet’s famous 1863 portrait of a prostitute (Olympia) elevated to the pose of a classical beauty. This work is not in the show but informs it: the juxtaposition of references to art and cultural history with personal and socio-political commentary is a guiding thread throughout Programmed Melancholy. Whilst Abrantes’ body of work is abundant, the show is concisely selected, it features five moving image works and a VR work, interspersed by a series of drawings and paintings, which reveal his twofold interest with art and the moving image.

Abrantes moved quickly through the art school irony manifested in Olympia to focus on what art can do: at best it can profoundly affect you. His works engage with our emotions, with a range of personal feelings, often humorous, potentially rousing ethical and political beliefs. Unstable, multi-faced, polysexual, his characters waver between expressing personal emotions and wider social, environmental and political concerns. We empathise with the robot drone Andy Coughman’s paradoxical crush on Jo in Os Humores Artificiais [The Artificial Humours] (2016) and regretting being “merely an algorithm” in Coughman’s Lament (2020), only later to feel disappointed when Coughman has been reprogrammed by their creator Claude Laroque to forget their initial “feelings” in an attempt to achieve fame through performing stand-up comedy. As we drift through the work and the show, Abrantes’ disembodied characters become believable, bringing to light recurrent questions around whether AI or objects can develop feelings and humour, and what this means for our future relations.

"Visionary Iraq" (Gabriel Abrantes and Benjamin Crotty, 2008). View of the exhibition "Gabriel Abrantes. Programmed Melancholy" (maat, 12/02 – 24/08/2020). Courtesy of the artists and EDP Foundation, Lisbon. Photo: Bruno Lopes

Video still from "Visionary Iraq" (Gabriel Abrantes and Benjamin Crotty, 2008)

Video still from "Os Humores Artificiais" (Gabriel Abrantes, 2016). Super 16mm film transferred to 2K, 29 min. With Margarida Lucas (voice), Patrícia Soso (voice), Amanda Rodarte, Gilda Nomacce and Ivo Müller

With the support of Fundação de Serralves, 32ª Bienal de São Paulo, Colección Inelcom (Madrid), ICA – Instituto do Cinema e do Audiovisual and Ministério da Cultura de Portugal. Produced by Artificial Humors. Courtesy of the artist and EDP Foundation Art Collection

(left) "Os Humores Artificiais" (Gabriel Abrantes, 2016). View of the exhibition "Gabriel Abrantes. Programmed Melancholy" (maat, 12/02 – 24/08/2020). Courtesy of the artist and EDP Foundation, Lisbon. Photo: Bruno Lopes

Coming back to the title of the exhibition, translated as “Programmed Melancholy”, it can be read in different ways: it brings together works whose uniting character traits are melancholy or disillusion, which can be seen in the escapist, idealist sculpture in Jeune Fille, a duo of pro-democracy Iraq volunteers in Visionary Iraq (2008), three environmental scientists in Too Many Daddies, Mommies and Babies (2009), and the modernist artist Brancusi and the feminist writer and wealthy heiress Marie Bonaparte in A Brief History of Princess X (2016). It is fitting to explore these concepts in the Portuguese context, attuned with the concept of saudade, or melancholic longing for something or someone whom they are missing, which may be a latent theme in Abrantes’ works that operate around and centre on issues of globalisation. (→ 1) With increased movement of bodies, or its inversion through restricted movement — for instance due to the Covid-19 pandemic whilst I am writing this text — comes longing for elsewhere, and trails of missing friends and family.

The title also suggests that emotions can be programmed, encoded for instance through AI into Coughman’s system in Os Humores Artificiais, that audiences can also be influenced by film director Abrantes, his co-directors Benjamin Crotty, Daniel Schmidt and other collaborators. It could also point to the ways in which the moving image works have been curated in the space, offering different physical experiences: in relation to painting, to sculpture, re-enacting the work's original film set or gallery installation, as a large black box projection, or as an absorbing VR work... The title may be tongue in cheek, but ultimately Abrantes makes a point: much of our emotions and the vocabulary we are accustomed to are “programmed” or churned out in a series of codified gestures, character traits and relations and stock phrases from Hollywood to Netflix, via memes and social media. This also goes for the cinema and art worlds’ ecosystems and jargons that are also being challenged by multiplying screens and decreasing attention spans. Abrantes’ work offers a satire of society and media, using the tools of high and popular art forms, mining symbols from one and codes from the other to create work that is legible to many and therefore also effective in different contexts, from the gallery, the silver screen to virtual reality.

-

(1) See interview with Justin Jaeckle, Contemporânea, June 2020.

Wittgenstein said the most profound problems could only be addressed in the form of jokes.

Gabriel Abrantes — Os Humores Artificiais, 2016.

Taking inspiration from myths, fairy tales and history, Abrantes uses narrative tools to create satirical stories speaking of possibility and failure. These are married with a nimble, incessant assemblage of cultural references informed by the possibilities opened up by deconstructionist theory post-“death of the author”. Language and image in his work are open to endless juxtapositions including to the new possibilities offered by VR. (→ 2) He asks us to pay attention to the language on a micro level to express wider structural issues: how emotion for example is defined within narrow heteronormative parameters. He points to societal issues, politics and post-colonial legacies. For instance, Abrantes parodies the language of telenovelas, cartoons and Hollywood, tackling clichés head on, yet the characters voice stock phrases in unexpected situations: “I love you till my heart will burst” exclaims robot Coughman to indigenous Yawalapiti girl Jo in Os Humores Artificiais; “We can’t keep trying to save the Amazon”, “Let’s start a family” and “I believe in Rob and Ryan” caricatures a homosexual couple’s shift from a quest to save the Amazon to surrogate parenthood in Too Many Daddies…

Repeating lines with a poised and placid syntax, many of his early works show Abrantes collaborating with non-professional actors to deliver lines on cue as though they are digesting what they are saying at the same time as us. Sometimes the characters seem emotionless, deadpan, making the audience become aware of the filmmaker’s linguistic deceit to push our comfort zone. This is most apparent when controversial questions are tackled head on such as sexual and familial relations or politics, for example Manel and his adopted sister “have been fucking since we were 14”; “I just don’t know if Democracy is possible anymore, at least in Iraq” (both Visionary Iraq).

-

(2) Whilst Abrantes is critical on “overreliance on the postmodernist discursive allowance for fragmentation” in Contemporânea, he acknowledges the influence of deconstructionist theory around the relation of moving image and language, quoting Jacques Derrida’s “There is no outside-text”. Conversation with the artist 29 April 2020.

In one of her university lectures in Os Humores Artificiais, Coughman’s maker Laroque suggests that “to create jokes you must defy the rules of grammar… you must create unexpected contrasts”, positing elements in new situations. She successfully programmes Coughman to declaim absurd jokes: “I just bought my first iPhone… now I need a pair of trousers to put it in.” The possibility of humour is, according to Laroque, when “negative is transformed into positive” and “silliness is transformed into empathy”.

Whilst Abrantes takes us on a physical journey in the exhibition from Paris, Brazil, Portugal, Iraq and back the languages in his works are incongruous. In Too Many Daddies… the character Ngetu speaks an unspecified Amazonian Indian language, he later inexplicably switches to Portuguese, the character’s main language and that of the location (Brazil). With their hammy names Rob and Ryan, the main characters may actually be American, and the loose dubbing of the work leaves open the possibility they are speaking in the lingua franca English. In Visionary Iraq the Portuguese protagonists are speaking English, acknowledging the influence of the American series The O. C. (2003-07) on the situation and dialogue, but also perhaps pointing to Anglo-Saxon nation’s roles in the conflict. In Princess X Abrantes’ voiceover of the story and the protagonists’ dialogue is English rather than French. Playing with our linguistic expectations and questioning concepts of dominant and minor languages, Abrantes mines the gaps between languages and understanding at the frontier of globalisation.

Video stills from "A Brief History of Princess X" (Gabriel Abrantes, 2016). Super 16mm film transferred to 2K, 7 min. With Gabriel Abrantes (voice) Francisco Cipriano, Joana Barrios and Filipe Vargas. Produced by Artificial Humors and Les Films du Bélier. Courtesy of the artist and EDP Foundation Art Collection

Navigating the tightrope of language and humour, Abrantes’ works are centred on his own experience: he often holds several roles beyond director; he has often been an actor (Olympia, Visionary Iraq…) or narrator (Princess X). With his collaborators (Crotty, Schmidt, Widloski…) he pays tribute to early author cinema and experimental cinema which is often self-funded, self-organised and linked to personal experience, Kenneth Anger, the Kuchar Brothers, Andy Warhol or the confessional style of Ryan Trecartin being points of reference. Far from doing this in a biographical or self-centred way, Abrantes revisits the possibilities of cinematic authorship drawing from his experiences and collaborations across the globe, juxtaposed with a strong narrative arc (→ 3).

Conversely, in his more recent works, his non-human characters — Coughman, Princess X or Jeune Fille — express strong emotions, encouraging our compassion. By offering language and emotions to objects, he instils these characters with linguistic possibility and signification, encouraging us to reconsider our anthropocentric view of the world. By highlighting different subject positions, grammatical, linguistic and geographical constructs through the use of humour, Abrantes pushes his narrative and his filmic language to the absurd. In this way, he is able to tackle controversial topics whilst also folding in a variety of cultural references.

-

(3) See Andréa Picard, “In the Age of Contamination: Gabriel Abrantes’ Tall Tales and Tainted Love”, Cinema Scope, cs53, 2013.

Experimental cinema has often taken inspiration from art and painting for its “ability to go beyond speech” (→ 4). Programmed Melancholy is also a journey through Abrantes’ engagement in art history. From Olympia his works have unfolded in a series of tableaux from the claustrophobic, staged interior scenes of reclining bodies and conversation pieces in Visionary Iraq and Too Many Daddies…, to the expansive urban or landscape vistas in Os Humores Artificiais and Coughman’s Lament, they also trace the intimate setting of an artists’ studio in Princess X and a visit to the repository of global culture, the Louvre Museum. Jeune Fille offers a tour of some of the Louvre’s highlights including: The Victory of Samothrace (2nd Century B.C.), Jacques-Louis David’s Coronation of Napoleon (1807) and Eugène Delacroix’s Liberty Leading the People (1830). He contrasts these French cultural heavyweights with the “refreshingly banal” marble sculpture of a girl listening, in a deliberately derivative neo-classical style generated by his digital editing tools.

-

(4) Interview with Jean-Luc Godard and Lionel Baier, ECAL, Lausanne instagram live, 10 April 2020.

Video stills from Les Extraordinaires Mésaventures de la Jeune Fille de Pierre (Gabriel Abrantes, 2019). Film in 8k, 20 min. With: Liza Lapert Vimala Pons (voice), Virgile Vernier, Brigitte Fontaine (voice), Alexis Manenti (voice) and Caroline Deruas. With the support of ICA – Instituto do Cinema e do Audiovisual and Ministério da Cultura de Portugal. Produced by Les Films du Bélier and Artificial Humors. Courtesy of the artist

"Les Extraordinaires Mésaventures de la Jeune Fille de Pierre" (Gabriel Abrantes, 2019) and "Reclining figure with black and white fur (Cat Lady)" (Gabriel Abrantes, 2020). View of the exhibition "Gabriel Abrantes. Programmed Melancholy" (maat, 12/02 – 24/08/2020). Courtesy of the artist and EDP Foundation, Lisbon. Photo: Bruno Lopes

The two catalyst characters in Jeune Fille are the Victory of Samothrace and a turquoise glazed Egyptian figurine of a hippopotamus (c. 3800 – 1710 BC), both being some of the most popular items in the collection, the latter is affectionately dubbed Jean-Jacques in the film. These are chefs-d’oeuvres (masterpieces) in both senses of the word as they literally wake and lead the other characters around the museum at night, and they also comment on these works’ enduring capacity to “provoke intense emotion”, to illustrate History (Hellenistic Culture, the rise of Napoleon, the French Revolution…) and so as cultural symbols to gain new meaning in different contexts. The underlying story of Jeune Fille is a journey of its escape into the streets of Paris, its participation in a protest in high-viz gear in the wake of the gilets jaunes protests, its chase and beating up by the police. The work gets literally and metaphorically damaged and subsequently repaired in the Louvre conservation studio, becoming ironically a restoration success story for the public. Her human counterpart, the self-styled museum-guide “Dante Fragonard”, also appears in a neck brace, mirroring her physical and emotional damage. By reflecting their joint experiences, the artist explores the possibilities of feelings that both objects and humans can experience. In the same way he has bestowed emotions to Coughman, Abrantes shifts our viewpoint to that of a non-human subject.

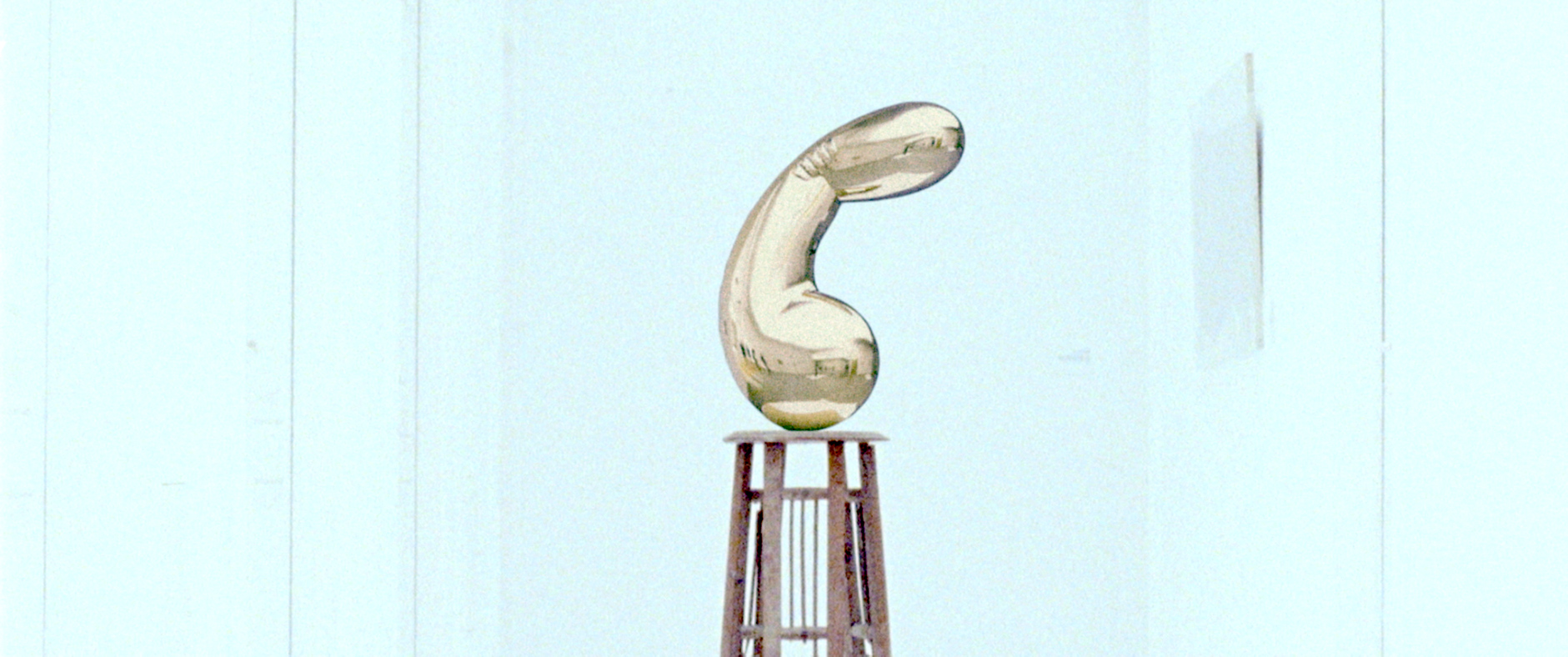

In a similar way, Princess X humorously dissects the biographies of Constantin Brancusi and Marie Bonaparte, weaving them around the central figure of the sculpture to map out the history of its making and controversial reception. The film mines the sculpture’s indeterminate signification: a highly polished abstract phallus representing “the essence of woman” subject to schoolboy jokes, as well as a cruel portrait deriding a wealthy woman’s quest to further her own satisfaction in the name of pioneering psycho-sexual research. Here, Abrantes mixes juvenile humour with the satirical reactions to the sculpture’s modernist aspirations after its curtailed exhibition at the Salon des Indépendants, Paris, in 1920.

By bringing to life inanimate objects, Abrantes pays tribute to early animation, to video games, myths and fairy tales. Jeune Fille might also be a response to a question raised by artist and filmmaker Jean Cocteau in his oneiric The Blood of a Poet (1930), which depicts an artist’s struggle with creativity and pays tribute itself to the Ovidian story of Pygmalion who believed his sculptural representation of a woman was so perfect it came to life. Cocteau asks the rhetorical question: “Is it not crazy to wake statues so suddenly from their secular sleep?” In his film, Cocteau explores the relationship of artists, their work, matter and death, suggesting they have to undergo a number of “deaths” in order for their work to achieve immortality. A source of inspiration for Abrantes’s shift between popular and “high” culture, his lush scene settings and use of analogue film and his interest in dealing with taboo questions is without a doubt Pier Paolo Pasolini. Pasolini also pushed the analogy of film and death, cinema being according to him a way to capture the present whilst montage being a way of fixing images and to perform “what death accomplishes for life” (→ 5).

Yet by waking and breaking statues, by playing with language, by quoting and parodying, Abrantes is no iconoclast. Moving beyond ideas around the “death of the author” he invokes and pays tributes to artists and artworks, folding them back into the present. Sculptures, scientists, teenagers, artists, robots and writers’ experiences are levelled on screen. Exhibition and drawings, cinema, VR and set collide. Perhaps his fertile imagination has also found solace in Wittgenstein’s Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus “Death is not an event in life: we do not live to experience death. If we take eternity to mean not infinite temporal duration but timelessness, then eternal life belongs to those who live in the present. Our life has no end in just the way in which our visual field has no limits.” (→ 6) Abrantes opens our screens and horizons to the unbounded experiences of the present.

-

(5) Pier Paolo Pasolini, “On the Long Take”, 1967 in Campany D. (ed), The Cinematic, Whitechapel Gallery/MIT, 2007. See Also Abrantes’ article on “The Delay of Death – Pasolini’s Trilogy of Life”, Mubi Notebooks, mubi.com, published 24 December 2012.

-

(6) Ludwig Wittgenstein, Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus, 1922, Dover Publications, New York, 1999, 6.4311, p. 106.

Emily Butler is a curator, writer and translator. Since 2010, she has been a curator at Whitechapel Gallery, London, where she works on the ongoing collaborative project Artist's Film International, on exhibitions drawn from the collections, on commissions by artists such as Rachel Whiteread, Kader Attia, Carlos Bunga and Nalini Malani, or group exhibitions like "Electronic Superhighway (2016 – 1966)".

The essay “Gabriel Abrantes: the present unbounded” by Emily Butler is included in the book Gabriel Abrantes. Programmed Melancholy, published by maat / EDP Foundation and Mousse Publishing, in 2020, on the occasion of the homonymous exhibition, curated by Inês Grosso and presented at maat (Central, 12/02–24/08/2020).