MAAT MODE — THE PEOPLE INTERVIEWS

This series of informal conversations aims to disclose the ideas and research behind a selected number of projects commissioned for maat Mode 2020. Some of these dialogues were recorded during the lockdown in April and May 2020, while others were held live in the maat Media Room, a space designed as part of Beeline, SO – IL’s museum-wide architectural intervention.

maat / Beatrice Leanza

Today we speak with André Tavares, a published author and architect based in Porto. He has curated many exhibitions, amongst them the 4th edition of the Lisbon Architecture Triennale in 2016, and has been running Dafne Editora, a publishing house, since 2006. He is also the curator of Garagem Sul in Lisbon, a space dedicated to architecture and part of CCB – Centro Cultural de Belém, which is located in the close vicinity of maat.

This is in fact our first institutional collaboration. It is connected to an exhibition that you were able to open just before we were all forced into home confinement. Maybe you can tell us a little bit about the show.

André Tavares

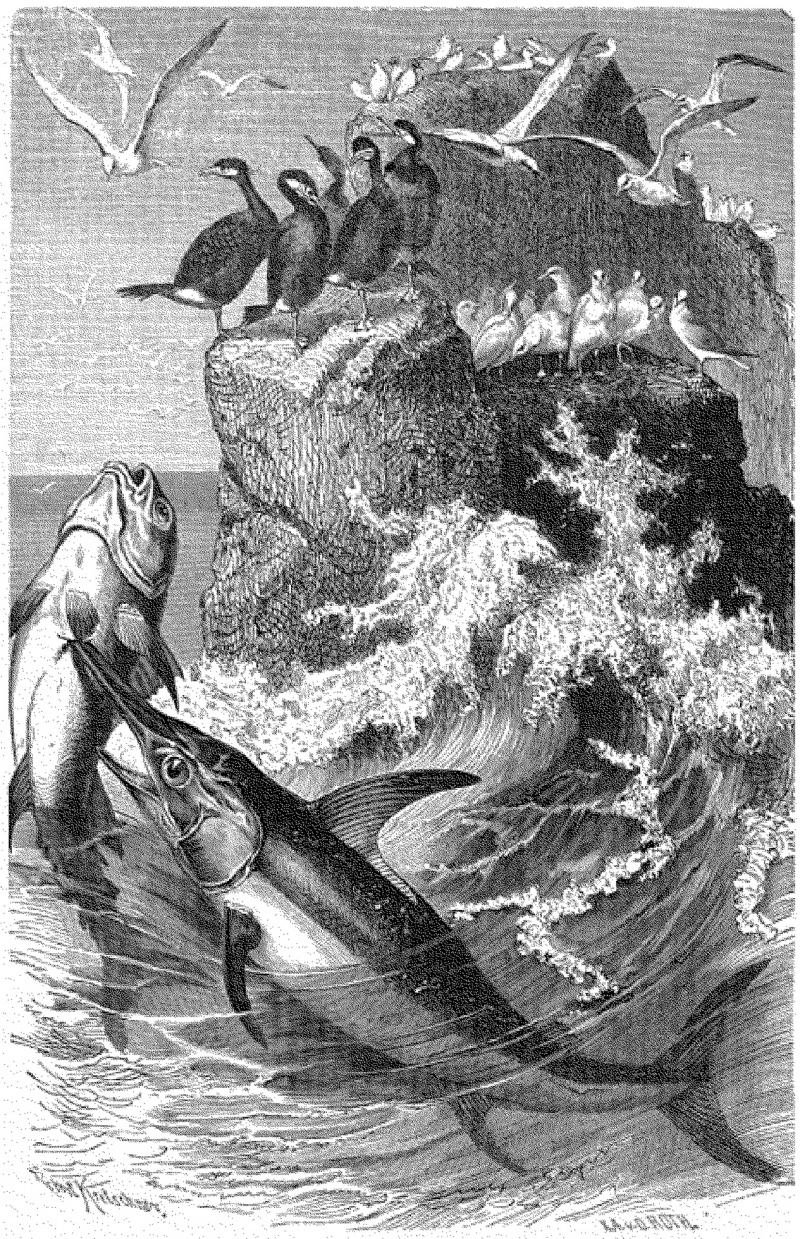

The show is called Our Land Is the Sea and delves into the idea of a reversal of the given situation. As architects, we usually think of land as a support for our design practice, but here our perception is that land needs to be understood on a planetary scale and, of course, the oceans are a key element if we are to understand what is going on. When we design onshore, we need to have a much better understanding of the dynamics of the oceans in terms of marine ecosystems, hydrodynamics, the currents, and how all these elements operate and how these natural environments define the continuity of ecological systems as they transition between land and sea.

That was the motor, as it were, the origin of the exhibition which has been developed with a group of architect colleagues from Figueira da Foz. For many years now they have been wondering, based on their surfing activities, how to read the sea and how to read the ongoing transformations of the landscape in their city. In short, they have been looking at how the relationship between the city and the sea has changed in recent years.

maat

There’s one line in the description of the show that I find quite telling – where you say, “the sea is a place: instead of considering the ocean as a boundary or a space of confrontation, we can and must reimagine it as a partner in the construction of the land.” The programme you have developed with us for maat Mode is titled Architecture Follows Fish. Tell us more about it.

The lugger Delães taking part in the blessing of the cod-fishing fleet in Lisbon prior to being sunk by the German submarine U-96 in September 1942. Courtesy of Museu Municipal de Etnografia e História da Póvoa de Varzim.

At a certain point we began to realise that we could understand the transformation of the city in relation to the transformation of the fish ecosystems in the ocean.

André Tavares

André Tavares

One of the sections of the exhibition deals with this research project that I’ve been conducting at the architecture school in Guimarães, which looks at this connection between marine ecosystems and urban transformation. (1) Its basic hypothesis is that a cod landscape is different from a sardine landscape, which is different from a whale landscape, and so on. This allows us to understand the ocean in relation to its biological dynamics, where the phytoplankton is, where the food for the fish is, the relationship between the continental shelves and the shore, and how it generates a certain kind of fishing practice that has a landscape counterpart. At a certain point we began to realise that we could understand the transformation of the city in relation to the transformation of the fish ecosystems in the ocean. That’s why we proposed the further development of this hypothesis with maat. This provided a very convenient collaboration between our two spaces, and we invited some colleagues from the USA and Hong Kong to explore different ideas of this relationship between fish and the city.

maat

Can you give us some examples?

André Tavares

One of them is Carson Chan, an architecture writer and curator whose doctoral research at Princeton is about aquariums. Aquariums are not only a representation of what’s happening in the marine ecosystems but are also completely human-controlled life support systems. Carson has been developing an interesting take on how men can operate on the concept of nature through aquariums. His idea was to develop a “Theory of the Aquarium” – as Lisbon has two famous examples – and understand how fish are represented and studied, and how human actions affect our planet.

Another comes out of MAP Office, devised by Laurent Gutierrez and Valérie Portefaix, a duo of artists/architects who have been based in Hong Kong since 1996. They have been working, with extraordinary results, on architectural representation through drawing, photography, and installations and have been surveying how human beings live in various contexts. In recent years, they’ve been very attentive to what’s happening in the sea and especially with fishing practices. It’s a kind of ethnographical way of reading how boats, fishing nets, fishermen, and fish contribute to building a collective memory. So, they proposed “Fishing Histories” as a title for their section of the workshops, which explores some harbours and fishing communities that still exist around Lisbon, e.g. in Trafaria, Sesimbra, and Peniche and areas close to them: their idea was to collect materials, images, reminders of the past, movies, texts, and all the different representations of fisheries in order to create an atlas that would illustrate this visual legacy.

maat

You are also leading one of the workshop modules yourself?

André Tavares

Yes, that will be the “Lisbon Cod Map,” which aims to represent all the strategies that were put in place within the city, particularly in the post-war period, i.e. in the 1940s, 1950s, and 1960s. This means not only the fishing facilities – or the processing facilities for cod fisheries, which were still very popular in Portugal (with fishing on the distant high seas bringing salted cod to dry on the south bank of the Tagus in Lisbon) – but also all the apparatus necessary to build an ideology of cod: the big parades of fishing boats and monumental freezing facilities that have a very strong urban impact, some of which are also very close to maat. The idea is to represent the practice of fishing through buildings as well as the relevant companies based in the city, how the warehouses and how all these networks for the processing of the cod create an image not only for the city but also for the country as a whole.

So, through these three kinds of narrative we will try to develop a physical relationship with Lisbon and its fishing landscape and so understand that the image of the city is very closely connected to fish. This image also changes when fish stocks collapse for instance, which happened with cod fishing. When there was no more cod, the landscape of the city changed, and cities also change the marine ecosystem because they voraciously eat all the fish swimming in the ocean.

maat

I know that you are part of a research project that is being conducted as part of your teaching on a related subject. Is that correct?

-

(1) The research project The Sea and the Shore, Architecture and Marine Biology: The Impact of Sea Life on the Built Environment (PTDC/ART-DAQ/29537/2017 has the financial support of the FCT/MCTES through national funds (PIDDAC) and co-financing from the European Regional Development Fund (FEDER) POCI-01-0145-FEDER-029537, in the aim of the new partnership agreement PT2020 through COMPETE 2020 – Competitiveness and Internationalization Operational Program (POCI).

André Tavares

Yes, the research project we are carrying out in Guimarães. Our goal is to work on an Atlantic history of architecture and to better understand the connections and networks that operate throughout the North Atlantic. Through cod fisheries but also with sardine fishing in the Atlantic off Southern Europe. By reading architecture, the idea is to grasp how these dynamics generated technological transfers and movements within cultures on both sides of the Atlantic.

We would like to build up a history of architecture not based on the respective countries and on their land policies but on the shifts and movements of the fish stock, on how species behave in the ocean. Ultimately, we could write a North Atlantic architectural history instead of an American history or a French history or a Portuguese history. This view is fundamental if we are looking to global resources and to oceans, because ultimately all boundaries are socially fabricated. We understand that very easily in the case of land, which through social policies has become more and more characterised by language limits and so on, but these limits are even more fabricated within the oceans where fish couldn’t care less about borders and economic zones.

maat

So, we are really thinking of a different landscape archaeology. Given recent events, with the outbreak of Covid-19 and the complete rethinking this has imposed upon us when we speak of spaces, of belonging, of border zones, how is this affecting your approach to the research matters you have touched on here?

André Tavares

I was very impressed with a discussion among fishermen commenting on the waste generated by networks to distribute the catches. With the lockdown, they only operate with major distribution companies, so that supermarkets can guarantee that there are no viruses in the food. They only sell cheap fish; they no longer sell to restaurants or specific buyers, and this is having a tremendous impact on fishing. This could lead to the rapid devastation of a certain species that a very specific market is interested in. It diverts fishing practices to a very specific, very controlled, and mono-focused market. And to low-cost fisheries, which do the most damage to ecosystems.

We would like to build up a history of architecture not based on the respective countries and on their land policies but on the shifts and movements of the fish stock, on how species behave in the ocean.

André Tavares

-

Architect José Pedro Fernandes engaged in fieldwork, Póvoa de Varzim, 2020.

maat

By way of conclusion, I am curious to know, since you teach at a university, how your architecture students react to this encounter between the built environment and the marine ecosystem. I wonder if there are any particular stories you’d like to share.

André Tavares

I think they are curious, and they are also a bit suspicious in general because that’s not what they imagine architecture is. There is quite a common, long-established expectation that architecture is about designing buildings and one does not think of the system the building belongs to. But when they engage with the idea, they can literally go wild! There’s this very enthusiastic colleague of ours who just completed his degree. His master’s thesis focuses on the fishermen of Póvoa de Varzim and on the territorial aspects of the fish traps they use. It’s a very specific type of fishing that operates in very rocky environments where you cannot use drag nets. He would regularly go out with the fishermen and became very enthusiastic – there is a very beautiful picture that he included in his thesis that shows him doing field work, and you can’t really tell who the architect is and who the fishermen are!

André Tavares is an architect and has been running Dafne Editora. With Diogo Seixas Lopes he was editor-in-chief of the magazine Jornal Arquitectos (2013–2015) and in 2016 co-curator of the 4th Lisbon Architecture Triennale, "The Form of Form". His book "The Anatomy of the Architectural Book" (Lars Müller/Canadian Centre for Architecture, 2016) addresses the crossovers between book culture and building culture. Currently he is a researcher at Escola de Arquitectura da Universidade do Minho, in Guimarães, and consultant of Garagem Sul Architectural Exhibitions, in Lisbon.

The series of workshops Architecture Follows Fish aims to understand the architectural phenomenon happening on the shore as the consequence of both the natural and the unnatural dynamics of the sea. It brings together architects, scholars, reporters, biologists, and authors who have dealt with a range of subjects relating to Fishing Architecture. This series of workshops is a collaboration between maat, CCB Garagem Sul, and the Fishing Architecture research group, and is an offshoot from the exhibition "Our Land is the Sea: The Sensitive Construction of the Coastline" (CCB Garagem Sul, 10/03–09/08/2020).