Work, Sound, Word and Laziness. Joshua, Martha, Rhann and Kross

by Gonçalo M. Tavares

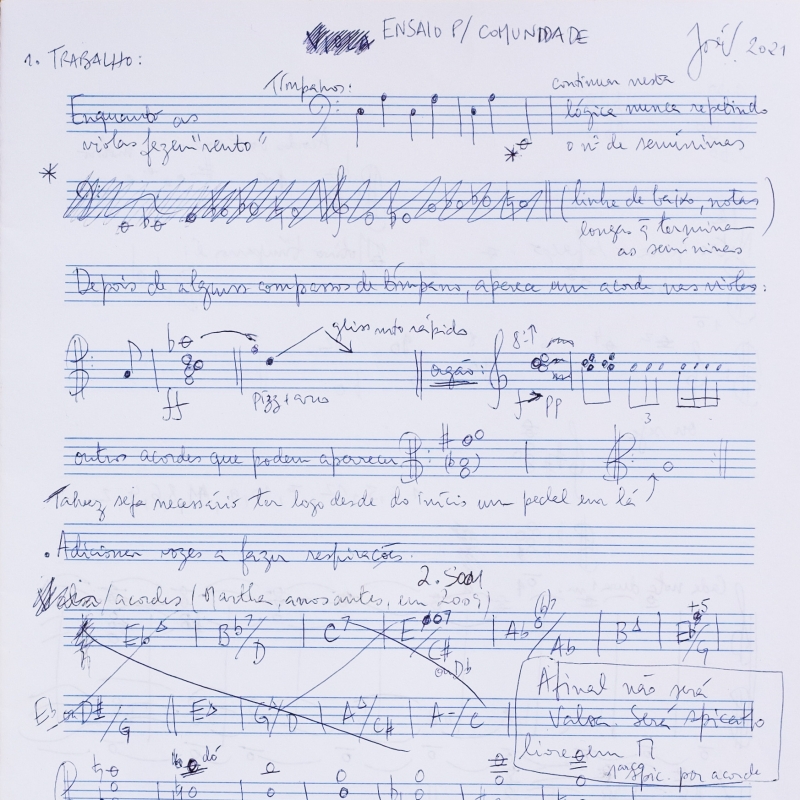

An original literary composition for the exhibition REHEARSAL FOR A COMMUNITY – Portrait of a collection under construction (take 1).

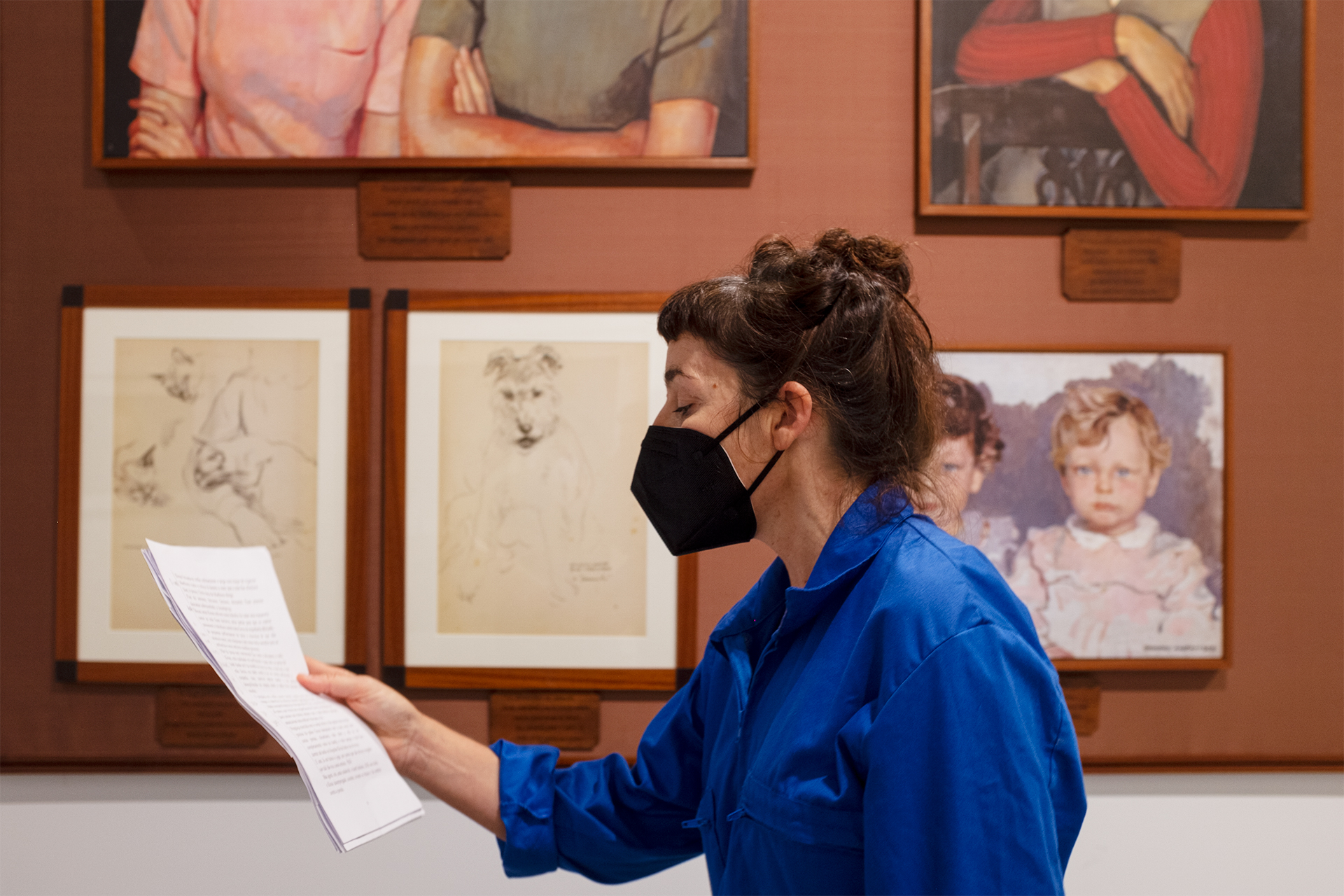

“PERFORMING THE EXHIBITION # 1” (maat, 22/05 – 23/05/2021), with Ana Brandão and Ricardo Vaz Trindade, who carried out a performative

reading based on the exhibition concept and the original text by Gonçalo M. Tavares, was presented at Central Tejo in the context of the exhibition “REHEARSAL FOR A COMMUNITY – Portrait of a collection under construction (take 1)” (maat, 24/04 – 31/01/2022). Photos: Paulo Mendes Archive Studio.

The text “Work, Sound, Word and Laziness. Joshua, Martha, Rhann and Kross”, an original composition by Gonçalo M. Tavares for this exhibition, is a family story developed in four moments, accompanying the four words that conceptually underpin the exhibition: a father working with fire that alters the form of things, the shapes that produce a sound, delusion and fear, tension, the knife that remains in the hand.

1 – Joshua and work

In his hands he clutches an old calendar, from 1942.

Joshua stands before the fire like a man stands before their father on his deathbed. The body, though all in one piece, motionless, laid straight out, looks somehow different – looks somehow completely the same as it always has, and at the same time, like the body of a complete stranger.

Joshua’s father had always been like that: both his complete double and his complete opposite. His face was like Joshua’s but further ahead, in some kind of race through time. And his father remains in the lead; Joshua trails behind. He placed second, and he is bitter because of this, too.

My face a few years from now, Joshua would think, when he looked at him, at his father; an alive mirror seeing into the future – or rather, laying a curse upon it.

Joshua could not like the creases and furrows of that face which one day would be his very own. These are not the sort of features one finds in a good man, he thought.

He respected the fire here in front of him just the same way he respected his father, that is, on account of its absolute difference: get too close to it, and he would die. This is what fire does: alters the state of things. Joshua uses this property for his work, uses it to transform the fragment of the world before his hands. Fire slackens a material’s toughness, allows it to be reshaped. This is what Joshua needed in order to exist, a flame that would not kill him but instead reshape him and alter his course.

That being said, Joshua is crazy or if not crazy almost or quite nearly or at least is someone who wishes to escape this demented place.

He is a blacksmith that has taken to howling in front of a window every so often, like some sort of clock. The people of the village are already well acquainted with him (no, he’s not crazy, he just howls); halfwolf, half-timekeeper; Joshua howls at midday on the dot, accompanying the ringing of the church-bells and the tight pack of workers leaving the factory for their lunch break.

He will not be having lunch himself, since, according to him, he lost all of his appetite the moment he saw his father’s dead body lying in the church. I stopped getting hungry, he says. I’ve not taken a single order from my stomach since.

I work, he says, but not for the money. I do it in order to be close to the fire – an element, he says, that has become his friend.

Because his two children had been taken away, Joshua needed to invent things.

“PERFORMING THE EXHIBITION # 1” in the section Work of the exhibition “REHEARSAL FOR A COMMUNITY – Portrait of a collection under construction (take 1)”. Photo: Paulo Mendes Archive Studio.

“PERFORMING THE EXHIBITION # 1” in the section Work of the exhibition “REHEARSAL FOR A COMMUNITY – Portrait of a collection under construction (take 1)”. Photo: Paulo Mendes Archive Studio.

So he said he had two friends: the fire, and the knife.

Those sacks he keeps in the old storeroom are not his friends, because they are very heavy. He cannot carry them around with him. But the fire and the knife, on the other hand, those he can.

A man’s friends must be light, he says.

Those heavy sacks are filled to the top with stones; the aimless project of an insane person: holding on to things that have no value, things abundant beyond the house. As if every stone in the world might just up and vanish.

Joshua thinks back to the war and says: a man must keep hold of his stones. But to what end? It was unclear. Did he mean to use them to throw at things, to construct a wall – some kind of bunker, maybe?

Sometimes, Joshua goes out at night with a lantern and begins to howl as if he were a wolf under the full moon. The townspeople go to their windows to see what the matter is and when they figure out it is only Joshua, they shut their windows up tight and place an extra latch on their doors and allow themselves to be vigilant a few moments – but not long afterwards they forget about it, and perhaps even manage to get to sleep.

A madman who has grown elderly ceases to be a threat. This has always been the way.

But then one day, everything changes. Joshua leaves the house that day with something in his pocket, with that wieldy little friend of his, cold and mute and compact, ready to come out and defend him at any moment: the knife.

“PERFORMING THE EXHIBITION # 1” in the section Word of the exhibition “REHEARSAL FOR A COMMUNITY – Portrait of a collection under construction (take 1)”. Photos: Francisco Craveiro (By Agency), courtesy of EDP Foundation / maat.

2 – Rhann and the word

We are in 2014 and Rhann is standing under an enormous neon sign in the middle of the desert. He wonders whether he might be hallucinating or seeing a mirage, but then mirages are old-fashioned things – they promise you some water, a woman, or some money – and do not tend to appear before tired, thirsty eyes in the form of giant placards with glaring neon signs. But this is precisely what Rhann sees in front of him: right in the middle of the desert, amidst all that yellow sameness, some bright, sparkling words have appeared.

He closes his eyes at first, straight off, since the light is far too bright – the lights on the display reflect the fierce brightness of the desert sand and it is a brightness no human could bear.

But eventually Rhann opens his eyes and amidst the brightness he makes out a few letters:

J E S U S

is the precise word he reads in sharp outline

J E S U S

He had been expecting this, Rhann.

He gets down on his knees: this must be what the sign wants from him, he thinks, it wants him to get down on his knees and start praying; actually, to pretend to start praying, since by now he has forgotten pretty much everything – he can remember the start, Our Father who Art in Heaven... but as for the rest, he has completely forgotten it. He was in Heaven, right, yes, that he could remember... but doing what exactly?, he thinks.

“PERFORMING THE EXHIBITION # 1” in the section Word of the exhibition “REHEARSAL FOR A COMMUNITY – Portrait of a collection under construction (take 1)”. Photo: Paulo Mendes Archive Studio.

Rhann is thirsty, he has an excuse.

I’ve forgotten it because I’m unwell, he says to the sign, as if it were a person with ears and empathy.

But this is what Rhann does, starts talking to it. He gets to his feet, tilts his neck back, and starts talking to the giant placard.

It is, yes, enormous. Maybe ten metres tall. So Rhann has to have his neck tilted back like that, gazing upward like someone addressing a god, some totem infused with electrical power, a modern totem.

Some artificial desert animal, Rhann thinks, some animal that only appears to men who are completely exhausted, to men beginning to experience hallucinations of the visual and auditory sort.

It is vital not to forget the word – he thinks – if I forget words, I’ll go mad and then I’ll die out here in the desert.

And so he thinks back to the alphabet, as if he were six years old again. The first letter that pops into his head is the letter G.

But he is well aware that the alphabet does not begin with G, but rather with the letter A.

And so from there, he begins, reciting the alphabet to himself as if it really was some sort of prayer

A b c d e f g h i j k l

He takes a pause for a moment; it really does look like he is addressing some god or another; on his knees like that in front of an enormous billboard reciting his six-year-old-boy’s prayer, and he must be starting to hallucinate again, and it must be getting worse, too, because very soon he begins to recall another one of those prayers from when he was six and begins

2×2 = 4, 2×3 = 6, 2×4 = 8, 2×5 = 10, 2×6 = 12, 2×7 = 14, 2×8 = 16, 2×9 = 18, 2×10 = 20

And stops there.

His times tables and the alphabet, these he can still remember. So he can’t have already died, then. Dead people do not know their times tables.

He cannot remember his Lord’s Prayer, but he can remember the alphabet and his times tables.

Which of these would he prefer to have forgotten: the words to his prayers, the alphabet, or his times tables? He suddenly recalls the sentence from a book – but he doesn’t want to think of an answer, he hasn’t got the time, there’s a scrambling in his head, a psychic scramble.

He goes back to saying the alphabet

A b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y Z

And when he arrives at Z, he feels a tremendous sense of satisfaction, as if he had just completed some piece of homework. Then Rhann starts to think that that was all his life had been: homework.

He was married, had children, a job, feels himself rather old now, and yes, throughout all of it, he had merely been doing his homework. But then who was it that had given him all that homework to do in the first place? God, he thinks, it certainly wasn’t God, it can’t have been, God had not once entered into his home... the homework that Rhann has been doing for decades now: become married have children go to work say hello to people passing by in the street – this set of homework was one that had been given him by his father. His father, right, yes, that was it.

Rhann stopped thinking.

Now he begins to weep, or if not, it must be the violent desert moon blistering his eyes, as if its light were not coming down in waves but instead in the form of mosquitos pricking into his eyes in order to puncture them and extract the liquid from inside.

But Rhann is still very thirsty, so any liquid at all is quite welcome.

He raises his head and looks up once again at the great billboard and the display and reads:

This is not a painting it’s a provocation.

It was Martha, his ex-girlfriend, man was she tough, that had shown him that image, that phrase. Everything is a provocation, he thinks.

He shuts his eyes and there, once again, is that first word:

J E S U S

Then he reads the whole sentence

IF JESUS CAME BACK TO EARTH HE’D BE DRINKING... COCACOLA.

Rhann smiles: it’s an advert, he thinks.

He shuts his eyes again. He has gone mad; his eyes no longer see, they invent.

My eyes, they invent things, he says to himself, as if he were in a doctor’s office with the ophthalmologist, and as if, reading off a chalkboard with letters in various sizes, he were getting it all wrong.

I can see the G very clearly, but the letters below it, they’re far too small, I can’t see any of them anymore, Rhann says to the ophthalmologist.

My eyes no longer see, they invent, he repeats, and in doing so, he appears to be asking forgiveness for being almost blind. Rhann shudders, but now at last he senses a human hand on his body, and can hear now, yes, quite clearly, words coming from somewhere outside of him.

“Rhann is getting delirious, his fever won’t go down.”

He feels relieved: it’s just a fever, he whispers. He tries to figure out who had been speaking, had it been Martha, or his wife? It must have been his wife, surely; she was one of those pieces of homework his father had given him. Rhann is delirious, certainly, but he has not forgotten that.

Freud is dead, but with Rhann he must have made an exception, since here he is, Freud that is, right beside of him, and he has brought along a couple of his dogs. Rhann asks him what the dogs’ names are.

1, and 2, Freud replies.

Those are numbers, not names!, Rhann screams – but Freud has already disappeared.

Rhann imagines Freud addressing his dogs as 1 and 2, addressing them as numbers. That’s brutal, he thinks. Dogs, they deserve to have names.

“Rhann is delirious,” he hears again, “his fever won’t go down.”

“PERFORMING THE EXHIBITION # 1” in the section Word of the exhibition “REHEARSAL FOR A COMMUNITY – Portrait of a collection under construction (take 1)”. Photo: Paulo Mendes Archive Studio.

|

|

“PERFORMING THE EXHIBITION # 1” in the section Sound of the exhibition “REHEARSAL FOR A COMMUNITY – Portrait of a collection under construction (take 1)”. Photos: Francisco Craveiro (By Agency), courtesy of EDP Foundation / maat, and Paulo Mendes Archive Studio.

3 – Martha and sound

We are in 2012 and Martha takes pleasure in the sound of a cello, even when it has been left standing on the floor with no one around to play it because Martha knows that there is such a sound that is produced by the form of things, that the shape of the cello conjures its sound as a phantom, a phantom in her brain, her memory, which ticks away furiously inside her skull, just as it would in some fanatic musician, given just two more minutes to live, just two more minutes in which to play his instrument. Some musicians would doubtless go mad if there were a limit on how much time they had left in which to play and would, like enough, acquire an abrupt keenness in their hands and their fingers and their thoughts and would start playing the notes of a thing more quickly, as if the little time they had left obliged them to skew, with quickness, those ancient and languid classical compositions.

And Martha thought that a truly wise musician would be precisely that which, given just two more minutes of living consciousness in which to play on the cello, would play – in a measured, simple way – a melody they admired, without speeding anything up or getting out of time. The man who remains patient even on the verge of death, that’s what a wise man is, Martha thinks.

Martha, some years before, in 2009, had had a photograph taken with a girlfriend and a couple of her guy friends, and the four of them back then had had common hopes, but now three years have gone by, and everything has changed. A photo cannot capture the internal movement of a person; the living are always going from one place to another; and she, three years later, is no longer there beside her friends; she never even thought to give them a call; she was mute as far as they were concerned, and they were deaf as far as she was. Not even Rhann, to whom she had been closest. And closest because he hated his father as much as she did. And this is something that has always brought together strangers and crazy people.

Joshua, Martha’s father, had been both her father and a madman, which had made him more of a madman than a father.

But right now she is thinking about Rhann. Nothing major had transpired to justify the distance that had grown between the two of them – just life, just time, and boredom. They bored her, those friends in the photo, and few greater barriers exist than tedium to sustained friendliness between human beings. You’re so boring, you deserve to die, Martha thinks, and laughs to herself, all alone. Rhann deserved to die. He was very boring, and married.

And Martha ponders, now, on the strangeness of the sensation one feels on hearing the sound of the telephone while looking closely at a photograph, just as she was then. The phone keeps ringing, and the photo of the four friends remains in her hands.

A photograph with people in it, frozen there in silver print, silent and stock-still. The phone does a lot more talking than they do, Martha thinks.

Martha picks up, it’s her brother, Kross; a bum. The way he speaks he sounds just like their father. He seems pleased, something about a job in a hotel. Martha puts the phone down. He’s a waster, she thinks, and suddenly feels the urge to start dancing.

It was he, Kross that is, who ended up with their father’s knife, Martha knows this, and at that moment, she thinks to herself: and may he make good use of it. The knife that belongs to the father is passed down to the son. The daughter is always something else entirely. Merely a witness, it seems. Someone who came into the world just to observe.

But Martha lay her focus again on the photograph of her friends, and there was Rhann, the man she used to love. And she was struck by the impression then that the sound in her life at that exact moment was being arbitrarily inserted, without her willing it, into the photographs in front of her – as a sort of soundtrack to the pictures. The sounds of the present, inhabiting these old images. And though perhaps it was not the case, she did feel as if the sounds were more alive, and far more potent, than the images themselves.

And this, Martha tended to think, was why she had to choose her sounds carefully, both those for her house and those for her life in general, since these sounds were the sounds that allowed photographs like that of her father, long dead, to speak again, that spoke also for this mute photograph in front of her, for those three friends she had not hung out with in so long.

One must pick the right sounds, Martha insisted, and this was why, often to her own surprise, she would find herself putting on a video of a death penalty execution by electric chair. And she would shut up and watch. Would listen closely to each individual sound, like a detective: the sounds associated with the preparation, the sound of hands being tied down and of hands doing the tying, and then, next, that sound like a mosquito trembling, the timid sound of an electric current that seems to want to avoid making too much noise, as not to scare anybody overly much; and yet afterwards, a series of sounds coming from where exactly it was hard to tell, the chair, or the condemned individual – an awful medley of the electrical and the human.

A body that has absorbed an excess of electricity takes on a more lucid, luminous form, Martha would think to herself – then straight away feel appalled by what she had just thought.

But then Martha would close her eyes and keep listening to the sounds, like someone listening to some macabre modern symphony. And she would think about Joshua, her father.

“PERFORMING THE EXHIBITION # 1” in the section Laziness of the exhibition “REHEARSAL FOR A COMMUNITY – Portrait of a collection under construction (take 1)”. Photo: Francisco Craveiro (By Agency), courtesy of EDP Foundation / maat.

4 – Kross and laziness

We are in 2020 and Kross is lifting his arms above his head and casting a figure with his shadow. It looks like he is doing ballet, albeit alone, and without music.

This year is a year in which humans have been turned into shadows. Remote, bodiless. Sombre things, drifting across the floor and along the walls, distancing themselves from the nuisance of other living beings.

His shadow can touch everything, and everybody; a healthy shadow, Kross thinks, and laughs.

And there it is: he pictures his shadow touching upon his mother’s dying face; and touching it without the doctors noticing. For touching means going to prison.

My shadow can visit my mother, Kross thinks, and starts laughing again. Then he stops quite abruptly and thinks: I cannot visit my father because he is mad and because he is dead. He has been mad a very long time, and dead a very long time also.

Kross suddenly stands up and grabs an empty packet of Marlboro cigarettes and puts all the gold his mother gave him inside of it. Sure, it does not amount to much. A pack of Marlboro is big enough. Weekend, rest. Weekdays, rest. The great and troubled rest that is unemployment.

“PERFORMING THE EXHIBITION # 1” in the section Laziness of the exhibition “REHEARSAL FOR A COMMUNITY – Portrait of a collection under construction (take 1)”. Photos: Paulo Mendes Archive Studio.

“PERFORMING THE EXHIBITION # 1” in the section Laziness of the exhibition “REHEARSAL FOR A COMMUNITY – Portrait of a collection under construction (take 1)”. Photo: Paulo Mendes Archive Studio.

A few months earlier, Kross had been in what he considered to be the vital post of resident door-knob turner; he would open doors in order so that others might pass through them, and approached said task as if it were an act of delicate engineering (comprised of minute actions of the wrist and several muscles too small to name); and without the use of any technical equipment, and without making a single sound, he would unbar the way for young ladies and their overlords to pass on through.

No clamp or fine instrument can rival human delicateness, and in Kross, this delicateness was a professional, salary-earning quality; he opened the doors of the hotel from 9 in the morning until 5 in the afternoon, and this was no problem, his right hand was as dexterous as a professional tennis player’s; as for his left, he made use of it only when a certain disequilibrium arising from his position by the side of the door demanded it. But rarely did such a thing ever happen.

So back then laziness was only the intermediary for a gap in human traffic (the hotel did seem like a sort of city, if one composed solely of pedestrian routes). Yes, there it had been, the enormous hotel, sometimes with bottlenecks forming near the lifts that gave access to the hotel’s many stories, with each ascent and halt announcing better views of the sky.

A form of idle laziness exercised with the whole body, and not merely in that precise rotation of the wrist. Kross was resting – resting with his head, his hips, his arse, his back, his legs, and his ankles, all of them lain out across the sofa in the hotel bar; it was morning and empty, and empty on account of all the wine last night, which had meant its partying, rumpus-inclined patrons had not got themselves into bed until late.

And yes, downstairs there were the games tables, a casino which never let anyone leave as rich as when they came in.

But now this, a catastrophe: the hotel-doors shut, 2020, mad year, and Kross unemployed, all by himself, lifting his arms up above his head and casting shadows upon the wall.

All of a sudden, he stops messing around with his shadow and picks up a knife. It was Joshua, his mad father, who had left it there. Not there, as in, in that particular place, but there, in Kross’ existence. Perhaps now was the time to start taking notice. Of the knife, and of his father.

What should he do, all alone with a knife and his despair? He can think of two things but determines to do just one of them – if only because doing that one first would preclude his doing the other.

The knife is there, my father was a madman, Kross thinks, he would howl at midday, they said. Would go out at night and howl like a wolf.

It is eleven-thirty – Kross sits down and decides to wait a little longer. At noon it will be the hour. He is tired, he shuts his eyes, he sits idle – but he’ll wake up on time.

Translated by Vita Dervan.

“PERFORMING THE EXHIBITION # 1” in the section Laziness. Photo: Paulo Mendes Archive Studio.

“PERFORMING THE EXHIBITION # 1” in the section Laziness. Photo: Paulo Mendes Archive Studio.

Writer, novelist, playwright, poet and critic, Gonçalo M. Tavares was born in Luanda and teaches Theory of Science in Lisbon, where he lives. In 2005, with “Jerusalém” he won the José Saramago Prize for young writers. His novel “Aprender a rezar na era da técnica” has received the prestigious Prize of the Best Foreign Book 2010 in France. This book was also won the Special Prize of the Jury of the Le Grand Prix Littéraire du Web Cultura 2010. Gonçalo M. Tavares’ work has been published in almost 50 countries.

Gonçalo M. Tavares and José Valente were asked by Paulo Mendes, curator of the exhibition REHEARSAL FOR A COMMUNITY – Portrait of a collection under construction (take 1), to iconoclastically appropriate the works featured in the exhibition, which covers a historical period of collective memory from 1942 to the present. The manner in which these fictions of word and sound add new interpretations to the interpretation of exhibited works, and the manner in which text and music can merge into a single work, were critical parts of the work process.

In 2021, maat inaugurated a new programme around the EDP Foundation collections. Both collections — Portuguese Art and Energy Heritage — are regularly presented within the spaces of Central through an invitational series of curatorial projects by diverse experts, researchers and thinkers that are intended to engage with this reservoir of knowledge from multiple intellectual vantage points. By providing alternative conceptual and scholarly interpretations, the programme aims to bring forward new readings to enlighten historical, social and technological narratives that go beyond those of the collection itself.

The EDP Foundation Portuguese Art Collection was started in 2000 with the aim of encompassing several generations of contemporary Portuguese artists, as well as assorted expressions of artistic creation such as painting, photography, video and installation. Continuously evolving with yearly acquisitions, the collection comprises approximately 2,400 works by more than 330 artists.