Mono Voices: My Recent History

João Pimenta Gomes

I started thinking about mono when I was 16 after seeing a picture of a hi-fi system in a room. At the centre of it was a big speaker that was connected to an amplifier which was pointed to a chair. There was no caption, and I had absolutely no idea which sort of equipment it was; however, it was entirely different from anything I'd ever seen up until then. I didn't get why there was only one speaker.

I grew up listening to music on my beloved Japanese hi-fi system, which had been given to me years earlier. The love I felt for my records was amplified at every inch between myself and the speakers. The air between my body and the speakers was an instrument in itself, and the walls echoed the imaginary the album cover, the booklet, with info about the recording, and the pictures of the musicians created throughout my teenage years in my room. That was my entire world, with my records and my stereo. I love all the music I listened to on my headphones the same.

Up until that time, listening to the stereo mix of "Drive My Car" on my headphones seemed natural to me—a very daring, audacious creative decision, I thought. When compared with all the stereo music made from the 1970s on, that hard panning, with the guitars on one side and the voices on the other, made me fantasise about a studio recording process that was entirely dissociated from some attempt to replicate the image of the band as an organism arranged on stage. Rendering the studio record a place that comes from one's imagination and belongs to the fantasy realm educated me about the possibilities of the album and of recording as a boundless creative power.

For me, there was no separation between the stereo of Electric Ladyland and that of Rubber Soul, or that of The Piper at the Gates of Dawn: they were all part of a set of records made by musicians and sound technicians who were seeking to make the most of the bustling technological evolution that was taking place at the time.

The first two tracks of Electric Ladyland are my favourite moment in any record I've ever listened to. I can't tell whether what has influenced me the most are the songs in themselves or the impact of listening to all those high-frequency sounds travelling through my head on the headphones, of grasping through Jimi Hendrix and Eddie Kramer the power of using this sonic trash to create new instruments divorced from any graphic relationship with the set of instruments we usually associate with a rock trio.

I found out later that The Beatles only worked in stereo for Abbey Road, and that their vision for their songs up until this record had been based on mono rather than stereo. This means they thought about their music not in panoramic terms but rather focussing on distance, proximity, and dilution.

Owing to its open-source nature, the Eurorack modular synth allows me to explore and amplify these sonic matters. The relationships between recording, composition, and its reproduction make up the bulk of my studio work. My daily work process focusses on bringing together and manipulating recordings I've made myself, and can easily be associated with the processes employed in musique concrète, where the tape recorder is the main source of sound. Indeed, Joe Meek, Eddie Kramer, or Roy Thomas Baker are closer to my heart.

I felt the need to restrict the sounds I use, to set the basis for exploring a number of possibilities generated by the human voice. 1950s and '60s vocal groups used the voice in a very creative way – the voice as an instrument that unfolds into various functions. The song's lead it was, but it also played a remarkably harmonic and rhythmic role.

I recorded Carminho singing each note of a microtonal scale and then broke them down individually, which got me a new source of sound. By unfolding this idea of a musical instrument that transforms from its original function into a song (for example, going from a melodic function to a harmonic or strictly rhythmic one), I'm able to explore new composition possibilities that rest on a fixed, recorded basis.

My current musical thought is entirely guided by my mixing desk's 16 channels. In order to have more than 16 instruments in a song, I have to bounce them. This is a destructive process, since those 16 tracks become one and then you can't access any of them anymore.

I see this part of the process as a collection, something that will be used later. A final piece is the fruit of several "collections."

Poly-Free (2022) carries on my desire to make music in which the synth and its connections, the speaker, the air, and the tape recorder are one.

|

João Pimenta Gomes (Lisbon, 1989) is a visual artist and musician that lives and works in Lisbon. In his artistic practice, he addresses references mostly related to music and explores the relationships between space and body through by manipulating modular synthesisers, images and objects, enabling encounters between the analogue and the digital, the sensory and the conceptual. His most notable exhibitions include Clouds (Kunstraum Botschaft, Berlin, 2021), Trabalho de Inverno (Galeria Quadrado Azul, Lisbon, 2021), as member of the group Matéria Simples, with whom he also held A Ilha de Calipso (Appleton Garagem, Lisbon, 2020), and Micro Ressonâncias (Appleton Box, Lisbon, 2020).

|

|

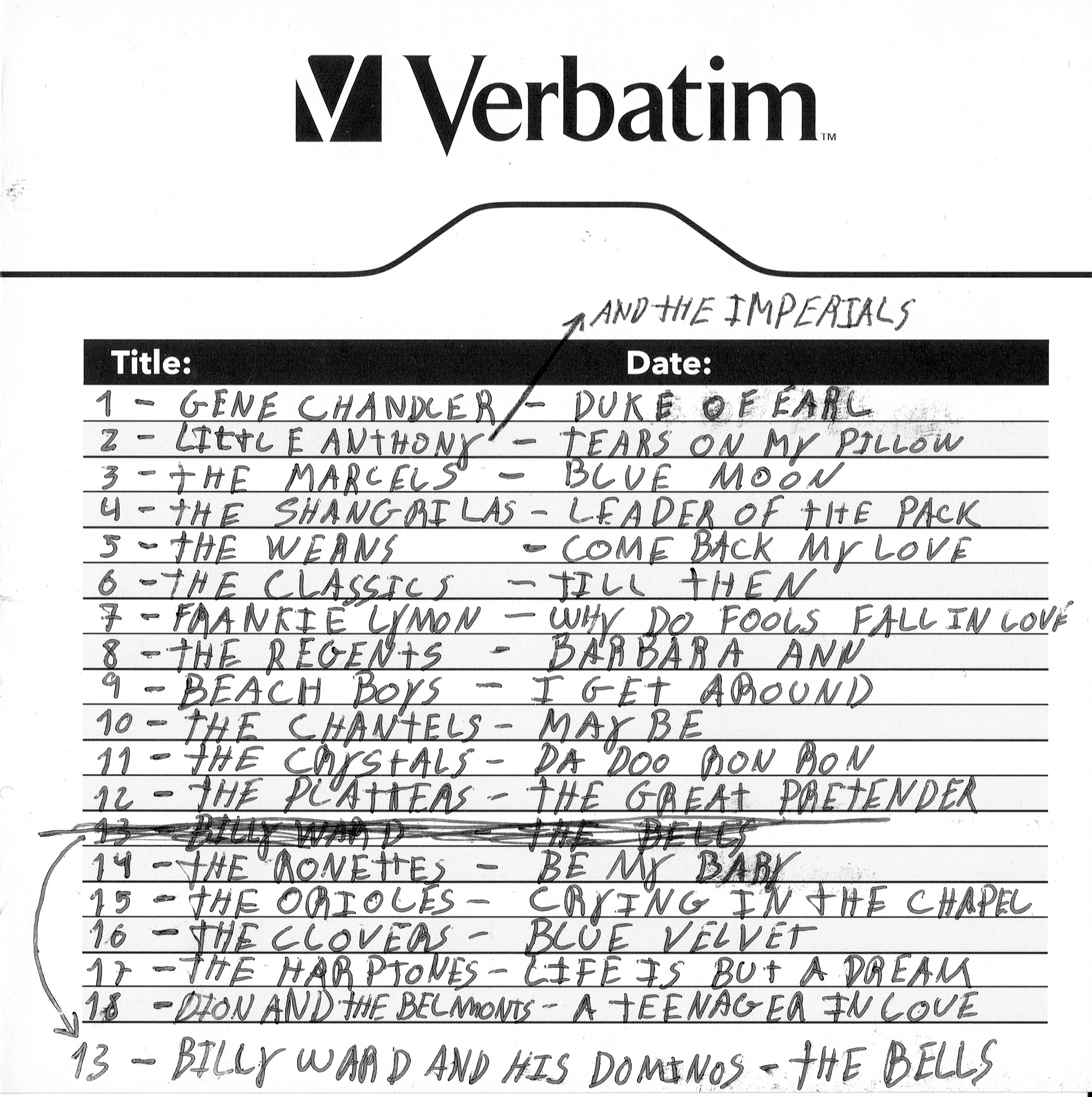

The “Doo Woop” playlist by João Pimenta Gomes for maat, in the context of his exhibition Poly-Free at Gabinete (maat, 29/04–20/06/2022).

1 - Gene Chandler, "Duke of Earl"

2 - Little Anthony and the Imperials, "Tears on My Pillow"

3 - The Marcels, "Blue Moon"

4 - The Shangri-Las, "Leader of the Pack"

5 - The Wrens, "Come Back My Love"

6 - The Classics, "Till Then"

7 - Frankie Lymon, "Why do Fools Fall in Love"

8 - The Regents, "Barbara Ann"

9 - Beach Boys, "I Get Around"

10 - The Chantels, "Maybe"

11 - The Crystals, "Da Doo Ron Ron"

12 - The Platters, "The Great Pretender"

13 - Billy Ward and His Dominoes, "The Bells"

14 - The Ronettes, "Be my Baby"

15 - The Orioles, "Crying in the Chapel"

16 - The Clovers, "Blue Velvet"

17 - The Harptones, "Life Is But a Dream"

18 - Dion and the Belmonts, "A Teenager in Love"

|

In Poly-Free (2022), João Pimenta Gomes explores the relationships between space and music, and between recording, composing and reproducing, emphasising the latter as a key element in this new work. The idea of the physical sound speaker is revived, embodying it through an object. To it, Pimenta Gomes adds an original sound composition produced in a new instrument, created by him – baptised as Metavox, a modular synthesizer designed to play only human voice samples. Poly-Free is the second show in the series Gabinete (maat, 29/04–20/06/2022), curated by João Pinharanda.

|

Gabinete (or Cabinet) reinstates the original name of a room at Central Tejo, now with the function of a new space at maat for the exhibition of small nuclei of works by Portuguese artists. Programmed by João Pinharanda, maat director.

|