|

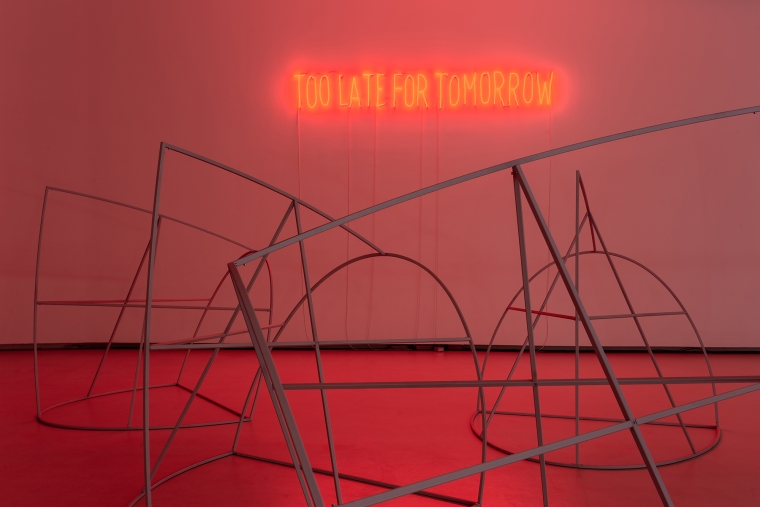

View of maat’s Oval Gallery with EXIST/RESIST. Works by Didier Fiúza Faustino (1995–2022) (maat, 05/10/2022-06/03/2023). Courtesy of the artist and EDP Foundation / maat. Photo: Pedro Pina. |

|

The Work of Didier Fiúza Faustino

A conversation with Pelin Tan, curator of the exhibition EXIST/RESIST. Works by Didier Fiúza Faustino (1995-2022)

|

How, when and where did you first encounter Didier Fiúza Faustino’s work and thinking? And, is this the first time you two have worked together on a show?

|

Our first encounter was at the Bordeaux Biennial in 2009 where I was invited by him and his team to participate in a panel on urban conflict and hospitality. It was a fruitful intervention at the biennial, where we had a chance to have a debate around multicultural urban spaces, diverse communities and how living together is possible in such contexts – what are the radical democratic possibilities. In Didier’s practice, the questions of community, scale, bodies are always intertwined with the basics of design and art. This brings up not only his position around imagining and producing forms of design and art, but also a provocation of the regimes of representation in his practice.

|

|

EXIST/RESIST is the first institutional exhibition surveying more than twenty-five years of Didier’s practice. Why now and what does the project aim to contribute?

|

After sharing many moments over the past years, we started to reflect on the show not in terms of the sum of his works, but around what is a provocative and futuristic form of design and art that can reveal the social norms describing the body and its definition in society and urban space. Didier has been working around these themes since the 1990s – a sociological and philosophical topic that pops up all the time in everyday life, from war to migration to urban resistance, to Covid conditions. The design and artistic practice of Didier is almost symptomatic and runs in parallel to social, political and ecological conditions. Moreover, the rich variety of materials and mediums that he employs also clearly indicate his critical questioning of the architectural profession and the role of the architect. I do aim to present these efforts, make them accessible for various audiences.

|

|

And how did you approach this survey as a curator? How do you present his body of work and what argument(s) do you try to build with the show?

|

In any “retrospective” exhibition, the architect/artist gets stressed about what to include and what to exclude. There is also the question of a certain style of retrospective exhibition, especially of architecture in the twentieth century. Even the scenography of such exhibitions is similar. We were thinking more about what works are significant and create clusters that support a certain connection. First, there is the play between the border of design and artistic provocation and second, the ongoing theme about public space and radical democracy. My aim was to bring together the various fluxes of scale and material, and iconic works that signify a timeless concern for the sociology of everyday life, both within the public and domestic spheres.

|

|

In your essay you write about Didier’s work “tuning between architectural desire and the borders of design”. Can you expand on that? What have you found in Didier’s personal archive and brought into the show?

|

In my essay I try to make two layered discussions: first on Didier’s take on body/bodies and the social norms surrounding it and its boundaries with design. The second is the discussion around the concept of form, referring to the deconstructions by Gordon Matta-Clark in late twentieth- century architectural history. I think both are intertwined. That enables us to discuss Didier’s approach on architectural or design form in any scale in a more framed and discursive way that matters in the actual design practice in general. In the last twenty years, there has been more criticism by younger generations of architects and designers on the boundaries of design, the normative practice of architecture that influence pedagogical practice, as well as the market. We are in an era that is rethinking what architecture and design mean, how they function in our everyday life while we deal with diffuse social and climate catastrophes. From that perspective, I see Didier’s practice as an in-between tension of desire and the thick boundaries formed within norms. His effort in deconstructing it and giving more space to desire is also a Spinozian philosophy that reveals itself in action and existence in his works. The clash between desire, body and norms is a triangle in our everyday life that shifts between modernism and animism. Design could be a tool to reveal this, architecture could be the medium to convey the discourse. This is what Didier’s work does.

|

|

What have you found in Didier’s personal archive and brought into the show?

|

Didier as an architect and thinker absorbs from many sources for his intellectual creation. Primarily, novels of alternative literature about futurism and gender, philosophical texts, visual diaries, recordings in Africa, in China, which are testament to his curiosity for culture, especially non-Western culture and non-Western knowledge, from built environment to food. Music is also one of the sources of inspiration – sound and spaces connect for Didier. Practitioners like Matta-Clark are an inspiration to think differently about form and presentation originating in Western modernity. All artefacts that relate to urban sub-cultures are primal objects for his process of creation. In this show we see the research process of the architect as the living archive, potentially inspiring young designers and architects by revealing Didier’s hidden working practices.

|

|

What is your favourite work or statement in the show and why?

|

This is a difficult question to answer. I believe each work has its own aura, provocation of ideas, way of research, proposal of material and invitation to engage. I have many favourite works and the first one is My First House (1996) – Didier’s first built house. The children on the street ask Didier if he is an architect, and he says yes, and the children invite him to help build their house from a tent. And Didier does so for them. The existing photo is the visual evidence of this act and work. There is no real home. There is no real built architecture. I do like the little story behind this work, and I still see this story as a vital dilemma in architecture and in the profession. Furthermore, Democracia Portátil (2016) is also what we could call a small-scale public space where the audience and citizens are invited into an intimate discussion about contemporary urgent topics. This work is also one that connects with many other works of his in various moments of his career, where he focusses on the practice of radical democracy and co-existence in public space. Too late for Tomorrow (2022) the very last work produced for this show, is for me important in two ways: firstly it connects the survival, resistance, existence questions around dwelling and shelter to his first work in 1996. Secondly, it creates a public space that as a socially-engaged work the audience can experience and intervene in by using them. We are hoping this work will create an intimate co-existence of a minor publicness in the museum space and provide a comfort zone for the audience.

|

|

It would be great to have your take on Didier’s profile, apropos the hyphenated architect. How do you describe Didier’s practice or “Haltung”?

|

I think Didier is an architect who is in constant denial of the architecture profession and mainstream-defined modern Western design. By not stepping outside the realm of architecture, he insists on queering knowledge and deconstructs norms. I think as a designer and pedagogue he is also a provocateur in relation to the set knowledge and institutional framework of architecture as a discipline and profession. But I would not either marginalise him so that mainstream architecture practice could be safe. In contrast, this is how design and architecture should be reformed in the present and in the future of everyday life.

|

|

Pelin Tan is a sociologist and art historian based in Turkey, a professor at Batman University (Turkey), a senior researcher at the Center for Arts, Design and Social Research (Boston), and researcher at the Department of Architecture, School of Engineering, Thessaly University (Greece, 2021–2026). She is involved in Urgent Pedagogies by IASPIS (Stockholm) and Cosmological Gardens: Land, Cultivation, Care by CAD+SR (Spoleto). Tan has curated Gardentopia – Matera 2019 (Italy), and was an associate curator of Adhocracy – 1st Istanbul Design Biennial (2015) and co-curated, with Liam Gillick, the I-DEA Archive by Matera Foundation. She is currently working on her book on Emmanuel Levinas and spatiality/architecture and phenomenology.

|

EXIST/RESIST (maat, 05/10/2022-06/03/2023) is the first institutional exhibition surveying almost thirty years of practice of Didier Fiúza Faustino, the French-Portuguese experimentalist whose work has consistently provoked and transgressed the formal and conceptual demarcations between architecture, design and art. Curated by Pelin Tan, the exhibition brings together for the first time a vast selection of works, preparatory materials, and prototypes – drawings, photos, models, large-scale installations, films, and objects, revolving around four core strands of research that recur in Faustino’s work: “Housing and Dwelling”, “Borders of Bodies”, “Design as Resistance”, “Agonism in Public Space”. Featuring both past and newly created pieces, loans from international collections and never-seen-before documentation from the artist-architect’s private archive, the show is set in a scenography designed by Faustino’s studio – Mésarchitecture, and conceptually devised to put in dialogue two core areas of the museum and thus create two distinctive spatial experiences.

|