Script for an (imagined) tour of the exhibition EXIST/RESIST – Works by Didier Fiúza Faustino: 1995–2022

Susana Ventura

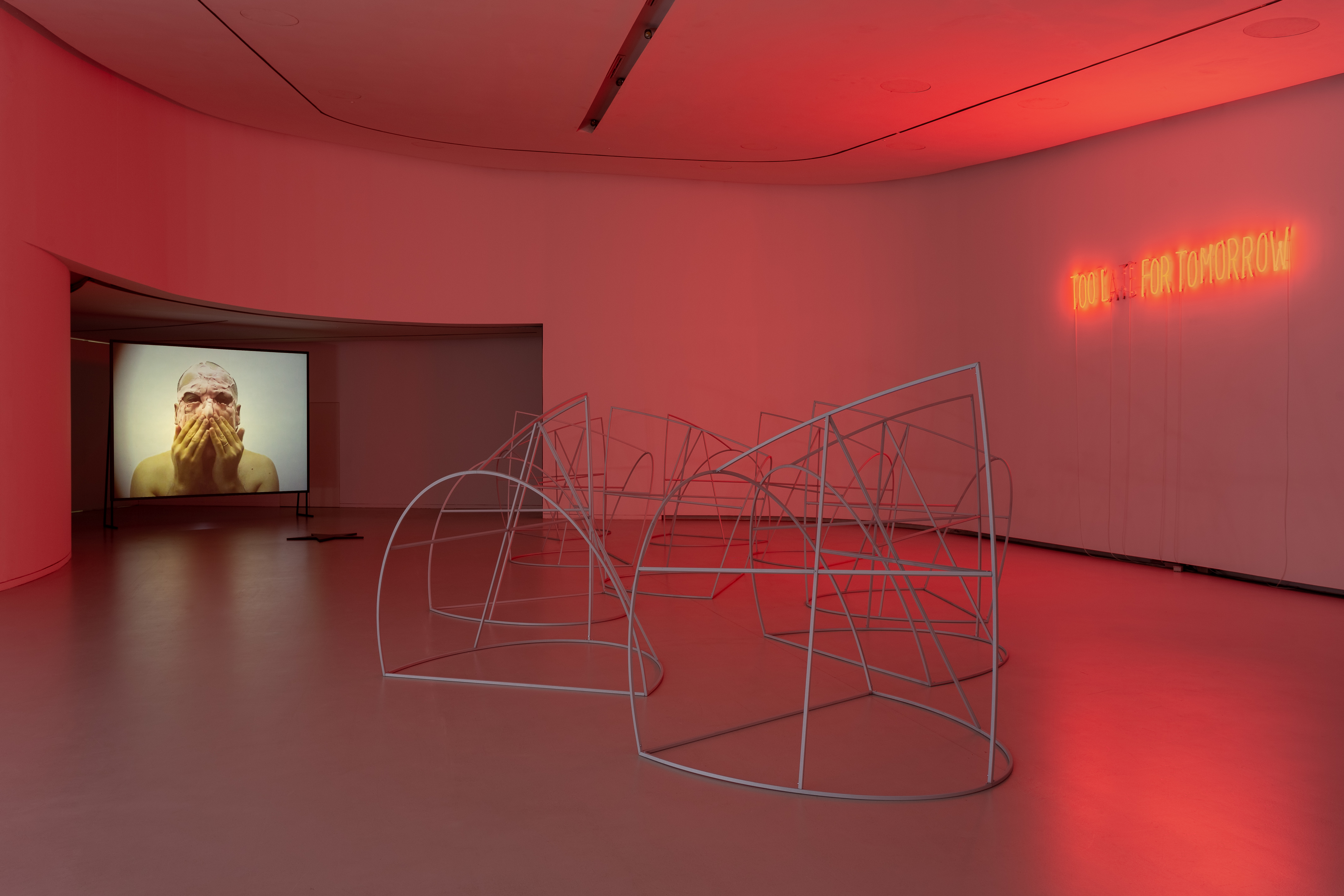

View of the exhibition EXIST/RESIST – Works by Didier Fiúza Faustino: 1995–2022 (maat, Lisbon, 05/10/2022–06/03/2023). Photo: Bruno Lopes, courtesy of EDP Foundation / maat.

The following script is for a guided tour of the exhibition EXIST/RESIST – Works by Didier Fiúza Faustino: 1995–2022, curated by Pelin Tan, which ran at maat – Museum of Art, Architecture and Technology, in Lisbon, from 05/10/2022 to 06/03/2023; it is based on a conversation in movement between Didier Fiúza Faustino and Susana Ventura held in 10/12/2022, in which the two guide the public in a critical selection of different works and in the always latent and pulsating binomial of action and thought in the exhibition, seeking to evidence the presence of the body and its transformation (and utilisation) as a guerrilla warfare space, while also taking into consideration the, at times, tense relations between the individual body and the collective body. Inevitably, the body is understood as a space, and the space as a body, where the exchanges between the two give rise to a conflict that either leads them to an undesirable rupture or to new positions and exchanges of power between the two.

“Everything that has to do with the body, that manifests itself as transparent or seductive or threatening, becomes an irreversible sign of a power that changes but still persists in its multiple incarnations. With Michel Foucault we seem to have a clearer view of the totalitarian practices of powers that, from case to case, establish themselves in the context of human bodies and the degree to which those powers, however coercive and apparently all-power-ful they may be, always encounter opposition of one sort or another that reduce them almost to a condition of powerlessness. It is precisely in the bodies, from whose disciplinary organisation the powers take their very legitimacy, that this conflict takes place”. (→ 1)

-

(1) Francesca Alfano Miglietti, Extreme Bodies: The Use and Abuse of the Body in Art. Milan: Skira, 2003, 15.

View of the exhibition EXIST/RESIST – Works by Didier Fiúza Faustino: 1995–2022 (maat, Lisbon, 05/10/2022–06/03/2023). Photo: Bruno Lopes, courtesy of EDP Foundation / maat.

The body is simultaneously the privileged space and the instrument for the exercise of power in both senses: the body contains and exercises power(s) as much as it subjects itself to it/them. Traumas, wounds, pain are experienced through the body, as are joy, hope and desire.

The body, almost always involuntarily, is subjected to violent processes that may torment or break it and can also lead to death. But it is also home to the immense power that is revolt, fight and rupture. One of the archetypes of power systems, as classified by Foucault, is architecture, because of the control it has over the body. This is not just the case in the fundamental example of Jeremy Bentham’s Panopticon (1785), where the circular structure allowed for the total control and surveillance of the bodies (a model applied above all to prisons and hospitals (→ 2)), but also in the design of a family home, where gestures, movements and actions are inscribed in the architectural composition, which conditions and forces the bodies to carry out certain tasks, imbued in the centuries-old normativity that is precisely demanded by, and practised by, architecture. Architecture demands of the bodies a behavioural response that corresponds to a sign (returning again to Foucault), which represents the subject and the action or the subject and the object in a universal code built on the basis of an ideal body.

-

(2) Curiously enough, one can consider that the circular structure model is often adopted by state assemblies or parliaments, as is the case in its maximum expression – as a complete and total circle, as in Bentham’s model – in the Jonas Staal-designed parliament building for the stateless government of the Autonomous Region of Rojava (in northern Syria, after separation of this Kurdish region from the Assad regime), where the circular form is meant to represent to values of the region (federalism, gender equality and communalism). In this case, the ideology alters the form’s meaning, above all when the centre is removed from the form (the centre as a symbol of power).

“Each society applies different forms of relations of power that create norms, which refer to the domination of behaviours on others. We cannot exit them, but we can transgress them in order to reduce these relations of dominations in the best way we can. In other words, if we conceive a table or a chair in the same way than we usually think of it, we would need to choose at which height we should place it. In this regard, whatever our decision will be, it will contribute a certain norm. However, this norm can be different from the one of the political milieu in which we live, and it can also vary within a same building rather than imposing an absolute standard. The body that we consider to conceive an architecture should not be a fantasy, it should be incarnated. Just like architecture – often too disincarnated by architects too – the body is an assemblage of matter in movement that composes relations with its environment. When this environment is built in such a way that these relations are thought in their most harmonious dimension rather the most normalized one, we can talk of an act veritably political since it complexities [sic] and transforms the relations of power within this society”. (→ 3)

-

(3) Léopold Lambert, “Topie impitoyable: transgressing the normalized ideal body for traces”. In https://thefunambulist.net/editorials/topie-impitoyable-transgressing-the-normalized-ideal-body-for-traces. Last visited on 2 February 2023.

The body as a space of guerrilla warfare exposes conflict situations in which both the body and the space are expected to challenge the norms, thus experimenting with forms of transgression and subversion or, as Didier Fiúza Faustino highlights, experimenting its condition of fragility, without fear of transitoriness, precariousness or instability. In the end, how can these characteristics be converted into forms of power in architecture?

The desire is that this script will provide any person with the unique knowledge resulting from the conversation and that the voices, which are now indistinct, can accompany the imagination in a tour of the exhibition or make that tour possible through thought itself.

Script

Written on the basis of a recording of a conversation in movement between Didier Fiúza Faustino and Susana Ventura, recorded on 10 December 2022 at maat.

View of the exhibition EXIST/RESIST – Works by Didier Fiúza Faustino: 1995–2022 (maat, Lisbon, 05/10/2022–06/03/2023). Photo: Bruno Lopes, courtesy of EDP Foundation / maat.

1. (G)host in the (S)hell (2008)

In the video, a head chews pieces of pink chewing gum. It shapes them with saliva and places them one by one on its own face. The face slowly disappears, giving rise to another being behind the monstruous mask.

Voice 01

(In front of the video)

This piece was produced for an exhibition at the Gabrielle Maubrie Gallery in Paris on masks, where the gallery owner asked several artists and architects to create what could be a contemporary mask or a vision of what a mask is. For this reason, it was of interest to question what a mask could reveal or conceal, considering that it is a representation that can have symbolic, social or magical functions, amongst other and very different things. In the case of an architect, what can be questioned by means of construction of a mask? How can a mask be a representation of a system of territorial, social, cultural or political (as architecture is) relations, acting, as it does, on the boundary between the identity of the individual (the architect) and their representation in the public space (the architectural work)?

Voice 02

(In front of the video)

The mask is a medium that acts between the two planes, which albeit are made up of many folds. The architect’s face may be the representation of his/her dreams and desires, as well as his/her anxieties and frustrations, while his/her public face will find it difficult to escape the harshness of the conditions and contexts he/she acts in. In the mask, a magical operation takes place. As Sophia de Mello Breyner Andresen would put it: “The mask is the way in which someone says how he/she is”. One thinks that the mask hides, that it conceals the real identity of the wearer. In reality, it shows the points of tension a face is constructed on. While one may think that body and space form an inseparable block, this video reveals both the architect and the architecture that the architect creates. However, the game of architecture (the chewing gum also evokes childhood) takes place in the interstices or in-between spaces, such as those that emerge between the two layers (that of the human skin and a new, hybrid layer resulting from the chewing gum combined with the saliva).

Voice 01

(Still in front of the video)

There is a transformation made possible by an ephemeral, fragile and inconsistent matter. The chewing gum, by means of the mastication, is transformed into the building material for a new, precarious, identity, giving rise to a form between monstrosity and vulnerability.

The title (G)host in the (S)hell is taken from a Japanese cyberpunk animation film from 1989, in which the female cyborg protagonist starts to question her existence, as part human, part computer code. Ten years later, the artists Philippe Parreno and Pierre Huyghe invited 13 artists to create, during a period of three years, different stories for AnnLee, an avatar they acquired from a Japanese agency that used to sell cartoon characters for commercial films, and to whom they gave her own image rights (rights to exist, in other words, to be) at the end of the artistic project No Ghost Just a Shell. In Philippe Parreno’s video, Anywhere Out of the World (2000), which was part of the project, AnnLee reveals the following about herself: “I am a product. A product freed from the marketplace I was supposed to fill... I was bought but strangely enough, I do not belong to anybody. I belong to whomever is able to fill me with any kind of imaginary material anywhere out of the world. I am an imaginary character. I am no ghost, just a shell.”

By putting the G of Ghost and the S of Shell in brackets, i.e., (G)host in the (S)hell, the title opens itself up to several interpretations, leading to the inevitable question for architecture itself in its role of constructing the future: are humans ghosts who see the world as a shell during their short stay, or are they hostile, unstable guests trapped in the hell that the world reveals itself to be?

Voice 02

(Still in front of the video)

Can the future support itself on the characteristics enunciated in this work? There is a latent fragility in the imminence of the fall of the mask. But, curiously enough, said fragility is opposed by the hybrid, composite matter that creates a being that avoids all categorisation, despite the fact that it reveals itself to be monstruous. Transgression or subversion are at the root of Otherness as the creation of a form of architecture that should avoid normalisation and categorisation of the bodies (and of the spaces that are bodies).

{follow the light}

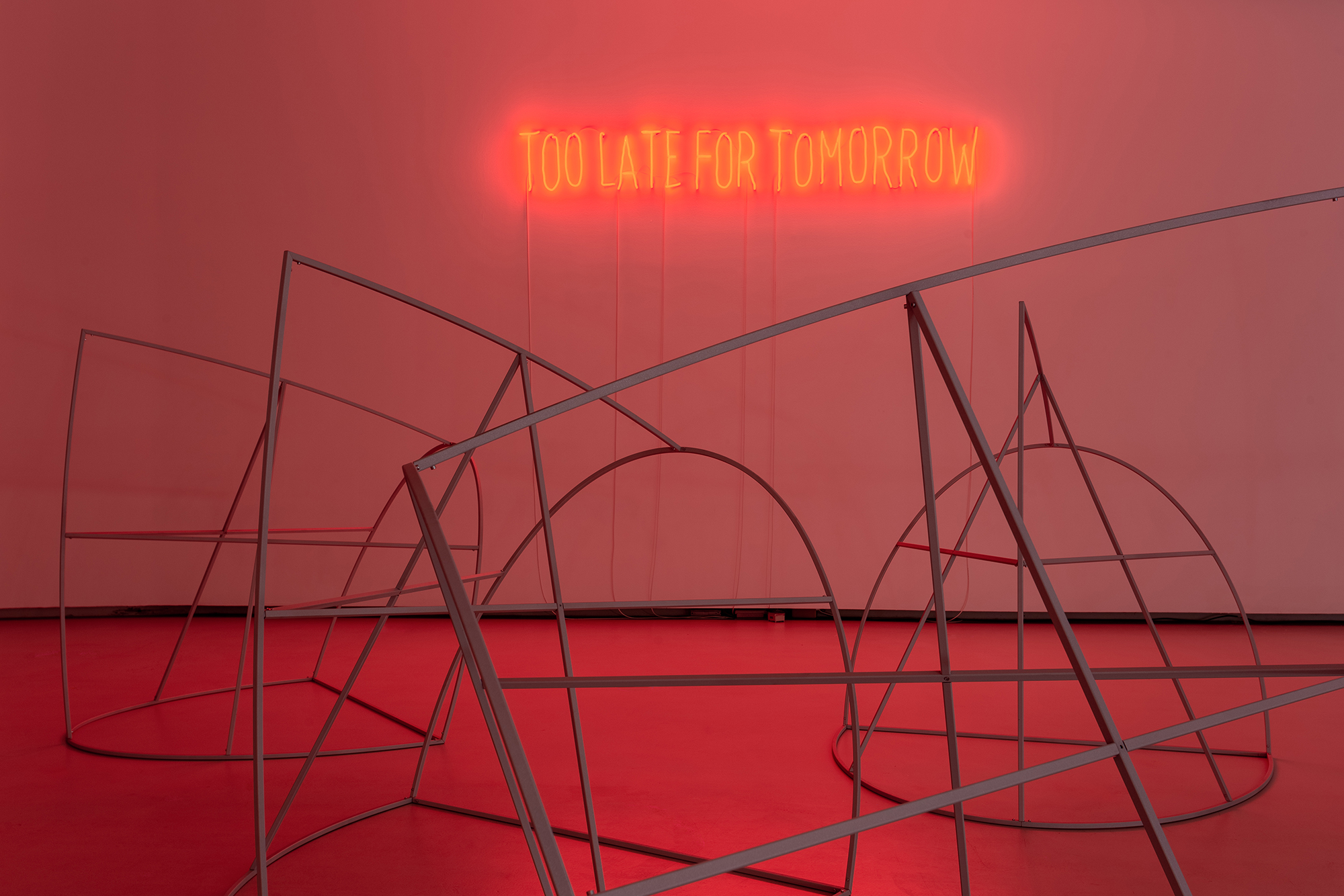

View of Mi Casa es Su Casa (2019) and Too late for Tomorrow (2022), EXIST/RESIST – Works by Didier Fiúza Faustino: 1995–2022 (maat, Lisbon, 05/10/2022–06/03/2023). Photo: Bruno Lopes, courtesy of EDP Foundation / maat.

2. Too L… for Tomorrow (2022) and Too Late for Tomorrow (2022)

On the wall a red neon light flashes on an off for Too l… for Tomorrow and Too Late for Tomorrow. The choice – the result of the undefinition generated by the two forms – is up to each visitor. Next to this work are several modular metal structures similar to an indigenous (futuristic) village, most probably from French Guyana. The visitors move between the modules, changing their position and configuration and turning them on their sides. Some opt to sit inside each module and stay there for the duration of the dialogue.

Voice 01

(From inside one of the modules, inscribed in one of its triangles)

This work starts out from a problem (in which the idea of the shell is also implicit) that habitually projects into a hypothetical future; it is, however, urgent that it be dealt with in the present: the construction of a shelter that could be transformed in accordance with the unknown, using as a driving force the context’s adversity (be it over-settlement, climatic change or unpredictable natural and human disasters, etc.).

In formal terms, the project begins with a sheet of paper and successive folds, until one has a minimal space, which rather than being a perfect ball shape, results from and in a game of angles (triangles) and curves (spheres) that cut into each other to accommodate a body. This is the first phase, where the modular structures do not yet have the skin that will eventually cover them. The piece is unfinished, just like the future.

In a second phase, as part of a performance, each of the structures receives a covering similar to the monstruous mask: a precarious, ephemeral and fragile membrane that seeks to be a response to the current lacerations currently caused by the excesses of the capitalist and neo-liberal systems.

This possibility, which is left suspended (and is also represented by the recurrent use of quotation marks and brackets for expressions that may take on multiple meanings), is a form of questioning the action of someone whose function is to produce social forms, built forms, political forms, and who instead seeks to produce hypotheses, to the extent that the form can be imbued with an openness to the undefined, thus giving itself the possibility of being something else. On the other hand, the part that is omitted can be the result of a process of abandonment of a form that is no longer but still contains a feature of the form that was… As an unfinished hypothesis, this means that the piece is still not completely disconnected from the creative act, which, accordingly, means that it can be projected to a future time and space, something that is already happening when it takes up space in an exhibition defined as prospective in contrast to the institutional reading of a retrospective.

Voice 02

(Looking at the neon light from outside one of the modules)

The idea of time, and particularly the idea of future time, is addressed in several works in the exhibition, which is regarded as a retrospective even though it is not presented in chronological order. In retrospective exhibitions, the inverse trajectory – i.e., from the future to the past – is almost always possible; in this case, this prospective space could be the end of a timeline. However, despite the selection of works produced over a continuous and extended period, there is a single time – the future – where all other times overlap or rather are dissolved in continuous folds that indiscernibly connect the future to the past, the past to the present and the present to the past.

As in the catalogue of the exhibition by Gaetano Pesce, at the Centre de Création Industrielle, Établissement Public du Centre Beaubourg, of the Musée des Arts Décoratifs, in Paris (1975), on display in one of the vitrines here: “The future is perhaps past”. Or “Future will be a Remake” as in the Möbius strip drawn by Didier Fiúza Faustino for his 2011 exhibition at the Calouste Gulbenkian Foundation’s Modern Art Centre in Lisbon. Those who play uninterruptedly – the Möbius strip connects the beginning to the end and the end to the beginning – will end up dizzy and lose all feeling for and notion of time and space, trapped in the imbalance of their own bodies.

Time is not a straight line or, if it is a line, then it takes the form of a Möbius strip connecting past, present and future without defining a beginning or an end.

The lack of definition and uncertainty caused by the neon light and fed by a number of references in the exhibition (such as, the original Star Wars filmography, Philip K. Dick’s books, a furious or anxious comic character who asks the question “Actuel?”, and the book of poster art by Barbara Kruger “No progress in pleasure”) above all serve to question time categories where the present can only be inscribed in the form of questioning and the hypotheses launched remain open; however, we know that the works of the past are also tools of tomorrow.

Despite the fact that it is an open hypothesis, the village/installation has a number of features that enable the actioning of thought on future dwelling, including on the density, scale, transmutation, proximity, the imagetic power it releases (particularly in relation to the indigenous space/body) and, above all, on the possibility of finding, of defining a public shared space, of “être ensemble”.

And where the two works can be joined, there emerges, once again, the hypothesis that the body is a tool and a vehicle that opposes the boundaries imposed by architecture if one thinks about how an ephemeral and precarious structure can make possible or agilise our questioning of the role of architecture as a builder of various futures.

{cut to:}

3. Don't Trust Architects (2011)

As one goes from the prospective space to the oval room, where the ample space is compressed for a moment before becoming wider again, one hears, in various languages: “Don’t trust architects”! The tension is unavoidable after the uncertainty launched by the neon light and the open hypothesis of the creation of a collective body through the open game of manipulation and appropriation of architectural elements.

Voice 02

(In the corridor)

This sound piece was originally complemented by another sound piece entitled Trust Me, in which 3 voices, in different languages, repeatedly proclaim: “Architecture can be an instrument for honing our senses and fine-tuning our awareness of reality, which tends to be blunted by an excess of information, self-centredness and control. Experimenting with fragility.”

Architecture is a tool of power that can, however, become one of subversion and transgression, questioning the established power structures and challenging the conditions of the bodies, whereby it reveals precisely those of fragility and instability, but also of pleasure. The idea of architecture as a social project was the main driving force behind the modern project. Unfortunately, the institutional narratives (including the museum-based ones) favoured (and, to a certain extent, still favour) the formal issues of architectural language and new material, technological and typological paradigms, extolling their aseptic and rational qualities, the same ones that could give underdeveloped communities supposed modernity. But “We have never been modern” (→ 4) and today it continues to be urgent to attend to the cracks opened by architecture that allowed itself to be instrumentalised by power (namely, colonial power).

-

(4) The title of a work by Kader Attia: We Have Never Been Modern, 2015.

Voice 01

(In the corridor)

If the mask was a self-portrait, then this piece is a kind of self-awareness mantra because it is very easy to succumb to the comfort that comes from order and power. Don’t trust architects includes the choices made by architects themselves in challenging the dominant, rooted conditions of society, generating unexpected spaces where, at times, a minimum alteration is enough, in a conventional situation, to create a configuration that is different to that instituted by the codes and to create new interactions between people.

These conditions are particularly aggravated in more vulnerable and fragile communities, such as the current Syrian and Ukrainian communities, whose languages are heard in this piece.

{cut to:}

Views of the exhibition EXIST/RESIST – Works by Didier Fiúza Faustino: 1995–2022 (maat, Lisbon, 05/10/2022–06/03/2023). Photo: Bruno Lopes, courtesy of EDP Foundation / maat.

4. Exploring Dead Buildings (2010, 2015)

In the Oval Gallery stands a modular structure, an open boîte à merveilles (wonder box) illuminated from above by a white light, with semi-hidden niches that provide moments of revelation and challenging perspectives on the categories of objects and bodies. In the centre, several works can be seen. People gather next to a device that looks somewhat like a go-kart built by children and fitted out with a metal framework/chassis to which two spotlights and a film camera are attached. Inside the discarnate car is rudimentary seating with remnants of fibres and bits of insulating tape. Hung on the module, two large photographs show two bodies using another device with a metal structure, that is similar to an expanded armature with a camera fixed more or less at the height of the eyes, which can be found inside the module. The whole is completed by two television screens broadcasting the videos of the two chapters of Exploring Dead Buildings.

Dramatic music

Vittorio Garatti (off screen [O.S.])

It’s a dramatic future.

Voice 01

(Next to the videos)

The two buildings feature in the videos of this series – the old Road Ministry building in the former Soviet republic of Georgia from 1975, designed by the architects George Chakhava and Zurab Jalaghania, and the Cuban National Arts School, designed in 1961 by the architects Vittorio Garatti, Ricardo Porro and Roberto Gottardi – are, as architectural designs, two failures because their construction remained incomplete due to the fall of the collective utopia that originated them.

With regard to the first example, construction work began on the building unbeknownst to the Soviet regime, as it was seen by Georgians as a utopian form of liberation from the State. An identical story is at the root of the abandonment of construction work on the Cuban National Arts School, which originally was a symbol of the revolution and later seen as an extravagance. Both buildings were abandoned for decades, left to the forces of nature and destruction processes.

Between the projected dream, as part of a collective utopia, and the possible demolition as an outcome of these two buildings’ history, there emerges the explorer who, armed with materials found in the waste in the buildings’ interiors, builds a device for navigation and simultaneous protection in order to explore the abandoned spaces, allowing himself to be guided by a desire to discover an inaccessible place on which the greater desire for liberty was inscribed. The (recorded) performance complies thus in part with the building’s purpose, that of a space that can exist as a form of liberation of the body, over being a documentary about the history of these places, including imputation of responsibility for their failure.

In this appropriation of the building there is a counterpoint to the image of a dramatic future. The exploration of a place that has its own risks by means of devices constructed spontaneously from found materials, thus denouncing the fragility implicit in the possible movements of the body, reveals a creative power that is hidden in marginal situations.

Even Garatti, who at first affirms what is inescapable, believes in the power of architecture and in the celebration it devotes to mystery and poetry.

Vittorio Garatti (O.S.)

I love space.

I love movement, the interrelation.

I love open systems that feed on exchanges. I hate closed systems that suffocate.

I love travel, adventure, also as a metaphor, travel as research, research as knowledge, the project as knowledge. A spirit that walks with you, that provides just the right dose of unconsciousness to help you keep faith in the project, so that you are not scared away, at the sight of what organic processes may self-generate.

I love dark places, the places of mystery, hollows of darkness and light.

I love Baroque. I find Vedova’s words to be perfect: “Of all architecture, it is that which is closest to our sensibility; this way of building in the light, those dynamic planes speak to me of a movement akin to contemporary space. Each era comes with its own characteristics, and I find ours, for a number of reasons, seems to be characterised by the non-measurable, by the decadence of classic a priori, by perennial mobility: the opposite of pure concept, of institutional morality, of established laws.”

I love Baroque. I love its instability. I love its absolute permissiveness.

Voice 02

(Next to the go-kart)

The performers are like science fiction characters when, armed with a device that has as much of the archaic as it does of futuristic, they explore the rubble of a civilisation after its total collapse. Said collapse also inherently contains that of the modern project that once united architecture and the social project.

Ironically, the Cuban National Arts School, which was born of a dream of Fidel Castro and Che Guevara’s for a former golf course frequented by Havana’s elites, and was to bring under one roof the different artistic practises as the maximum expression of the liberty provided by the revolution to the collective body, later symbolised, following the increasing proximity of Cuba to the Soviet regime, oppression of individual liberty, with its architects being accused of being bourgeois and forced into exile.

This series questions – through the history of each building – the relationship between what the collective body and the individual body is and how architecture constructs (or can construct) the relationship (or encounter) between the two.

{following the exhibition trajectory based on the sequence of modules}

View of the exhibition EXIST/RESIST – Works by Didier Fiúza Faustino: 1995–2022 (maat, Lisbon, 05/10/2022–06/03/2023). Photo: Bruno Lopes, courtesy of EDP Foundation / maat.

5. My First House (1996)

In the interstitial space of a module, on a wall are two black-and-white photographs. Both show a precarious two-storey structure built of wood and covered with a multi-coloured plastic sleeve, forming an unsightly patchwork. The high trees and the vegetation, which flank the structure, protect the magical place of childhood from the wind. Close to this wall, occupying the central intercalary space, stands the model of the One Square Meter House.

Voice 02

(Next to the photographs)

This is the oldest work in the exhibition, dating from 1996; it already shows some of the characteristic features of the work of Didier Fiúza Faustino, such as those we see in Exploring Dead Buildings and Too Late for Tomorrow, also revealing the fold of time that updates the constant need to question fixed physical structures.

As in Exploring Dead Buildings, this house was built using found materials, harking back to the as found aesthetic defended by the Smithsons. The found objects and materials can be reutilised in a different context and thus be given new meaning.

The very archetype of architecture, the shelter, in this example takes on the function of a game and, with that, of pleasure and laughter.

Voice 01

(Next to the photographs)

The architect is responsible for protecting this unique moment of liberty, allowing the children to build their own house and take control of the space. The context and the materials already exist and are found. But the house was not made with materials. It was made with the children. Not just for them, but with them; it participates in their adventures.

{alternative course around the outside of the exhibition scenography}

{metallic sounds caused by the movement of bodies upwards and onto Democracia Portátil}

View of Democracia Portátil (2016–2022), EXIST/RESIST – Works by Didier Fiúza Faustino: 1995–2022 (maat, Lisbon, 05/10/2022–06/03/2023). Photo: Bruno Lopes, courtesy of EDP Foundation / maat.

6. Democracia Portátil (2016–2022)

A galvanised steel structure, that can be lived in and is mobile, in the form of an amphitheatre and raised by props in the same material, provides for a private moment of meeting between persons. From the space’s interior one can see the whole exhibition design occupying the Oval Room.

Voice 01

(From inside Democracia Portátil)

Based on the curatorial definition of twelve bodies, this archipelago is made up of several islands/bodies, in which there exist fragments of a walled perimeter that collapse to reveal an alternative, more intimate, narrative of said bodies.

They are united by this axis, which is bordered by two works that represent the existing and, at times, antagonistic, duality of the public space between the collective and the individual body. Representing the latter, the work AssWall (2003), produced for the Serralves Museum, transforms the body, that which sits in it, into the museum’s prime exhibit, thus parodying the meaning of a throne as an individual expression that represents a collective, where, in this case, the individual remains in total solitude, swallowed up by the wall.

In opposition to Asswall, Democracia Portátil (Portable Democracy) offers the possibility of creating a public space for meeting and sharing that is protected for communities that are private, but of the real public space. Originally thought of for Mexico City, it was to travel on a pick-up truck to the United States border and then on to New York, gathering words from those to whom a presence and voice in the public space is denied. In this sense, it is also a place of shelter where liberty is protected.

Voice 02

(From inside Democracia Portátil)

This is a heterotopia in the Foucauldian sense: a space that no longer exist and represents the Other to reinstate a condition that was lost somewhere in time. In Mexico it would seek to reinstate democracy in the public space where it no longer exists.

This piece is the maximum representation of a collective public space while recovering the etymology of the word politics, which is rooted in polis, the ancient Greek for city. It is not, however, the Greek polis designed for a single ethnic group, but rather the Roman civitas, the city where citizens of all cultures, ethnic groups and religions came together. Like in this space, from where one can contemplate the most varied expressive forms of individual bodies. It is from shared democracy that one should look at the Other.

As Spinoza writes in his Political Treatise – and an idea that the Allegory of Good Government fresco by Ambrogio Lorenzetti (c. 1337–1340), for example, represents well: “[…] The entire body subject to a dominion is called a Commonwealth, and the general business of the dominion, subject to the direction of him that holds it, has the name of Affairs of State. Next we call men Citizens, as far as they enjoy by the civil law all the advantages of the commonwealth.” (→ 5)

The city is, without exception, the space where all people should have equal access to all commodities and essential goods, which is the basis of any democracy.

{Metallic sounds caused by the movement of bodies downwards and off Democracia Portátil}

-

(5) Spinoza de, Benedict, Political Treatise. Quotation taken from (last visited on 1/3/2023):

https://www.files.ethz.ch/isn/125506/5038_Spinoza_A_Political_Treatise.pdf

Views of the exhibition EXIST/RESIST – Works by Didier Fiúza Faustino: 1995–2022 (maat, Lisbon, 05/10/2022–06/03/2023). Photo: Bruno Lopes, courtesy of EDP Foundation / maat.

7. Body in Transit (2000)

A large, grey suitcase occupies the central space of the exhibition scenario. On it one reads: “Body in transit. Handle with care” next to a symbol highlighting the suitcase’s content.

Voice 02

(Next to the suitcase)

The city, as a democratic collective project, enters into failure when the bodies, as their last hope, opt for an escape that condemns them to death.

Years before the worsening of the migrant crisis, with the repercussions it has today, Body in Transit presented that condition of extreme vulnerability and fragility; through the shape of the suitcase, one understands that it carries a body that has chosen to die over remaining in a place where it is denied that which the city should provide to and guarantee all citizens. The choice to die is the only form of exercising their liberty conceded to such bodies, given the very little chance of survival inside a suitcase in an aeroplane hold.

There is no possible act of redemption at a Venice Architecture Biennale on the theme of Less Aesthetics More Ethics, for which this work was produced, other than the urgency of questioning the important role that is given to architecture: creating a shelter and seeking to protect the most fragile and vulnerable.

Voice 01

(Next to the suitcase)

There is an exercise that is implicit in the Existenzminimum that breaks with the idea provided by the modern project. The minimum space is, in this work, a coffin that holds a body in a foetal position, recalling the moment of greatest fragility as a foetus in the mother’s uterus. The circle of life and death is complete, transforming the work into a funerial ritual for all those who flee oppression.

This is not about imputing responsibility to architecture; but the latter, as a power and control mechanism, contributes to creating ever more restrictive borders, the incarceration of communities because of their differences, the erection of walls and limitation of free flows of people, while at the same time seeing its original social and political function demolished. That which this work makes visible as the only possible way out of the situation.

{Cut to:}

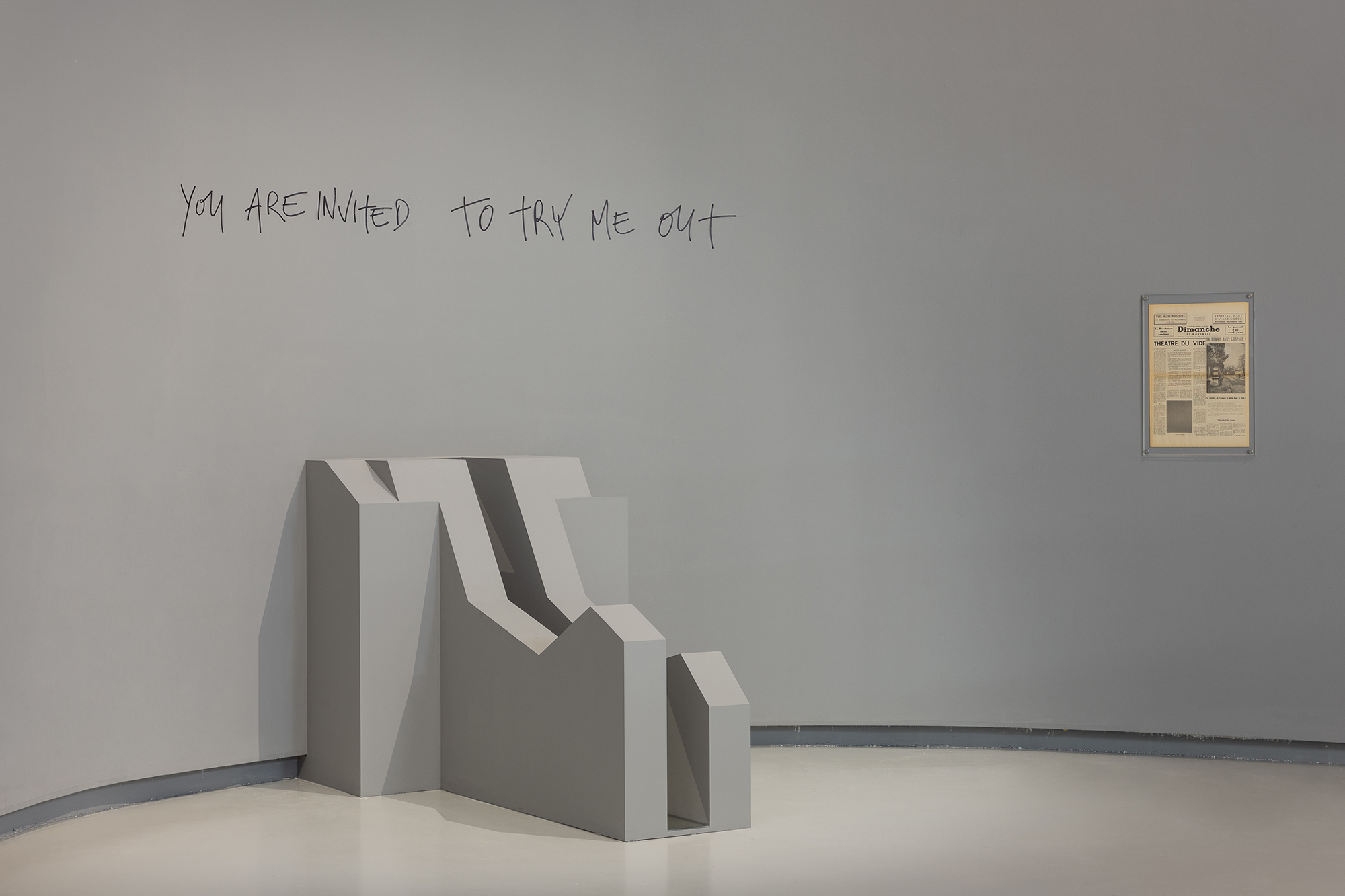

8. Opus Incertum (2008)

On the museum’s curved wall, one reads: “You are invited to try me out” next to a small geometric construction resembling a piece of furniture, but without giving away its function. The image of the body, to which this piece appeals, guides the people to try and find their best position, between an asymmetric inflection of the legs and open arms, look at a mirror that reflects, partially, the suspended body. Beside this, on the wall, is a copy of the French newspaper Dimanche, dated 27 November 1960.

Voice 02

(Next to the newspaper)

Whereas in Body in Transit, the body is enclosed in a situation of tension despite the foetal position, in this work the body carries out what can be considered an extreme exercise of the right of liberty – the body in flight; however, this proves impossible, as in the work by Yves Klein, which served as a reference.

In Le Saut dans le vide, Klein takes a flying jump in a public street. The moment is captured in a black-and-white photograph published in the newspaper with the claim: “Un homme dans l'espace! Le peintre de l'espace se jette dans le vide!”. As he was a figurative and realist painter, as he described himself, in order to paint the space, Klein had to be in the space, in the centre of the void, relieving his body of its own weight, a shield that protects it from the (in)action of the forces of the void.

In Opus Incertum the suspension is simulated and seeks to induce in the body a feeling that it is levitating; this is heightened by the reflection in the mirror, where the coordinates of the physical space are infinitely confused. However, there is a deliberate disconnect between projecting/constructing the ideal body measurements stipulated by ergonomics and the real measurements of the diversity of bodies that try out the structure, in contrast to the liberty that ideal – of suspension – is supposed to give to the body resting in the piece in an uncomfortable position.

The contradiction that emerges in this work reinstates the problem of the relationship between the individual body and the collective body, whereby the latter is commonly thought of as an abstraction of the diversity of individual bodies. Total liberty only seems to exist in an idealised, imagined form.

Voice 01

(Next to the piece that resembles furniture)

Architects, artists and thinkers are continually looking for ways of escaping normativity.

Accordingly, this work denounces the illusion of total freedom, with the Yves Klein piece – hugging the void – being produced in the total safety of the artist’s studio. The jump never took place.

The architectural element uses the body-to-body relationship to create a safe form of a risky situation. How can an architect safely simulate a jump into the void (give freedom to movement of the body)? And create a piece that compensates for the movement of a body falling through space? The result is a negative/normative form of the void, which is, nevertheless, a failure that is assumed before the shapeless void.

Opus Incertum is also the name given to an old Roman building technique used to fill in voids caused by breaks in the built fabric, thus giving new life to the constructions. So, the invitation comes with that meaning: altering the space by means of the body requires experimentation, demands a way out of normativity and also struggle as the ultimate form of liberation.

View of Opus Incertum, 2008, EXIST/RESIST – Works by Didier Fiúza Faustino: 1995–2022 (maat, Lisbon, 05/10/2022–06/03/2023). Photo: Bruno Lopes, courtesy of EDP Foundation / maat

Susana Ventura (Coimbra, 1978) is a Contracted Researcher at the Centre of Studies of Architecture and Urbanism from the Faculty of Architecture of the University of Porto. She holds a PhD in Philosophy from the Faculty of Social and Human Sciences of Nova University Lisbon with the thesis “Architecture’s Body without Organs”. The PhD project included research residences at Diller Scofidio + Renfro, Lacaton & Vassal, and Peter Zumthor studios. She was an Invited Assistant Professor at the School of Architecture, Art and Design of the University of Minho (2018–2022) and at the Department of Architecture of the University of Évora (2019–2021). In 2014, she received the Fernando Távora Prize. Simultaneously with her scientific and pedagogical activities, she develops a research-based curatorial practice. Susana is also a critic of architecture and art.

EXIST/RESIST (maat, 05/10/2022–06/03/2023) is the first institutional exhibition surveying almost thirty years of practice of Didier Fiúza Faustino, the French-Portuguese experimentalist whose work has consistently provoked and transgressed the formal and conceptual demarcations between architecture, design and art. Curated by Pelin Tan, the exhibition brings together for the first time a vast selection of works, preparatory materials, and prototypes – drawings, photos, models, large-scale installations, films, and objects, revolving around four core strands of research that recur in Faustino’s work: “Housing and Dwelling”, “Borders of Bodies”, “Design as Resistance”, “Agonism in Public Space”. Featuring both past and newly created pieces, loans from international collections and never-seen-before documentation from the artist-architect’s private archive, the show is set in a scenography designed by Faustino’s studio – Mésarchitecture, and conceptually devised to put in dialogue two core areas of the museum and thus create two distinctive spatial experiences.