Nuno Cera, Untitled (Flare), 2022

Video, 4K transcribed to HD, sound stereo, colour; 2 min 40 s

Nuno Cera, Untitled (Pier)

Video, 4K transcribed to HD, sound stereo, colour; 2 min 37 s

Texts by Case Miller

Nuno Cera: Untitled (Flare) & Untitled (Pier)

Presented in the context of the exhibition Distant Lights

Shown here, at maat ext. Cinema, from 13 February to 13 March.

From Dusk Till Dawn – Ballardian Bathing 2.0

by Justin Jaeckle

It was on a visit to Álvaro Siza Vieira’s Piscina das Marés project that I wryly tossed off the phrase “Ballardian Bathing” to a friend, to describe the experience of taking the water in a Pritzker Prize winning architect’s celebrated rock pools, in the shadow of a massive functioning oil refinery.

It was on passing the welcome sign to the Parque Natural do Sudoeste Alentejano e Costa Vicentina, just outside Sines – with EDP’s Sines Coal Power Plant behind me to one side, and the beach restaurants and surf schools of Praia de São Torpes on the other – that the phrase came back a second time. A fossil fuel power station as the gateway to a national park has a certain surreality to it. But this notion of “uncanniness”, or the “unheimlich”, is something Nuno Cera – who lived in Sines until the age of twenty-one – must be somewhat “at home” with. His adolescence, after all, was spent in “a place where the beaches and pine forests of old coexist alongside the pipelines that cross the dunes, the rumbles of huge oil tankers, the luminous silhouettes of factories, and the artificially heated waters of São Torpes”, as the current president of Sines municipal council (somewhat Ballardian-ly) put it himself in his text for the Distant Lights exhibition catalogue. Cera’s interest in the built environment, as environment, is not without its own foundations. Nature is naturally a product of human intervention. In Sines, the barrels are more likely to be full of oil than surfed at sea.

This is the terrain of the two videos on this page, Untitled (Flare) and Untitled (Pier), which have their origins as part of Cera’s 2022 exhibition at Centro de Artes de Sines. We could think of that exhibition as a “site-specific retrospective”, gathering, as it did, a specific body of Cera’s work, spanning 30 years, in which the artist engaged with Sines as both place and idea. These older works were accompanied by a set of new commissions reflecting upon the Sines of today (and tomorrow): most notably the two channel video installation Distant Lights, which gave the title to Cera’s exhibition in Sines, and now titles this exhibition’s iteration in Lisbon at maat – Museum of Art, Architecture and Technology. Untitled (Flare) and Untitled (Pier) are two pieces from this new set of works.

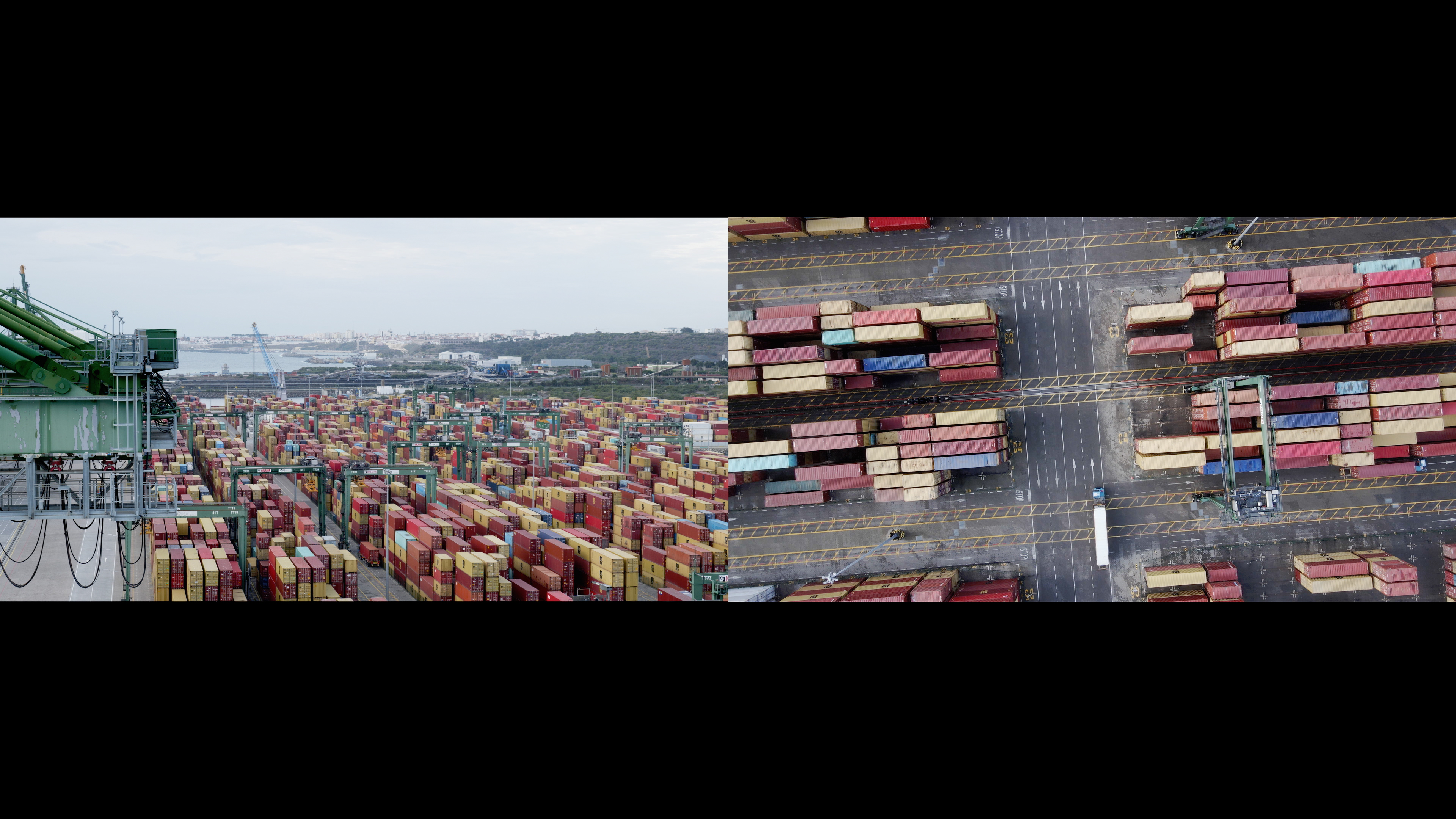

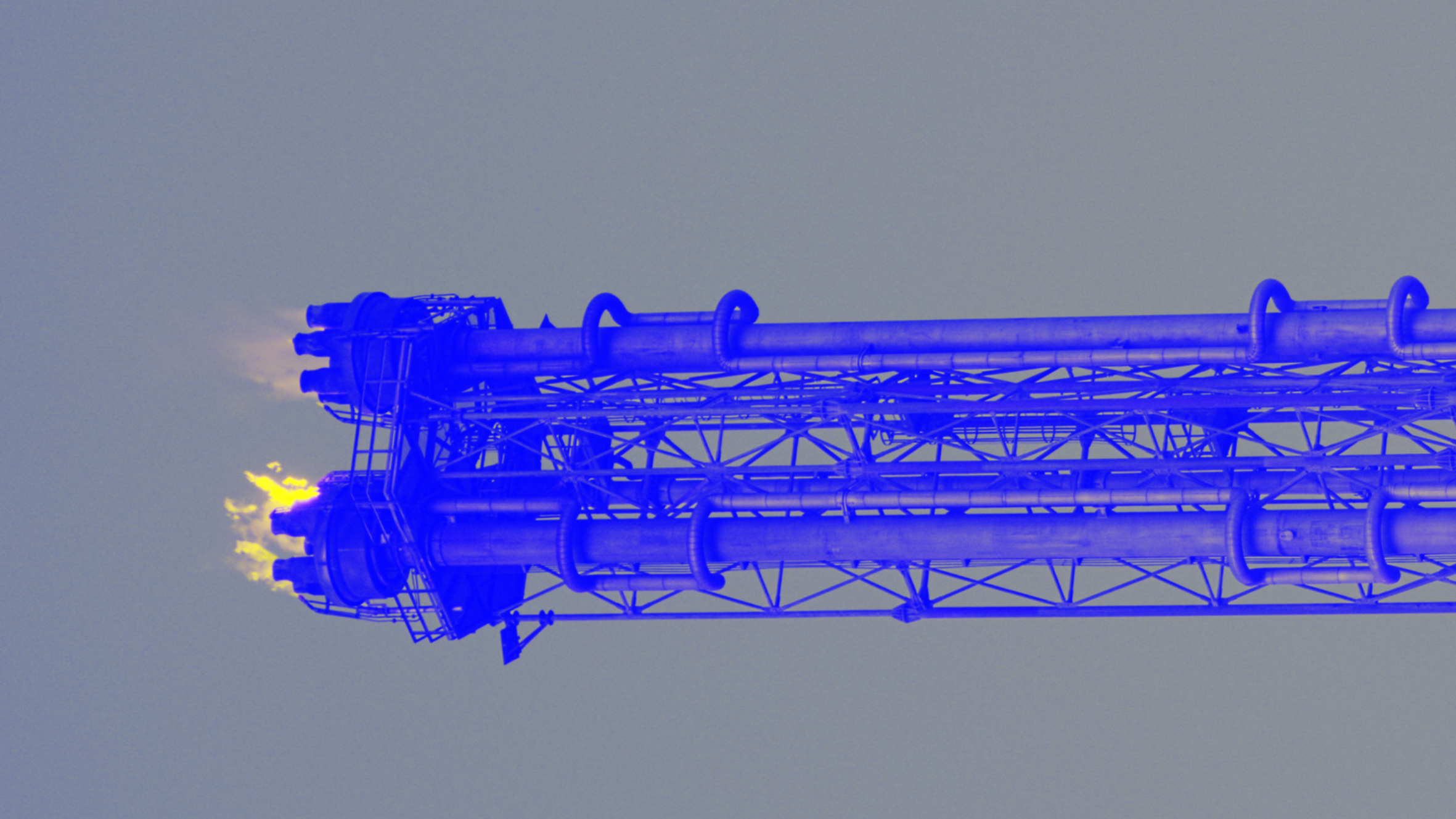

Video stills from Distant Lights, 2022, by Nuno Cera, courtesy of the artist.

|

|

That the reception of an artwork is always affected by the site, conditions and context of its display, that things change their meaning depending on how/where they are seen, is also natural. Often, pains are taken to negate this impact, through a global gallery aesthetic of white cubes that seek to transform “somewhere” into a semi-cosmic “anywhere”. But in a reading of this new body of Cera’s Sines-responsive work, location is both key, and a key. Energy, infrastructure and globalisation, technological innovation and obsolescence, are both the implicit and explicit subjects of this body of work, and the means by which it arrives to a viewer.

First exhibited in the loaded landscape the works respond to and were shot in – Sines – the migration of the exhibition Distant Lights to Lisbon’s Museum of Art, Architecture and Technology – housed in a decommissioned twentieth century power station that once provided energy to the entire city of Lisbon, and financed by Portugal’s largest electricity provider, EDP – sees the show now on display in a room that previously collected the ashes of the power station’s burnt coal. Cera’s somewhat phantasmagoric cartography of Sines’s infrastructural landscape, his ode to industrial and ecological entanglement and his keen images of sites of extraction, now find a home in a “museum” of technology, in a room where carbon once fell to its final cremated rest. There’s an unusually strong simpatico here between these works and their means of delivery to the viewer, that here has the potential to add an additional layer of metaphor, on top of the allegories inscribed within them and the topographies documented by Cera’s lens.

Meanwhile, Untitled (Flare) and Untitled (Pier), now arrive to the viewer via the internet courtesy of maat extended, having also undergone a transformation of their own. Refined, perhaps the way petroleum is transformed into gasoline in the very refinery depicted in Flare, these videos are now around half the length they were when first exhibited in Sines. Originally they were soundtracked by field recordings, now they have acquired a voiceover from texts commissioned from Case Miller for the purpose of the exhibition. The length of these spoken texts determine the length of the two videos, more or less, as Miller’s words accompany Cera’s images, to produce a pair of curt word-image parables, reflecting upon lifecycles, industry, energy and entropy, physical and psychic horizons.

In Pier we see the sea, as it laps against concrete breakers that recall icebergs. This concrete was once sand, before that, rocks and organisms. Eventually it will be sand again. A solitary buoy occupies a place in the rear left of the frame, bobbing its signal of warning, or command of direction. The voiceover speaks of “re-routing” and the impossibility of stopping, as container ships drift across the distant horizon. We’re at the entrance to Sines’s industrial port. The closest European deep-water port to the US. Are we coming, going, or, like that buoy, tethered in limbo?

Flare opens with a Bladerunner-esque nocturnal wide shot of the Sines Galp oil refinery, with two burning chimneys taking the place in the frame that was occupied by the buoy in Pier. We are then presented with the sight of a single flaring chimney, flipped from vertical to horizontal as a kind of artificial horizon. Whether a “torch” or a “beacon”, the flickering of the burning gases – by-products of processing petroleum; petroleum which, in a rhyme between the videos, would have arrived to the refinery through the port in Pier – produce a pulsing halo of light in the digital image, like slow-motion (or crude [oil]) morse code. A solitary figure wanders down a dirt road illuminated by the flame’s flicker (Is it dusk, or dawn? Are we at a beginning, or an end?), before the chimney returns and fills the frame – first upside down, then horizontal again, then estranged as a filter turns it blue; recalling the blue of blueprints. The plans of others?

Video stills from Untitled (Flare), 2022, and Untitled (Pier), 2022, by Nuno Cera, courtesy of the artist.

Watching the flames of dead organisms being reanimated as capital and fuel, and staring out at waves that will keep rolling with or without us, a certain zombie-like quality emerges in Flare and Pier, shared by Cera’s wider body of work for Distant Lights. As the voiceover in Pier puts it, “there is no grave”, after all. A critical interest in human-built infrastructures that have begun to smell of obsolescence makes the works feel like they occupy a space between the living and the dead. There are very few people to be found in these works, just the phantom traces of their civilisation.

While the refinery in Flare is set to expand and the port in Pier is becoming even more valuable in its growing role as a hub for the transport of liquified natural gas (as part of Europe’s efforts to reduce its dependency on Russian energy), Sines’s coal power plant – the gateway to the natural park and the protagonist of the second chapter of Distant Lights – ceased operations in 2021. As did the refinery in Matosinhos by Siza’s pools. And so, as the twentieth century makes way for the twenty-first, my two markers for Ballardian Bathing on Portugal’s coastline are set to be dismantled.

Or rather, transformed. Plans are in place for the site of the shuttered Matosinhos refinery to become an ambitious “new city dedicated to innovation and the energies of the future”. And the same year Sines’s power station ceased operations, installation of EllaLink was completed: a new submarine optical cable linking Portugal and Brazil (and beyond) for the transport of data at a hundred terabytes per second. It’s been said that data is the new oil, but the wealth to be gained from mining it perhaps makes it the new coal too. EllaLink’s own path makes such metaphors physical. After crossing the horizon documented in Pier, the cable lands on the beach in front of the oil refinery from Flare, and continues inland to the embryonic Sines Mega Data Center – Sines 4.0 – which is currently being built on the very site of Sines’s now shuttered coal power station, as part of the region’s ambitious pivot to the new industry of digital tech.

So as the coal ceased to burn, the data centre began to warm in its place, through digital information transformed into light that follows the same maritime route taken by the “Discoveries” 400 years prior. We’re living in a New World on this side of the Atlantic these days too, after all. But, much like the solitary figure in Flare, and the evolving industrial infrastructure of Sines, whether we’re at a new dawn or watching the dusk fall is unclear. While data assumes the place of coal and oil, buried cables topple soaring chimneys, power stations extract cultural value rather than fossil fuelled energy and information flows faster under the sea than the cargo shipped above it into port, what can be perceived in this half-light is an experience of both dawn and dusk, simultaneously.

And as the infrastructure transforms, so Ballardian Bathing evolves. Should you wish to bridge the industrial revolutions of two centuries, and turn “surfing the internet” and “swimming in data” from metaphor to fact, you can now put your beach towel directly on top of EllaLink [right here], and wade out to take the waters above a giant submarine optical cable that carries all the fantasies of the world, as the flares of a refinery continue to burn behind you and giant tankers approach from the horizon. And what could be more Ballardian than that? Let’s call it Ballardian Bathing 2.0. Pier’s waves, meanwhile, will continue to crest and fall, as Flare’s flickering flame oscillates between the uncertainty of signalling a “sanctuary” or a “warning”.

Nuno Cera (Beja, 1972) is a photographer and video artist living and working in Lisbon. His work has been exhibited, published and commissioned by multiple international cultural institutions. He is represented in various public and private collections. Cera was a resident artist at Künstlerhaus Bethanien, Berlin, in 2001 (Calouste Gulbenkian Foundation Grant). In 2003, together with the architect Diogo Seixas Lopes, he published Cimêncio, a work about the suburban landscape. In 2006 he was invited to be artist in residence at the ISCP (International Studio and Curatorial Program), New York City. Between 2007 and 2010, Cera realised the project Futureland, an artistic investigation into the urban growth of nine mega cities. In 2012 he received a grant from the Fundación Marcelino Botín for Symphony of the Unknown I. He undertook artistic residences in Paris in 2013 (International Artist Residency Récollets), and Macau in 2018 (Babel – Cultural Organization and Fundação Oriente). In 2019 he received support from DGartes – Ministry of Culture / Portuguese Republic for Symphony of the Unknown II. Cera was included in the official Portuguese representations at the Venice Architecture Biennial (2004 and 2018).

Justin Jaeckle is a curator, writer and editor, working in the production, dissemination and critique of contemporary culture. With a focus upon cross-disciplinary conversation, he works across criticism, exhibition-making, projects, programming and publications. He is a programmer at Doclisboa International Film Festival (since 2016), and since 2008 has curated the series Architecture on Film, on behalf of the Architecture Foundation, in partnership with the Barbican Centre, London. He has previously curated programme for and in partnership with Tate Modern, Tate Britain, Design Museum, Royal College of Art, Victoria & Albert Museum, Barbican Art Gallery, Auto Italia, Ampersand, Cinemateca Portuguesa and Galeria Municipal do Porto. His writing has appeared in publications including Art Review, Frieze, Contemporânea, RIBA Journal and Wallpaper*.

With Distant Lights (maat, 09/11-13/03/2023, in collaboration with Centro de Artes de Sines) Nuno Cera offers us an external observation of a gaze that extracts the symbolism, which is invisible to our routine gaze; it reiterates the essence of a body in permanent transformation and the simultaneous disintegration of the old that gives way to the new, giving it no time to grow old. The energy and digital transitions that in recent years have marked the territory of Sines, its infrastructures, and consequently its population, have influenced and inspired Cera’s work and in this exhibition – an artistic research looking towards the future – he shares his observations and reflections.