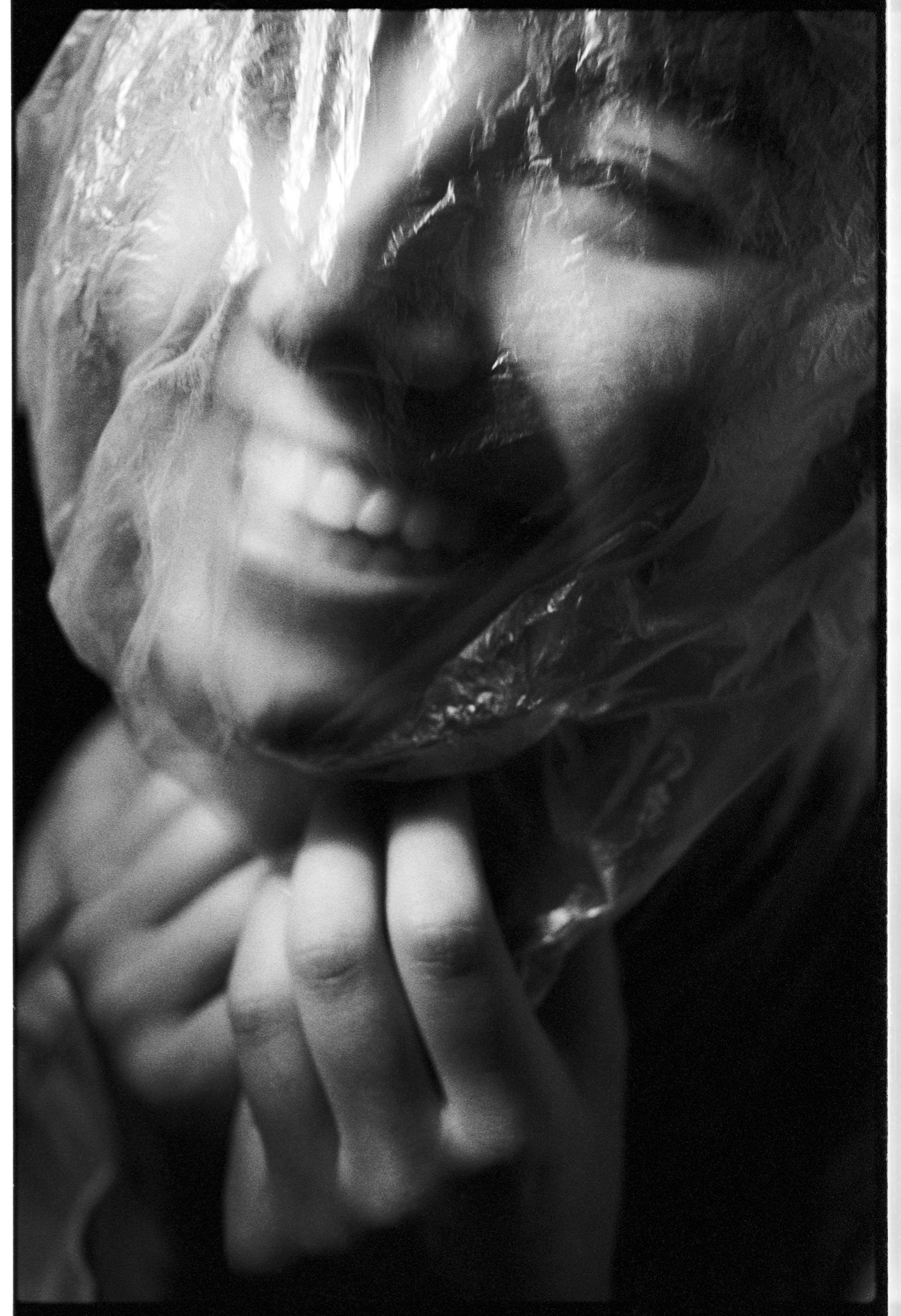

Nuno Cera, Daqui a 30 anos Saudades (Teresa), 1992. Courtesy of the artist.

In 2019 Nuno Cera embarked on a long-term research project about Sines – a city where he spent marking years of his adolescence and took first steps in photography. Distant Lights appeared in 2022, consisting of a photo series and a synchronised two-channel video installation, and gave name to an exhibition and a companion book.

José Mouro

You began your training in photography at the Centro Cultural Emmerico Nunes (→ 1), in Sines. Were you already actively pursuing photography at that time, or did you come to it by chance?

- (1) Established in 1986, the Centro Cultural Emmerico Nunes (CCEN) is a cultural cooperative with a gallery for temporary exhibitions in diverse areas of the visual arts. It is housed in an emblematic building in Sines, the old Misericórdia hospital. The CCEN’s cultural policy is characterised by being open to different forms of artistic expression, both local and national, that promote the debate of ideas, encounters with choices and diverse aesthetics, and the furthering of knowledge and learning.

Nuno Cera

I think it was by chance. I had some interest in photography, and even more in film, but not to the extent of knowing that I wanted to be a photographer. That initial training at CCEN was very important for me to learn the basic techniques, to experiment, and to trigger my curiosity and motivation to see more and to want to learn to see. I remember CCEN being a very stimulating meeting point back then, with the presence of people like you, Al Berto, Helder Lage, Rui Martins and Paulo Correia. Another circumstance that also had some influence was that there were always a lot of family photos in my parents’ house. My father worked abroad for several years, first in Germany, then in Iran, Libya and Algeria, and photography took on a role of communicating and sharing moments of our lives. Perhaps those images sparked something, a desire to record different moments in my life. I think that for many years I used photography as a kind of fight against forgetting. I thought that if something was photographed, it wasn’t lost.

José Mouro

You spent your adolescence in Sines. When you return there, sporadically, is it more for emotional or artistic reasons? Does one of these aspects override the other?

Nuno Cera

I lived in Sines until the age of 21, then Lisbon, and then Berlin from 2000 to 2009. When I returned to Portugal, my trips to Sines were more emotional than artistic: going to restaurants or the beach in São Torpes or the Costa do Norte. On those trips I did have a certain desire to return to this territory and its industry, in an artistic way. I’m attracted to brutal spaces, zones of production and transformation, the form in which the landscape of Sines is unique and very specific, made out of this conjugation of geography, history and industry. Later on, there was a moment when I did come back for artistic reasons, for the exhibition A Secreta Vida das Palavras [The Secret Life of Words], in 2010. For that I wandered through the quarries, the rocks of the Costa do Norte, along the beaches. I took double and triple exposures to produce images that could allow for more readings and be more open to the senses, around the memory and geography of Al Berto’s work. And in the last year I have returned to Sines several times, almost as if I’ve been on a residency, to prepare the exhibition Distant Lights, and it has been an opportunity to see and investigate transformations in the landscape and in the town – for example, the extension of Terminal XXI and the site of the future Data Centre Sines 4.0. It has given me great pleasure to return in this way, to be able to go back to some of the same places 20 years later, and to be inside the giant machines.

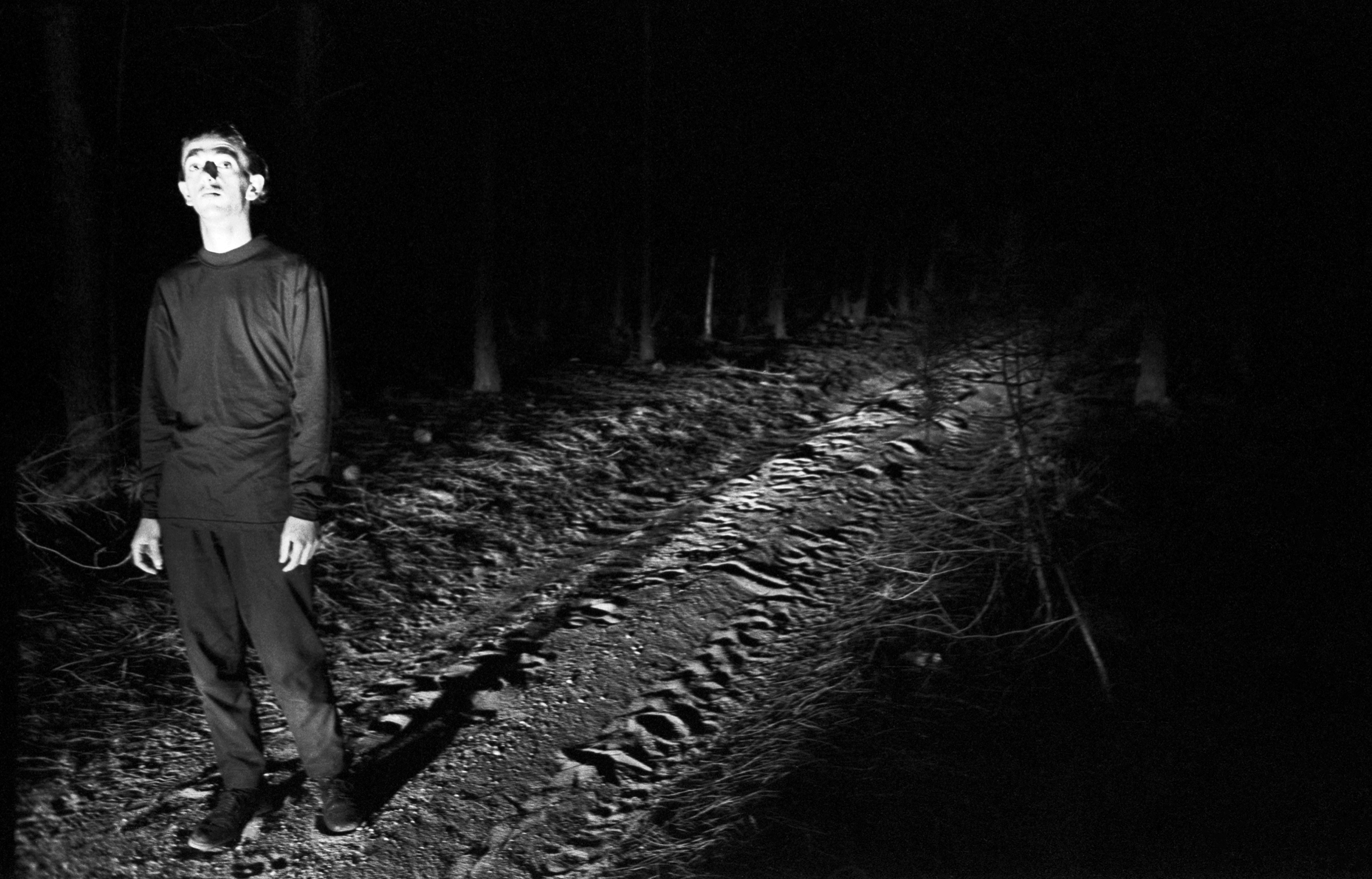

Nuno Cera, Daqui a 30 anos Saudades (José Eduardo), 1992. Courtesy of the artist.

I think that for many years I used photography as a kind of fight against forgetting. I thought that if something was photographed, it wasn’t lost.

Nuno Cera

José Mouro

Daqui a 30 anos: Saudades [30 Years from Now: Longing], (1993). This project essentially focuses on local figures. Is this, as José Soudo wrote, ‘the anticipated longing for realities lived or just dreamed of in their construction...’?

Nuno Cera

The project started from the desire to put together a collection of portraits of friends and at the same time to capture the landscape of Sines. There were two pieces of information – name and place – in other words, each portrait had a specific setting; it was this interaction that interested me. The question of the passing of time was also important; there was an awareness that this moment would disappear (I was 21 at the time). In a very nostalgic way, it’s a longing for a reality lived but also dreamt. Almost a nostalgia of the future. These are portraits in which the gaze is very present, like in the photograph of Alexandre Cascão. José Soudo really understood the project and even identified essential questions for my future work. For me, beyond the issue of aesthetics, photography in general is also a question of memory, document and record. And now, 30 years later, I don’t know whether or not I’m nostalgic about 1993.

José Mouro

In 2000, you returned to Sines with the project Sines 2000, based within the Industrial Complex: “a workstation of lunar ambiences where human presence is almost dispensed with to make way for a self-sufficient device”, as Diogo Seixas Lopes put it. With time having passed, what different perspectives do you feel were revealed in the records of that newer work?

Nuno Cera

The period between 1991 and 2000 was quite intense and one of great personal and academic growth. I left Sines in 1991, I came to Lisbon to study and I think all those changes were reflected in my gaze and my approach to photography. From 1995 to 1997 I was at Maumaus, an independent visual arts school founded by Álvaro Rosendo, Paulo Mora and Adriana Freire, where I learned a more consistent and also technical approach to what photography could be. After a period of making only black and white works, I began to use colour in 1996 and to be influenced by photography from the German school – although black and white, and the early series by Thomas Struth [know more here], from 1978 and 1979, made a great mark on the construction of my language. That was also the moment I discovered the work of Bernd and Hilla Becher and their series on German industry, showing structures and different typologies such as water tanks or industrial towers. A way of both systematising and comparing reality. When I returned to Sines in 2000, my main motivation was to record the different industries in a more objective and documentary way, without human presence. It was a process of preserving a specific moment, at the turn of the century, in that territory, of creating a record for the future and also trying to understand how industry functions. While Daqui a 30 anos: Saudades was based on emotion, friendship and an adolescent impulse, Sines 2000 was an attempt to be more analytical – even the title is very scientific: a place and a date.

Nuno Cera, Sines 2000 (PortSines 1), 2000. Courtesy of the artist.

Nuno Cera, Sines 2000 (APS 2), 2000. Courtesy of the artist.

José Mouro

You spent around ten years in Berlin, the city with the greatest cultural buzz in Europe. You took part in artistic residencies and exhibitions, had contact with artists from all around the world, and gained innovative and radical experiences in the area of the arts. What did you take from that time, in personal and artistic terms?

Nuno Cera

It’s now 22 years since my arrival to Berlin and 13 since my return to Lisbon, and I look back at that time with immense gratitude for the personal and artistic experiences I had, but without nostalgia (I think...). I went there because I received the João Hogan Grant from the Calouste Gulbenkian Foundation, for a year-long residency at the Künstlerhaus Bethanien. It was long, as residencies go, and that gave me time and allowed me to devote myself entirely to the work. It was very important for my career. There was a very strong artistic pulse in the city, where everything seemed possible, from holding exhibitions at home to participating in a project in Prague or having a solo show at a gallery in New York.

Berlin also had a very different atmosphere to Lisbon. This meant that, after the first year, the most natural decision was to stay, as did most of the artists who completed the residency. At that time the city was cheap and offered quality of life and possibilities, as well as a sense of belonging to a community of artists. For several years I shared a studio with artists from Portugal, Denmark and Germany, including Lise Harlev, Morten Schelde, Jorge Queiroz, Noé Sendas, Rui Calçada Bastos and Julien Rosefeldt, on Brunnenstrasse in Berlin-Mitte. That sense of community also made a real mark on my time in Berlin. And there was a group of young curators and critics who had a great curiosity, which created a special energy.

I also feel like I lived in the city at a very good time, when the changes taking place happened slowly and there was a great space and time to think, and, of course, for the no less important parties. It was a period of great activity and personal growth that ended in 2009, by which time I had the feeling that the transaction between what I could give to the city and what Berlin could offer me had been exhausted.

Nuno Cera, Untitled (Al Berto), 2010. Courtesy of the artist.

José Mouro

Untitled (Al Berto), 2010, is an artistic meeting between two old friends. Both of you experienced and recorded this territory, through writing and the image. What have you retained from that experience?

Nuno Cera

The group of four photographs I made for the exhibition A Secreta Vida das Palavras [The Secret Life of Words] was an attempt to capture the spirit of a time and a place in a poetic and experimental way. It involved rereading the poetry of Al Berto, in particular Trabalhos do Olhar [Works of the Gaze] (1982) and Mar-de-leva [Swelling Sea] (1976), and, as I mentioned earlier, I used double and triple exposures to construct images with various readings, that communicated on various levels, and that had a certain sense of melancholy, of loss. The experience of returning to CCEN was very positive, and emotional too, largely because the work on show evoked the memory and presence of Al Berto in Sines. It also made me think about the moments of sharing and growth that happened in CCEN. Twenty-three artists took part in the exhibition and, to quote João Pinharanda, it was a “way of searching, through the Images they construct or find and give to us, for the secret that lies in the heart of Words.” Sadly, CCEN is closed at the moment, but I think the archives of words, photographic records and publications that exist still preserve the memory of that time.

How do our habits and economic relationships alter places, cities and even entire regions?

Nuno Cera

José Mouro

In the exhibition Distant Lights, which is presented this year [2022] at the Centro de Artes de Sines and maat – Museum of Art, Architecture and Technology, you return with these three groups of work from the past, and one from the present, and, again, to the Industrial Complex. What underlies the concept of this project?

Nuno Cera

When you invited me, in 2019, I thought it would be most interesting to again show the work I made in and about Sines in different periods. Distant Lights is an exhibition constructed around an older group of works, with photos from three series: Daqui a 30 anos: Saudades, Sines 2000 and Untitled (Al Berto), alongside a large body of recent work. I approached the challenge as though the exhibition was a mini-retrospective, dedicated to Sines. I think the relationship between these four periods of time will enrich the reading. Our lifestyles, our everyday lives, have produced places, and they need locations like Sines. How do our habits and economic relationships alter places, cities and even entire regions? In a way, I wanted to get a close-up view of those places, those productive chains, the infrastructure, and offer a different perspective on how things happen and how they are. It is a viewpoint built on curiosity, on finding out how the machines and processes of transformation work, about the various relationships between human and machine in the Anthropocene. In the case of the EDP Coal Power Plant, my motivation was to see what remains after such a huge machine is decommissioned, and also (as ever) to capture a very specific moment of transition between two states. It has already been disconnected, but everything is still in its place.

The exhibition also has a certain mission to make public a reality that has always been at a distance from and unknown to most people; to make a little more visible that which happens in this land of “distant lights”.

In the project’s description I wrote that the main objective is for it to be an artistic investigation into the territory of Sines and the initial moments of its transition from energy to digital. It aims to portray that world-body through an artistic look at the Port of Sines and its movements; the energy and maritime transport industries, the machines and their flows; the decommissioning of the EDP Coal Power Plant; the Monte Chãos quarry and the cromlechs. The site/land of the future Data Centre and the transatlantic fibre-optic cable are also important elements. When I started to film and photograph, I understood that the path to explore was the industry/nature dichotomy and the relationships between the artificial and the natural world – because I also very much feel the strength of the natural element in Sines.

The new work is a double projection of synchronised video, Distant Lights, in which parallel screens establish relationships between the seven locations visited (Sines Port Authority, EDP Power Plant, Terminal XXI, Galp, Quarry, Repsol, Data Centre and EllaLink) and the region’s nature. I started from a very simple concept, to place nature and industry in contrast through video. There are two parallel flows that, at certain points, become one, in a visual play of rhythms and sounds that create and deconstruct space and time. It is a documentary-like perspective, that shows more and judges less. During the editing, I chose to divide the video into seven episodes. I am very interested in these open relationships, simultaneous and apparently random, between two images/ two places and what they can convey. Often the important thing is what it is that lies between those two images: what lies between some grazing sheep and some pipes spewing out steam. Early on, I also thought it would be very interesting and beneficial to the project to invite two critics, Case Miller, who lives in Los Angeles, and Joana Rafael, who lives in Porto, to write texts specifically for the project and in reaction to the work. Two external gazes that could add new readings and, to an extent, new fictions. The texts introduce some references to large-scale natural events, climate change, and to a time scale that is more geological. I have worked in close collaboration with critics and authors lately in order to open my visual work to other fields. I sometimes use fragments of texts as voiceover for my videos to create a work that is both more poetic and free.

I also made another two videos, which are more contemplative. One is a view of the east pier (which was destroyed, I think, in the storm of 1986); a ruin that holds a symbolic charge for Sines and which I had previously photographed in 2000. There is a powerful moment there between the artificial and the natural. The other video is made solely out of different shots of the refinery’s gas flare at dawn.

I also present four large photographs, sized 180 x 125cm; three medium, at 125 x 70cm; and 30 small prints. I photographed different locations, and they function together like a small tour. It’s a constellation that seeks to capture the spirit of the place. To finish, in the large hall, I have a large print on fabric showing a photomontage, in a reference to the painting The Castle of the Pyrenees by René Magritte [more information here], from 1959 – a huge flying stone.

In other words, various episodes and poetic and artistic glimpses of different times, spaces and movements coexist simultaneously. The aim is to create a visual memory of this moment in the history of Sines, and to produce an artistic experience that invites the public to reflect on contemporary questions that affect our society.

1.

|

|

2. |

|

3. |

|

|

4. |

5.

5.

Nuno Cera, Distant Lights, 2021. Courtesy of the artist.

1. APS

2. A2

3. Pedreira 1

4. Central EDP 1

5. Costa do Norte

José Mouro

After two years, we appear to be reaching the end of the Covid-19 pandemic, which caused profound transformations in us and in the world we then knew. How was that period for you, personally and artistically?

Nuno Cera

The early days of the pandemic were quite strange for me. I had some panic attacks and I felt the fear of uncertainty. After that first period, I approached the lockdowns, as many people did, as an opportunity to reorganise and to use that slower pace as a time to reflect and, for example, re-do my website.

The pandemic began with the cancelling of various exhibitions, in particular my involvement in a major exhibition on the work of Álvaro Siza in Macau, through a new work made in China. Fortunately, at the same time, I was preparing a new video installation of three synchronised channels, with the title Symphony of the Unknown II, which was supported by the Ministry of Culture and the School of Arts of the Catholic University, and aimed to identify the unknown spatial qualities of three architectural complexes: the university campus of the Collegio del Colle (by Giancarlo De Carlo, from the 1960s, in Urbino, Italy), the National Archive-Torre do Tombo (by Arsénio Cordeiro, from the 1980s, in Lisbon), and the City of Culture of Galicia (by Peter Eisenman, from the early 21st century, in Santiago de Compostela, Spain). The project was conceived of as a ‘visual symphony’, creating a territory in which three episodes and poetic glimpses of different times coexist in evanescence. After having managed to finish filming after the first lockdown, I had plenty of free time to edit the video and to devote myself to the publication, which was important for the final result. I also made another video, Hello Tomorrow, taken from my home in Largo da Madalena, in the historic centre of Lisbon, in which I used that view of the street as an observatory for the transformations in the city – from the presence of mass tourism to the absence of bodies as a result of the pandemic. It is another of my works about the passing of time. I also took some photographs of the Baixa area of Lisbon, without life or tourists, during a time which now already seems long ago. I was also interested in that perception of the passing of time during the pandemic; a relative time, where the days in lockdown were all very similar and seemed to be consumed both slowly and quickly, simultaneously.

Nuno Cera, Distant Lights (Central EDP 2), 2021. Courtesy of the artist.

Art has a different sensibility and rhythm – and a responsibility to help caution, to stimulate conversations and dialogues, to capture points of view and opinions for generations to come.

Nuno Cera

José Mouro

This conversation is taking place during the third week of the conflict between Russia and Ukraine. What role does art play, or could it play, in this very complex and broad context?

Nuno Cera

It is extremely painful to see images of war again, to imagine the destruction of lives and families, to try to put myself in their place, to ask “What if it was me? What could I do?”, to think about traumas, annihilation and to question the reason for a return to war. Your question is quite hard to answer, but I think art will always play a very important role in understanding the world. In immediate terms, there are initiatives such as artistsatrisk.org [know more here], which tries to support artists around the world, particularly Ukrainians right now, through a network of contacts and opportunities. Artists tend to show solidarity towards each other, and generally try to help by means of donations or through a more direct involvement. There is also a network of artists operating in central Europe. Friends from Berlin have told me about people who went to the border to bring back refugees in their cars. The initiatives of civil society tend to do more than the official ones. Art can also offer a form of reflection on the moment and the traumatising experiences of war. Art has a different sensibility and rhythm – and a responsibility to help caution, to stimulate conversations and dialogues, to capture points of view and opinions for generations to come. It also has the power to be a political tool, as we saw in the refusal of artists of the Russian pavilion to take part in this year’s Venice Biennale. I don’t really have a very clear opinion on the cancelling of shows and exhibitions featuring Russian artists in the West.

José Mouro

In light of this war, and its global consequences, Sines is called on to play a new role in the process of re-industrialisation. And I’m sure that, as a photographer, you will come back to this place. Are you curious, or do you have any expectations, about the transformations that might take place here?

Nuno Cera

I’m always very interested in understanding the reasons behind changes to a certain territory, to an industry and a landscape, because things never remain the same forever. We might think, for example, that in a hundred years’ time there will be no more petrol pumps, even if right now that seems unreal. I’ve been following the news about new investments and the way Sines could be a very important place for Portugal in terms of logistics, energy and technology, and I’m obviously very curious to see those changes and the possible transition to a low- carbon economy. I also feel there’s a huge range of factors, economic, global, related to supply-chain flows, that are all connected. The world really is a complex place. Will we have an auspicious future, or are we heading towards an environmental dystopia?

Nuno Cera (Beja, 1972) is a photographer and video artist living and working in Lisbon. His work has been exhibited, published and commissioned by multiple international cultural institutions. He is represented in various public and private collections. Cera was a resident artist at Künstlerhaus Bethanien, Berlin, in 2001 (Calouste Gulbenkian Foundation Grant). In 2003, together with the architect Diogo Seixas Lopes, he published Cimêncio, a work about the suburban landscape. In 2006 he was invited to be artist in residence at the ISCP (International Studio and Curatorial Program), New York City. Between 2007 and 2010, Cera realised the project Futureland, an artistic investigation into the urban growth of nine mega cities. In 2012 he received a grant from the Fundación Marcelino Botín for Symphony of the Unknown I. He undertook artistic residences in Paris in 2013 (International Artist Residency Récollets), and Macau in 2018 (Babel – Cultural Organization and Fundação Oriente). In 2019 he received support from DGartes – Ministry of Culture / Portuguese Republic for Symphony of the Unknown II. Cera was included in the official Portuguese representations at the Venice Architecture Biennial (2004 and 2018).

José Mouro taught Portuguese in several Primary and Secondary Educationv schools, both public and private. In Angola he taught Portuguese Language and Culture and later worked at the Secretary of State for Culture where he elaborated the programme for the future Artistic Training School (under the cooperation agreements between the Portuguese and Angolan State). In 1987, together with the poet Al Berto, among others, he was founding partner of the Centro Cultural Emmerico Nunes, in Sines. There, he assumed various responsibilities like direction, management, programming and curatoing. More recently he was coordinator, programmer and curator at the Centro de Artes de Sines. He has worked in curatorial projects with several national and international artists.

With Distant Lights (maat, 09/11-13/03/2023, in collaboration with Centro de Artes de Sines) Nuno Cera offers us an external observation of a gaze that extracts the symbolism, which is invisible to our routine gaze; it reiterates the essence of a body in permanent transformation and the simultaneous disintegration of the old that gives way to the new, giving it no time to grow old. The energy and digital transitions that in recent years have marked the territory of Sines, its infrastructures, and consequently its population, have influenced and inspired Cera’s work and in this exhibition – an artistic research looking towards the future – he shares his observations and reflections.