Pamir: Roof of the World

by Vladimir Yerofeyev (1927), special edit and score by Carlos Casas (2018)

Shown here from 15 September to 15 November 2020.

“Film-maker Vladimir Yerofeyev (1898–1940) was a pioneer of expedition cinema in the Soviet Union, advocating for increased attention and investment in edifying non-fiction films made to win the interest of broad audiences. Pamir. Roof of the World, 1927, is his second feature film, and the first resulting from an expedition … In summer 1927, a trek to the mountainous Pamir region, known as the 'Roof of the World', in present-day Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan, was organized by the Sovkino studio in co-operation with the Geological Committee. … The film opens with an animated map presenting the itinerary. Starting off in Moscow, the symbolic center of the new empire, it leads through Samara and Orenburg to Tashkent, Osh, and further on to the Pamir Mountains of Central Asia. …”

Oksana Sarkisova, 2017

"Pamir. Roof of the World", 1927

35 mm film, black and white, silent; 71 min

Directed by Vladimir Yerofeyev (Vladimir Erofeev)

Cinematography by Vladimir Shneyderov

Photography by Vasilii Beliayev

Produced by Sovkino, USSR

Promethean Utopianism: The Writings of Nikolai Fedorov

selected by Carlos Casas

The destiny of the Earth convinces us that human activity cannot be bound by the limits of the planet. We must ask whether our knowledge of its likely fate, its inevitable extinction, obliges us to do something or not. Can knowledge be useful, or is it a useless frill?

In the first case, we can say that Earth itself has become conscious of its fate due to man, and this consciousness is evidently active – in pursuit of the path of salvation. The mechanic has appeared just as the mechanism has started to deteriorate. It is absurd to say that nature created both the mechanism and the mechanic; one must admit that God is educating man through his own human experience. God is the king who does everything for man but also through man. There is no purposefulness in nature – it is for man to introduce it, and this is his supreme raison d’être. The Creator restores the world through us and brings back to life all that has perished. That is why nature has been left to its blindness and mankind to its lusts.

Through the labour of resuscitation, man as an independent, self-created and free creature freely responds to the call of divine love. Therefore humanity must not be an idle passenger but the crew of its terrestrial craft propelled by forces the nature of which we do not even know – is it photo-, thermo- or electro-powered? We will remain unable to discover what force propels it until we are able to control it. In the second case, that is to say, if the knowledge of the final destiny of our Earth is unnatural, alien and useless to it, then there is nothing else to do than to become passively fossilized in contemplating the slow destruction of our home and graveyard.

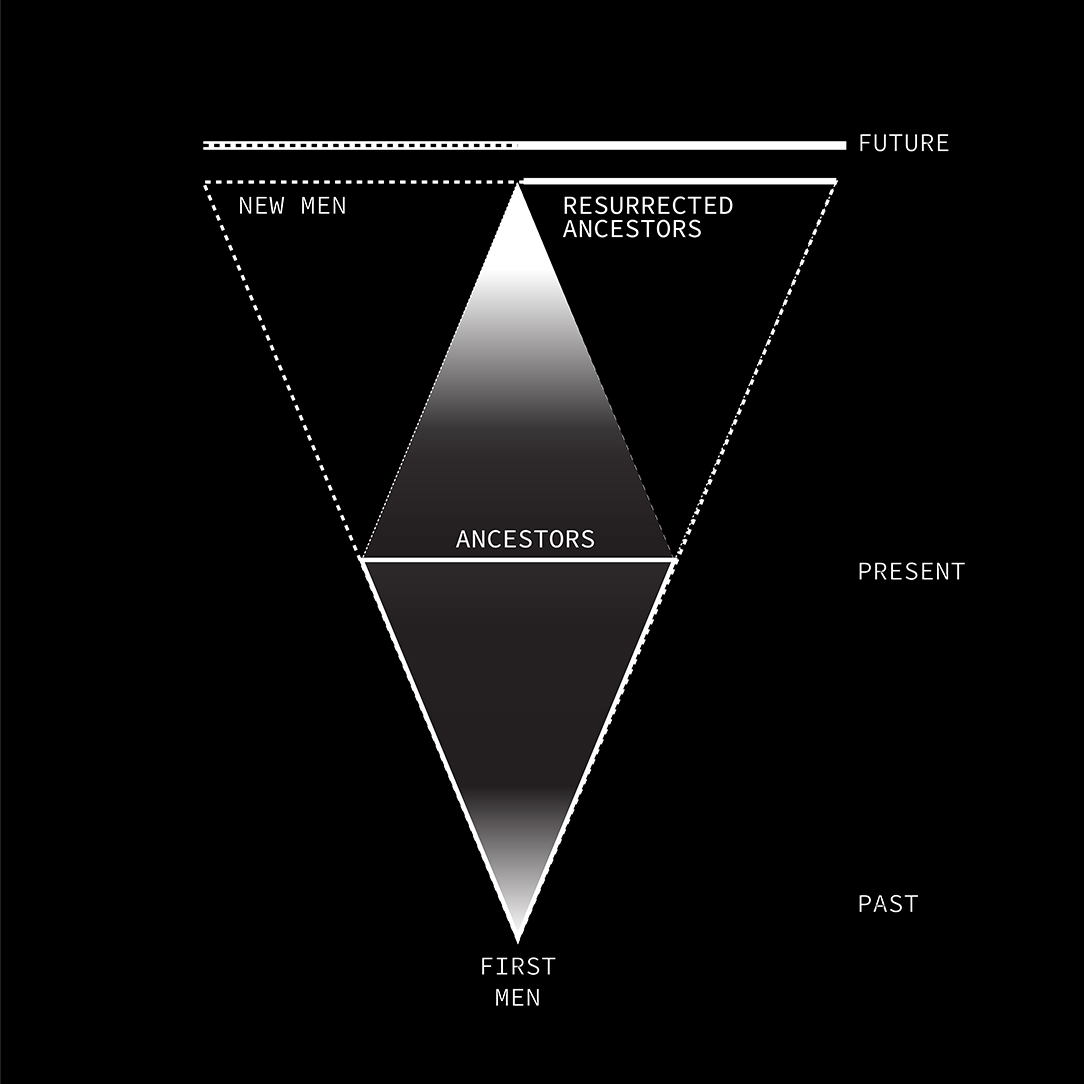

“One should live not for oneself nor for others but with all and for all.” Nikolai Fedorovich Fedorov (1829–1903) refers here to all people throughout time (past, present and future). He is speaking of a project to unite humankind, the colonisation (“spiritualisation”) of the universe, the quest for the Kingdom of God, the creation of cosmos from chaos, the death of death, even the resurrection of the dead. Fedorov believed, and passionately felt, that resignation in the face of death and separation of knowledge from action was false Christianity. He cautioned against being fooled into worshipping the blind forces of Satan. Rather, one should actively participate in changing what is into what ought to be. Indeed, it is increasingly felt that humanity is taking over the course of evolution and the fate of the planet Earth from nature. To use the word coined by Pierre Teilhard de Chardin (1881–1955), our era is that of the “noosphere”.

Whatever topic he wrote about, Fedorov introduced his main idea of the Common Task – how to achieve universal brotherhood, rationalise nature instead of merely exploiting her bounties, overcome death, resurrect our ancestors and create a united humanity worthy of governing the universe. His obsessive emphasis on the duty of sons to resurrect their forefathers can possibly be ascribed to his traumatic childhood experience of losing both his father and his grandfather at the age of four, and to a subconscious guilt complex for having failed to keep them alive through adequate love. However, there is also a theoretical reason for his emphasis on filial love, for although humans share with other animals both sexual love and love for their offspring, only human adults remain tied by affection to their parents when they no longer need their protection in order to survive. climate in an earlier geological era), it has been thought that the cradle of the human race might have been located there, so Fedorov advocated sending an Anglo-Russian scientific expedition – uniting two usually hostile nations in a joint venture – to discover the bones of these early men and provide tangible proof of human kinship.

The study of the Earth’s magnetism might lead to an understanding of the force which propels the planet through space and, perhaps, to the utilisation of that force for space travel and emigration to other planets from an eventually overpopulated earth. For Fedorov, it was time we stopped being “idle passengers” on our planet and became “the crew of our celestial craft”. Indeed, the potential of humankind is boundless, provided it stops wasting its energies on discord and dissension, which are both the consequence and the manifestation of immaturity, and unites in a common cause that will lead it to adulthood and participation in the creation of a New Heaven and a New Earth.

“One should live not for oneself nor for others but with all and for all.”

Nikolai Fedorovich Fedorov (1829–1903)

Image courtesy of Carlos Casas. On this same topic of "The Philosophy of the Common Task" and Nikolai Fedorov's writings, Carlos Casas also made this video available.

Carlos Casas

Pyramid of Skulls, 2017

Discrepant (CREP42)

Double LP; 68 min 68 s

Music and sounds recorded and mixed under the spell of Nikolai Fedorov and the Common Task, as well as inspired by the teachings of Jonboz Dushanbiev, and the people of Pamir in Tajikistan. Carlos Casas deconstructs far away sights and sounds to create a unique field recording experiment that worships past, present and future traditions equally.

The present cosmos, which it would be more correct to call chaos, will cease to be a desert strewn with worlds, like sparse oases, most of which are probably inanimate except for one small planet destined perhaps to populate the others. For the resources of any planet, however great, are eventually limited, and consequently an isolated world cannot maintain immortal beings. And why should they not be immortal? Death is inevitable today because of man’s ignorance and consequent helplessness. Death is a form of epidemic disease. Sometimes it is even difficult to diagnose at what moment a human being is actually dead. The only certainty comes with the decomposition of the body. Better knowledge of physiology and psychology should make it possible to prevent the decomposition of corpses and achieve bodily immortality – and immortality cannot be the privilege of one generation alone. So the ultimate goal of the Common Task was to achieve, scientifically and in accordance with God’s design, the resurrection of the dead.

Pamir is the centre of the world’s unrecorded history, since Chinese, Indian and Semitic myths about the origins of their respective nations seem to point to it – this mountainous region of Central Asia often referred to as “the roof of the world”. Fedorov considered the Pamirs a “pyramid of skulls”, a mountain of humanity sedimented layer by layer, forsaking a vision of humanity where all people will be resurrected and all will be able to share the world. This idea of the Common Task is probably one of the most radical theories I have ever grasped and certainly one of the most complex and ever expanding philosophical ideas, more relevant today than it was a century ago.

Carlos Casas is a filmmaker and artist whose practice encompasses film, sound and the visual arts. His films have been awarded in festivals around the world, like the Venice Film Festival, Buenos Aires International Film Festival, Mexico International Film Festival, CPH DOX Copenhagen, FID Marseille and the International Film Festival Rotterdam, and presented in several festivals and cinematheques. His work has been exhibited and performed in international art institutions and galleries, such as Tate Modern, Fondation Cartier, Palais de Tokyo, Centre Pompidou, NTU CCA Singapore, Hangar Bicocca, GAM Torino, Bozar, among others, and also at the Triennale di Milano.

Atypical Traditions, curated by Gonçalo F. Cardoso, is a music programme that aims to reconfigure our idea of history and traditional thinking to shape a brave new vision of the past, present and future. Taking a no-holds-barred attitude to the past and proposing a complete reinterpretation of the future, artists from different backgrounds and geographies (Portugal, Spain, US, UK) present new musical perceptions that try to find new meanings in an everchanging ultra-globalised society. In the context of the first of four themes — entitled “Visions at the End of the World” —, Carlos Casas performed the 19th incarnation of “Avalanche”, a work in progress (started in 2009) about Hichigh, one of the world's highest inhabited villages in the world, in the Pamir mountains, Tajikistan). This site-specific film is adapted and reedited in relation to the context each time it is presented.