Vulnerable Beings: a Lexicon

by Andrea Bagnato and Ivan L. Munuera

A

Activism

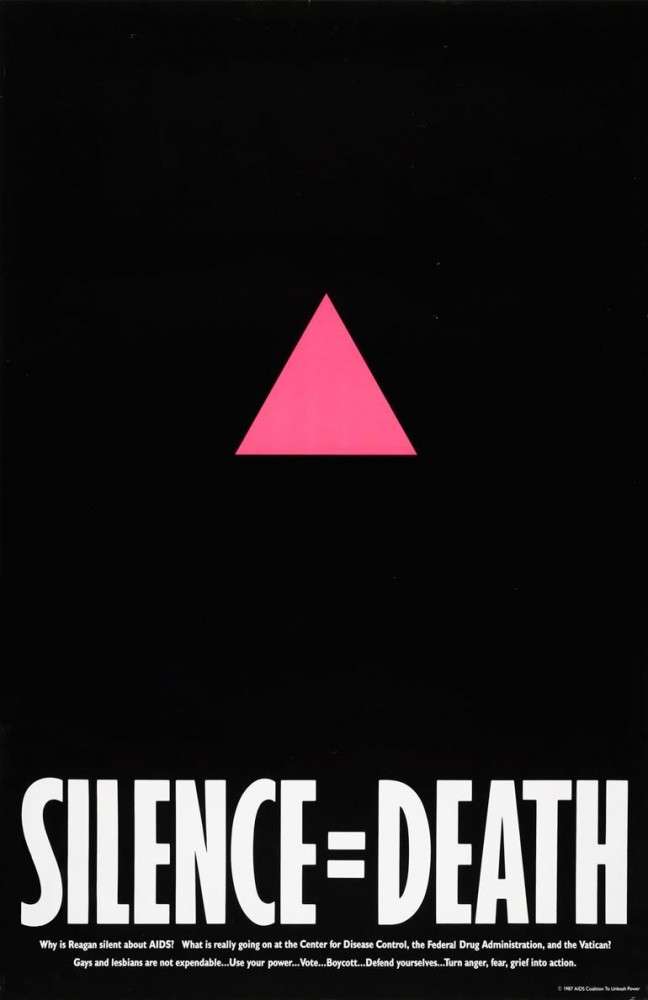

The intersectional and complex activism created by ACT UP in New York to confront the HIV/AIDS crisis has permeated the way political engagement can be understood to this day. Hailing from different backgrounds, ACT UP members simultaneously worked to debunk myths and exclusionary policies, advocated for a horizontal way of discussing politics, opened the black box of medical knowledge, confronted the segregationist practices of media, governments, and institutions, and proposed a new way of understanding engagement and creativity. The work of ACT UP can also be understood within and measured against a global geography of collective mourning.

In 1986, Avram Finkelstein was co-founder of the group Silence=Death Project, which created the “Silence=Death” logo to combat institutional silence surrounding the stigma of HIV/AIDSm which was later donated to ACT UP. Courtesy of ACT UP/Avram Finkelstein.

B

Bodies

"In 2018", Jasbir Puar writes, "Gaza became the theatre of explicit maiming; no longer accidental or incidental but intentional in its scale and intensity, witnessed and sanctioned by global audiences." During the protests known as the Great March of Return, the Israel Defence Forces aimed deliberately at the lower limbs of at least 6,000 Palestinians, as found by an inquiry of the United Nations. In seeking to cripple not just individual bodies but an entire generation, Israel may be seen as testing out a new form of biopolitical control, exploiting liberal understandings of disability to legitimise its actions. When maiming intersects with the structural oppression and debilitation of Palestinian lives, what is the true duration of an act of violence? How is disability lived within the domestic sphere, and how does it affect social reproduction? What does it mean to maintain a population in a condition of "perpetual injury"?

Borders

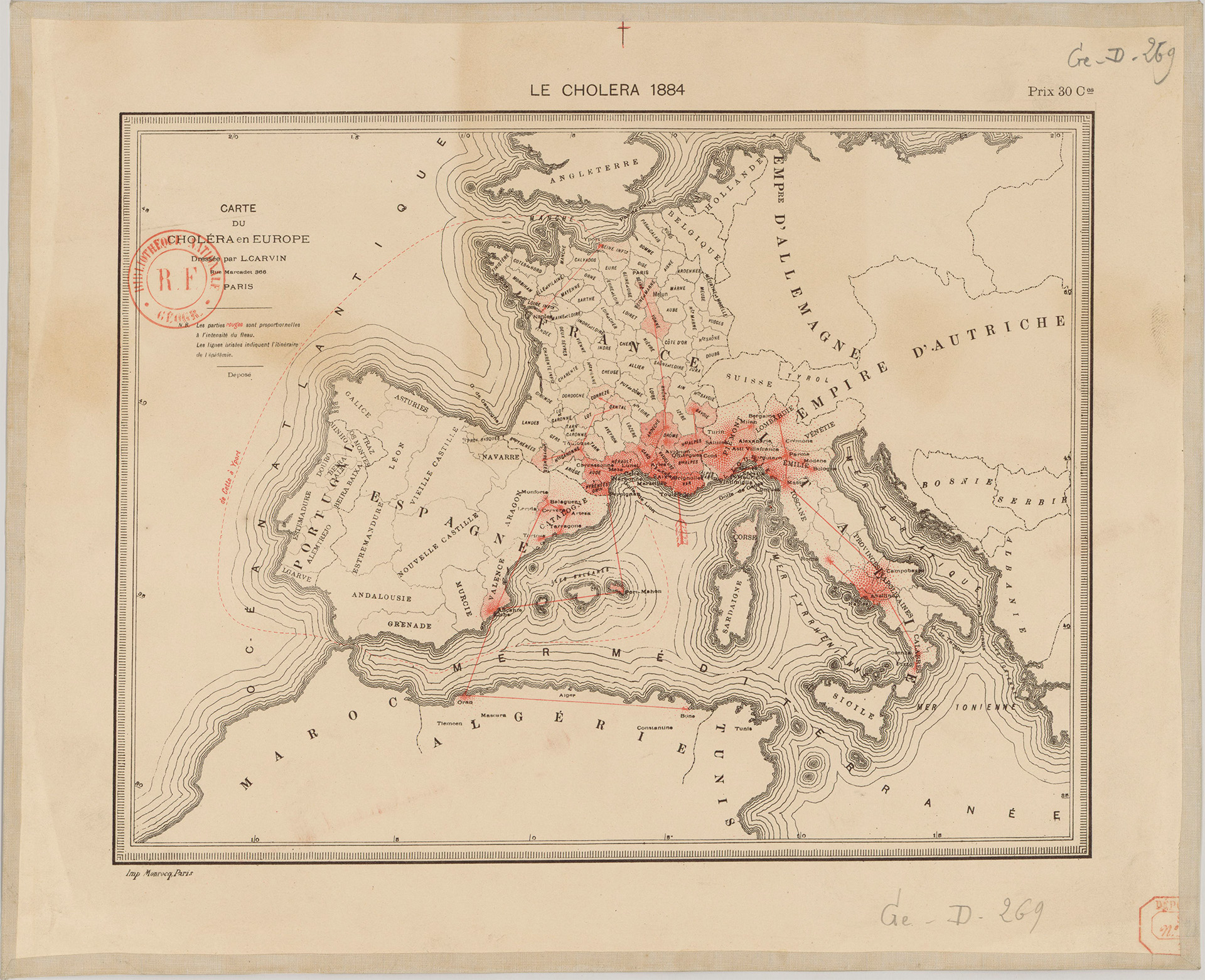

Aedes albopictus, or Asian tiger mosquito, is a peculiar species prone to transmitting multiple severe diseases such as dengue, yellow fever, and Zika. Present in Southeast Asia for a long time, it spread to the United States and Mediterranean Europe in the 1980s, hiding in the cracks of global shipping – from used tires to domestic bamboo plants. Governmental attempts at controlling the tiger mosquito regularly fail, and its habitat is only expected to expand as the climate warms. The Aedes mosquito defies border regimes, and challenges categories of "native" and "invasive". Above all, it requires us to find new ways of thinking vector species and pathogens – beyond modern ideas of taxonomy, territory, and governance.

Louis Carvin, map of the 1884 cholera epidemic in Europe. Source: Bibliothèque nationale de France, GED-269.

C

Cities

The imposition of domestic confinement as a public health strategy has a long historical genealogy – inhabitants of medieval cities were regularly forced to stay at home during plague epidemics. Yet, its contemporary application is without precedent in scale and pervasiveness. They way millions of people live today – in small individual apartments, owing to ever-increasing real estate prices – has been a powerful spatial barrier to any form of proximity and shared experience. Displaced or homeless people, already undergoing systemic and structural exclusion, have been particularly affected. If we are to imagine more communal ways of getting through moments of pain and suffering, values such as "privacy" and "individuality" may have to be challenged – paying more attention to ways of living and architectural arrangements that go beyond the modern Western norm.

In the plague epidemic of 1682, the city of Ferrara suspended all trade with the German state of Thuringia as an attempt to stop contagion. Source: Wellcome Collection EPH501.

Coloniality

On Réunion Island, a colony since the 1600s, histories of the thousands of abortions forced on women of colour intersect with colonial deforestation and the recent chikungunya epidemic – which the French government blamed on the local population and did nothing to tackle. When epidemics are understood not as an isolated, "natural" phenomenon but as a consequence of the historical layers of North-South coloniality, medical histories take on a far less settled meaning. Further, they turn both the individual and collective body into a powerful site of resistance.

Colours

Yellow fever was introduced in the Americas in the 17th century. It was inadvertently carried on the ships used by European traders to transport enslaved Africans. A disease of colonial origins was then made worse by the ecology of the sugar plantations in the Caribbean and Northeast Brazil – as cutting down forests created a favourable habitat for the Aedes mosquitoes that transmit the virus. After having seemingly been brought under control with public health campaigns, yellow fever reappeared in Brazil in 2018 – possibly a consequence of contemporary deforestation in the Amazon. 2018 was also the year that Jair Bolsonaro’s government took power, and epidemiological concerns were woven into the nationalist politics of their campaign.

D

Dwelling

"Disease", according to Francesco Urbano Ragazzi, is “the hidden agent that reinstates disorder, the archaic strength that shows the vulnerability of the world, but also and above all its amazing resistance." San Francisco was notoriously one of the earliest cities to be affected by the HIV/AIDS epidemic, where the first cases of Kaposi's sarcoma were diagnosed in 1980. In the following years, the city saw a veritable wave of evictions, as landlords used the epidemic to gentrify neighbourhoods that had long been home to the queer community. In a neoliberal world, even deadly viruses can be co-opted to accelerate the financialization of the home and the normalisation of LGBTQ+ culture. The combination of precariousness, rising rents, and regular moves was firstly, and most heavily, experienced by marginalised social groups – but is now becoming a common condition even among the once-affluent middle classes. And yet even in such context, new forms of living and inhabiting emerge and are continuously tested and rearranged.

Tomaso De Luca, “A Week’s Notice”, 2020. Video still. Courtesy of the artist and Monitor gallery.

E

Empire

In the years after 9/11, terrorism was increasingly described in the West as an "epidemic" – a language peculiarly targeting Muslim populations and Muslim-majority countries. Acts of mass violence were conflated with contagion and illness; they were explained by resorting to the same imaginary of random, unknowable threats to the social body. Such metaphors are not a contemporary phenomenon but can be traced back to the early days of epidemiology in the 1850s and its roots as a tool of imperial management – when the colonised masses were regarded as a public health threat, and acts of resistance were portrayed as terrorism. The way epidemiological language has been deployed to feed racial constructs – and Islamophobia in particular – calls into question the very foundations of modern medical knowledge.

K

Kinship

Since the beginning of the 1980s, when HIV/AIDS jumped into public attention through media coverage, different communities created a new definition of kinship through their activism. This form of kinship was not based on the traditional understanding of lineage (consanguinity, phylogenetic relationships, nuclear family structures), but on the shared engagement with a virus (HIV) and a disease (AIDS). HIV was the biological agent that allowed kinship to form among its carriers, acting as both kin and the apparatus by which kin was created. But these ties were not only biological – they were also social and political. Not all the people involved carried the virus or shared the same positive status, and even if they shared it, there were multiple thresholds determined by the viral load: undetectables, HIV positive with no AIDS, false positives, etc. Thus, the bonding between community members was more than biological. What they shared was a “chosen kinship”: an understanding of their relationship with HIV and AIDS in an activist way.

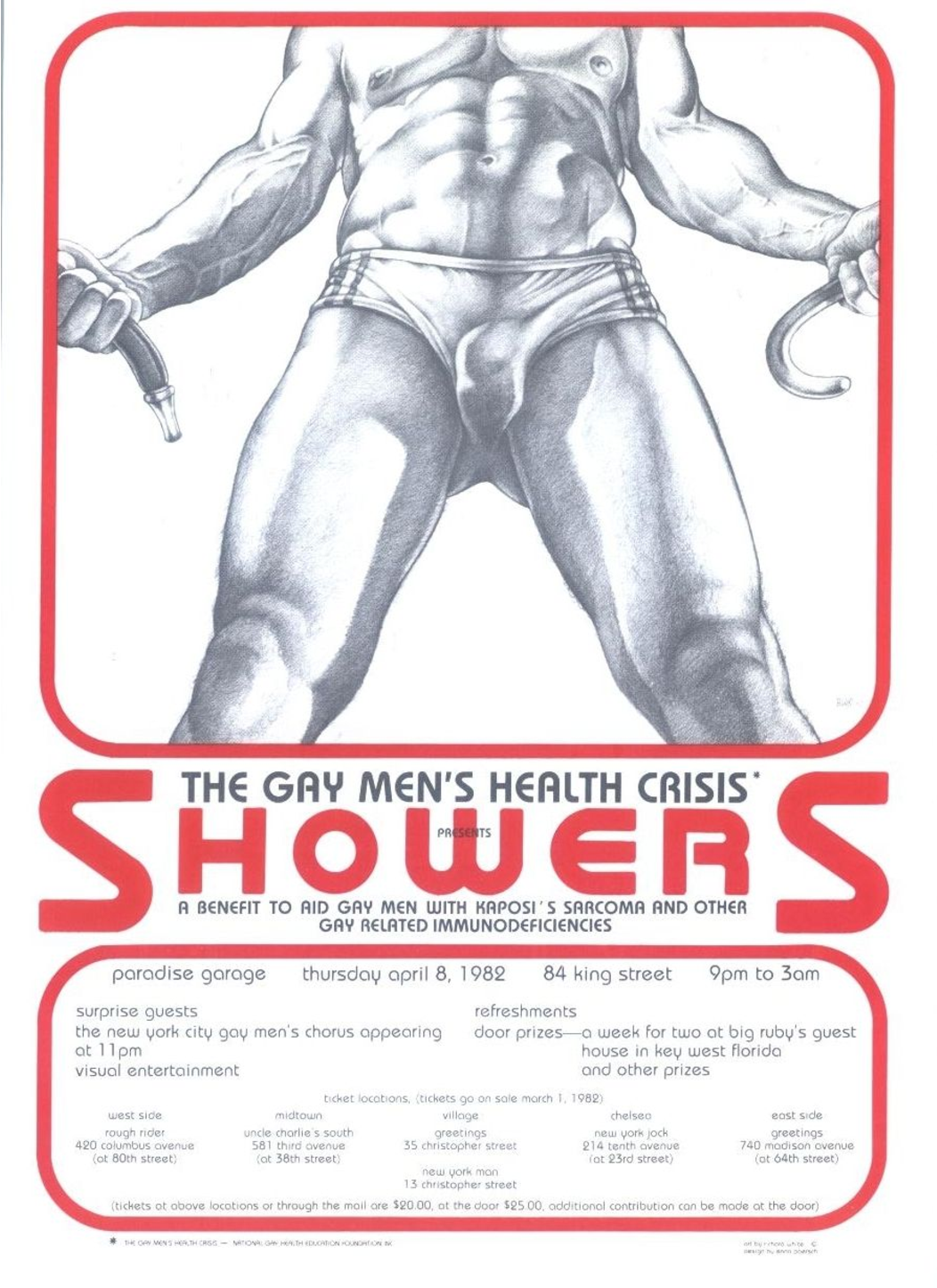

In April 1982, the recently formed Gay Men’s Health Crisis (GMHC) held its first fundraiser, called “April Showers”, at the Paradise Garage to face the then so-called “Gay Cancer” (HIV/AIDS). Courtesy GMHC.

M

Memory

The island of Puerto Rico may be a paradigm of the postcolony as defined by Achille Mbembe. Formerly a colony of the Spanish Crown and now unincorporated United States territory – one whose citizens, to this day, hold no voting rights – it is a place in a permanent state of crisis. In such a context, infectious diseases have been shaped and made worse by the asymmetries of power – as yellow fever in the 1800s or Zika and dengue in the 2010s illustrate. Public health has mostly served to further entrench and legitimise colonial control. This was the case with the campaign against hookworm launched by the US government in the wake of the 1898 invasion, which would inspire the activities of the Rockefeller Foundation. In the words of Sofia Gallisá Muriente, "those paying the debt adapt their eyes to the physical and mental exhaustion, the heat and humidity, the salt, mould, pollen and dust in the air; the uneven recovery, misshapen trees and layered catastrophes."

Sofia Gallisá Muriente, “Celaje”, 2020. Film still. Courtesy of the artist.

O

Origins

Over the past decade, new genetic research on HIV has pinned the origins of the virus to French and Belgian colonial presence in the Central African rainforest – and to the extractive economies that, in the early 20th century, transformed the landscape, social structures, and human-nonhuman contact. Such findings – which extended back in time the beginning of the pandemic and linked it explicitly to European colonialism – have implied a drastic rethinking of the temporal and geographic coordinates of HIV/AIDS. However, they also raise important questions about causation, the ontological status of scientific evidence, and the production of historical narratives in a context of colonial oppression and ongoing marginalisation.

P

Plants

One of the earliest viruses to be identified by modern science did not infect humans but flowers: the tulip breaking virus (TBV), first described in 1928. Before the discovery of the disease agent, infected blooms were valued because of the variegated effects of the virus, which produces flames and stripes of different colours. Once highly prized, "broken" varieties of tulip are now often destroyed; their cultivation is banned in places like the Netherlands, where the tulip industry is strong, as they are seen as a threat to the purity of native tulip breeds. A virus that has no negative effects on plants (nor on humans) but is nonetheless treated as a hazard can make us question the aesthetic terms in which plants are framed, as well as the words and metaphors we use to discuss contagion.

Michael Wang, “Extinct in New York”, 2019. Installation view. Courtesy of the artist.

Prophecies

In 2009, 51 cases of malaria were detected in Greece – thirty-five years after the disease's supposed eradication. The return of the disease was a consequence not just of the brutal austerity policies imposed on Southern European countries that drained healthcare spending, but of the racialisation of immigrant farm workers, who were exposed to mosquitoes while exploited in the fields. Only a few years earlier, in 2005, the United States saw large-scale preparations and alarm for an upcoming pandemic of H5N1 influenza originating in farmed poultry – a threat that, at the time, did not materialise. Epidemics can be all but ignored when they involve bodies considered as disposable – or trigger large-scale preparedness when they seem to threaten the body of the nation. Depending on who or what is seen as vulnerable, public health knowledge, protocols, and narratives operate in differential ways.

T

Travel

What does it mean to travel along with “others” in a vulnerable state? How could a symmetrical companionship between humans and non-humans be imagined? Is it possible to find ways of coexistence beyond the contemporary regulations that exclude and segregate bodies, communities, and environments? Contemporary traveling means being aware of environmental and political vulnerabilities. From masks to vaccine cards, from passports to other IDs, traveling is a multifaceted negotiation – whether by apprehending the invisible agents that populate the air, turning it into a complex infrastructure, or by being subjected to regimes that limit the possibility of crossing borders.

C+ arquitectas/In the Air, “Yellow Dust”, 2018. Installation view. Courtesy of Nerea Calvillo.

Treatments

Mafavuke Ngcobo was an herbalist active in Durban, South Africa, in the 1930s. He worked at the threshold of plant-based remedies and modern business practices – a combination that white medical practitioners saw as a threat. In 1940 Ngcobo was brought to trial for his practice, with the jury seeking to determine what constituted "native" medicinal plants – a definition that even at the time was far from settled. Eventually Ngcobo was forced to pay a fine. In the trial, African medicine was characterised as relying on simple processes and readily available plants, in contrast to the more "advanced" Western medicine. An instance of conflict with so-called traditional medical practices reveals how the domain of modern science was often imposed through racially determined claims of authority and rationality.

U

Urbanism

The Instituto de Higiene e Medicina Tropical was founded in Lisbon in 1902. Originally located on the Tejo riverfront in the buildings of the Cordoaria Nacional, it was moved in 1925 to its current location at Rua da Junqueira. Alcântara and Belém are the areas of Lisbon that bear the urban traces of the empire more than any other. The motto of the institute – Sanitatem quaerens in tropicos, "procuring health in the Tropics" – still reminds us of the colonial history of public health. The category of "Tropics" has historically been used to label entire parts of the world as infected, thus legitimising their exploitation. Much of the modern scientific knowledge of infectious diseases emerged in the colonies first, driven by the need to protect the health of European settlers and to govern the colonised. Such legacies remain scarcely examined in the public discourse, even as we stand in close proximity to their built traces.

W

Wildness

From zombies and falconry to Oscar Wilde and Max, Maurice Sendak’s beloved children’s book character, wildness escapes systems of classifications and normative taxonomies, Jack Halberstam explains. Many kinds of bodies have simply been cast as wild by civilisational and colonial discourses. By the late 19th century, the category of wildness was most often applied to racialised bodies. Counter-discourses began to appear by then, as narratives that commandeered the terrain of nature and the anti-natural to express a deep distrust of emergent normative medical, social, and political systems of knowledge. In the work of Halberstam, wildness is reframed as an emancipatory tool, radicalising knowledge and confronting confinements.

Himali Singh Soin, “Static Range”, 2020. Courtesy of the artist.

Andrea Bagnato has been researching architecture, ecology, and epidemiology since 2013, under the long-term project Terra Infecta https://andreabagnato.eu/terra-infecta. Among the project's outcomes are a book on infected landscapes in Mediterranean Italy (with Anna Positano; forthcoming by Humboldt Books), the book A Moving Border: Alpine Cartographies of Climate Change (with Marco Ferrari and Elisa Pasqual; Columbia/ZKM, 2019), as well as lectures and an essay series. Bagnato has been teaching on these subjects at Willem de Kooning Academy in Rotterdam and at the Architectural Association in London. As a book editor, he worked for the Sharjah Architecture Triennial, Forensic Architecture, and the Chicago Architecture Biennial.

Ivan L. Munuera is a New York-based scholar, critic, and curator working at the intersection of culture, technology, politics, and bodily practices in the modern period and on the global stage. In 2020, he was awarded the Harold W. Dodds Fellowship at Princeton University. He has curated exhibitions at Museo Reina Sofía (2009), Ludwig Museum (2010), and CA2M (2012-2013); and developed a series of projects, including The Restroom Pavilion / Your Restroom is a Battleground (Venice Architecture Biennale, 2021), “Bauhauswelle” (Floating University Berlin, 2018) and Chromanoids (Istanbul Design Biennale, 2016; Seoul Biennial of Architecture and Urbanism, 2017).

Vulnerable Beings builds on long-term research by Andrea Bagnato and Ivan L. Munuera which thinks about space and cohabitation through the lens of infectious diseases. In a two-part public assembly at maat – Tuning In (29–31/10/2021) and Sounding Out (26–28/11/2021), guests from different disciplines and backgrounds will come together for a dense sequence of lectures, dialogues, performances, screenings, and music. This is the first part of a multi-sited project curated by Andrea Bagnato and Ivan L. Munuera, which will continue with an exhibition opening in the summer 2022 at La Casa Encendida.