Interferences. Emerging Urban Cultures

Words by António Brito Guterres, Carla Cardoso and Alexandre Farto, curators of the exhibition

Informal tour to the exhibition programmed by Tristany with Fluor Scent (2022) by Obey SKTR on the back, presented as part of the Agenda of the exhibition Interferences. Emerging Urban Cultures (maat, 03/09/2022). Photo: Joana Linda, courtesy of EDP Foundation / maat.

|

Interferences introduces other sides to this city we live in, delving into the corners that we rarely see. It looks at the city’s diversity and the strength it represents, shining a light on the people and their stories in a segmented and antagonistic metropolis.

The cultural diversity that characterises Lisbon does not soften the many stories of a segmented and antagonistic metropolis. Interferences affirms different expressions of urban culture, exploring narrative itineraries of the city through dialogues that prioritise the museum as a critical space, a place where various communities and sensibilities come together – those part of the establishment who frequent it and those subordinate who are unfamiliar with it – as a starting point for new beginnings. The Museum of Art, Architecture and Technology (maat) has therefore become a platform for utopias and timeless struggles, for debating tensions, for stories told and those yet to be heard. Engaging with this theme in the museum does not mean interring it; rather, it reaffirms the theme’s topical nature, as suggested by the exhibition’s title, which echoes the moments of interference that we need or that have existed over time, such as the fire at the Galeria de Arte Moderna [Gallery of Modern Art] in Belém in 1981. The exhibition revisits the impact of this event, as a symbolic moment, to imagine alternative individual and collective trajectories.

The city’s design evinces inequality and stigmatisation, giving rise to demands for greater access, rights and visibility for the people and groups affected.

To stage those various aspects, we placed the work of artists who use the streets as a forum of expression and experimentation in dialogue with work by artists represented in private collections. This dialogue emphasises the alternative narratives that attempt to question visitors and to invite them to reflect on the city, urban spaces and cultural institutions that can be constructed by including new voices in this, often elitist, process of designing a city. By offering both a retrospective and contemporary gaze, Interferences can be defined as a contribution to a more plural approach to city design, therefore yielding space, the Agenda and the right of expression to a few more people.

The elements on exhibition and the programmed intangible events are there to decode absences. Nothing is definitive here. The exhibition is also organised like a cadavre exquis, setting space aside so that this dialogue can be augmented, through five months of workshops.

The exhibition itinerary intersects with the Agenda's different moments, with themed sections that are symbolically equivalent. These also function independently and generate dialogues with the exhibition’s core theme: the design of the city and its actors. Each section consists of different representation formats and exhibition elements comprising work by artists from emerging urban cultures and dialogues between existing pieces (or works in process, in some cases actually in the exhibition) from formal institutional and informal urban spaces. The aim is to ensure an interlinked holistic experience and to guarantee a variety of approaches throughout the exhibition.

|

|

|

Views of Bandeiras (2022) by Unidigrazz with Hinu Digra (2020) by Tristany playing in the background in the exhibition Interferences. Emerging Urban Cultures. (maat, 30/03–05/09/2022). Photo: Bruno Lopes, courtesy of Underdogs. |

|

Partial view of the exhibition Interferences. Emerging Urban Cultures (maat, 30/03–05/09/2022). Photo: Bruno Lopes, courtesy of Underdogs.

Photos by Julião Sarmento of the fire at the National Gallery of Modern Art, Lisbon, 1981, included in Interferences. Emerging Urban Cultures (maat, 30/03–05/09/2022). Photo: Bruno Lopes, courtesy of Underdogs.

Against the Muteness

of Walls

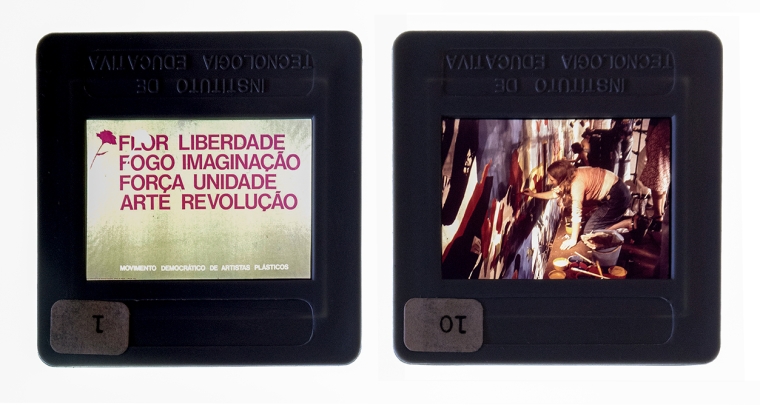

In the immediate aftermath of the Carnation Revolution there was a strong collective process of artistic production. The mural, painted on 10 June 1974 at the National Gallery of Modern Art, in Belém, is an example of this.

The cities reverberated the effervescence of a moment that was characterised by a renewal of words and aesthetics against the muteness of the walls. But the restlessness of the times also called for a renewal of the spaces, their uses and appropriations, it called for democratic places for everyone.

The mural disappeared, consumed by flames in the fire that destroyed the gallery, and this event stands as a metaphor of what was left undone, a project postponed. Even in a period that appreciated the pleasures of expression, some stories were left unappreciated: the importance of the liberation movements in the assertion of spaces of freedom in the former metropolis.

The mobilisation of the Portuguese for the war, and all those who escaped it by fleeing to other European countries, gave rise to the concept of “contracted workers”, mainly brought in from Cape Verde to balance out the lack of manpower, particularly in Lisbon’s public works.

A new metropolis began to take shape.

After the Carnation Revolution, in the 1970s, but also throughout the ‘80s and ‘90s, a new wave of immigrants, coming mostly from Africa, started becoming residents of the new metropolis. Lisbon already had its African communities and there is markedly an African influence in its founding matrix, resulting from those who were first brought as slaves (and then freed), but this was a new surge adding thousands to the city.

The great majority of these immigrants settled on the outskirts of the city, which grew to be more and more segregated, gaining colonial contours in a post-colonial era.

The welcoming of these people had different contours and layers. In 1981 a new nationality law barred the new generations from gaining Portuguese citizenship. In police reports and in the press, the association between these residents and crime and unlawfulness became normalised.

Luso-tropicalism was not an inheritance, it was in force and, in the midst of this belief, Alcindo Monteiro was murdered in the centre of Lisbon by a group of skinheads.

As a voice of a generation, hip-hop was one of the first expressions of resistance coming from the city outskirts.

The voids, the concealments, the misrepresentations were so many that even today many are dedicated to an ontology that registers the presence of their bodies in this territory.

|

|

Works by Petra Preta. From left to right, from top to bottom: “A cultura é a festa da imaginação produzida pela luta. Esta luta é um trabalho coletivo, organizado”, 2021, Fake it till you make it, 2021, For all of us / this instant and this triumph / we were never meant to survive, 2021, Sobre “encenar a negritude”, 2021, and Untitled, 2021, in the exhibition Interferences. Emerging Urban Cultures (maat, 30/03–05/09/2022). Photo: Bruno Lopes, courtesy of Underdogs. |

|

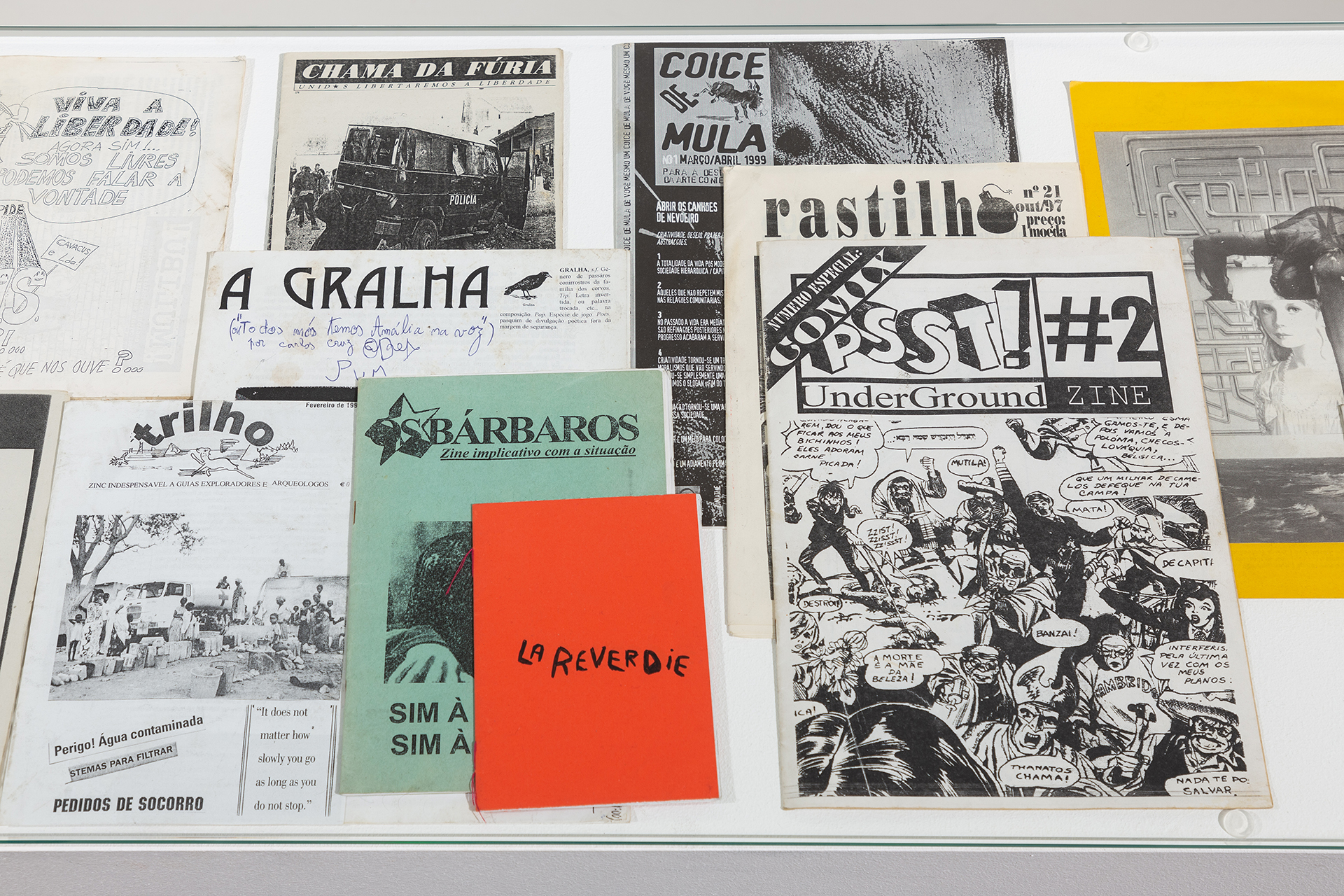

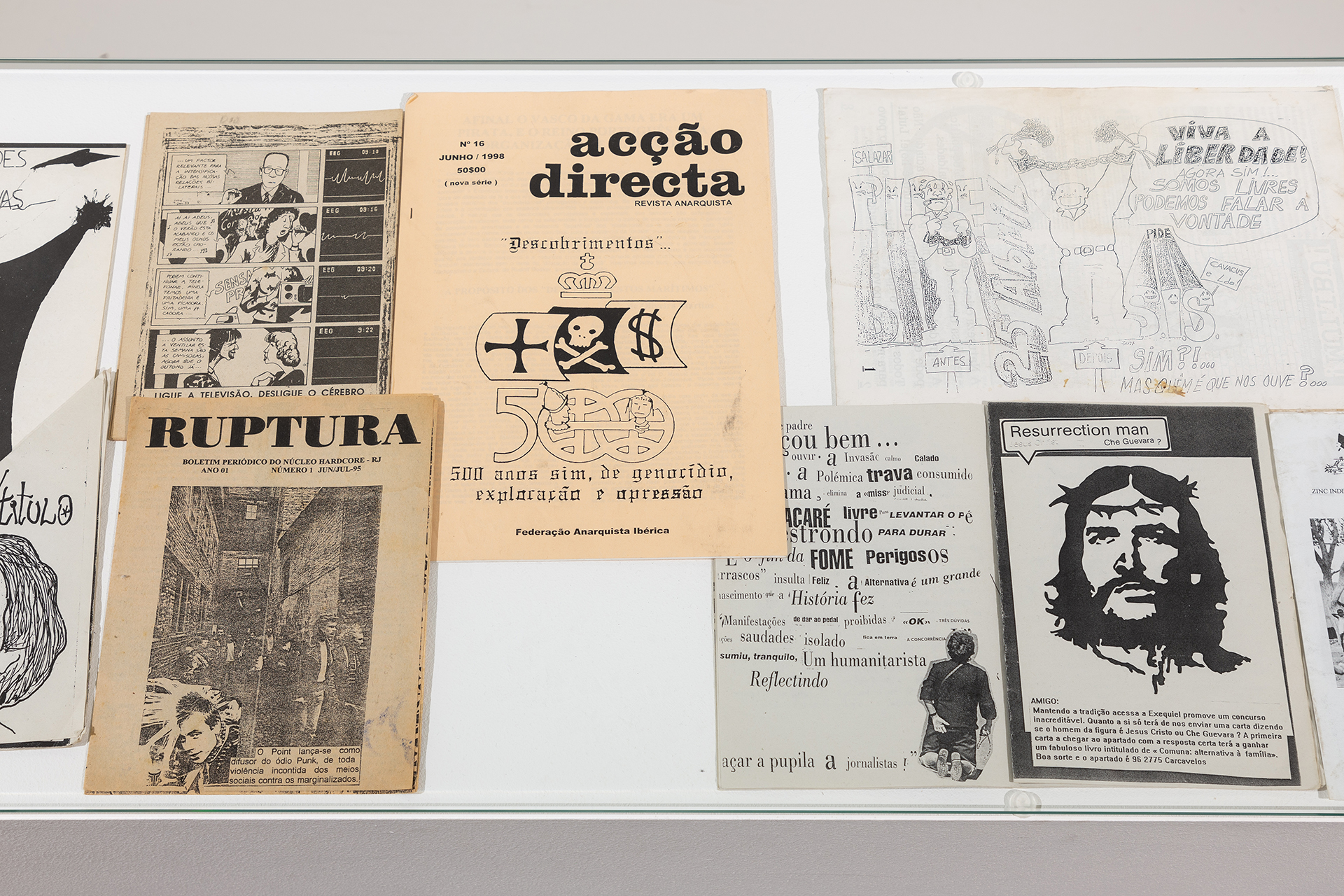

During a long period of what was still a young democracy, the scarcity of institutional artistic spaces, especially representative spaces, meant that absences and concealments were only broken up by low-cost and informal publications – fanzines – which, together with the streets, walls, and trains, constituted for many years the space for expressing many sensibilities. Selection of fanzines presented in the exhibition Interferences. Emerging Urban Cultures (maat, 30/03–05/09/2022). Photo: Bruno Lopes, courtesy of Underdogs. |

|

|

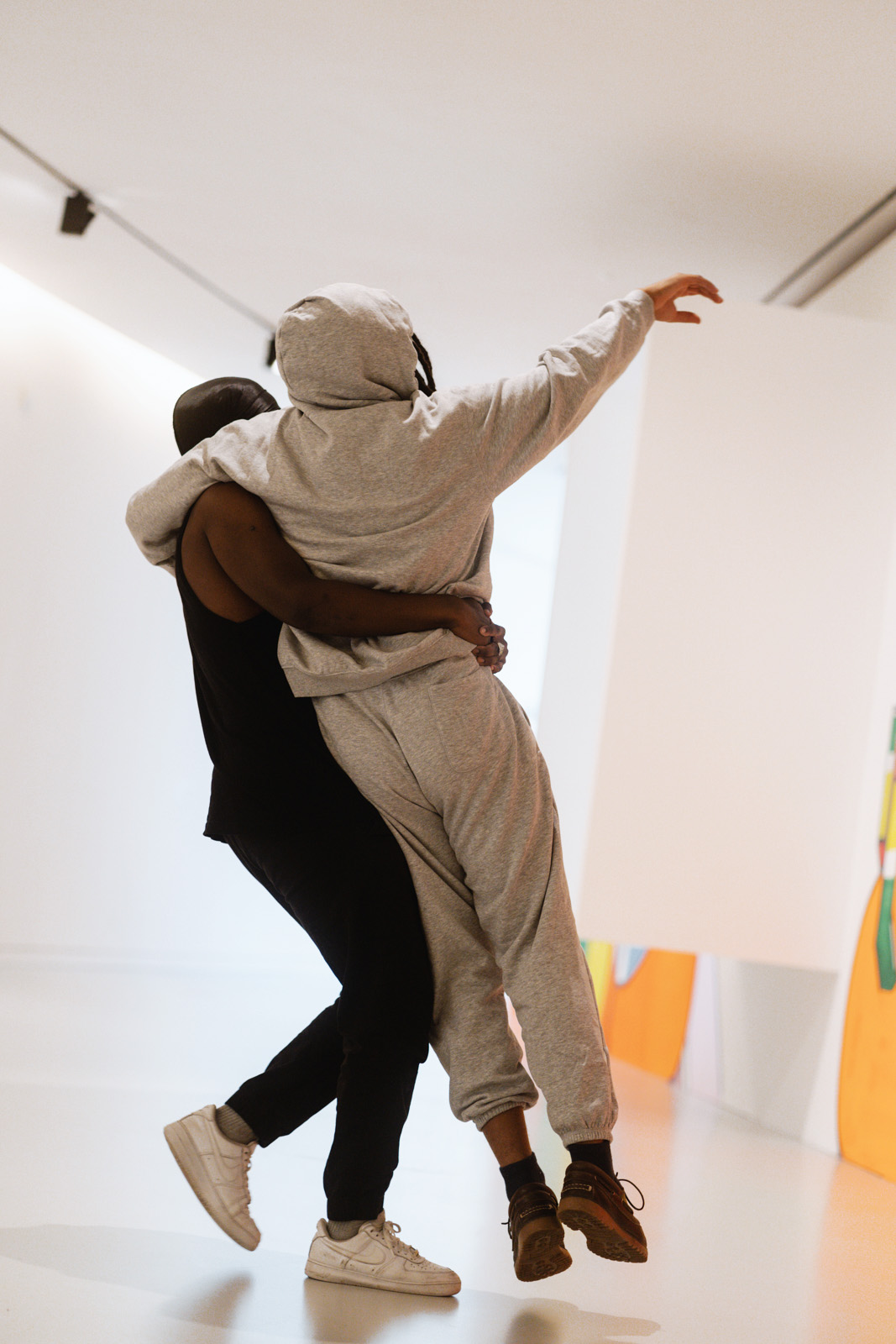

Performance by Filipa Bossuet in Interferences. Emerging Urban Cultures (maat, 03/09/2022). Photo: Joana Linda, courtesy of EDP Foundation / maat.

An immersion in the artist’s existence from her physical and mental space: the bedroom. The title derives from an expression in the Kikongo language that was conveyed to her by her father, who is Bakongo. It deals with the unforeseen aspects of life, our unplanned experiences, and what we can learn from them. The installation was complemented by a series of performances that reflected on the place of discomfort of the black body. Filipa Bossuet’s Mankaka Kadi Konda Ko, 2022, in the exhibition Interferences. Emerging Urban Cultures (maat, 30/03–05/09/2022). Photo: Bruno Lopes, courtesy of Underdogs.

City Design

In this chronology of the city, there is a city that followed the plan and another without a plan, or rather, with other plans. Many of the new immigrants arriving in the Lisbon Metropolitan Area – migrants who suffered the indignities of precarious labour, racism, speculative rents, and denial of a path to citizenship or residence permit – resorted to informal settlements on the edge of the city, between municipalities and close to industrial areas, to build their homes there.

First built from precarious materials, the houses were progressively improved, often in secret, at night and inside a temporary façade. Many new neighbourhoods were built that way, and would become part of Lisbon’s ecology, not very different from those built in previous decades by the migrants coming from rural Portugal.

Ten years after joining the EEC, many economic transformations were already noticeable in Lisbon, a city now much more oriented towards the tertiary sector. This period coincided with the design of a new generation of housing policies, including the Special Rehousing Plan.

New neighbourhoods were thus built, denser, higher. A new life that should have coincided with other rights: access to employment, to education, to desire.

It was soon realised that that would not be the case.

|

|

Primero G, 100nhos, 2009. Directed by Primero G |

As it grew, it was also labelled. From the production of the various discourses: from the police forces, the press, and commonplaces. The municipalities categorised some of their territories with diverse stylistic resources: sensitive zones, priority neighbourhoods, critical neighbourhoods, challenging territories, problematic neighbourhoods. Almost all the territories marked by the municipalities are inhabited by those who massively migrated to the city, either due to internal processes– rural exodus – or to external processes. In the dehumanisation of those contexts, their inhabitants respond with new geographies and differentiated denominations, namely postcodes. Ana Teresa Ascensão and António Brito Guterres, Lisboa Etiquetada, 2022, in the exhibition Interferences. Emerging Urban Cultures (maat, 30/03–05/09/2022). Photo: Bruno Lopes, courtesy of Underdogs.

Rodrigo Oliveira, Colapso (Escultura Inflamável #2), 2005, in the exhibition Interferences. Emerging Urban Cultures (maat, 30/03–05/09/2022). Photo: Bruno Lopes, courtesy of Underdogs.

Common

The inhabitants of the Lisbon Metropolitan Area who live in self-built or social housing neighbourhoods are, for the most part, descendants of the most recent migratory waves that flowed into the city, both from rural Portugal and from countries that once had a colonial relationship with Portugal.

Deprived from the full exercise of their constitutional rights – in some cases without a path to citizenship – and in the face of general public disinterest, many of these residents self-organised to create a space of belonging: the right to a place.

Informal social security schemes were created, Djunta Mon allowed for the construction of houses and collective facilities, and nanny networks, urban vegetable gardens, and music studios were created. This was a place created on a foundation of belonging, disconnected from a public policy that was incapable of reaching out to this reality and its many forms.

|

Carlos Bunga, Arquivo, 2022, with works by Herberto Smith behind it in the exhibition Interferences. Emerging Urban Cultures (maat, 30/03–05/09/2022). Photo: Bruno Lopes, courtesy of Underdogs. |

|

Photos by Marta Pina in the exhibition Interferences. Emerging Urban Cultures (maat, 30/03–05/09/2022). Photo: Bruno Lopes, courtesy of Underdogs. Row 1, from left to right: PML Beatz, 2019, Puto Tito, 2019, Firmeza, 2016, Cucena, 2014, Marlon, 2016, Nídia, 2016; row 2, from left to right: Tia Maria, 2019, Rogério, 2019, Zona Não Vigiada, 2016, Rogério, 2015, Lumiar, 2015, Firmeza, 2015; row 3, from left to right: Nídia, 2019, Blacksea Não Maya, 2020, Nervoso e Eddy, 2014, Noite Príncipe, 2015, Nídia, 2016, Chelas, 2016, Pendão, 2015; row 4, from left to right: Rogério, 2021, RS Produções, 2019, Noite Príncipe, 2014, Lisboa, 2017, Normal Nada, 2015, Lumiar, 2015.

Network City

From the middle of the first decade of the 21st century, easy access to computers, the Internet, and wireless technologies – first through digital inclusion initiatives and later through individual acquisition – made it possible for the inhabitants of the peripheries of Lisbon to have free access to software that enabled them to create and disseminate their artistic productions (especially in music). Thus, in a fragmented city with a single centre, which was symbolically difficult to access, an online network of cultural affections was created. It was not valued by the city’s institutions, but it allowed the creation of an urban scene that was more representative of the city’s real face.

Parallel to the consolidated structures, a network of cultural diffusion and expression emerged. Slowly, although still far from a place of reason, some elements, including actors and forms, crossed once forbidding borders.

The Unidigrazz collective emerged in 2017 in the Mem Martins (Sintra) area, aggregating a number of multidisciplinary artists: musicians, photographers, illustrators, filmmakers, and graffiti writers. Shaped by their life experiences in group in the Sintra Line, and armed with a sense of self-communion, the collective artistically expresses the social fabric that lives on the fringes of Lisbon, in peripheral cities where inequalities prevail on every corner. The collective includes, among others, the members Diogo “Gazella” Carvalho, Onun, Trigueiros, Rappepa bedju tempu, Sepher AWK, and Tristany. Installation by Unidigrazz in the exhibition Interferences. Emerging Urban Cultures (maat, 30/03–05/09/2022). Photo: Bruno Lopes, courtesy of Underdogs.

|

|

Us by Us

For many years, the history of urban expansion was reported by those who had access to the means of production and communication, players who were often external observers of a reality with whom they did not engage.

The artistic and cultural life of these peripheral places, although existent, was virtually absent from the formal means of production and exhibition.

After the revolution, precious murals helped to vindicate the housing problems of some peripheral neighbourhoods and, two decades later, graffiti broke through the city claiming new presences, aesthetics, and ways of living.

Gradually, and knowing that much has been lost along the way, the new generations from these peripheries are tearing up these deadlocks and exposing their ways of seeing, understanding, and living the city in various languages.

“The once considered vandal, the non-artist, is finally allowed in the museum, in the gallery… Hesitant, he feels the weight on his shoulders – on the one hand, the doubt of institutionalised reality that can no longer ignore him, so visible is his presence; on the other, the expectation of his peers who see him as their representative. True to himself, he decides to do what he knows best, what he always wanted to do when allowed to paint in the museum: to bring graffiti to this stage in all its magnitude and essence. Using all the characteristic elements of graff, he paints a burner, the designation for a piece equipped with all the accessories to win a battle of styles in the hall of fame: letters, arrows, stars, dimensions, depth, tags, glows, highlights. Nothing is missing from this King piece.” – Obey SKTR. The mural Fluor Scent, 2022, by Obey SKTR in the exhibition Interferences. Emerging Urban Cultures (maat, 30/03–05/09/2022). Photo: Bruno Lopes, courtesy of Underdogs.

The Right to Imagine

This journey ends with the right to imagination, as a space for everyone, a proposal of a future (which should have been past and present), of freedom for the idiosyncratic voices that are still being held back just because of the place they were born and live in the city.

When freed from these spaces of oppression: defined by territory, gender, or race… these authors have room to imagine new cities, new places of community and artistic proposals that contribute to the collective imagination and cultural diversity. (…)

Civic institutions such as museums, galleries, community art organisations, but also municipalities and the political agents who decide national representations in international biennials, now have a rare opportunity to lead by choosing to collaborate with artists who have been underrepresented. The engagement of specific groups can help to design and conduct creative community programmes to build more diverse cities, neighbourhoods, and artistic collections.

But it is not always necessary for institutions to act. The works presented here offer inspiring examples of how artists and communities can make a difference in our collective imagination.

|

|

Performance by Herlander presented as part of the Agenda of the exhibition Interferences. Emerging Urban Cultures (maat, 03/09/2022). Photo: Joana Linda, courtesy of EDP Foundation / maat. |

Mantraste e moradores do PER 11, Cria Futuro, 2021, in the exhibition Interferences. Emerging Urban Cultures (maat, 30/03–05/09/2022). Photo: Bruno Lopes, courtesy of Underdogs.

View of “Monument” special section in exhibition Interferences. Emerging Urban Cultures (maat, 30/03–05/09/2022). Photo: Bruno Lopes, courtesy of Underdogs.

Monument

There are issues that, even following the change of regime, remained sacred in the public space, virtually undebated, adverse to new discourses. From provisional to definitive, and thus it seemed to remain – but in the relationship between the body and the stone, nothing is definitive.

In the absence of a diversity of representative stories in the public space, in a city institutionally removed from its mosaic, the Monument exerts a special attraction in the inventory of other ways of seeing the world and, internally, of society itself.

In a way, how the Monument to the Discoveries has been regarded, has reflected –throughout the entire period of democracy – in a denser and closer way to the current chronology the various life experiences of the city and its sensibilities.

This special nucleus proposes the legitimation of artistic creation as a privileged means to debate the city, reflecting on the uses of public space with various meanings and symbology.

|

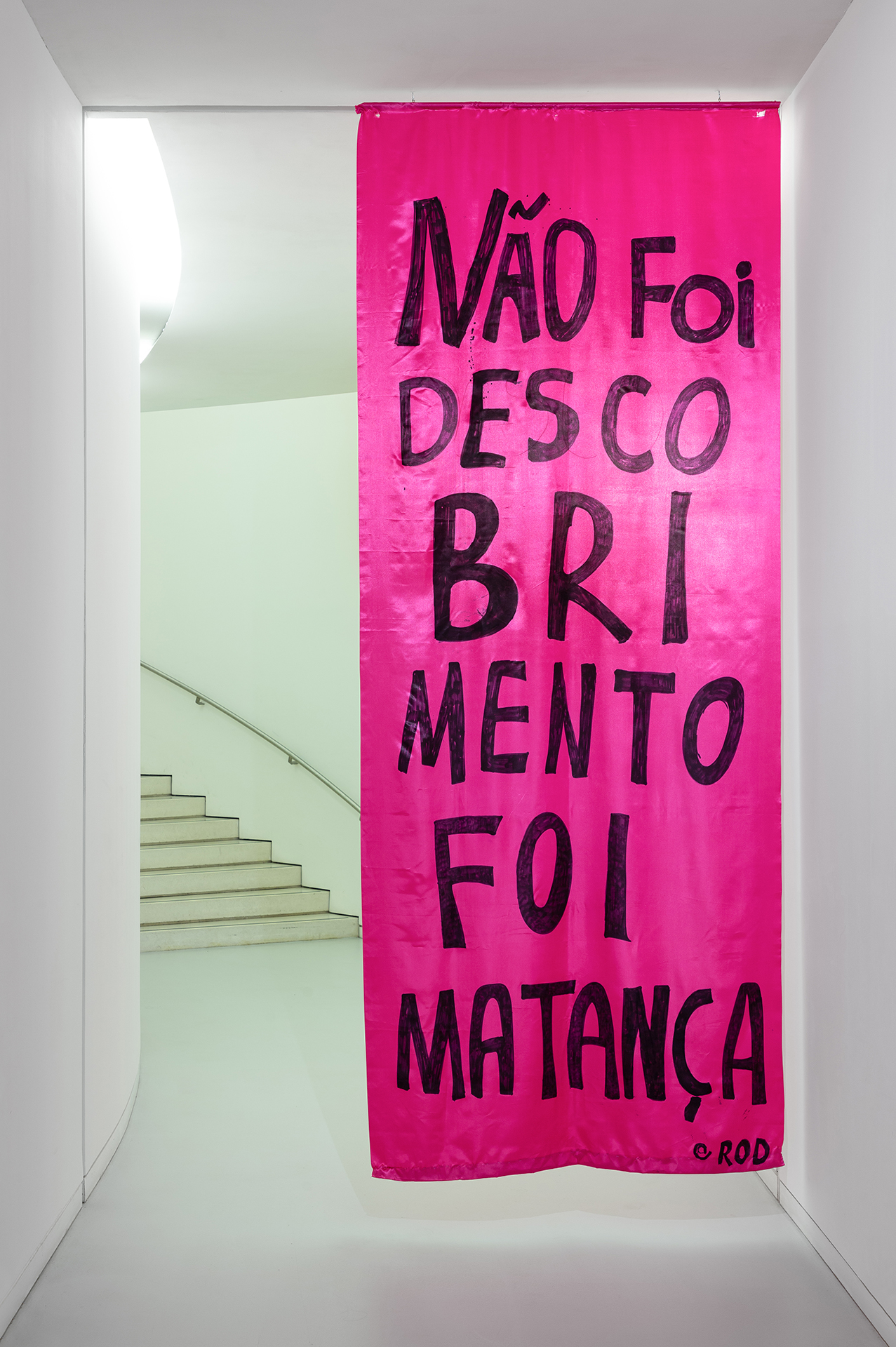

ROD, Pink Flag, 2021, in the exhibition Interferences. Emerging Urban Cultures (maat, 30/03–05/09/2022). Photo: Bruno Lopes, courtesy of Underdogs. |

The cultural diversity that characterises Lisbon does not soften the many stories of a segmented and antagonistic metropolis. Interferences: Emerging Urban Cultures (maat, 30/03–05/09/2022) is a group exhibition that affirms different expressions of urban culture, exploring narrative itineraries of the city in a conversation that prioritises the museum as a critical space where various communities and sensibilities come together as a starting point for new beginnings. Curated by Carla Cardoso, Alexandre Farto and António Brito Guterres, the exhibition is organised by sections addressing various themes that provide the tagline for a programme of events which will contribute to the exhibition’s narrative, some of them generating contributions that will be incorporated into it, making it a dynamic project that reveals itself to the public over the course of six months.

All texts were selected from the Interferences. Emerging Urban Cultures exhibition guide and catalogue.