The 10 June Mural or the Passage to the Act

by Ernesto de Sousa

Originally published in the Portuguese magazine Colóquio/Artes, in 1974.

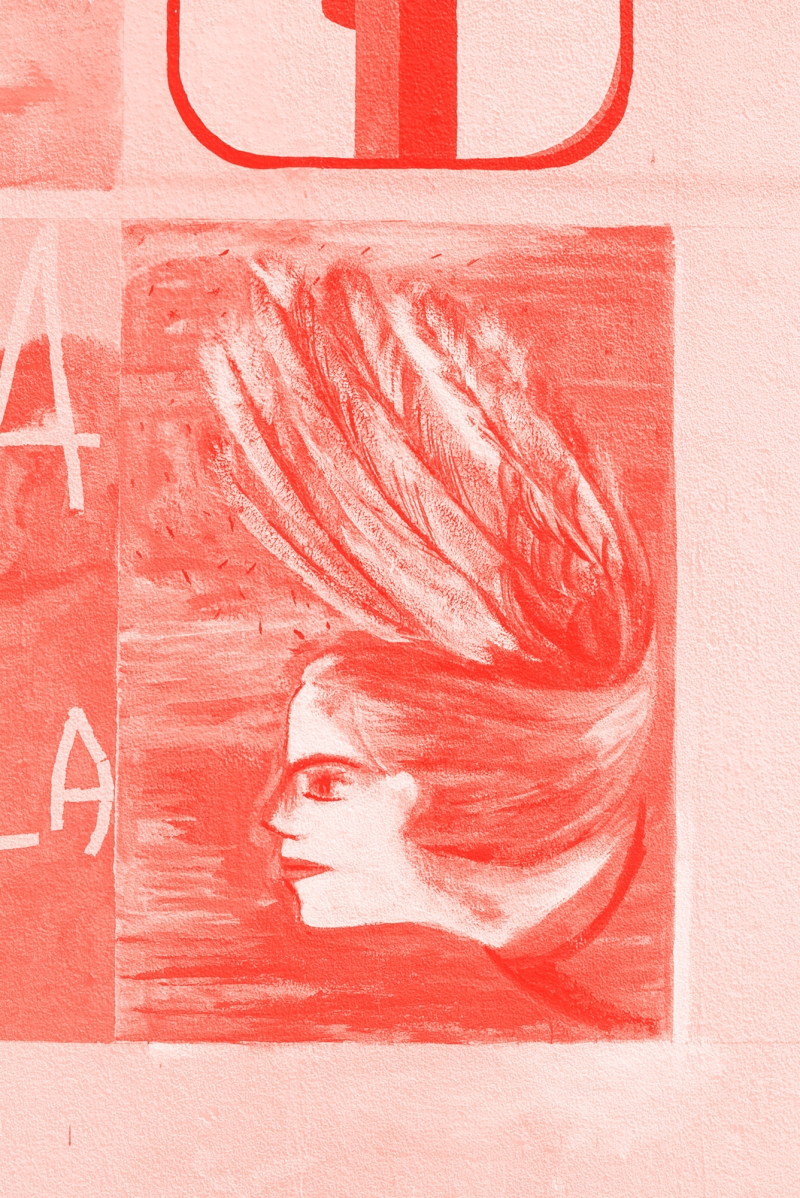

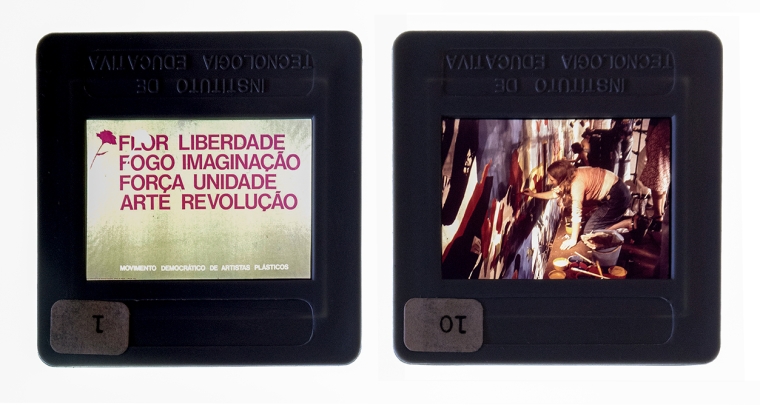

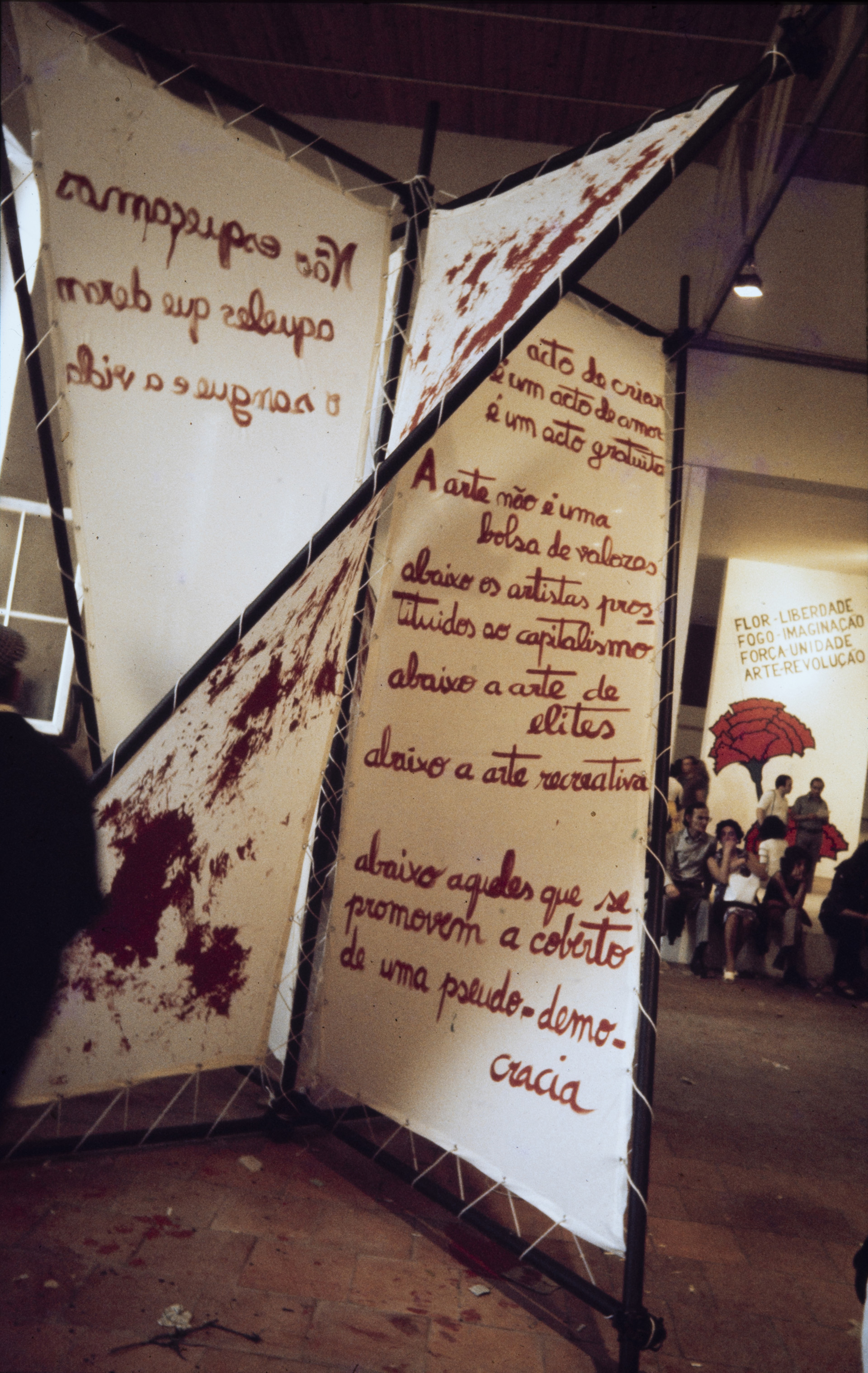

Celebration of the 10 June 1974: painting on the collective mural of the Movimento Democrático dos Artistas Plásticos, at the Mercado do Povo in Belém, 1974. Photo: Ernesto de Sousa (1921–1988). Courtesy of Câmara Municipal de Lisboa, Divisão Arquivo Municipal/Fotográfico (PT/AMLSB/ESO/001610).

If the “machinery of the passage to the act” did not entail a discursive novelty over and above its respective components, even as these have been distributed from the academy to the most debatable vanguard; if that mode, in its Lacanian sense, “according to which knowledge is distinguishable from its stereotypes” were not able to constitute evidence of another function ready to reveal or enrich; if...

... it would not be worth commenting about the “Belém mural,” or mentioning the “Spring Market,” or “The Movement of Democratic Artists,” over and above the respective assumptions and intentions; over and above a collective will of opportune and opportunistic affirmation, politically belated, contradictory even outside of the territory of the respective proof they offer, and above all...

... poorly additive, metaphor and catastrophe of a nation, a culture and a burden, a joy in reverse, “erased and vile sadness.” Concerning the assumptions, repeat.

(And this does not assume any pre-existing and pejorative judgements concerning people or the promoters, people and situations. Quite to the contrary. And precisely because in many there is generosity, and even generosity without anyone being a wise-crack along with it, oh Almada [Negreiros], and others too – it's because of all this that we can speak of metaphor and catastrophe. From a profoundly incapacitated group to thinking in accordance with a group problematic, the dramatic evidence of a nation of individuals and atoms with no intimate sense of coherence among them, no structure, nothing of what others might call soul or spirit. A group that condemns itself, that hasn't much self-respect when everything is attributed to paternal deficiencies or maternal lack; this all lamentably creeps along and intensifies in a worrying stereotype of shirked responsibility. Stereotype of the slave: forty-eight years of oppression ostensibly justify forty-eight years of toeing the line, and, as a matter of fact, of indifference and domesticated egoism. The logic of the stereotype: the future, a further forty-eight years of indifference, egoism, conformity, the excuses of someone who does not pay up, domesticity and slavish following? It is precisely because this could easily happen that severity imposes itself, while running the risk of injuring here and there some of the particulars that a methodical analysis would place outside of this context of responsibilities. This is necessarily the case with very young operators or interventionists, or with young intervention in the process. If they are not yet assured of the kingdom of heaven, they are also not yet truly responsible, somewhere along the spectrum of responsibility. The most that can be said is that they are heading in that direction.)

General view of the painting of the collective mural. Photo: Ernesto de Sousa. Courtesy of CML, DAM/F (PT/AMLSB/ESO/001595).

The painter Fátima Vaz (1946–1992). Photo: Ernesto de Sousa. Courtesy of CML, DAM/F (PT/AMLSB/ESO/001632).

|

|

The painter Teresa Magalhães (1944). Photo: Ernesto de Sousa. Courtesy of CML, DAM/F (PT/AMLSB/ESO/001609).

... it was a case of creating “a festival of joy.”

... it wouldn't be worthwhile. But the machinery of the passage to act contains more than the act properly speaking, or its trace in this vale of tears – painting. In short, everything has been said in the testimony of a young artist; and for this, his lucidity, it seems that there is no walking “beyond.” Let us see his words, almost in full. (And yes, take note of the name: António Mendes. He has not yet been promised the kingdom of heaven, and this record will hardly serve in his future accounts, with its as-yet-undiscovered arithmetic.)

Testimony:

“To explain my approach ... I think it is important to mention how the idea arose. It was on 1 May, out in the street, when a group of painters, recalling an experience some of them had recently had in Cuba, suggested that they paint the walls of the [Instituto Superior] Técnico. Because those walls were ugly, and they felt like making things beautiful; because now was the time for each of them to speak out, to do what he did best, out in the open and in everyone's view. And so, the painters were going to paint, and if there were musicians and actors and others who wanted to join them, they were welcome.”

And in conclusion: it was a case of creating “a festival of joy.”

... and it is here that the word festa – a festival or celebration – appears for the first time, or at least the idea of it. Here the machinery of the passage to the act begins to reveal itself. And even if the initial idea got stuck, the celebration could not be avoided, neither could the formalism of profound contradictions impede it ... nor the entropy of theories and assumptions. The “drawings for the people” were overtaken by the festival of the people. May it reveal itself to be explosive, cathartic like all true celebrations ... But let us not continue. Let us rather follow again the discursive thread of António Mendes.

“Then came the organisation phase ... and when we took notice (at least when I paid attention), it was far from how it had begun. And I, who had adhered to a pure diversion, a party, found myself burdened with a serious ‘homage’ ...”

... “that no longer took place in sunshine, but in a closed space”...

... “that was not the simple covering of an empty wall but the painting of a conventional canvas”...

... “that was no longer a spontaneous manifestation, but an official celebration advertised by all the organs of information.”

I permit myself to highlight these three elements from the young painter's discourse because they contain an essential aspect of critique not only of the act, but also of the finished “work.” Closed space, conventional support, celebration and reverence, guaranteed publicity. And further, considering the most circumstantial aspects, António Mendes mentions the restrictive nature of it:

“to base a manifestation of joy on the grievances and hostilities of third parties is absurd.”

Let us emphasise, in passing, the pertinence of this observation, confirmed by certain recent arguments, articles and testimonies.

“And so, when I went, I did so unwillingly . . .”

And in the meanwhile:

“But the celebration did take place, and I think it turned out better than might have been expected . . . there was an unexpectedly festive atmosphere, brutally cut short – that much is true – by the scene of TV censorship that we all know about.”

Magnificent observation! The “work” was made, which for one – and independently of any reservations one might have – is clearly a virtue. The “work” has inevitable characteristics and limitations: a conventional canvas not acknowledging its own space, a space that neither is nor belongs to any architecture and that is, therefore, functionally absurd, apart from its obvious and ephemeral celebratory nature; the sum of disparate responses serving as a metaphor for a group of people incapable of working as a group. But through the machinery of the passage to the act, the “work” exposed itself as being celebratory. A Celebration.

A second mural, this one with the participation of the public. Photo: Ernesto de Sousa (1921–1988). Courtesy of CML, DAM/F (PT/AMLSB/ESO/001614).

The painter José Escada (1934–1980). Photo: Ernesto de Sousa. Courtesy of CML, DAM/F (PT/AMLSB/ESO/001623).

Sculpture by José Aurélio (1938). Photo: Ernesto de Sousa. Courtesy of CML, DAM/F (PT/AMLSB/ESO/001602)

Sculpture by Clara Semide (1943). Photo: Ernesto de Sousa. Courtesy of CML, DAM/F (PT/AMLSB/ESO/001622).

|

|

No contradiction in sight. It is, however, essential to add that the celebration was made up of other components, the distribution of which, in the final count, is not easy to establish. A coffin cast into the Tagus, the burial of fascism; the “heroic” songs of Lopes Graça; a space intended for painting by each-and-every-one; the “silencing” of the Comuna Theatre, and so many other demonstrations, in addition obviously to the sweat of artists' brows, the “beautiful” spectacle of their comings and goings up and down enormous scaffolding, visited by ministers and other celebrities, the hither and thither of an incipient democracy and the representation of innocence and furthermore the general and particular apparatus of TV cameras and their images refracted everywhere by monitors. In all this, perhaps the most important thing will have been the beautiful and important theatre of the Comuna and the TV reportage – as the facts have come to verify. As an aside, concerning theatre in general and the Comuna Theatre in particular: these are people who did not expect any April Revolution to intervene; no one here cared about paternal tyranny to assert their non-conformity. This happened from the outset; at least from the time of Gil Vicente ...

Let us continue with the words of António Mendes, following its discursive thread:

“I hope, in the meanwhile, that this has not only been a celebration in which a more-or-less successful panel was made, but an opening of pathways ushering in other endeavours of this type, in which artists go out into the streets, making things, mingling with life. And by this, I do not mean an art for the people ... Art for the people, no! Artists for the people – yes!”

Art for the people, drawings for the people.

“Stop playing with conceptual art, make art for the people!”

Thus, two concepts might be summarised; concepts that, notwithstanding the good faith in which they were proclaimed, I shall not hesitate to categorise as retrograde and confusing.

In these matters, faith is not enough, neither are the most various of good intentions.

Or at least, neither faith alone, nor good intentions by themselves. The greater the accountability, the greater the sense of responsibility fostered by the situation, the more cautious and, I would say, scientific should the public interventions be, whether they are slogans, articles, speeches or drawing ... We are no longer in 1945, in the middle of the century, a period marked by a certain romantic innocence and purity, by pamphleteering words, by an art form that still considered itself to be destined to unfurl in the winds of history. Now, things are what they are – they are what they truly are, as Brecht would have it.

A flag is a flag; a magnificent Cuban poster is a magnificent Cuban poster; and the probing and questing of art (truly of our time, truly of the vanguard) are what they are: probing and questing, as necessary and indispensable as the research undertaken under the banner of the natural and humanistic social sciences.

In all this, there are two concepts that need to be tucked away out of reach, where children and other innocents won't reach them, on the shelves reserved for poisons and other drugs.

First, the idea of art for the people. It's a patronising, petit-bourgeois notion; there's no point detaining ourselves there.

The second is more serious. To think that the arts of the vanguard (to group them all together as conceptual is pure ignorance) are futile and distant from “the people” is to mystify the widespread sense of this agglomeration of enquiries and trajectories that Mário Pedroso dubbed postmodern: a global phenomenon that, precisely, counters the “objective” nature of pseudo-modern art, the kind intended for external contemplation, for the maintenance of the figure of the artist as a privileged and elitist being; for the widening of the gulf between spectacle and spectator. This is a global phenomenon, a call to participation, an invitation to an aesthetic act more than an aesthetic object, made for all. It is, precisely, with this set of measures that strictly conceptual explorations reveal themselves as the exception, a little like the linguistic research, in a kind of wild-state semiotics – but let's not get into details here.

The painter Nikias Skapinakis (1931–2020). Photo: Ernesto de Sousa. Courtesy of CML, DAM/F (PT/AMLSB/ESO/001612).

Painting by Henrique Manuel (1945–1993). Photo: Ernesto de Sousa. Courtesy of CML, DAM/F (PT/AMLSB/ESO/001634).

|

|

In general, the modern Portuguese painters are modern and not postmodern, and “proudly alone,” (→ 1) they turn their backs on actual contemporary research, clinging onto the antiquated concepts of “finish” and craftsmanship, fetishising the trace of the artist's hand which, of course, dovetails perfectly with what the market wants. The exceptions are few and far between, and frequently heroic. As for the Belém “mural” (which is no mural at all), there is nothing heroic about the theoretical precepts that underpin it, while its execution – its passage to the act – has been worthy and skilful, extremely agreeable. As has already been said, the fact that the underlying principles offer themselves up as spectacle does not bring the creative act any closer to the “public.” On the contrary. If artists have presented themselves as spectacle, which is pleasant enough, the distance between stage and stalls has still not diminished. They've made figurines for the people in sight of the people. And this has happened even for those operators in whom the principle of research may be glimpsed, through the additive character of “visible skill” that infects them.

Is this to say that the “mural” is of no interest? Not at all. It may be of minor interest, but it is not insignificant, the outcome of the agglomeration of various parts that, separately, are more or less sound (and such an analysis would be an interesting challenge), the truth is that the whole appears to be larger than the sum of its parts. Over and above the initial assumption, the “mural” reveals an unexpectedly festive character. Thinking arithmetically, this might seem paradoxical. But in effect, Lacan's observation, quoted at the outset, is applicable here. The machinery of the passage to the act might offer enrichment that is not limited in its stereotypes. In other words, while neither its underlying assumptions nor its constituent parts are truly modern (there might even be real regression here), the whole emerges as sufficiently well positioned to assume the mantle of the postmodern. That being the case, the meaning of this passage to the act would be a truly interesting object of study for painters to take on board, leaving aside vanity and factionalism.

This text was originally published in Portuguese, with the title “O Mural de 10 de Junho ou a Passagem ao Acto” in the magazine Colóquio/Artes, no. 19 (October 1974), Fundação Calouste Gulbenkian, Lisbon, pp. 44–47.

Translation by Ruth Rosengarten.

-

(1) Translator's note: “Proudly alone” was a famous expression used by the Portuguese fascist dictator António de Oliveira Salazar in a speech made on 18 February 1965, to describe the Portuguese offensive in the African colonies at a time when the rest of the world was already in the process of decolonisation.

Ernesto de Sousa (Portugal, 1921–1988) was one of the most complex and active figures of his time, a prolific multidisciplinary artist and an avid producer of synergies between generations of artists from both the first and the second half of the 20th century. Defending an experimental and free artistic expression, he dedicated himself to the study, promotion and practice of the arts, as well as to curatorship, critique and essay writing, photography, cinema and theater. During the 1960s he got in touch with the Fluxus movement and with the European neo-avant-garde, becoming friends with Robert Filliou and Wolf Vostell. During this decade and up until the 1980s, he organised courses, conferences and exhibitions on experimental film, video art, performance and happening, while promoting connections between the international neo-avant-garde and the Portuguese context. The exhibition Alternativa Zero (Galeria Nacional de Arte Moderna, Lisbon, 1977) synthesized his project of creating a Portuguese avant-garde in aesthetic and ideologic dialogue with its international counterparts. He published extensively in magazines and newspapers since the 1940s, and his critique was instrumental in encouraging experimental artistic practices in Portugal. His strong involvement in the film society movement was a major contribution towards the outbreak of the "New Cinema" announced by his only feature film, Dom Roberto (1962), awarded twice at the Cannes Festival in 1963. He was the Portuguese commissioner for the Venice Biennale in 1980, 1982 and 1984.

The Ernesto de Sousa Center for Multidisciplinary Studies (CEMES) springs from the artistic, curatorial and essay writing legacy of Ernesto de Sousa, which is fundamental for the study of Portuguese and international contemporary art. In this sense, CEMES encourages contemporary artistic research, through national and international cultural exchanges, by developing interdisciplinary and transdisciplinary collaborative artistic projects and by granting access to Ernesto de Sousa's estate in a variety of means continuously updated and interconnected.

48 artists, 48 years of freedom is the name of the artwork that will be symbolically created on 10 June 2022 in the maat Gardens, a collective mural intervention that reinterprets the work entitled Painel do Mercado do Povo [The People's Market Panel] created by the Movimento Democrático dos Artistas Plásticos [Plastic Artists for Democracy Movement] on 10 June 1974, in Belém. The reinterpretation of this mural, 24 meters long and 3 meters wide, has the participation of 48 artists: some of them participated in the creation of the original panel and the others are artists who stood out in the Portuguese art scene during the last 48 years of democracy in Portugal, an anniversary celebrated this year, and some of them are part of the exhibition Interferences: Emerging Urban Cultures (maat, 30/03–05/09/2022).