LIMA CARVALHO

48 artists, 48 years of freedom

Lima Carvalho (Porto, 1940) interviewed by Filipa Lowndes Vicente at maat on 10 June 2022,* on the day the 48 artists, 48 years of freedom mural was painted

Participation in the mural at maat, 10 June 2022

I found out last week that maat was organising the painting of a collective panel on 10 June this year, 2022, in homage to the panel created on 10 June 1974. And that they had tried to invite everyone who had taken part 48 years ago. I was taking it easy, working on engravings, when my wife called: “Hey, there’s an article in the Expresso newspaper about the panel you worked on. There are a few photos, taken today, of the group of 48 artists who are going to create the new panel, but you’re not in them. You can see Manuel Botelho, Emília Nadal…” I phoned Emília: “So, what’s going on? I worked on the panel in 1974 and was on the central committee of the Movimento Democrático de Artistas Plásticos (MDAP) [Plastic Artists’ Democratic Movement]. But I wasn’t invited to participate.” They hadn’t been able to find my number. But Emília talked to them and here I am.

The 10 June 1974 at Galeria de Belém

We were young at the time. Otherwise, we’d be dead by now. The really old ones didn’t work on it. Do you know why? We invited them, but they didn’t want to take part. They asked, “Is there any scaffolding?” We said, “Yes.” And they replied, “Then, forget it.” They were already pretty old. Hogan, Dourdil, Abel Manta, they weren’t interested. We said, “It’s very safe.” But they replied, “It doesn’t matter.” And they didn’t go. The scaffolding was three floors high with wide steps between them and a handrail. Each square of the panel was 1.5 metres across. I got one of the squares at the top. That was both good and bad. Do you know why it was good? Because the public wasn’t always looking over my shoulder. There was a big crowd… And it was hot up there. It was a really hot day. And there were spotlights too. I had one right by my side.

It was fixed for three in the afternoon, but when we arrived at the place where the canvas was, there was an impenetrable crowd. It was hard to get to the scaffolding. The panel had 48 identical squares and a draw was held to decide which one each of the 48 artists would get. These 48 squares also symbolised the 48 years of fascism. There were no arguments. We all accepted it. In some cases, the paintings beside each other were even inter-connected.

I wrote “Joana” and “João”, the names of my kids, who were five and six, on the part I painted. Others wrote political slogans. [Júlio] Pomar, for example, who was deeply in love with Graça Lobo, drew a hammer and a sickle with the letters of the name “Graça” – intertwining the symbol of the party and his wife’s name.

We were visited by individuals – politicians, personnel from the Movimento das Forças Armadas (MFA) [Armed Forces’ Movement] – who we sometimes gave brushes and paint to so that they could contribute to our paintings. There was a huge sense of community between us and those who watched or visited. There was no disagreement at all. We all shared brushes and colours. There was a bond between us. There were no second attempts. The panel was started and finished on that afternoon.

The 25 April 1974

The revolution on 25 April was sudden. We weren’t expecting it, despite the events of 16 March, when a platoon of soldiers marched on Lisbon from Caldas da Rainha but aborted the mission before reaching Lisbon, with some of the officers being put in prison. We learnt later that Otelo [Saraiva de Carvalho, one of the revolution’s leaders] told these colleagues not to worry, because they wouldn’t be in prison for long.

At the time of the revolution, art, painting and culture in Lisbon and Porto were experiencing a heyday. There was a great artistic outpouring. Some painters even had a waiting list. On 25 April, I myself had an exhibition at Galeria Ottolini in Rua António Augusto Aguiar, which is now a bakery, near El Corte Inglês. It was on the spot where there had been plans to build Lisbon Cathedral. Art at that time was booming. People were earning easy money buying and selling shares. But 25 April changed all that.

The group ACRE with Clara Menéres and Alfredo Queiroz Ribeiro

When 25 April happened, we stopped painting in the studio. We went out into the street, because that’s where everything was going on. Art couldn’t continue as a studio thing, because events were taking place outside. It was a unique moment. That summer, we decided to act. We, Clara Menéres, Alfredo Queiroz Ribeiro and myself, created a group called ACRE, and we produced public art in ‘74 and ‘75. One of the pieces we did was at the Torre dos Clérigos, in the heart of Porto. It wasn’t easy, but we never did anything just by ourselves. We always had spontaneous collaborators. To hang the yellow ribbon at Torre dos Clérigos and to paint the polka dots in Rua do Carmo in Lisbon, friends and others turned up to help.

After that, we did several other pieces. We created a government department where art diplomas were given out to whoever wanted one – people paid 20 escudos per diploma. In Lisbon, we set up a government department in a bookshop in Rua da Trindade. In Porto, we did the same thing in Galeria 2, an art gallery in Avenida da Boavista. Another of our initiatives at this time was in Caldas da Rainha, on the façade of a building. We asked someone to make a marble plaque with the words “Aqui nasceu El-Rei D. Sebastião I” [On this site was born Sebastião I, King of Portugal] on it. I asked in a café who the building belonged to and they told me the owner was a local lawyer. I went to see him and I explained what our idea was – that we already had the marble to make the plaque, that we were an art group and that we wanted to do something symbolic. He thought about it for a while and then said yes. Which is frankly amazing. I wish I could remember his name. We mounted the plaque on a summer’s evening. The next day, I went to see it and I overheard a group of people saying, “I didn’t know Sebastião I was born here!”

In ‘75, our companion Queiroz Ribeiro died in a car accident. Clara Menéres was superstitious and considered calling it a day, but she changed her mind, and we did a few other projects.

The meetings of the Movimento Democrático de Artistas Plásticos

I was a member of the MDAP [Plastic Artists’ Democratic Movement]. We would meet at various places, such as Tempo, an art gallery near the Sociedade Nacional de Belas-Artes (SNBA) [Portuguese Fine Arts Society]. We spent a lot of time at the SNBA, but either before or later, I can’t recall precisely, we moved to Gallery 111 in Campo Grande… We were drawn to Manuel de Brito because his gallery had space, we could do what we wanted and during the meetings he’d give us a glass of port or a brandy… And we met there several times. We had a few ideas. One was the panel. But there were occasional differences of opinions and things would grind to a halt. But the ones we did do were the statue covering, the panel and a few posters.

Some of the posters were done by [Marcelino] Vespeira and others by João Abel Manta. We wouldn’t print them, because we didn’t have the means to do it. We – the artists of the MDAP – did the drawings and then handed them to the army, the MFA, and they paid for the printing. The posters appeared bit by bit – some on the initiative of the artists themselves, others suggested by friends of artists who encouraged us to make the posters. Vieira da Silva, for example, was one of the people invited. And he did that poster that became really well-known.

May 1974: “A arte fascista faz mal à vista” [Fascist art is bad for your eyes]

I’d read in the newspaper a few days earlier that the railways were offering free transport of statues to a place where they would be melted into plaques and inscribed with the words “Viva o 25 de Abril” [Long Live the 25 April]. It was the beginning of May. Because of that news, we went to the Palácio Foz: me, Moniz Pereira, Nikias, Sá Nogueira, Abel Manta and Júlio Pomar. We got there and asked: “Who’s in charge?” It was a captain who’d been put in charge of cultural matters. And we said: “Dear Officer …” – I think it was Captain Nunes… – “Do you not know who we are? We are very ‘important’ people within the art world. Please listen to what we are about to say. We are going to leave this document with you. It says, ‘Please do not allow anyone to destroy any of the statues.’ Because history repeats itself; it is always the same. ‘If you do not like the statues, cover them, move them somewhere else, but do not melt them down.’” I was a young man… about 30 or so. The oldest members of our group were Moniz Pereira and João Abel Manta. When we entered the courtyard of Palácio Foz some weeks later, on 28 May, us and a few others, we took a huge black sheet with us. The employees didn’t like it, but they didn’t approach us or stop us from entering. They were standing at the windows and on the balconies. Vespeira, who was very temperamental and excitable, did something that impressed me. He approached the bust of António Ferro, picked up a plastic bag and put it over Ferro’s head. We used Sá Nogueira, who was very tall, as a ladder. We stood on his shoulders to place the sheet and rope around the statue of Salazar.

It was really hot on both the 25 April and the 1 May. It was just politics on the 1 May. No art. We were all surprised by the crowd, marching up Avenida Almirante Reis to the Inatel stadium. There were people in the street giving the demonstrators glasses and mugs of water. Do you know why? Because everything was closed in the city. Not a single café, snack bar or restaurant was open. At the time, I was living between Lisbon and Porto. And when I was in Lisbon teaching during the week, I used to stay at the Hotel Americano in Rua 1.º de Dezembro. That day, not even the beds were made. Everything just came to a standstill...

* This interview was continued on 24 March and 21 April 2023.

|

For the panel 48 artists, 48 years of freedom I was given a space like everyone else’s that was rectangular in shape and suggestively vertical in size and positioning. It is located right at the bottom of the lowest row and on the right if you’re looking from the front. With an idea of what I already wanted to do, I started by sketching the outline of a slightly inclined female figure suggesting an upward movement in the lower section of the rectangle. I only drew the head and the upper part of the body, down to the top of the shoulder, leaving a large area free that I covered with sky blue in a vertical sense. I also tried to make this face-head look upwards, with the hair fluttering in the wind, transfigured into the feathers of a bird, like a big wing.

|

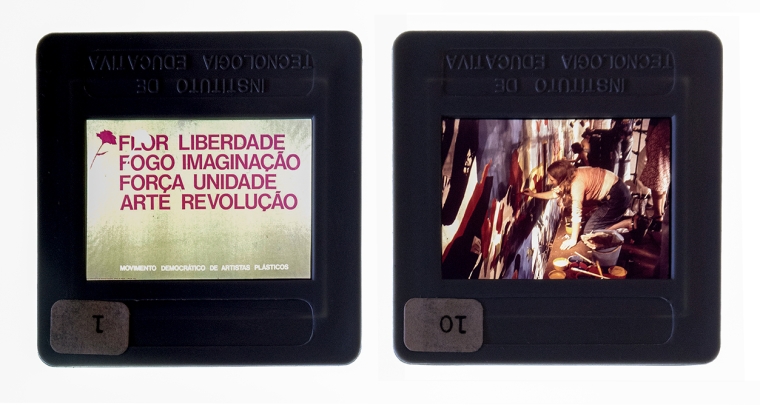

48 artists, 48 years of freedom is the name of the artwork that will be symbolically created on 10 June 2022 in the maat Gardens, a collective mural intervention that reinterprets the work entitled Painel do Mercado do Povo [The People's Market Panel] created by the Movimento Democrático dos Artistas Plásticos [Plastic Artists for Democracy Movement] on 10 June 1974, in Belém. The reinterpretation of this mural, 24 meters long and 3 meters wide, has the participation of 48 artists: some of them participated in the creation of the original panel and the others are artists who stood out in the Portuguese art scene during the last 48 years of democracy in Portugal, an anniversary celebrated this year, and some of them are part of the exhibition Interferences: Emerging Urban Cultures (maat, 30/03–05/09/2022).

|

Lima Carvalho at maat, during the painting of the mural 48 artists, 48 years of freedom, 10 June 2022. Photos: Joana Linda.