An interview with the writer, artist and editor, Robert Horvitz, speaking about his early years as a writer for Artforum and his friendship with Alan Sonfist, his disagreement with Jack Burnham about separating nature from culture, and his fourteen years (1977–1991) as arts editor for Whole Earth magazines.

ECHOING THE GROUNDWORKS TIMELINE AND THE VISUAL NATURES MAPPING: 1968

Al Perrin (Alwyn T. Perrin) organising a page of the Whole Earth Epilog, 1974. Photograph by Stewart Brand, courtesy of Robert Horvitz (also in the cover).

maat / Maria Kruglyak

You wrote extensively for the Whole Earth publications Whole Earth Catalog and CoEvolution Quarterly as well as for Artforum, but I’m curious about how it all started. I understand that Jack Burnham was a big inspiration. How did you two meet and what was it that made you start writing?

Robert Horvitz

In school I didn't think I was a particularly good writer, nor did I enjoy it, so I hadn't thought about writing as a career. But I met Alan Sonfist at the Akron Art Institute in 1972. I had a drawing show there, which was followed by a show of Alan's; so our visits to Akron overlapped. I liked his work and knowing that he was a city boy who loved nature, I invited him and his girlfriend to share a house with me in a beautiful forest in Massachusetts that summer. I had promised to take care of the house so the owner could go on holiday. We got to know one another that way and at some point Alan asked if I would write about his work and I said yes.

To make Artforum think I had something more to offer, I decided to submit an interview with George Kubler at the same time. Kubler had written a book called The Shape of Time, which was really popular among art historians and intellectuals. I knew him through Yale. In fact, we ate lunch together regularly because he was affiliated with my residential college and got free meals there. At some point I asked him if I could record some of our lunch conversations with the idea of splicing together the interesting parts as an interview and he agreed. So I finished the Sonfist article and edited the Kubler interview and mailed them together to Artforum in the spring of 1973.

When both articles were published, I sent copies to Jack Burnham to introduce myself and ask if he had anything to say about them, because both touched his interests and we had a mutual friend in Donald Burgy. Jack had written an essay for the catalogue of an exhibition Burgy had at the Addison Gallery of American Art in 1970. I met Burgy just before that show [Art Ideas for the Year 4000] and we've been best friends ever since. Jack sent back a really gracious note, saying, among other things, that he wished he had written the Sonfist article, not because he liked Alan's work, but he liked my argument against the nature/culture dichotomy. We continued writing to each other until about 1980.

maat

That is a great way to meet, and an impressive argument too. How would you say that you understood the relationship of nature and culture? How do you understand it now? And how did Jack Burnham understand it?

Robert Horvitz

It's unfortunate that Jack isn't around to answer for himself, but he wrote on this subject extensively in The Structure of Art. However, his thinking evolved significantly after that. It'll take a while to summarise, so bear with me while I quote him:

"The fundamental dichotomy expressed in mythic forms is that of Nature and Culture. Culture represents all categories created through or by man: family or tribal members, domestic animals, and artifacts. Entities falling outside the control and domain of man belong to nature... Culture is the conceptual means for distinguishing man from nature... In art, on the other hand, any entity, natural or cultural, can be naturalized for use as subject... Undoubtedly conscious knowledge of the rules of art would dispel the illusion of art at once, since these deal with unconscious mechanisms concerning the use of objects, materials, and concepts in mediating reality, namely, in defining the artist's relationships to nature and culture... [Art’s] efficacy is in conjoining permissible cultural and natural phenomena through the agency of the artist..."

So the artist conjoins and balances but does not resolve the nature/culture dichotomy. That's based on Claude Levi-Strauss' ideas, which Jack turned to in response to criticisms of Beyond Modern Sculpture [BMS]. On the first page of The Structure of Art he wrote:

"Much of the impetus behind The Structure of Art results from my own as well as others critical examination of my first book, Beyond Modern Sculpture. By last year the internal inconsistencies of that book were very much on my mind. And just as vexing is the fact that I believe that many of its theories remain creditable. Its historical presumptions impelled me to study the writing of Claude Levi-Strauss with more than casual interest...”

“[BMS] defines chronological parallels between science and art as responsible for shifts in visual expression. Chronologically there are some strong correspondences between artistic and scientific innovation, but these are coincidental not causal relationships." (2nd ed., p. 24)

Really, Jack? If you read BMS, you know that it argued for something a lot stronger than coincidental correspondences and chronological parallels. Jack's critics accused him of technological determinism. He seemed to accept that criticism and embraced structuralism instead.

As far as I'm concerned, he was led astray by Levi-Strauss' idea that nature and culture is "the fundamental dichotomy" and he followed that into a rabbit hole of increasingly tenuous refinements. "Nature as Artifact: Alan Sonfist" interested him because I rejected that dichotomy. I see humanity and all cultural expressions as part of nature. And I can say from our correspondence that Jack realized one should not – cannot! – separate nature and culture. But in terms of his intellectual re-positioning, that realisation came too late. The revised edition of Structure of Art came out in June 1973 and my Sonfist article was published in November 1973. But he never outgrew his interest in structuralism, and in fact, he pushed deeper into even more esoteric non-causal systems of explanation, like Kabbalah.

The reason wasn't clear until much later, and here I must paraphrase because he never gave a full written account of his mystical turn. But the gist of it was that he realised the part of art history that you can explain as a rational response to the impact of technology is less important than the part that you cannot explain that way. Artists like Marcel Duchamp and Joseph Beuys have outsize impact precisely because their work cannot be explained by technology’s influence; there’s a lot more there. Jack told Lutz Dammbeck in 2002 that "art works not from what you see and what can be said about it but what you see and you don't understand." That puts critics and historians in a difficult position, because the only way to talk about such work is with explanations that evade understanding. And that's what Jack started producing after The Structure of Art, and fewer and fewer places wanted to publish such articles.

I see humanity and all cultural expressions as part of nature.

maat

Returning to Alan Sonfist, what is your understanding of his Time Landscape within this dichotomy of nature and culture?

Robert Horvitz

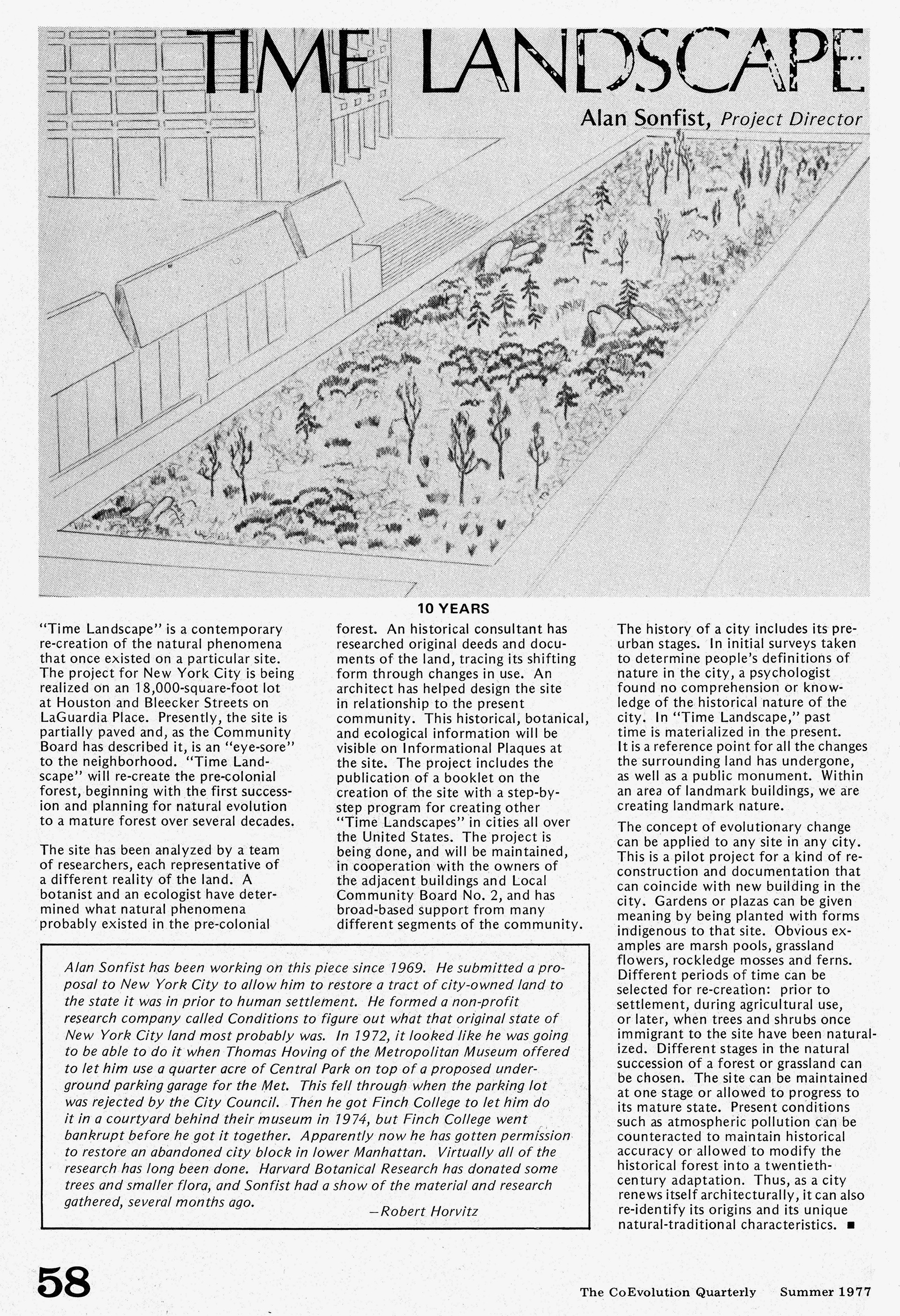

Time Landscape combines plants native to Manhattan which co-evolved long before humans became the dominant influence, so it shouldn't surprise anyone that they thrived when re-assembled. The first time I saw it, a few months after the initial planting, it was already clear that it was going to look very different from an abandoned lot; it had a vitality that was greater than the sum of the parts. It certainly made Alan’s point that such references are needed to show us what our environment was and what it might be like without us. It also showed “re-wilding” can work even in a city centre.

Let me come at this from a different angle. Alan was sensitive about his work's similarity to Hans Haacke's. But I always saw them as different. Hans was exploring systems, and he realised very quickly that the concept of a system is a bridge between nature and culture. He crossed that bridge very early to explore social and political systems. Alan worked with systems too and crossed the same bridge occasionally. But he was motivated by a love of nature which one didn't feel in Haacke's work, which was rather more, can I say, systematic. Some people found Alan's work more naive because of that difference – its "tree hugger" aspect. I saw that as simply an honest difference between them and over time I think Alan's love of nature has been recognised as something that gives his work meaning. I'm sorry I didn't bring that out more in my article. Instead, I over-intellectualised his work for my own purposes, mainly to challenge Jack Burnham.

maat

Turning to your many years of involvement with Whole Earth, how did that begin?

Robert Horvitz

After that summer with Alan, I lived with a woman who was a big fan of the Whole Earth Catalog and when they announced that they were going to start a magazine, she subscribed. I started reading CoEvolution Quarterly from the first issue, too, and I saw it getting better and better. But it had one very odd weakness: their coverage of the arts was poor-to-non-existent. So I wrote to Stewart Brand about that, and cited earthworks as an important development in sculpture that his readers should know about. I sent him a sketch of Time Landscape that Alan had made for his proposal to the City of New York; photos of a work by Charles Ross; a photo of one of my drawings; and texts by Donald Burgy and Henry Flynt. About a month later I got a postcard from Stewart. It said they loved everything I sent. They'll publish everything but spread over the coming year. Keep sending us stuff and how about if we list you on our masthead as art editor? I sent a postcard back saying “Great, great and GREAT!!”. And that was the beginning of a fourteen-year relationship, which lasted until I moved to Prague in 1991 and saw that I wouldn't have as much time for gathering and preparing material for them as I had in the 1980s.

During that time I was art editor of CoEvolution and the Whole Earth Review. I only contributed reviews to the Catalogs. But I also hosted the Whole Earth conference on the WELL, which was the online community we started in 1985. In any issue of the magazines I had 2-4 pages to present artwork, and then I started writing about the radio spectrum and electronic communication. So after a while my title on the masthead changed from "art editor" to "Washington correspondent" and then to "contributing editor."

maat

What was your experience working with Stewart Brand?

Robert Horvitz

Stewart was already starting to phase himself out of Whole Earth around the time that I came onboard, though that wasn't clear until the 1980s when he really wasn't involved at all. He wanted to focus on his Global Business Network, which aimed at changing the thinking and behaviour of large corporations. When he was still Whole Earth’s publisher and editor, we hardly ever spoke, so I felt that I had complete autonomy in selecting work for the magazines.

You have to understand that I didn't live in the San Francisco area. I lived on the east coast, so my relationship with Whole Earth was by phone, mail and, after the mid-1980s, text conferencing through the WELL. I did visit the office a few times to meet people in person, and participated in some events they organised. Stewart and I discussed very early on whether I should move to California, but he felt I would be more useful staying on the east coast because it gave me access to different people and projects and I could run errands that would have been inconvenient or costly to get someone from California to do. I worked much more closely with Stewart's successors than with him, especially with Kevin Kelly. Kevin and I spoke almost every week to brainstorm ideas for the magazine.

maat

You mentioned in our earlier conversation how one edition of the Catalog was created in a campervan as an experiment, but that this was not how it was usually produced. What was the process otherwise and could you tell that particular story?

Robert Horvitz

The Whole Earth Catalogs were pasted up the old fashion way: by hand, with beeswax or rubber cement spread on the back of small strips of paper and typeset words on the front. Our typesetter was an IBM Selectric typewriter, because it had variable spacing and a variety of fonts.

This first photo shows the Catalog production in 1971. Stewart’s on the left, talking on the phone:

The Whole Earth Catalog production, 1971. Unknown photographer, courtesy of Robert Horvitz.

Stewart lines up a block of text:

Stewart Brand pasting up the Whole Earth Catalog, 1968. Unknown photographer, courtesy of Robert Horvitz.

Creating each catalogue’s page was like solving a jigsaw puzzle, except there is no unique solution. Here is Al Perrin trying to organise a page in the Whole Earth Epilog (1974):

Al Perrin (Alwyn T. Perrin) organising a page of the Whole Earth Epilog, 1974. Photograph by Stewart Brand, courtesy of Robert Horvitz.

Office manager Andrea Sharp used a card file system to keep track of all the products (candidate and chosen) for review. What you don’t see are the plastic bins used to sort and store the products themselves, which filled a small warehouse:

Office manager Andrea Sharp with her card filing system, 1974. Photograph by Stewart Brand, courtesy of Robert Horvitz.

In 1971 Stewart had the crazy idea to produce the Last Catalog in a desert seventy miles from the nearest telephone and with no access to electricity, just to show it could be done. They brought a geodesic dome in pieces to assemble there…

Geodesic dome assembled next to production location for the Last Whole Earth Catalog, 1971. Photograph by Stewart Brand, courtesy of Robert Horvitz.

…and a large inflatable building…

Inflatable building brought to production location for the Last World Earth Catalog, 1971. Photograph by Stewart Brand, courtesy of Robert Horvitz.

But the wind was so strong that it promptly blew these structures away and production had to move into the small AirStream campervan that Stewart and his wife Lois used to transport supplies to the site. Only two people could fit in the van at the same time, which slowed the work so much that the idea had to be abandoned.

maat

Fascinating. Could you also share some images of the pages you created for the magazines with us?

Robert Horvitz

Here’s one you’re familiar with already. This is the first presentation of Time Landscape in print, from 1977:

Time Landscape by Alan Sonfist in The CoEvolution Quarterly, 14 (Summer 1977) introduced by Robert Horvitz. Courtesy of Robert Horvitz.

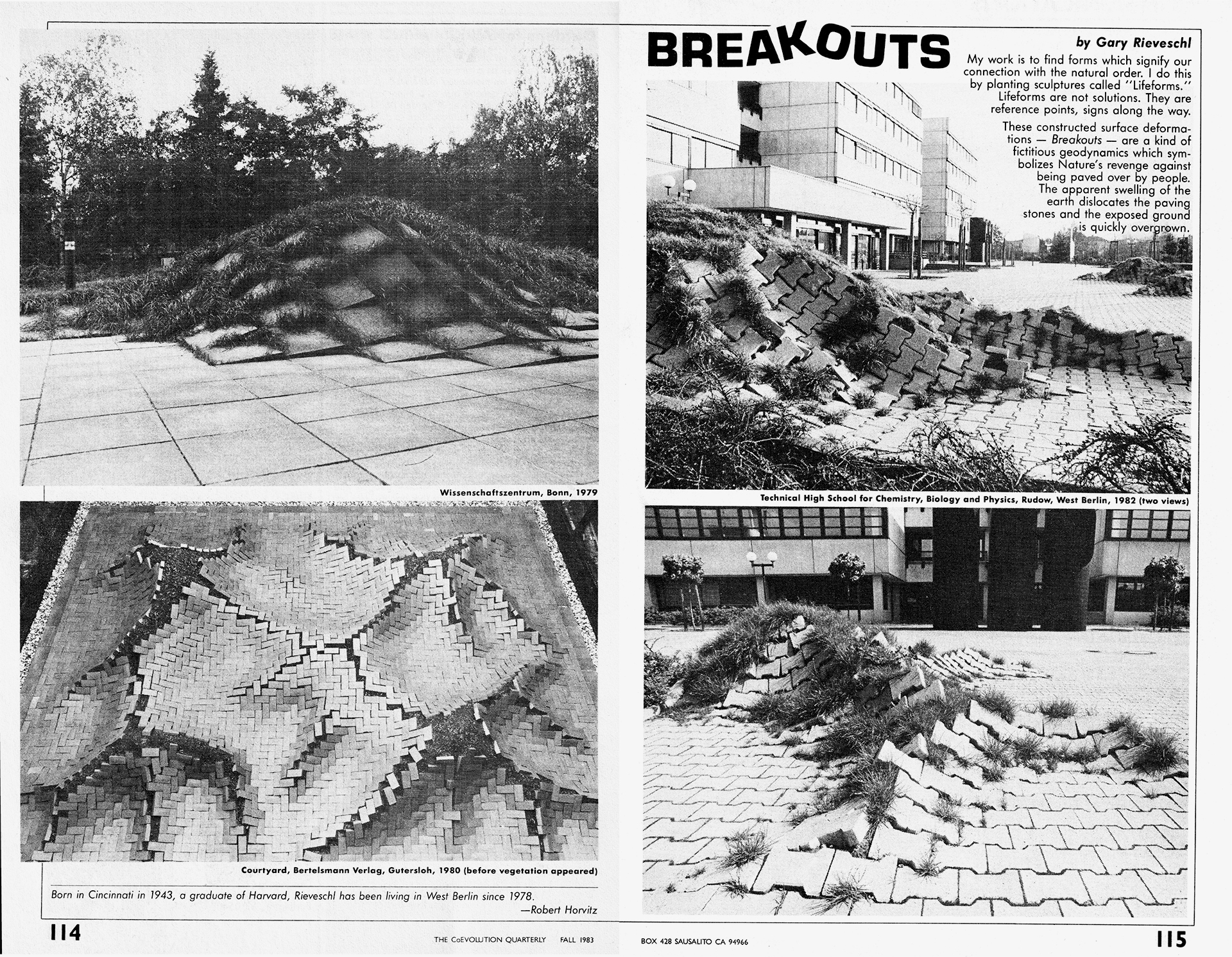

Here are a few pieces by Gary Rieveschl, an American who was living in West Berlin:

Gary Rieveschl’s Breakouts in The CoEvolution Quarterly (1983) introduced by Robert Horvitz. Courtesy of Robert Horvitz.

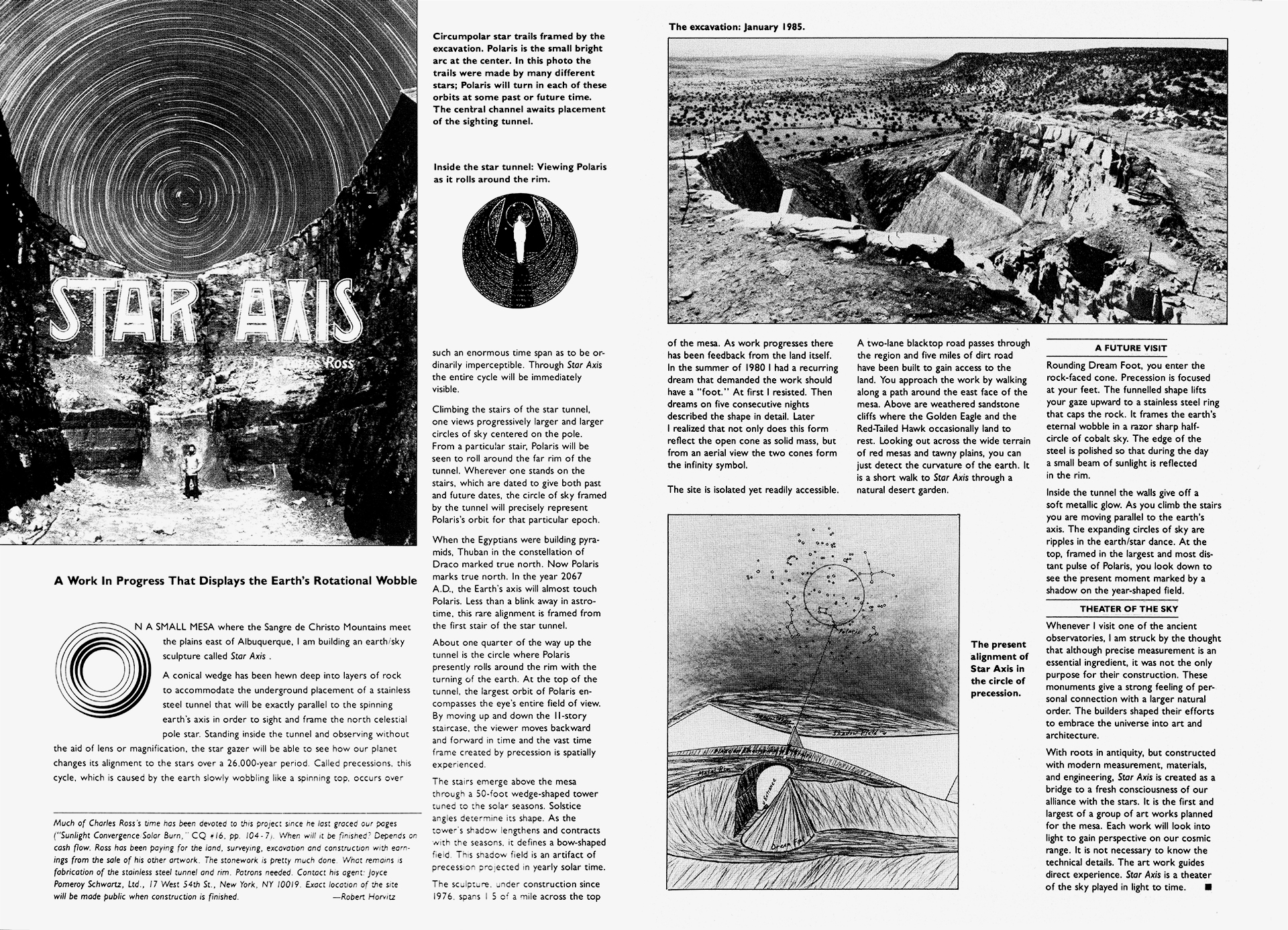

Charles Ross’ work was featured in both CoEvolution and the Whole Earth Review. This is the second layout, from 1985. Ross has been working on Star Axis for about forty years. He hopes to finish it in 2025:

It’s not an art layout, but here’s a short piece I wrote for the 20th anniversary issue of the Whole Earth Review (1988) which is relevant to maat’s survey of environmental sculpture [Visual Natures]. Kevin Kelly asked regular contributors and staffers what they were working on and this is what I sent:

Courtesy of Robert Horvitz.

maat

Going back to Stewart Brand moving away from the Whole Earth Catalog already in the 1980s, that was not something I had heard of. You also went on to work with a different cast of characters if I understand correctly?

Robert Horvitz

When Stewart started publishing the Whole Earth Catalog he said he would only do it for 5 years, and he really did try to end with the Last Whole Earth Catalog in 1971. But public demand was insatiable and he went on to publish the Whole Earth Epilog, the Whole Earth Ecolog, the Electronic Whole Earth Catalog, the Whole Earth Software Catalog, the Next Whole Earth Catalog, the Essential Whole Earth Catalog and quarterly supplements. This was an increasingly repetitive burden, so in the early 80s he wanted out. But his exit was so gradual that many of us believed it would never be complete. Eventually it was. He just slowly shifted responsibility to others that he thought were ready to operate without his judgment as a safety net. Kevin Kelly’s coming in as CoEvolution’s editor made a big difference. Kevin seemed to restore the energy of Whole Earth’s early years without repeating what Stewart had done. So Stewart just got out of his way.

My post-Whole Earth transition was also pretty smooth. In 1989 I was putting together a 40-page section for the magazine called Radio Earth. It was about living in an electromagnetic environment. We’re normally not aware of it but the Earth has a huge permanent electrical charge, some of which manifests as lightning. The section had other topics too, like radio astronomy, deregulation of broadcasting, the health effects of radio exposure, etc. A TV journalist called while I was putting this together to ask if we would be interested in an article about pirate television in Eastern Europe. This was right around the time of the anti-communist uprisings, so I said yes definitely. The journalist was Evelyn Messinger, one of the founders of Internews. Internews had pioneered the use of live interactive satellite TV programmes as a way to improve relations between hostile countries. They organised discussions between members of Congress and the Soviet Politburo, between Israelis and Palestinians, between religious leaders in Iran and the US. Brilliant, daring, big-league stuff. Internews wanted to get involved in the changes happening in eastern Europe and when we finished editing her article, Evelyn asked if I would join them. They had won a contract from the US government to write a report on what it would take to de-monopolize broadcasting in post-communist societies. I agreed to co-author that report and create a manual for people with no technical training about how to build and operate low-power radio stations. The Local Radio Handbook, as it was called, was a real hit. It was translated into six languages and went through multiple printings.

Evelyn then introduced me to the editor of the New York Times’ Sunday magazine, who wanted to create the Center for Independent Journalism in Prague. This would offer training and facilities for new Czech journalists and visiting foreign reporters. I was picked to be the Center’s “director of radio activities” and moved to Prague in 1991. A few months later, George Soros hired Internews to develop a programme of support for journalism in the countries where he was creating foundations. Evelyn and I ran that programme: she handled television, I did radio, and together we started TransNews, a daily satellite video newsclip exchange for TV stations in eastern Europe. By 1995 our work was less about starting new stations and more about helping existing stations share programmes, lessons learned and how-to information. That led very naturally to expanding internet access throughout the region.

The challenge we faced was: are there enough readers interested in both practical tools and advanced concepts – a combination essential to Whole Earth’s appeal – to sustain the production of first-class magazines which carry no advertising?

maat

Fantastic. You mentioned at one point that when you moved to Europe and started this new line of work, your perspective on Whole Earth changed. What caused that shift after fourteen years?

Robert Horvitz

Almost everyone on the staff believed the Whole Earth Catalog was a big step toward planetary culture, and we really did make an effort to include resources and ideas from outside the US. But the reality was that everything we published was in English and nearly all the publications we reviewed were in English, too. That bias was more obvious when viewed from eastern Europe, where Russian and German were more common second languages than English.

David Marx just had an interesting thread on Twitter about the Whole Earth Catalog’s impact on Japanese fashion magazines, which apparently was huge even though they had no idea what the Catalog was about. They didn’t get the philosophy behind the Catalog, its content or purpose, because of the language barrier. They just liked the style of presentation. So clearly language differences limited development of a truly global culture and that’s something we couldn’t overcome. Conditions have really improved since then, with the spread of the internet, online publishing and Google Translate. But magazine publishing on paper hasn’t benefited from these changes. Quite the opposite.

The challenge we faced was: are there enough readers interested in both practical tools and advanced concepts – a combination essential to Whole Earth’s appeal – to sustain the production of first-class magazines which carry no advertising? That formula worked for 20 years, but eventually costs and competition rose, and we were no longer able to break even. Eventually we couldn’t even pay the printer, let alone the staff, so publication had to stop. The last issue appeared in 2002 as a PDF file and that was the end.

Still, it was clear from the vantage point of Prague that Whole Earth Catalog was an inspired team effort, thanks mainly to Stewart Brand’s farsightedness, with great diverse input from a whole lot of other people. That doesn’t happen often enough, so I’m extremely glad to have been part of it.

Robert Horvitz studied art at Yale, graduating in 1969, and went on to teach drawing and contemporary art at Yale, MIT, Rhode Island School of Design and now Anglo-American University in Prague. After writing feature articles for Artforum, he joined Whole Earth in 1977 as art editor of their magazines before moving to Prague in 1991. He has exhibited his drawings at the Museum of Modern Art and the Clocktower in New York, the Institute of Contemporary Art in Boston, the Akron Art Institute and elsewhere. In Prague, Horvitz mainly worked on the reform and development of electronic media and the expansion of internet access. He is currently working on a study of the future of television and teaching drawing.

Visual Natures (maat, 30/03–05/09/2022) is the product of more than two years of critical investigations around climate science, creative practices and eco-politics. A continuation of the data-driven installation Earth Bits – Sensing the Planetary and the public programme Climate Emergency > Emergence, both conceived and ignited by Beatrice Leanza during her directorship of the museum, the project surveys political, social and cultural forms of collective agency from the 1950s onwards that demonstrate how our understanding of “nature” informs the ways in which we organise, sustain and govern our communities as an expanding planetary construct, in concept and in practice.

On maat ext., the series #groundworks introduce the critical explorations that feed into the complex interconnectivity between the environmental and energetic quests and its reverberation through decades of artistic creation and cultural dynamics, traced from the 1950s until today, and continues these investigations through collaborations with artists, curators, archivists, researchers and activists on their work and the meanings of ecology, environmentalism and societal responsibilities in the face of climate change.

Explorations is a programme framework (maat, 2020–2022) featuring a series of exhibitions, public and educational projects delving into the multi-faceted subject of environmental transformation from various scholarly and experimental vantage points – it brings philosophical and political perspectives forward, as well as sociocultural and technological investigations interwoven in speculative and critical practices in the arts and design at large. Central to this discursive and critical effort was the establishment of the maat Climate Collective in 2021, chaired by T. J. Demos, and geared toward assembling diverse cultural practitioners working at the intersection of experimental arts and political ecology.