Echoing the Groundworks timeline and the Visual Natures mapping: 1965–1973

Drop City is considered the first rural hippie commune and was very influential although it only lasted for 8 years. It started in 1965 as one filmmaker and three art students bought a 7-acre plot of land to live and work in together. Avoiding hierarchies, Drop City stood for the post-Vietnam War growing desire to "drop out" of consumerism, individualism and the US way of organisation. Two of its founders, Gene Bernofsky and Richard Kallweit, shared some of their memories of what Bernofsky calls “an UNintentional non-community of a few youthful rebel fools striving to avoid the macabre military draft of the Vietnam war imposed upon the youth by the warmongering United States Government”.

Communication with them was established through Tim Miller, the author of The 60s Communes: Hippies and Beyond (Syracuse University Press, 1999). Acknowledging Drop City’s fit into Visual Natures, he happily forwarded our inquiry to get in touch with some of the founders and a few other people who lived there that he is closest to, with a warning: “Some of them are sceptical of projects like this, but it is hard to predict just how they will respond. … If they decide to work with you further, they can contact you directly.”

As it turned out, Richard Kallweit and Gene Bernofsky were more than happy to share photographs and miscellaneous writing, including a piece from a memoir-in-progress and forwarded email correspondences – as well as a book recommendation: Droppers: America’s First Hippie Commune by Mark Matthews (University of Oklahoma Press, 2010).

— Maria Kruglyak

All images, unless noted otherwise: Drop City, 1966. Courtesy of Gene Bernofsky.

|

|

From Richard Kallweit on 15 December 2022. A piece that, he admitted, is part of a booklet in progress.

Richard’s Dream

I saw recently a movie Christiana about a commune in the center of Copenhagen that has been going on for forty years. It started as squatters on an empty army base. I began to think of Drop City as lasting fifty years as an actual place than as a virtual place. And, anyhow, is an actual place more real than a virtual place, as in a book, movie, poem and so on? A few reminiscences. People are always saying that I was at Drop City the longest. But actually, I was there a shorter period of time, out a lot in Colorado, New Mexico and New York. I will talk about some of these adventures later.

A lot of people would come to Drop City and say they were someone else: who was to know?

One of the main facts about Drop City is that we were really really young, only in our twenties. One of the funny things that always happens is that stories are important. But oftentimes they become appropriated by someone else so that years later I might be sitting in Charlie’s studio in New York and he would be telling me about the day he spent with the “child actor” Brandon DeWilde. I would look at Charlie [DiJulio] and say, “Charlie, that was me.” And he would say, “Not anymore”, and laugh in his usual way. A lot of the stories would center around “famous people”. Who wants a story about an ordinary person? Well, for one, I do! So much more interesting! Also, a lot of people would come to Drop City and say they were someone else: who was to know? I remember Mike recounting a whole musical night with Jim Morrison. I said “Are you sure?” and he said “I think it was him, there was a crazy dude who really knew music”. Here’s the classic gap of logic and words failing to meet memory, dreams and expectations.

Here are two of the well-known ones. There were Billy Hitchcock and Tim Leary. They flew into Trinidad and came out to Drop City. There’d been a huge drought for about two months before they showed up and, when they did, we had a monsoon. So all the droppers went around saying, “Tim, you brought the rain, Tim, you brought the rain”. Of course, he got irritated, not wanting to walk around as kind of a hero. Our youth showed. Another time, we were sitting in one of the domes with Tim and his friend, passing a joint around. I was sitting next to Leary and when the joint got to me I was so stoned I’d send it back the other direction. So, it never got to him. Finally, somebody lit up a new joint and handed it directly to him.

Before we decided to build domes, we had an idea of just building A-frames. We were all up at University of Colorado in Boulder which had a conference on World Affairs and [Buckminster] Fuller was one of the main speakers. In the lecture hall, where he was going to speak, we put up a banner that said “The Droppers endorse Bucky Fuller”. Which was funny, because we were nobody at the time, and he was somebody.

Here’s an example of how things happen. A postcard from NYC comes in the mail, with the greeting “Hello, my name is Jalal and I’m an artist, looking for a place to live with my five-year-old son,” I write back, “Sure, you can come out.” I don’t know how the logistics worked out; maybe we had a telephone at that time. How she got there is her story. She became a permanent resident and, as it turned out, my wife. She was in for a shock. She expected a retreat, a kind of a Yaddo but, as Clark [Richert] said, “it wasn’t like that. It was rice and beans.”

In many of the photographs I’ve seen of early communes, there’s a picture of about ten guys and four women. Happily, that would change as Drop City evolved. One pattern though that seems universal is that some people stayed for years, others for days or weeks, and in between, the process of assimilation of people into the community which in itself is interesting, the movement from the margins to within, like later when I lived with my family in a car in Placitas New Mexico and over months moved into a home.

I wistfully looked back on those times as we all do on our strong experiences of youth before our long thirty-year jobs of sustaining ourselves into maturity and see how so much of what we were thinking about is mainstream: scrounging, domes, acceptance of soft drugs, connecting to the land, revitalizing areas forgotten like the seven acres we first built domes on, revitalizing the arts.

I wistfully looked back on those times as we all do on our strong experiences of youth (...) and see how so much of what we were thinking about is mainstream...

|

|

On 31 December 2021, Gene Bernofsky forwarded a correspondence between himself and Elizabeth DiJulio, the daughter of Charles DiJulio, who lived at Drop City as a little girl. Her father was a close friend of Gene’s and also a co-founder of the commune, Elizabeth asked Gene: how come all the write-ups on Drop City never mention Charlie’s name as a co-founder or even a participant?

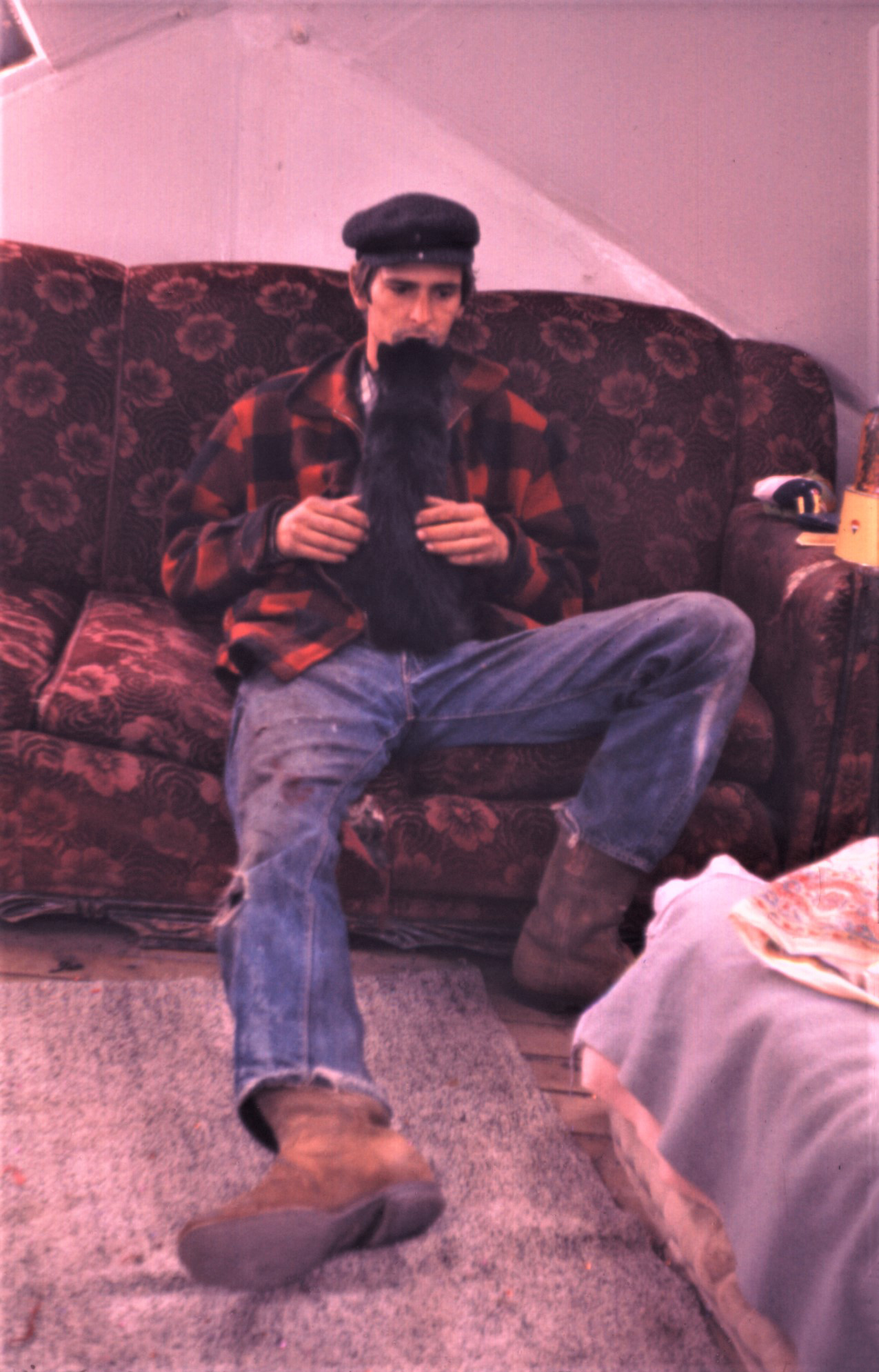

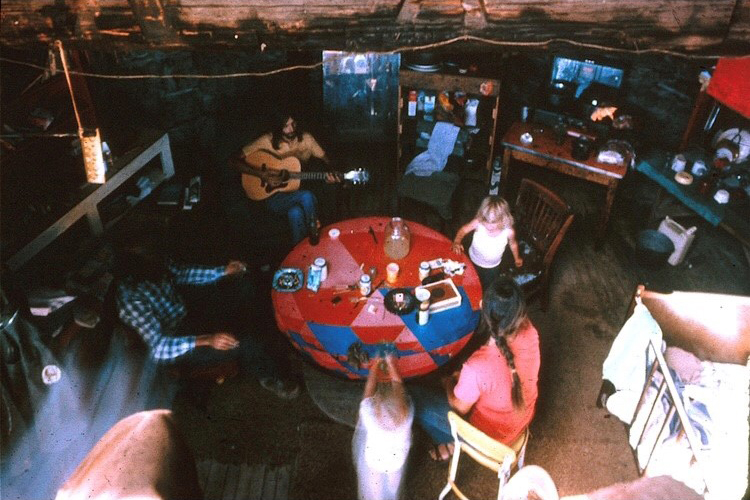

Charlie DiJulio with his cat in his dome in Drop City, 1966. Courtesy: Gene Bernofsky.

First off, all of us were financially destitute...from beginning to end. Jo [JoAnn Bernofsky] and me [Gene Bernofsky] and Clark [Richert], just the three of us, showed upon the DC land in May of 1965. We lived in our car and a neighbour's barn until we got our first dwelling halfway up. That first year we put up that first dome, the kitchen dome and the big dome structure. About halfway through that Richard Kallweit, a friend of Clark’s, showed up.

Elizabeth, it wasn't until June of 1966 that your family moved from Boulder onto the land. That was over a year since the so-called founding. [Peter] Douthit, an old friend of Charlie's, showed up soon after your family came. Now Douthit and Clark were both very self-promoting. Me and Charlie were not. We wanted only a quiet place where we could simply make things without a lot of distraction and noise. Clark and Douthit wanted recognition and to become famous. That self-promotion led to the Joy Festival of June 1967.

Charlie and I were pretty upset and disappointed that DC [Drop City] had taken the route of self-promotion and recognition. My family and your family left DC after the first insane night of the "joy festival”. It was heartbreaking for me to leave. The original vision I had for DC was totally upended by the self-promoters. I tried and failed to stop all that noise. Douthit was the main instigator of the drive for fame and Clark followed along. Your dad was a gifted and talented artist. He hated the self-promotion bullshit, as did I. It ruined DC.

Consider all the negative activity after our families left. The killings, the suicides, the fights etc. Elizabeth, I never knew about all that awful stuff until I saw Joan Grossman's film. I know it's a good film. Joan is my friend. But I can't stand watching the second half of her film. Through it all Charlie and I became close friends. He welcomed me and Jo and May onto your land at Thorn Lake. No questions asked.

Jo and I came to love your family. You're right about those bonds still strong. I have loving memories of you and Christina and Carol and Bella! It was your family that founded the real dropcity [sic] on your beautiful land. I wasn't strong enough to fight off the self-promoters in DC. But with the help from your family, Jo and I were able to put it all behind us and make a fairly good life. Though we really never accomplished much financially, I don't regret that and I'm not bitter about it. It was your dad who turned me on to filmmaking. Charlie gave me his 16mm camera and I never looked back. Wound up making over forty films.

Richard Kallweit on 12 January 2022.

We really did not have rules as such. Maybe some unwritten ones and the rule of no rules. I think one of the reasons DC was to keep on being sort of interesting is that it initially was to be an artwork.

|

|

Mark Matthews Droppers: America’s First Hippie Commune is based on two years of interviews with Gene Bernofsky as well as several other Drop City artists, but also short stream-of-consciousness paragraphs of historical context pieced together from newspaper articles, novels, and biographies month per month as well as longer contextual texts. Introducing the book to me, Gene wrote: “At first I told him I would not be interviewed unless he wrote the book in the context of the Vietnam War. He agreed to that stipulation and in consequence he did a brilliant job.”

Before the founding of Drop City, Clark Richert and Gene Bernofsky met at the University of Kansas, where both Richert and Bernofsky’s wife studied. In 1962, Clark invited Bernofsky to move in with him in his loft.

“Clark [Richert] and I [Gene Bernofsky] defined our art as ‘droppings’. We weren’t artists, we were ‘droppers’. A lot of times we would tie a rope to stuff and drop it down to the street and sit up there and watch the reactions of passers-by. We thought we had invented a whole new approach to making things. It was a way to cope with the disgusting elitism of art. Our pieces were just droppings, others called them collages. It was funny.

Once we set up an ironing board with an iron and a shirt on the street and then stuck the plug into the slots of a parking meter. People would come by, and some would stop, and try to iron the shirt, and laugh, and have a good time. Another time we cooked up a breakfast of bacon, eggs, toast, juice, and coffee, and set it out on the sidewalk in front of the hotel across the street from us. No one removed it all day long – not even the hotel people. People would walk up to it and look to see what was going on. Finally, someone rode their bicycle right through it and smashed it. Later that day we went and cleaned it up.” (p. 40)

In 1942, Gene Bernofsky moved out of town and bought a farm to grow marijuana – which turned out to be hemp – and then came to New York to sell it. A brief and unfortunate stint in North Africa and Europe later, the Bernofskys came back and together with Clark Richert began the adventure of Drop City.

During the remainder of the spring of 1965, Bernofsky sold his few remaining bags of marijuana. “A few weeks later”, he said, “we decided to get into our car and drive around the West to find a rural piece of land where we could build a meaningful civilization. I had raised a couple of thousand dollars selling the last of the marijuana crop, and we took off for Montana.” By going rural, and especially in heading west, Bernofsky bucked a trend being set by his contemporaries. Ever since World War I, rural Americans had been migrating into the cities as technology wrought a sea change in farmer productivity. During the fifties, the nation lost more than 1.6 million farmers, and almost 1 million more during the sixties, thanks to mechanization. A few months before Bernofsky’s departure, Time reported that the population drain was most pronounced in the West: “Fewer and fewer Americans, about one out of three, live in the great outdoors now celebrated almost entirely in never-ever television westerns. In a curious miracle of abandonment, Americans have become strangers in a landscape that they believe has built their national character.” (p. 54)

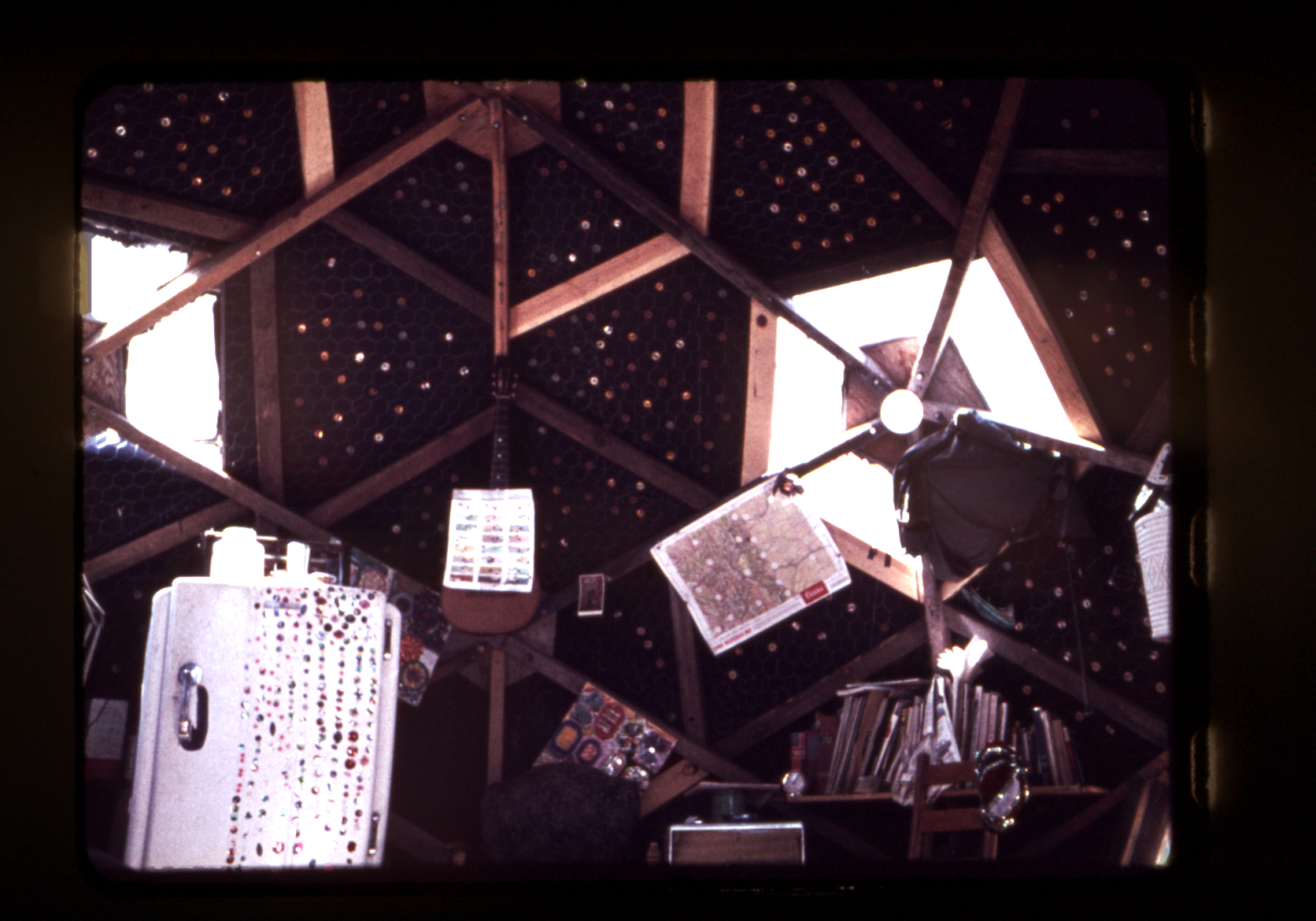

Photo from the triple-dome complex. Courtesy: Richard Kallweit.

Instead, the droppers ended up in Trinidad, Colorado, where they bought a plot of land.

While working on the structure [of the first dome], Bernofsky and Richert often discussed what they should name their new community. For inspiration, they went back to their undergraduate days when they had started dropping painted pebbles from the rooftop of the building on Massachusetts Avenue down to the sidewalk in Lawrence, Kansas. Once a dropper, always a dropper, and Drop City instinctively rolled off their tongues.

“Those were the real roots of Drop City”, Bernofsky said. “The dome was our first official dropping. This was going to be Drop City, and we were going to be droppers. We felt as if we were functioning within the cosmic forces so much that we were actually influencing them.” (p. 73)

Around 1962, Gene Bernofsky and Clark Richert, students at the University of Kansas, developed an artistic act that consisted of dropping objects from their second-floor apartment onto the street below. These Droppings inspired the name they later gave to the settlement they initiated together with JoAnn Bernofsky after buying a 7-acre plot of land in Colorado in May 1965. They were soon joined by Richard Kallweit, and later also Charlie DiJulio and his family, followed by Peter Douthit and other artists, writers and inventors joined the first rural hippie community. Drop City's constructions were based on R. Buckminster Fuller’s geodesic domes and the designs of Steve Baer, a pioneer in geometric structure and solar energy, who built the domes together with the Droppers.

Visual Natures (maat, 30/03–05/09/2022) is the product of more than two years of critical investigations around climate science, creative practices and eco-politics. A continuation of the data-driven installation Earth Bits – Sensing the Planetary and the public programme Climate Emergency > Emergence, both conceived and ignited by Beatrice Leanza during her directorship of the museum, the project surveys political, social and cultural forms of collective agency from the 1950s onwards that demonstrate how our understanding of “nature” informs the ways in which we organise, sustain and govern our communities as an expanding planetary construct, in concept and in practice.

On maat ext., the series #groundworks introduce the critical explorations that feed into the complex interconnectivity between the environmental and energetic quests and its reverberation through decades of artistic creation and cultural dynamics, traced from the 1950s until today, and continues these investigations through collaborations with artists, curators, archivists, researchers and activists on their work and the meanings of ecology, environmentalism and societal responsibilities in the face of climate change.

Explorations is a programme framework (maat, 2020–2022) featuring a series of exhibitions, public and educational projects delving into the multi-faceted subject of environmental transformation from various scholarly and experimental vantage points – it brings philosophical and political perspectives forward, as well as sociocultural and technological investigations interwoven in speculative and critical practices in the arts and design at large. Central to this discursive and critical effort was the establishment of the maat Climate Collective in 2021, chaired by T. J. Demos, and geared toward assembling diverse cultural practitioners working at the intersection of experimental arts and political ecology.