1. The Site

Old paintings and local stories (→ 1) show it was a simple seashore, one where fishermen moored their boats and practised seafaring with the help of their women and children.

Many distinctly speculative proposals for a sea fill demonstrate how the late-eighteenth-century ambition to build a waterfront infrastructure would destroy the Riviera di Chiaia’s age-old eco-systemic balance.

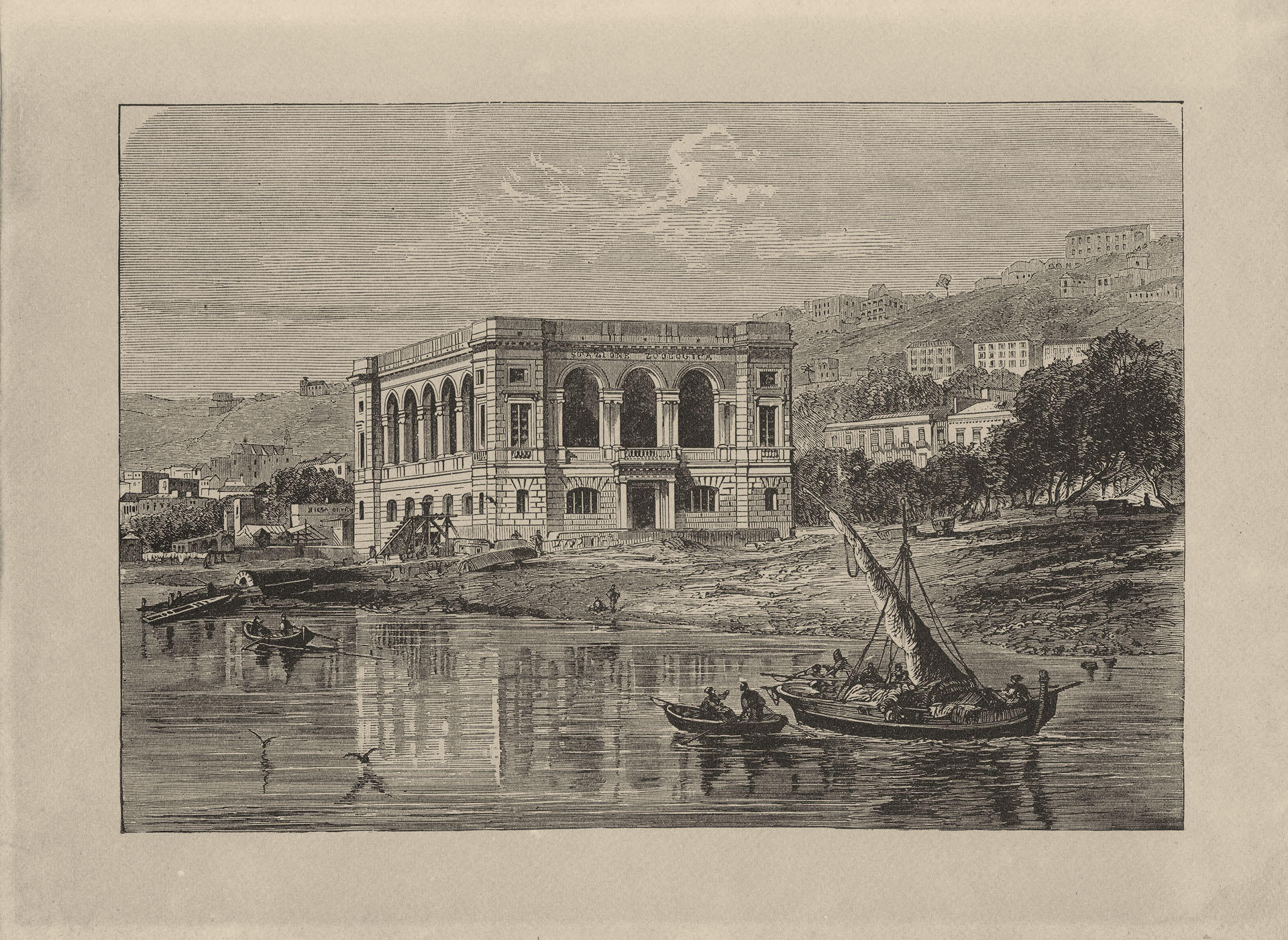

The International Maritime Exposition was inaugurated at Mergellina in April 1871. In addition to a grotto aquarium, a large wooden structure hosted a gallery for navigation machines, generators, surface condensers, superheaters and telegraph signalling. Among the visitors was Anton Dohrn, a German naturalist and zoologist who imagined a network of biological research stations located along the European coast: Naples, Messina, Gibraltar, the Cape Verde Islands, the Portuguese coast and Ireland. Scientists could stop off, collect materials, carry out observations and experiments, and move on to the next station.

Naples would be the pathbreaker. “The building material is nearby with the tuff for the caves in large quantities on Vesuvius; you have fresh sea water in front of the door and thousand animal in the sea and cheap to access.” (→ 2) Dohrn managed to persuade the municipal authorities to give him a piece of land in the Royal Park free of charge in order to erect a zoological station.

The Aquarium building opened on 26 January 1874 and was the largest of the European aquaria in vogue at the time: 250 m³ with 25 tanks, compared to the 12.73 m³ with 14 tanks of the Paris Aquarium at the Jardin d’Acclimatation or even the 100 m³ with 50 tanks of the Berlin Unter den Linden Aquarium.

The aquarium's tank dedicated to the Echinoderms (hedgehogs, stars, lilies). Photo by Johannes Sobotta, courtesy of Stazione Zoologica di Napoli (SZN).

(1) The name Mergellina comes from the legend of a fisherman falling into the sea to reach a mermaid. In Matilde Serao, Leggende napoletane, 1881.

(2) Letter from Anton Dohrn to Fanny Lewald and Adolf Stahr, 13 January 1870 [ASZN: Ba.1265]. C. Groeben, Sotto sarà una pescaria…, in various authors, L’acqua e la sua vita, Pietro Redondi (ed.), Guerini Associati, Milano 2010.

Excerpt of the plan of the city of Naples, 1862. A sketch by Anton Dohrn of the first building location. In R. Florio, “L'Architettura delle Idee. La Stazione Zoologica Anton Dohrn di Napoli”, Artsudiopaparo, Napoli 2015, pp. 58-59. Courtesy of Stazione Zoologica di Napoli (SZN).

Engraving of the Zoological Station's first building on the Chiaia shoreline. Photographer unknown, courtesy of Stazione Zoologica di Napoli (SZN).

“Sciavecuoti” of Mergellina that retrieve the “sciàveca” by hand close to the Naples Zoological Station. Photo: Wilhelm Giesbrecht, courtesy of Stazione Zoologica di Napoli (SZN).

2. The Fishermen

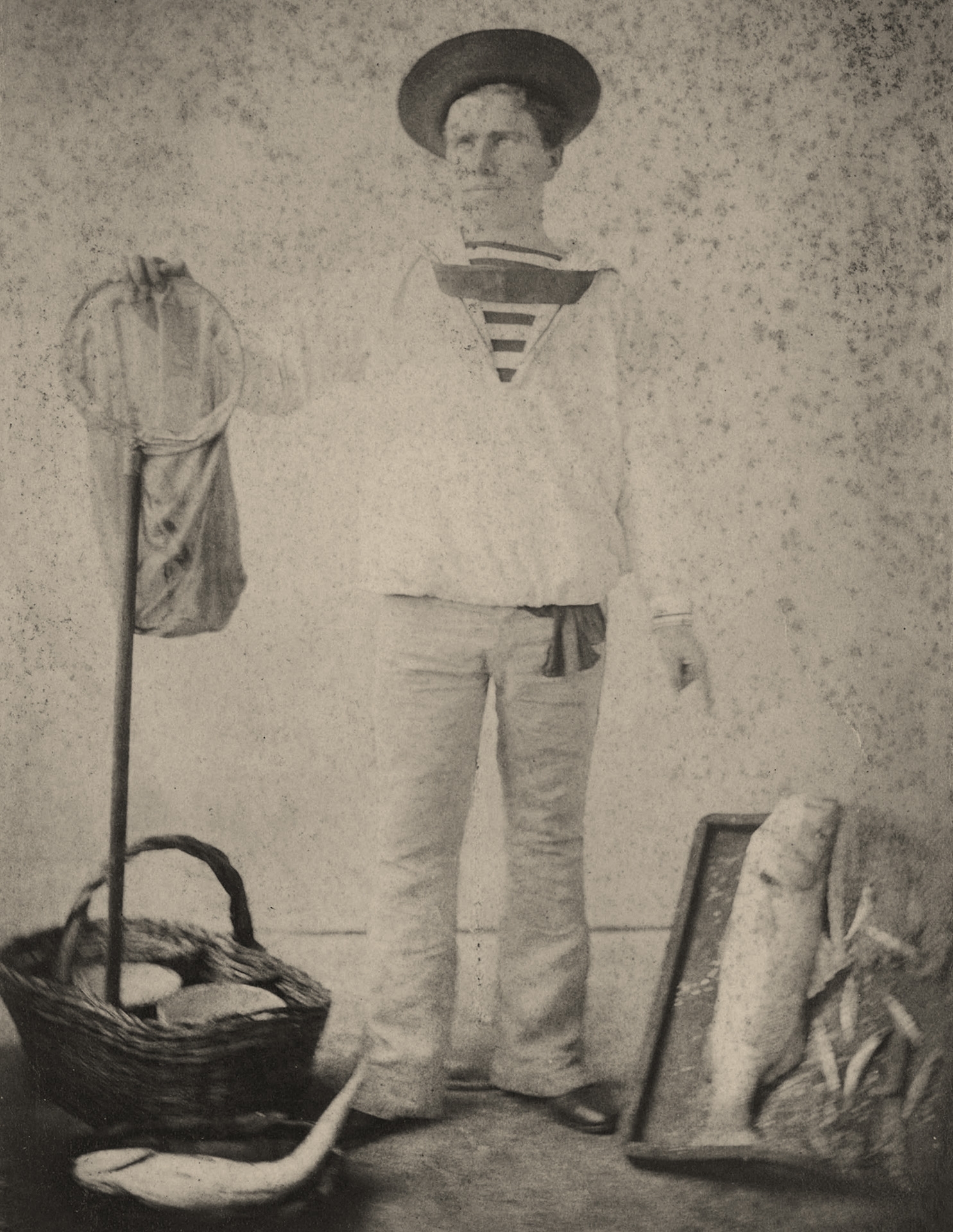

Studies (→ 3) carried out on the seafaring population in Naples in the first half of the nineteenth century report 1,129 fishermen, 2,926 sailors, 437 fishmongers and 383 boatmen, accounting for 1.35% of the whole population in 1845. What finer human resources might one wish for to run an aquarium?

The Institute employed a fair number of fishermen on a stable basis right from the start and dedicated an entire fresco by Hans von Marées in the Library room to their virility, sensuality and massiveness.

Each station’s boat called for a crew of six to eight people, for a load of about sixteen tons. At work there were rowers, sciavacuoti, (→ 4) coffajuoli, (→ 5) nassajuoli, (→ 6) rastrellari, (→ 7) cordaioli... (→ 8) The figure of the fisherman was to become part of a scientific-productive cycle, reflecting the transformation that the fishing profession was undergoing at the time. Subsistence fishing, with technical methods offering low productivity but compatible with the reproduction of resources, was progressively replaced by proto-industrial fishing, the technical superiority of which led to pressure on fishing resources, upsetting a millenary environmental stability.

-

(3) G. Galasso, “Professioni, Arti e Mestieri della popolazione di Napoli nel secolo decimo nono”, Annuario dell’Istituto Storico Italiano per l’Età Moderna e Contemporanea, vols. XIII-XIV, Rome, 1964.

-

(4) In Italian, it refers to people in charge of pulling the sciabica: a large fishing trawl.

-

(5) Fishermen who fish with the palangreso, also called the coffe.

-

(6) Dropping and hauling the pots.

-

(7) Fishermen who use the rake to extract Lamellibranchs and Annelids from the seabed.

-

(8) Those who repair the fishing nets.

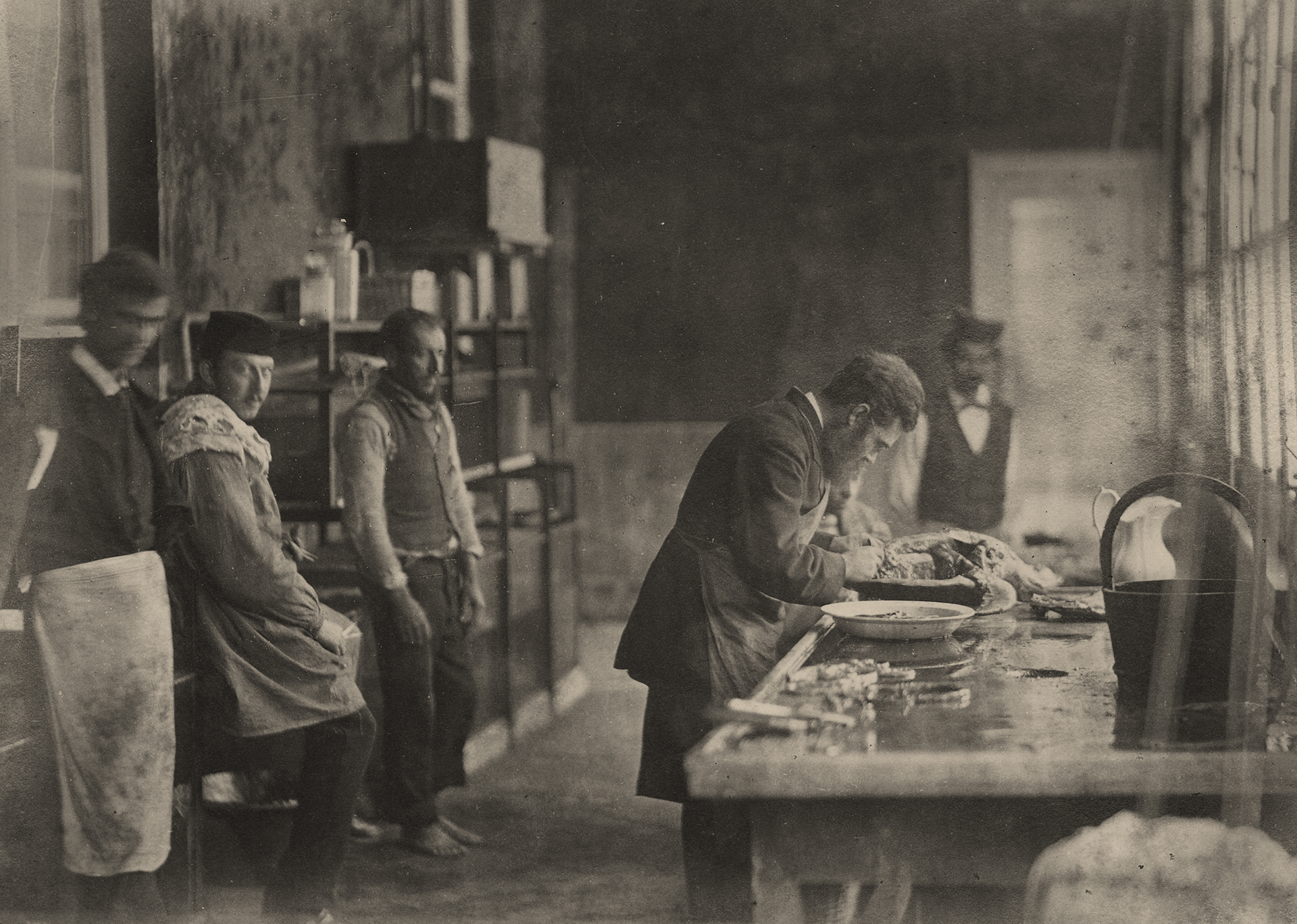

Naples Zoological Station's fishermen team showing the products of a fishing trip. Unknown photographer, courtesy of Stazione Zoologica di Napoli (SZN).

A Zoological Station's fisherman showing mullet, sea bass and pilchard fishes. / Unknown photographer, courtesy of Stazione Zoologica di Napoli (SZN).

|

|

Fishermen on bord the “vuzzarielli” (a small boat with two oars) equipped with white cloth sticks for catching “polipi” and “seppie” (octopuses and buckets). Photo: Wilhelm Giesbrecht, courtesy of Stazione Zoologica di Napoli (SZN).

3. The Fish

“Are they living beings? Are they flowers? Are they monsters? [...] Why does an idea not flash in those millions of cramped brains?”(→ 9) The impatience of the scholars barely conceals the ambitions to access a stretch of coast, which due to its special climatic conditions and the great variety of its seabed, is one of the richest areas in terms of animals and plants. (→ 10) “Of all the Italian coast, there is perhaps no point for marine production as interesting as the Gulf of Naples […] the nature benefits on this most delightful part of Italy must not be lost […] to study how to take advantage of them as much as possible.” (→ 11)

The opportunity of supplying the aquarium tanks with fish directly from the sea in front of it solved the transport issues that were hindering European aquaria due to the high mortality rate of the animals. To gain an idea of the animal’s variety the station captured, it is enough today to visit the room of the Zoological Collection, which hosts about 3,500 specimens belonging to at least 2,000 different species.

Buyers flocked from all the zoological museums of Europe, universities and private individuals to purchase those marine animals that were excellently maintained, thanks to the innovative stabilisation methods developed by the Neapolitan Salvatore Lo Bianco. The Naples Aquarium was also famous for the furnishings of the tanks, made only with natural materials thanks to the naturalist doctor Ignazio Cerio from Capri, who provided the station with stalactites, corals and various types of rock from the island. (→ 12)

-

(9) V. Giordano, L'Aquarium della Stazione zoologica di Napoli (schizzi sulla vita dei pesci) del Dr. Vincenzo Giordano, socio corrispondente della Real Accademia della Valle Tiberina Toscana in San Sepolcro, Stabilimento Tipografico Nazionale, Salerno, 1878.

-

(10) Salvatore Lo Bianco, Notizie biologiche riguardanti specialmente il periodo di maturità sessuale degli animali del Golfo di Napoli, Mittheilungen aus der Zoologischen Station zu Neapel, 1909.

-

(11) Giovanni Targioni Tozzetti, La pesca in Italia, Regio Istituto Sordomuti, 1872.

-

(12) “Sotto sarà una pescaria…”, op. cit.

Salvatore Lo Bianco (the second from right) and his colleagues on board of the Johannes Müller viewing some specimens of benthic invertebrates. Photo: Emil Schöbel, courtesy of Stazione Zoologica di Napoli (SZN).

A diver ready for the catch of invertebrates on the rocks. The diving suit (which was donated by the Italian Navy) was equipped with the oxygen pump and a communication rope. Photo: Eugen von Petersen, courtesy of Stazione Zoologica di Napoli (SZN).

|

|

4. The Equipment

“The ‘palangreso’ is a device formed by a system of cords with hooks that hang at equal distance from a larger horizontal rope, about 400 metres long […]. The palangreso is submerged mostly in deep water, after having baited the hooks with sardines, and is left there for a few hours. The boats used for this purpose are eight to nine metres long, armed with Latin sails and eight crew members. Each boat carries up to 40 palangresi; calculating an average of 100 hooks per palangreso, we have a total of about 4,000 hooks.” (→ 13)

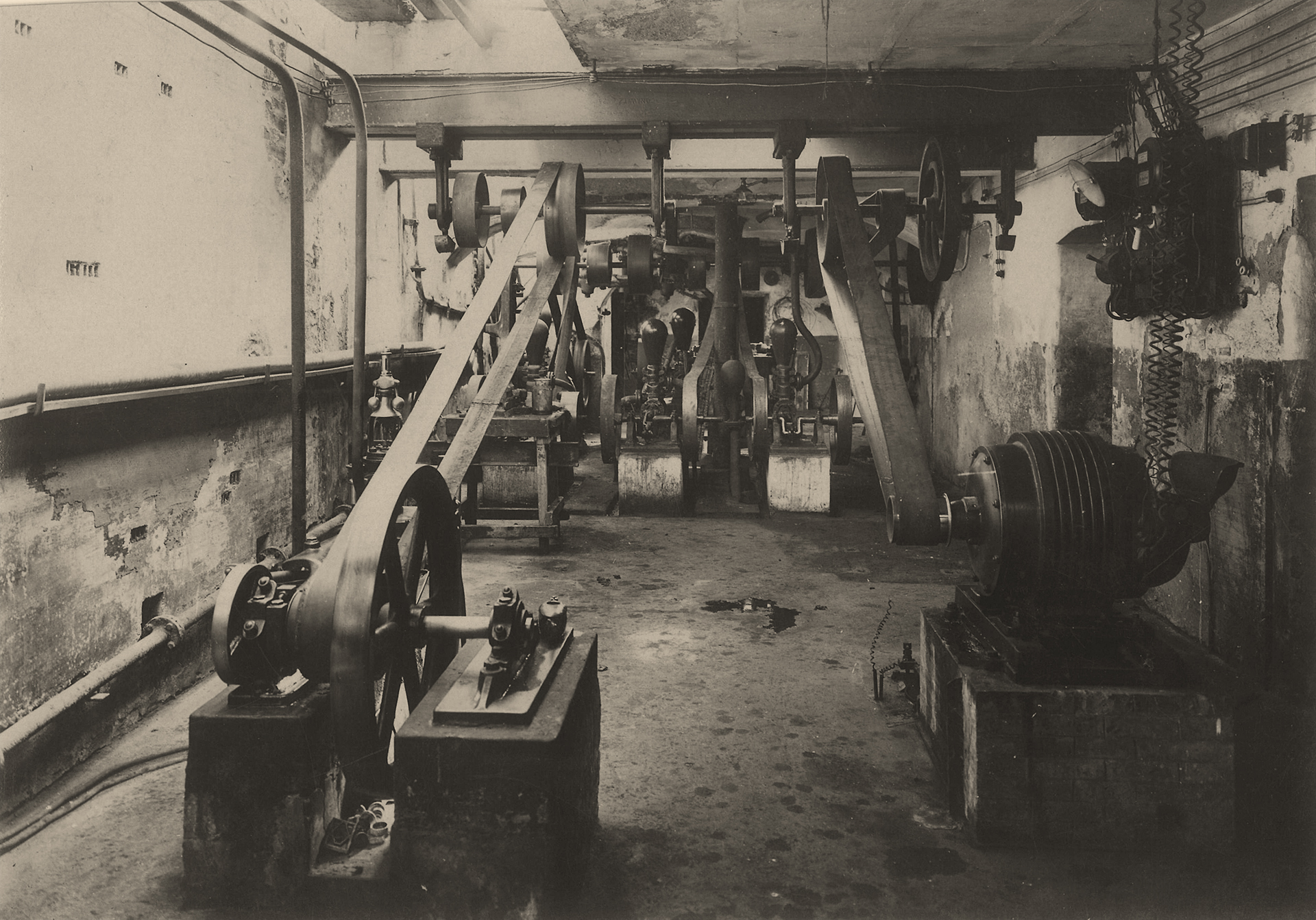

While the description of the fishing equipment shows adherence to local knowledge, in terms of the “quantity of new and complicated tools to be used in the conquest of new submarine lands,”(→ 14) the station turned its gaze abroad, thanks to exemption from custom duties granted to Dohrn by the Italian Ministry of Finance. The entire machinery sector was brought in straight from London. The steam engines and boilers, the pumps and pipes were ordered from the Leete, Edwards & Norman Company, as were the panels of glass for the tanks (with FR. 1,500 to be paid in broken glass in June 1873).

Ernst Abbe, a mathematician, physicist and partner of Zeiss, made it possible to purchase microscopes and other optical equipment with a substantial reduction in price. In return, the station researchers pledged to suggest ways to improve the instrumentation... as well as to promote Zeiss within the international scientific community.

-

(13) “Notizie biologiche riguardanti…”, op. cit.

-

(14) “L’Aquarium della Stazione zoologica di Napoli”, op. cit.

The big machine room in the underground. The electric pumps raised the sea water to the upper floors. Unknown photographer, courtesy of Stazione Zoologica di Napoli (SZN).

5. Architecture

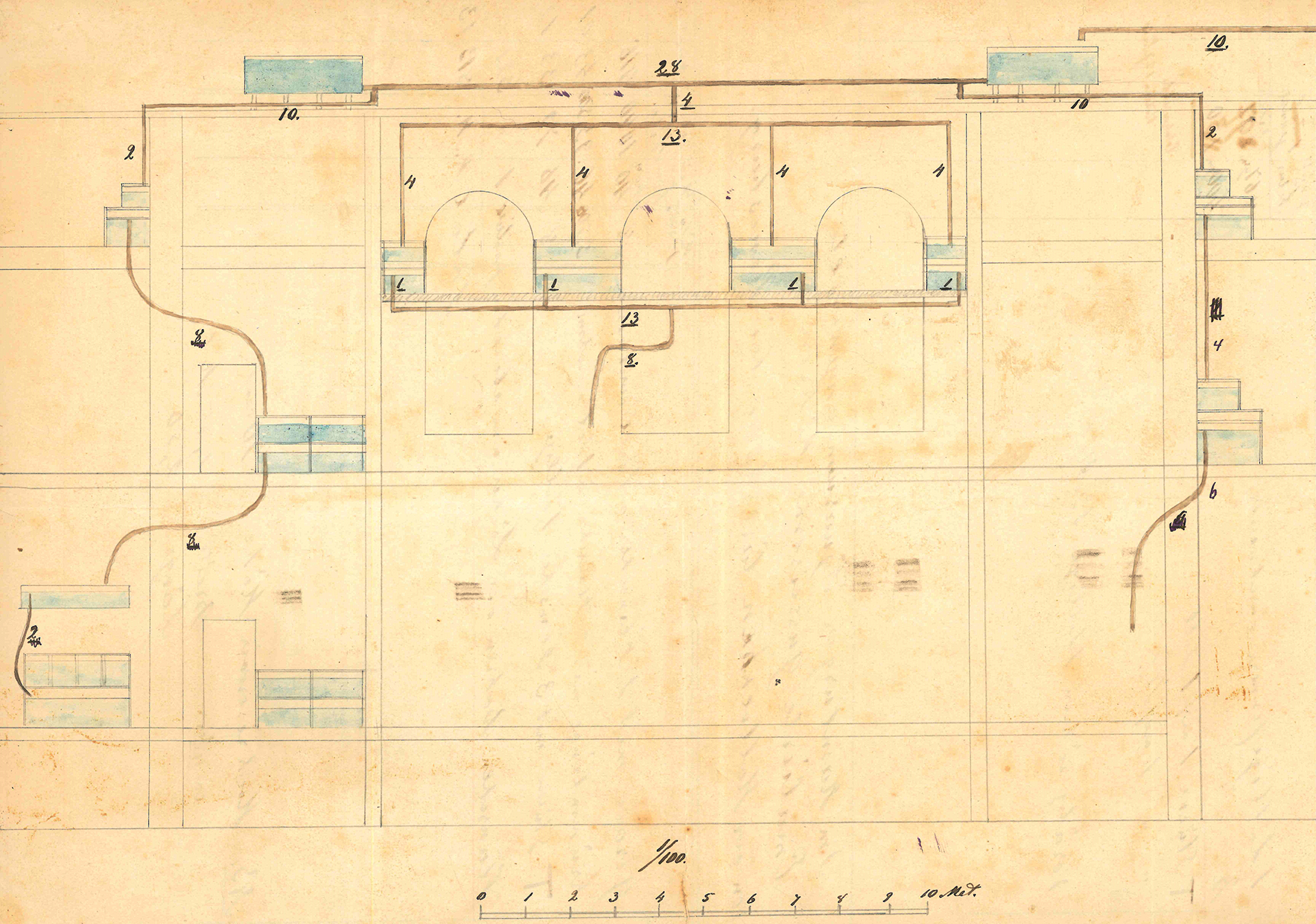

The main level of the building’s section is the sea itself, the water supply from which supplied the entire aquarium building. The amount of sea that ran throughout the building was about 63m³ in summer and 31m³ in winter.

In the basement, an eight-horsepower steam engine with boilers from the Howard system drove a system of five Garven piston pumps and a Jaeger rotary pump that sucked up water through an iron pipe. After settling in a sedimentation basin, the water was pushed by other pumps into a tank on the third floor, where water and oxygen were made to descend into the aquarium tanks by means of a system of vulcanite pipes. A long and narrow water basin located in the basement served as a fish deposit.

The aquarium itself occupied the ground floor. Marble sills and turned wooden handrails ran along 60 arched compartments hosting the tanks. Large panes of glass closed the tanks full of sea water, built between the internal wall of the aquarium and the external wall of the building. Light was provided by the skylight on the roof of the building.

From the upper floor to the mezzanine, the coupling of art and science shaped the architectural form: the large laboratory and the library room were separated by the patio cavity, with small rooms for scholars and the caretaker placed all around it.

The aquarium’s water system plan. Courtesy of Stazione Zoologica di Napoli (SZN).

The completion of the wall structures of the station's third building. Photo: Emil Schöbel, courtesy of Stazione Zoologica di Napoli (SZN).

Zoologist Richard Schmidtlein working on a sea turtle's necropsy. Unknown photographer, courtesy of Stazione Zoologica di Napoli (SZN).

6. The Capital Investment

“Anyone who is not sufficiently familiar with these things cannot imagine what serious expenses are necessary for such an establishment. The Zoological Station, to get a fairly correct notion of it, can be compared to a factory [...] with the only essential difference that the Station, from a economic market perspective, is definitely a bad business.” (→ 15)

In 1880, the Station represented a capital outlay of about 500,000 lire with an annual budget of about 100,000 lire. The aquarium contributed to maintenance with a contribution of about 20,000 a year (just a fifth), with the rest coming from grants, especially given by the German government, Italy, England, Russia, Holland, Switzerland and Belgium. The search for economic independence could therefore not be separated from political pressure.

The laying of the foundation stone was made possible thanks to the English naturalists and many enlightened entrepreneurs, such as the engineer Werner von Siemens from Hannover. The grants served to guarantee a presence at the working tables: in the laboratory, half of the seats were reserved for governments (Germany, England, Russia, Holland and Switzerland) and universities or scientific associations (University of Cambridge, British Science Association, Kurfürstlich Akademie der Wissenschaften), which paid a fee, as did the researchers, who were in fact tenants of the station.

- (15) “Guida per l’Acquario…”, op. cit.

Shelving with marine animals preserved in liquid in the educational museum attached to the aquarium. Unknown photographer, courtesy of Stazione Zoologica di Napoli (SZN).

7. Marketing

To maximise the aquarium’s revenues, Dohrn did a lot of work on marketing. With a calculation of 15,000 tourists (41 per day), the capital invested would be made back by 1887; with 20,000 (53 per day) by 1882, and with 25,000 (68 per day) already by 1879.

The Zoological Station was included in the most prestigious tourist guides of the time, such as the German Baedeker in 1874. A special guide to the aquarium in four languages (Italian, English, French and German) was immediately published, containing a prestigious atlas of 47 ink drawings commissioned from the Neapolitan painter Comingio Merculiano.

The visitor could also buy posters representing views of the aquarium produced by Merculiano; postcards with photographs of the tanks created using a new flash technique by Johan Sobotta; collectible photo albums commissioned from leading professionals, such as Georg Sommer and Michele Amodio.

In conclusion, the few studies on aquaria in the architectural perspective, (→ 16) carried out to date, have focused on the self-contained and self-sustaining character of this typology of architecture. The design specificity of reproducing nature ex situ differentiates the aquarium from other land-oriented structures such as botanical gardens and zoos.

Drawing on Sloterdijk’s spherological theory and the concept of an absolute island, (→ 17) the architecture of the aquarium has been studied not as the location of a building in the environment, but the installation of an environment in a building.

However, the analysis of this case study (the oldest in Italy and the second in Europe), highlights how, on the contrary, the aquarium exists and acts as a result of the continuous flow of interconnected heterogeneous actors – both human and non-human – that led the architecture to expand beyond the building site in order to reach a more global scale. Indeed, the aquarium shows itself to be a network. (→ 18) The extraction of salt water; the tools for catching fish; the network of animal exchanges and sales; the international investments in instrumentation; the economic market feeding this institution, etc.: they all contribute to defining what Dohrn called a perfect “scientific factory,” (→ 19) far from being an architectural structure resolved within itself.

This perspective shows how, since the constitution of the natural sciences in the eighteenth century, modern nature has been endowed with political-economic ambitions, which bring out a managerial approach to the resources of nature in view of long-term human benefit and productivity over time.

The architectural project therefore takes on a precise role in defining the relationship between nature and culture, where the aquarium proves to be an interesting specific case through which these theoretical premises may be expanded upon.

- (16) B. Brunner, D. Doordan, R. Ghosn, E. Jazairy, H. N. Humphreys, N. Kisling Vernon, J. Ryan.

- (17) P. Sloterdijk, Foams. Spheres Volume III: Plural Spherology, Semiotext(e) / Foreign Agents, MIT Press, Cambridge, Massachusetts, 2016.

- (18) On the concept of network, see Michel Callon, Madeleine Akrich and Bruno Latour's contributions on Actor-Network Theory (ANT).

- (19) “Guida per l’Acquario”, op. cit.

maat and Martina Motta would like to express their gratitude to the Stazione Zoologica di Napoli (SZN), in particular to Andrea Travaglini and Christiane Groeben, for providing all the images.

Martina Motta is a researcher based in Torino. Her research investigates the role that infrastructure, extraction and resistance has played on the transformation of nature, with a specific interest in archival practices. She has worked on research projects, collaborating with Manifesta12 - European Biennial of Contemporary Art (2018), Oslo Architecture Triennale (2016), Venice Architecture Biennale (2021 and 2014). She integrated the team at OMA – Office for Metropolitan Architecture, Rotterdam, and currently she is a Ph.D. candidate in Architecture at the Politecnico di Torino with a research project on wood as a conflict element between local communities and institutions. Martina Motta collaborated in the Aquaria – Or the Illusion of a Boxed Sea exhibition as researcher and archive assistant.

“maat Explorations” is an ongoing programme that delves into the socio-cultural and environmental transformations concerning the current bio crisis and ecological destruction, providing insight into the hard science of climate intervention and the creative speculations behind innovation-led research to safeguard our planetary co-existence.

The exhibition Aquaria – Or the Illusion of a Boxed Sea (maat, 18/03 – 06/09/2021) reflects on the possibilities and new questions that arise when rethinking our relationship with the marine world. Curated by Angela Rui, the exhibition path unfolds through 11 installations offering different points of view to emphasise how the ways of understanding the marine environment were once designed and how they should be reconsidered today.