|

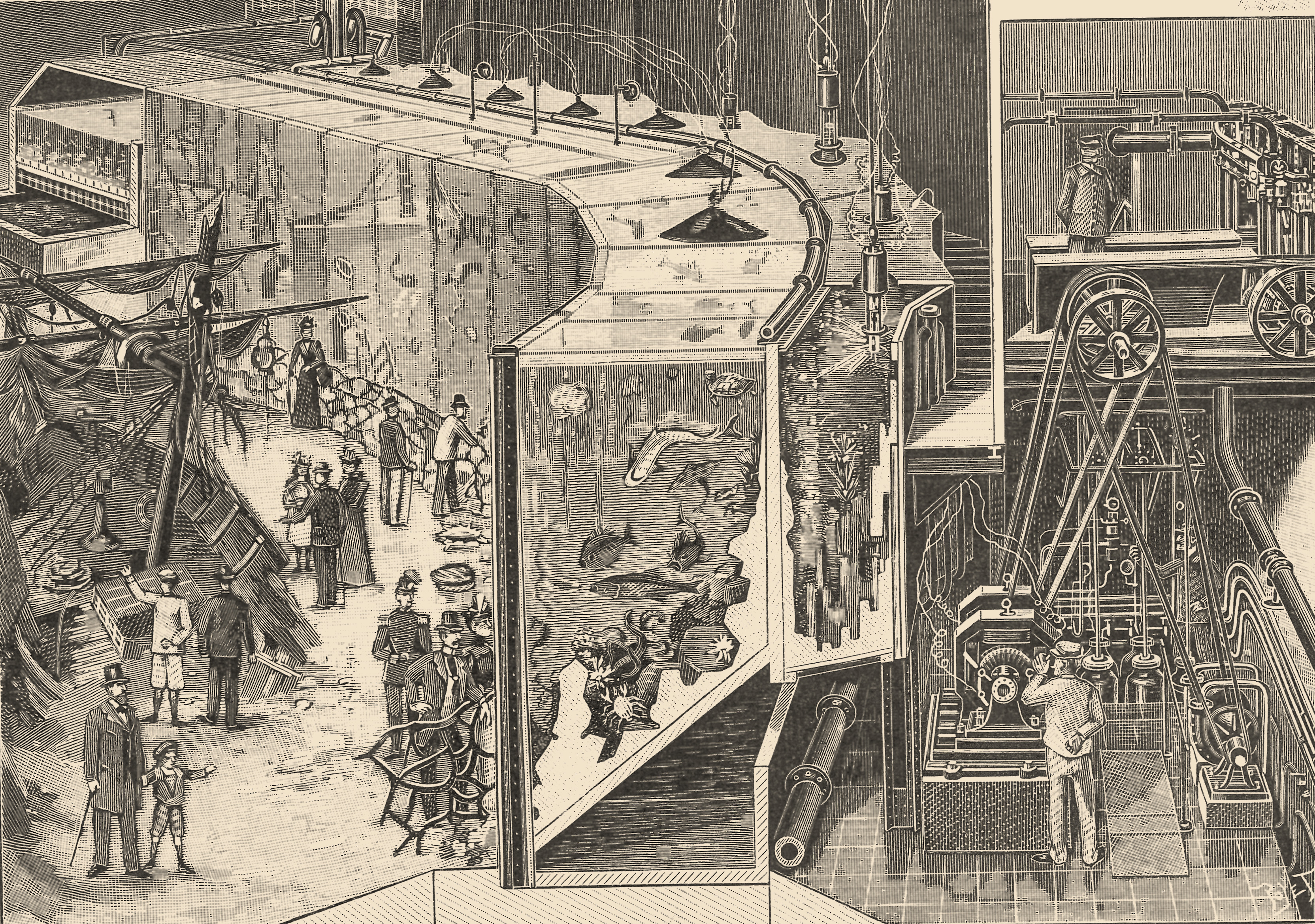

The "Aquarium de Paris”, designed by Albert and Henri Guillaume in occasion of the L’Exposition de Paris 1900. “La Nature. Revue des sciences et de leurs applications aux arts et à l'industrie”, no. 1415 (7 July, 1900), Paris: G. Masson, 255. |

|

Aquaria – Or the Illusion of a Boxed Sea

Angela Rui

After cats and dogs, fish are now the third most popular type of pet, but once removed from their natural habitat, transported around the world and sold as domestic companions, their lives start to depend entirely on the object that contains them: a glass box designed to host living creatures unable to survive outside it. Therefore giving rise to an animal-object coupling: a self-contained world and a techno-natural assemblage, all neatly integrated into our home furnishings.

Invented in the Victorian age – and responsible for a social phenomenon that became known as the “aquarium craze” – the domestic marine fish tank has never gone out of fashion. It continues to constitute an ocean diorama and private zoo, hosting a living collection that serves as our own personal representation of a very fictional marine world.

Aquaria – Or the Illusion of a Boxed Sea is an exhibition that looks at how the ocean has washed up inside our cities, whether in our homes, dentists’ waiting rooms, shopping malls or our cultural institutions. The process of interiorisation of the ocean kingdom – from the inward-looking object of public spectacle to that of home entertainment, right through to our own abstract mental concept of the ocean itself – is intrinsically bound up in our colonial and scientific notion of the taming of nature, converting wild animals and plants into integral parts of the household.

At the same time, the very shape of the fish tank itself reminds us of the cabinet of curiosities: whether it contains animals or plants – the objects placed within for observation – they function through the mediation of glass walls, a material manifestation of our separation from what lies beyond, re-evoking those nineteenth-century patriarchal and colonial missions that sought not only to take control of animals from exotic or faraway places, but also to create visual narratives for the communication of knowledge.

After months confined in our homes, to some degree we too are metaphorically floating inside isolated techno-tanks of our own, from which the world is now experienced in the form of image-based communication through the glass walls of our computer screens. As often our only form of contact with the outside world, our fishbowl existence now begs comparison with the aquatic dimension we have created, once more calling into question our terracentric relationship with the sea sphere and the sense of detachment from nature inherent to both.

Therefore, the aquarium here is conceived as the conceptual object that allows us to lay bare the hierarchical mechanisms that have underpinned our culture of living outside of nature, and which also need to be revised through the deconstruction of linguistic and visual practices. The term “illusion” found in the title of the exhibition refers firstly to the impossibility – in this particular moment of a global pandemic – of perceiving humans as biologically isolated from the environment. Paradoxically, it is the very need for isolation that brings home our indissoluble bond with nature.

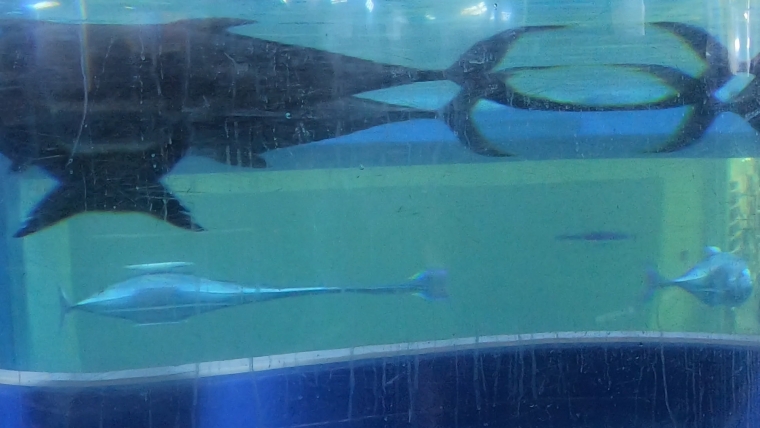

Secondly, it is illusory to think that the portion of the sea which is extracted, walled in and controlled, the water of which mimics seawater through the addition of artificial chemicals actually is the sea. It is perhaps a conceptual sea, spatially represented by living animals removed from their vast natural environment and specific community. And in turn placed into a fictional, limited (and boring) social experiment, unable to communicate the dynamic nature of the sea itself – made up of tides, currents, waves and depths to swim through. Thus, the catatonic rhythm of time that characterises aquaria is a mere shadow of a sea that is a far cry from the ocean.

The blue itself – that colour through which the human species identifies the liquid dimension of the planet – is even intensified by the specific lights and paints used both in domestic and public pools and aquaria, which would appear to bring about a sense of calm in the human body.

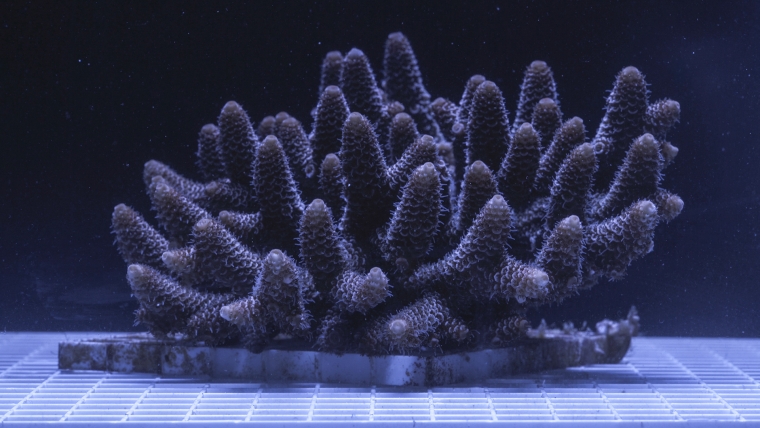

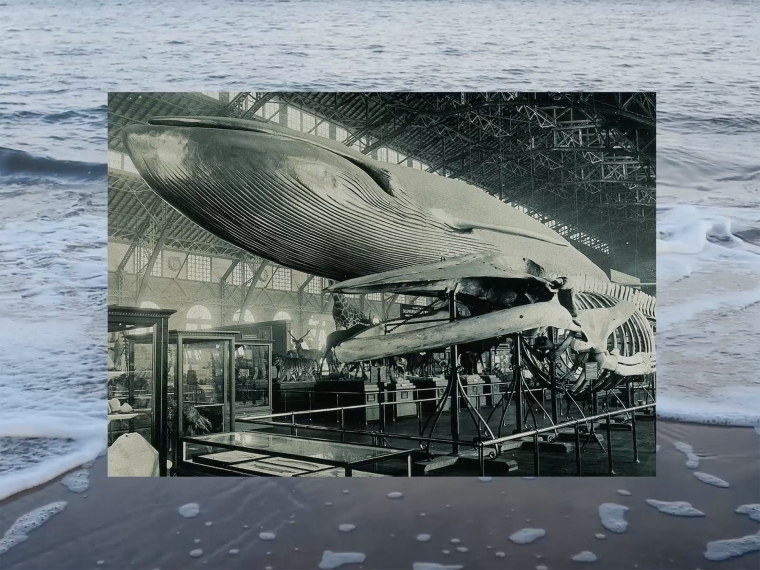

Lastly, the architecture of the aquarium, ever since the nineteenth century, may be interpreted as a complex staging machine: thanks to the sophisticated climate control of the environment and improvements in technology (such as large, transparent and very high-performance viewing screens), the architecture melts away, and the sense of water and life inside the water begins to dominate the view. In the darkness of public aquaria, and in the ever-growing sense of total immersion, the common ground between aquarium and stage is intensified, letting the seamless sense of theatre emerge.

So, where should we see from? How should we intervene in this world-making process that takes place when our vision becomes limited by what we see?

It requires a fundamental shift of perspective, in which the culture of design emerges as a critical practice that calls into question our conventional ways of inhabiting and experiencing the world, deployed solely on the basis of human control, the extraction of resources and the exploitation of other living beings. As 98% of ornamental fish are still caught in the wild, the aquarium – as a desiring machine – conceptually contains them all.

Through the orchestration of spatial and audiovisual installations, selected voices and archive materials, the exhibition reflects on possibilities and new issues that any rethinking of our relationship with the marine world might come up against. Art, design and architecture here serve as tools for speculation, highlighting how the modern idea of living outside of nature has today become a paradigm to be deconstructed in order to contemplate a new form of situated knowledge – one in which knowing, feeling, experimenting and communicating potentially foster new forms of solidarity and justice towards others, adopting holistic and more than merely human perspectives.

Organised from the microscopic right up to the transoceanic scale, the path unfolds through eleven new and revised works – presenting just as many ways to examine the interconnection with the aquatic sphere. The contributions embody a series of parallaxes that provide a variety of ways to interpret what appears to be a continuum: insisting on the reiteration of the bidimensional image and that of the screen – which alludes to the two-way mediation of connection/separation imposed by the glass walls of aquaria – the works on show offer specific points of view to reveal aspects that generally remain concealed from our vision or even our imagination.

Thanks to the spatial design by 2050+, and òbelo’s visual identity aimed at wrong-footing the viewer’s gaze by arousing a self-reflective awareness of the ambiguities of perception, the point of view of the visitor is constantly challenged: the installation acts as an exploded aquarium, where the hierarchical relationship between the outer and inner side is neutralised. Here the two domains overlap, thus choreographing the movement of the audience and the associations between various forms of content. The materials used for the installation, typically deployed in the technical spaces of aquaria and for the transportation of marine animals, are all associated with notions of care and violence.

The exhibition begins with Simon Denny’s work – where the screen as a medium is used to contextualise the diffusion of marine imagery both in everyday life and throughout the exhibition. The following first cluster of works opens up the microscopic scale as a window that makes the teeming life in a drop of brackish water poetically tangible (Marjolijn Dijkman & Toril Johannessen), before articulating the different ways – through narratives of oppression or emancipation – of contextualising animals in the ephemeral distinction between subject and object (Alice dos Reis, Eva Jack, Revital Cohen & Tuur Van Balen).

The second group deals with the theme of the staging machine and the architecture of aquaria: from the function of Baroque theatres to the display of living collections – as in the film commissioned by maat from Armin Linke, shot backstage at the Oceanário de Lisboa [Lisbon Oceanarium] – to the works of Joan Jonas, which adopt theatre and fiction as forms of reconciliation with the element, looking at the ritual and magic of an ancient and non-industrialised sea brought back to the present time.

The third section instead returns to the binary nature of the present as it is showcased to us: the film by Michela de Mattei (entirely shot in the Dubai Mall, home to the third-largest aquarium in the world) reflects on the relationship between consumerism and awe, highlighting the affinities between fish tanks or aquaria and shop window displays. While the work by Superflex proposes possible building foundations – for use in a future aquatic climate regime of rising sea levels – as an opportunity to rethink integration between human infrastructure and that designed to support the life of marine species.

While the whole exhibition continually offers specific points of view to highlight the inequalities and challenges of building closed worlds around the sea, Julien Creuzet’s work expresses the global extractive dimension (that of colonial repression, ecological catastrophes and the transportation of both plant and animal species) in the form of an arena for transoceanic transactions and trade.

The exhibition comes to a close with a work by composer Stef Veldhuis, who turns the tables on the visitors’ position. By immersing their heads into an aquarium, the viewers metaphorically become the fish, and are thus able to listen to sounds obtained by translating the data from countless oceanic datasets into music for strings.

The exhibition includes a selection of two-dimensional archive material – some going back as far as the mid-nineteenth century and organised by topic, revolving around the contribution of each artist – which enters into dialogue with contemporary works, seeking out parallelisms that thematise critical Western issues such as institutional policy, the problematic aspects of nature displays, the link with the great Universal Expositions, scientific expeditions and how they are tied to countless colonial and extractive activities carried out around the planet.

Taking on the aquarium as an interface between the human and non-human, the “voices” present in the exhibition – the format chosen by which to do away with the visual dimension, otherwise present throughout the show – give greater depth to the other interfaces insofar as interaction with the marine dimension is constructed and how it relates to human perception. The Listening Glass includes contributions from Derya Akkaynak, Carson Chan, David Gruber, Philippe-Alain Michaud and Filipa Ramos. The collection on site represents the starting point for an ongoing podcast series available at maat ext. and from Spotify.

|

Angela Rui is a curator and researcher based in Milan who works in design theory and criticism. She believes that design is positioned as a critical practice that problematises conventional ways of inhabiting and experiencing the world, and that designers could operate in domains that demand their capacity to translate, raise awareness and visualise challenges and inequalities as well as currently unrecognised collective commons. Among other projects, she co-curated I See That I See What You don’t See the Dutch Pavilion for Broken Nature – XXII Triennale di Milano (2019), and Faraway So Close – the 25th Design Biennial of Ljubljana (2017). She is currently teaching the “Pedagogies of the Sea” course on the Geo-Design Master programme at the Design Academy Eindhoven.

|

“maat Explorations” is an ongoing programme that delves into the socio-cultural and environmental transformations concerning the current bio crisis and ecological destruction, providing insight into the hard science of climate intervention and the creative speculations behind innovation-led research to safeguard our planetary co-existence.

The exhibition Aquaria – Or the Illusion of a Boxed Sea reflects on the possibilities and new questions that arise when rethinking our relationship with the marine world. Curated by Angela Rui, the exhibition path unfolds through 11 installations offering different points of view to emphasise how the ways of understanding the marine environment were once designed and how they should be reconsidered today.

|