Eva Jack’s video installation Parallel Lives II (Whale Watching), 2020, is presented at maat in the context of Aquaria – Or the Illusion of a Boxed Sea.

I have looked for, but never seen a living whale.

Beguiled by their elusiveness, I have sought solace in transient glimpses of the mysterious creature, grasping them as evidence of their strange existence. In fleeting moments of film footage and in photographs, I have seen the whale through the eyes of another. Lifeless in the museum and stranded on the beach, I have seen the whale in death. I have witnessed only small fragments of an impossibly vast animal whose totality seems to evade my gaze. If seeing is knowing, then the whale remains to me unfathomable; for land and sea, life and death separate us. But like the blank space between words on the page of a poem, the whale’s absence says as much as its presence. Emptiness is a vessel for speculation. I examine each disembodied part like an autopsy, not trying to uncover a cause of death but instead how this animal lives.

The story begins where the body ends...

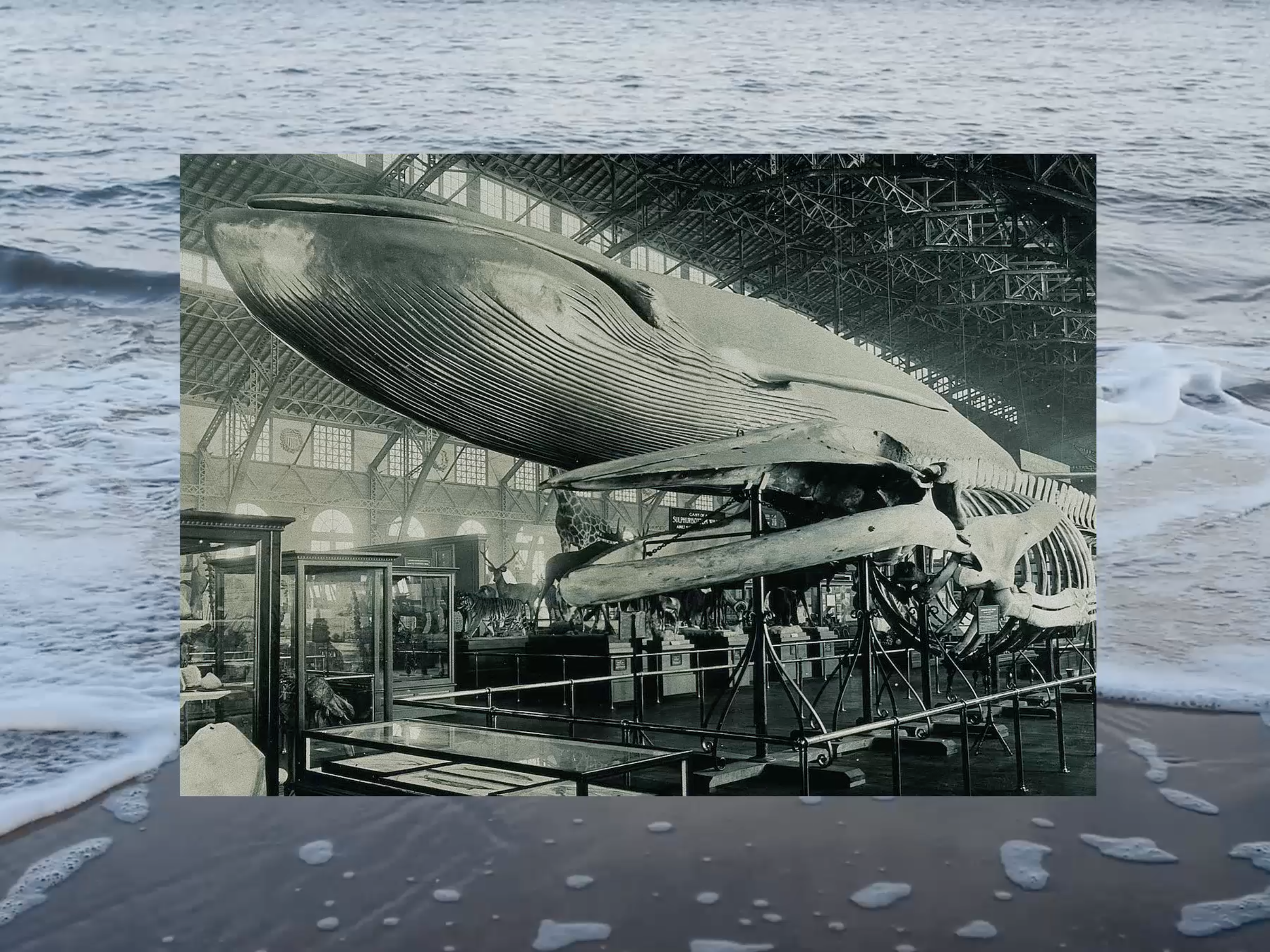

The whale first enters the human imagination when its tail meets the watcher's eyes. In an exit from another world, pushing through the sea’s skin with its own: two bodies, disentangling. From the blue of the sea to the blue of the sky. Rising, to reveal itself momentarily, in the theatre of the natural world, before sinking back beneath the watery veil. Appearing as soon as it disappears, as if avoiding being looked at, the tail symbolises a departure. In death, the most definitive departure of all, the disappearance of the tail plays out most starkly. What remains of the whale's existence hangs lifelessly from the ceiling of the museum, swimming through air. Tracing the length of the spine, I see the body taper off into nothingness, with suddenness. The tail of the whale contains no bones and the rubbery fast-rotting flesh cannot be stuffed or chemically preserved.

Top image: Katu 2 News, 1970.

Eva Jack’s personal footage, 2020.

Museums trespass time, staging the dead as eternally living. But the tail of the whale resists the performative denial of mortality. For such long lives, the loss of this body part is disproportionately quick and permanent, the tail dwells only in the past. Skeletons transgress not only time, but bodily space, offering a strange view of an animal, both inside and out. I am granted permission to travel through the whale, with my eyes at least. From the balcony of the museum, I look at people looking at the whale. They drift around, reduced to the smallness of plankton. Behind fragments of bone, human bodies fill the void with new life. I watch them wander, unknowingly swallowed by the whale. I am reminded of Jonah, who spent three days inside the belly of a whale. He really must have seen this animal… or maybe all he saw was the darkness of the inside of his own eyelids. For even proximity does not guarantee a proper look at the whale. I struggle to imagine being ingested. Disarmed of my power of sight, what remains? The sound of waves crashing against the body like a ship sailing into a storm. The feeling, flesh to flesh, of a mutual 37 degrees of mammalian warmth. The taste of stomach acid, pickling me. The acrid stench of digestion.

Like a lump of stinking ambergris, Jonah was vomited from the whale in a clumsy return to land. But there is no more incongruous exit from the sea than when the whale itself ends up on the shore, spewed out by the waves. The one and only time I saw a whale, it was beached, settled uncomfortably on this patch of sand, around eighteen years ago. It was dead, having succumbed to dehydration or drowning, had the inward tide flooded its blowhole. I was moved by its stillness: it was an enormous wet stone drying and rotting quietly in the afternoon sun. I was not alone, people had come in their hordes to scavenge a glimpse of the unbearably sad show. Graphically, I remember an incision in the belly of the whale, made to prevent the animal from exploding as the body decomposed. From the cut, the whale made an exit from itself, where both guts and dignity spilled out onto the ground.

Museums trespass time, staging the dead as eternally living.

The 1904 World's Fair, St. Louis, Missouri: the US Government building: natural history exhibit featuring a whale skeleton and life-sized whale model, 1904, Wellcome Images.

In the hours that followed, an oversized hearse arrived. It was not black and sombre, but bright yellow with flashing lights. A large mechanical arm carelessly hoisted the carcass into the back. Later, I found out the body had been taken to landfill. Warped, considering most whale post-mortems show stomachs full of human refuse. The rapid clean-up operation made the encounter not only bizarre but brief, heightening the urgency to be there. The mythical beast had fallen without warning, unlikely to do so again. Before long, the incoming tide came and the shore washed its hands of this strange affair. The footsteps, tyre marks, and the imprint of the whale’s heavy body – all gone. Casting into doubt that it ever happened, the sea reclaimed the event for itself.

The stranding came as a warning. The heart of the whale – the biggest heart in the world, a heart bigger than my entire body – sustains a life of up to 200 years. With the capacity to span centuries, an untimely death defies the expectation of longevity, intensifying the loss. A reminder of the whale’s vulnerability in spite of its grandeur.

As the whale plummets in the water, so does its heartbeat, reducing to two beats per minute on the deepest dives. The whale appears to live longer because it lives more slowly, experiencing time differently from humans. Branching from a common ancestor, we have been pushed apart by evolution. Although unrecognisable on the surface, similarities remain in the depths.

The California Gray Whale, National Park Service, c. 1950.

Without its leathery glove of flesh, the whale’s flipper bears an uncanny resemblance to my own hand. A wrist leading down to the fin, an anchor holding four fingers and a thumb. I am looking at another but seeing myself. I imagine us, side by side, reduced to bone, suddenly inseparable; held together by our shared ancestry. “Do not touch” read the signs, harbouring a self-awareness of our own destructive nature. The untouchable hand symbolises the separation between myself and the whale. “Do not touch”, a denial of the fact that everything in this place has been altered by human hands. No touching, only looking. The human gaze turns animals, intelligent lifeforms, into objects.

For a long time, the head of the whale was valued not for its mind but for money. From their severed heads spilt spermaceti. Formed into candles and burnt, whale oil from the blackest seas was the most predominant producer of light for three centuries. Life sacrificed for light. Whales illuminated the darkness and enabled humans to see. Meanwhile the living animal remained assimilated with darkness. Existing in the blacks and blues, most people would never see a living whale, and so relied on the impressions of artists, many of whom had never seen one either. Mystery became the mother of monsters. Their terror was centred around the mouth. Bared teeth, poised and ready to heartlessly obliterate passing boats or human limbs. And so it was ignored that humans kill whales more often than whales kill humans. Conquering the whale became about conquering a sense of human inferiority. Under the pretence that the beast’s almighty power would be reborn inside the human body.

Museums put this conquest on display, proof of the ultimate taming of nature. Still and silent, the whale, finally submissive. Carved on the jawbone, its final living moments immortalise the prelude to its own death. The human narrative overrides the animal’s. From its mouth were once sung songs from another planet. Clicks, cries and moans, exported from the sea to our ears, a modern commercialisation of the whale. Eavesdropping on the language of the other, mesmerised by the void of non-comprehension. Having fallen three white piano keys since the sixties, whale sound has deepened as they struggle to communicate over the tumult of human-made noise. Echolocating their way through the world, noise pollution is not just muting and deafening them, but blinding them too. For whales see with sound.

No touching, only looking. The human gaze turns animals, intelligent lifeforms, into objects.

The Great Whales, National Geographic Society, 1978.

The eyes of the whale are two tiny dots inconspicuously marked on each side of an enormous head. That day on the beach was the closest I have come to looking a whale in the eye; but it came to nothing. I was either too overwhelmed to seek out such small details, or because the desire for visual contact was developed in adulthood. I wonder if the eyes had closed as an impulse to block out the terror of the stranding, remaining shut to embrace death’s eternal sleep and eliminating any chance of seeing itself being seen in such a mournful state. In museums, my gaze has also not been met, or returned. Fragments without faces, skeletons stripped of sight. The only eyes to be seen are made from the same material as the display cases. A complex organ, replaced by a cold inanimate marble. I look at the whale, glass eyes look back.

I too, have not been able to look with my own, but through glass eyes. Witnessed first by another person and then by a lifeless lens; a camera sees the whale. Far off in the distance, but in the right place at the right time; binoculars see the whale. Interrogating the depths of the animal; a microscope sees the whale. These second-hand sightings are never truly mine. From the human perspective, the eye is looked to for connection and understanding. I have believed, eye to eye, I would finally know the whale. But if this creature were to look back at me, the exchange I yearn for might be missing. The whale sees a world without colour, limited to light and dark where detail is diminished to a blur. The smallness of their eyes testifies to the insignificance of this sense for the whale, who connects to the world in ways I will never be able to. Strangely, I have been determined to look at an animal for whom sight is relatively unimportant.

The Great Whales, National Geographic Society, 1978.

In trying to see the whale, the animal itself has escaped into my periphery while my own unknowing has come into focus. Attempting to find meaning, I have built a whale, it lives not in the sea but inside my head.

“Whale Watching” (2020) is a short film that follows the personal tale of an unfulfilled desire to see a living whale. Having never seen this creature for herself, the narrator is forced to look through the eyes of others, assembling fragments of found footage. Using observation, imagination, recollection and research as methods for storytelling the film attempts to construct a picture of the elusive animal while also questioning the motives for doing so.

Eva Jack is a designer and researcher based in Scotland. Her work centres around the strange relations that connect humans and animals. Eva is particularly fascinated by Natural History museums, where entertainment collides with education in artificial re-enactments of multispecies worlds. Given this context, her work does not necessarily focus on the animal itself but instead on their representation, cultural meaning and shared social history with humans. Ultimately, she is led by the question ‘Why Look at Animals?’ (borrowing the title of John Berger’s 2009 book), grappling with the power the human gaze has in turning animals into objects. She gives form to her research through immersive installations and written works. Using tactics like subversion she attempts to question the position of the human, de-stabilising the notion of anthropocentrism.

“maat Explorations” is an ongoing programme that delves into the socio-cultural and environmental transformations concerning the current bio crisis and ecological destruction, providing insight into the hard science of climate intervention and the creative speculations behind innovation-led research to safeguard our planetary co-existence.

The exhibition Aquaria – Or the Illusion of a Boxed Sea reflects on the possibilities and new questions that arise when rethinking our relationship with the marine world. Curated by Angela Rui, the exhibition path unfolds through 11 installations offering different points of view to emphasise how the ways of understanding the marine environment were once designed and how they should be reconsidered today.