Knowing how to differentiate between truth and lies is a problem of our time. An online advertising model based on predicting user behaviour is moulding the way in which we inform ourselves but also how we form our beliefs and validate them. When our opinions are formed without access to verified information, what shape will debate take? And how will we make political choices?

🏁

This text is the transcription of a lecture given by Paulo Pena in the context of “The Daily Post-Truth”, a joint project between the Department of Communication Design of the Faculty of Fine Arts of the University of Lisbon (FBAUL) and maat. The project uses fiction as the basis for a speculative and critical design practice that seeks to question the tenets of the dissemination of disinformation in the post-truth era.

The distinction of truth from falsehood has become a defining issue of our time. It is a problem which affects the quality of our democracies, our lives, and the way we think. But what I would like to suggest to you is that this is our problem, and that we have everything we need to solve it.

It is not, as many have come to believe, just a geopolitical problem stemming from Russian propaganda and the actions of other intelligence services to mire the diplomatic chessboard in unending culture wars. It transcends the trade secrets that give online platforms a key to the inside of each of our heads and the algorithms which predict our every preference and click, insights which have made such platforms some of the most profitable and powerful companies ever seen. It also transcends the failings of weak states, erratic policy making and the lack of regulation. While evidence bears out the influence of all these factors, I would like to propose a slightly less ambitious solution to deal with disinformation; one that does not depend on profound changes to the behaviour of Silicon Valley or governments.

Over the last two years I have seen much more fake news than I would have liked. Me, who thought I lived in a community that had been relatively spared from this global plague… I found highly profitable Canadian businesses making web pages dedicated to spreading misinformation in Portuguese, pages which generated revenues of more than 10 thousand euros a month in advertising alone. I also found European hate speech networks set up specifically to skew election results and to give voice to racist and anti-refugee populism, organised around video channels from the Netherlands and extreme-right politicians from Austria, France, Italy, and Germany, and which then used a vast network of fake accounts in other countries to spread lies about fictitious rapes, assaults and attacks on churches committed by refugees.

When you spend so much time reading this kind of material on social media, you begin to get a clear idea of what's going on around us: the information bubbles we live in; the political polarisation; the sense of fear and incredulity we hear on public transport; the unprecedented results of certain elections; the rush on supermarkets at the onset of the pandemic. But you also realise that the success of misinformation always depends on us, actual people, and on our ability to resist, to be suspicious, sceptical, and to know how to inform ourselves.

This is the optimistic part: if disinformation is our problem, it is we who have to fight it. And we need to do this in the way we manage our privacy and seek information to form our beliefs – all without becoming dependent on a community we rightly call 'virtual'.

Among our greatest qualities as human beings are curiosity and scepticism. If we are sceptical and curious, we won't fall prey to the voice mail I heard on WhatsApp in the early days of the Covid-19 pandemic reporting that the supermarkets would all close in two days and that we should empty the shelves while we can. Likewise, we wouldn't give credence to the posts of a lady with a pretty picture on Facebook who calls herself 'Maria Silva', but who we've never met, despite supposedly having hundreds of friends in common.

There are simple techniques we can employ: don't click on links to sites you've never heard of, especially when the headline seems stranger than fiction. If we do make that click we're financing that site with real money, advertising money. And we're giving them some extra points in the network algorithm, ensuring that same link will be shown to more people. Worse, if we click on that kind of site, the network algorithm will then predict that we'll click on any similar links they put in front of us. And this is the vicious cycle that explains the problem. We quickly get caught in a bubble. Do an experiment yourself to see if what I say is true: for just a few weeks, exclusively open links in your feed that deal with a specific topic (I experimented with football, but you can be more discerning). After a few days, your feed will be filled almost entirely with news related to this topic. In the end, your information world will shrink. The effect of this is that we soon begin to depend on these messages. The information we consume shapes the way we see the world. Never forget: we are consumers and there are people professionally dedicated to coming up with ways to keep us consuming.

This is the optimistic part: if disinformation is our problem, it is we who have to fight it.

Now for the more pessimistic part. It is we who feed the disinformation network.

Now for the more pessimistic part. It is we who feed the disinformation network. Albeit carelessly, and almost always with good intentions. Invented by obscure political and economic interests, and placed in our feed by bots, skinheads or advertising agencies, the ultimate goal of this entire network is for us to lend our credibility as friends, children, parents, uncles, aunts and siblings by sharing such misinformation.

Through this mechanism, we are unconsciously creating a dystopia. A community where we do not share the basics. Whatever you think about a given issue (Covid, education, health, celebrities, the war in Syria), there is a single condition required in order for us to rationally discuss it with each other, whether in agreement or disagreement: we all have to share same facts.

I share the same reservations as many of you do: good information is expensive, scarce, and newspapers and television can and do get things wrong. It's true. Journalism today is experiencing an existential crisis. It's a paradox. We have never had so much information at our fingertips; it has never been easier to find documents, explanations and facts. But are we better informed? Studies show we are not.

Information is just another good at our disposal for online consumption, in competition with all the others that make a claim for our limited time and attention (music, movies, TV series, games, chats, photos). Yet information cannot compete for our time with the same weapons that fun and entertainment have at their disposal. Social media, which are essentially advertising businesses, follow no hierarchy as to the social importance of different topics and issues. They just give us what they know will interest us. That's why journalism will only lose the war if it thinks it can seduce us with trash 'news' based on the same online tactics as recipes by celebrity chefs and the latest on Game of Thrones.

The journalism we need is often boring, explanatory, and too long to read on a mobile phone while waiting at a traffic light. This journalism takes time, has rules and doesn't always go 'viral' according to the voracious metrics of online reach. Today, unfortunately, many newsrooms have given up on this kind of serious news. They prefer to go for clicks, to try to compete for our limited attention. What I'm telling you is not new, and I have one or two more pieces of evidence that support this hypothesis.

Newsrooms have become depressingly uniform in recent years: rows of desks lined up in large open-plan spaces, creating an erroneous idea of absolute transparency. This type of space limits behaviours, in an attempt to demonstrate that everything is public, that everything that is said can be heard by all. I can attest that the effect is actually the opposite. The absence of privacy, of closed rooms to make sensitive phone calls or openly discuss a job or strategy, has taken the most important conversations out of the daily newsroom. When journalists want to talk about something important, they leave the open panoptic space. While working there, they usually wear headphones and listen to music.

But this simple ideology that international media consultants have brought to our newsrooms – no matter its consequences for journalistic practice – has only become irreversible thanks to a single prop: one or two large screens, usually fixed on a central wall, that show graphs with a set of rapidly changing numbers. To make it easier to understand, let's use the name of the company that created the best known of these measurement systems – Chartbeat – though other suppliers of such charts include Google Analytics. Indeed, several such screens from different suppliers can sometimes be found on the same wall. A constant feed of 'online traffic metrics' has become a ubiquitous image in newsrooms and on the computers of directors, executive editors and even of journalists themselves. And this marks a turning point in the history of contemporary journalism.

Of course, media outlets have always measured their reach with consumers. This was once done through reliable indicators such as the number of newspapers sold and by assessing the opinion of readers through surveys and focus groups. It's not so much engagement that is at issue. Indeed, it remains necessary to analyse the impact that journalism is having, even in an online world which remains somewhat opaque, albeit measurable by fragile means.

But there is a difference between delegating this task to a specialist who reports data to management and doing it in real time and in plain sight. The risk this new mechanism presents is serious: metrics have become a criterion for directing coverage, for determining editorial prominence, and even for self-censorship. Chartbeat makes a claim to offering 'proof' for what works, but this 'proof' is fallible and often wrong.

In recent months, Chartbeat has shown a common feature across media outlets in Portugal: stories on the Chega party and its leader André Ventura are among the most shared material on social media. I have confirmed this with three major Portuguese newspapers.

Chartbeat gave every newsroom a clear message: writing about this party or its leader generates traffic, mobilises readers and expands the reach of the publication. The natural outcome of this understanding, whether consciously or not, is an increase in the number of stories on Chega and Ventura (a trend which I can only confirm through my personal daily experience with news publications, as there is no public barometer of mentions of politicians and parties in Portugal).

Metrics have become a criterion for directing coverage, for determining editorial prominence, and even for self-censorship.

Is it a journalist's job to give the audience what they want? In other words: What is news? Is it just an 'important' story, or is it rather a story that is widely read, commented on and shared? This is a question that plagues journalists all around the world. In his latest book Why We're Polarized, Ezra Klein, an American journalist and founder of news website Vox, explains that it is very difficult to find a clear answer in the US to this fundamental journalistic question.

'In theory, newsworthiness means something roughly like "important." The most newsworthy story is the most important story. But if that were true, front pages and cable news shows would look very different from how they do now: more malaria, fewer celebrities (including political celebrities). In practice, newsworthiness is some combination of important, new, outrageous, conflict-oriented, secret, or interesting. [...] A shortcut to newsworthiness has always been whether other news organizations are covering a story – if they are, then it’s newsworthy by definition.'

The result is a tautology. Klein explains: "Whatever everyone is covering is newsworthy because everyone is covering it."

The result is a tautology. Klein explains: 'Whatever everyone is covering is newsworthy because everyone is covering it.' This is the bait that right-wing "alternative" (alt-right) politicians like Donald Trump and André Ventura use to dominate public debate, even when they are in the minority or almost irrelevant in terms of the objective size of their role in a given debate.

Klein shows how Trump dominated the news even while still a candidate that polls gave little chance of winning the Republican primaries in 2016. 'There were seventeen Republican candidates running for president and Trump received more than half of all media coverage, with the other sixteen candidates sharing the rest.'

This reality can be summed up in a famous quote by the CEO of CBS, Les Moonves, when speaking about the Trump effect before the presidential election that would take him to the White House: 'It may not be good for America, but it's good for CBS.'

As Klein points out, the result is a self-fulfilling prophecy: 'The media doesn’t just reflect the politics we have; it shapes it, even creates it. (...) The media is how most Americans get their information about politics and politicians, and if the media is tilting, or being tilted, toward certain kinds of political stories and figures, then the political system will tilt in that direction, too.'

With legislative elections scheduled for 2023, and thus with very little empirical data at hand, it is still much too soon to extend this kind of analysis to Portugal. But the strategy used by politicians like Ventura seems to be based on that of Trump. And it seems to be having the same effect on the media. André Ventura and Chega received roughly the same number of votes a year ago (less than 68,000) as Iniciativa Liberal and Livre. Each of these three parties has only one representative in parliament.

This should be an important editorial criterion by which to gauge the relative news importance of issues related to Chega and its leader. There are, of course, other criteria too, such as if a party plays an important role in the politics of the day or is in negotiations or coalition with larger parties. Such criteria should be kept in mind especially when the political communication strategy of a given party seems to be based precisely on taking advantage of weak journalistic criteria and deriving notoriety from them.

Trump is, once again, Klein's example: 'He’s shown that in a competitive media environment – particularly one responsive to social platforms – you can dominate the media by lobbing grenades into our deepest social divides. If you announce your campaign by calling Mexican immigrants rapists and criminals, you’ll dominate mindshare among both the people who hate you, whose identity and group you’re threatening, and the people who’ve been waiting eagerly for someone to descend a golden escalator and finally stand up for them and their beliefs.'

In other words, the trick is to master the Chartbeat news metrics regarding what has been most widely read (or mostly widely clicked), thus creating a perception in newsrooms that this is a politician that people like to talk about – or about whom consumers want to know more.

As Trump has demonstrated, there are three ways to do this. The most obvious is to try to create a group of followers that agrees with the politician's most outlandish proposals (chemical castration, nostalgia for dictatorship, Nazi salutes). But this will always be a limited group, unable to dominate the Chartbeat charts.

To succeed, the politician of the alt-right needs enemies. He needs to be the common talking point among his opponents. That's why the policy proposals I described earlier were not intended to win a majority of votes among 'deplorables' (to cite the adjective used by Hillary Clinton during the campaign to describe some Trump voters). Rather, they were proposals intended to be shared on social media, critically, by those who felt threatened by them. To this extent, the victims of populism are the main contributors to its rise.

And if all the above is still not enough, there is a third way to master the media agenda, one that is less well known, and which I have studied, almost exclusively, in my last two years of work: the pure and simple manipulation of online traffic metrics.

Imagine this: if the 68 thousand people who voted for Chega in 2019 were true dyed-in-the-wool supporters of the party and its leader and they all had a great internet connection and laptop computer to share, replicate and comment on the news that interested them on social media, that still wouldn't be enough to make Ventura and his party what they supposedly are on Chartbeat. The problem is the number. 68 thousand Portuguese citizens are not enough to dominate the political debate on Facebook (where there are six million users in Portugal), WhatsApp and Instagram (more than 3 million each) and Twitter (one million).

The answer is simple: just as there are certainly not six million people using Facebook in Portugal, just a small slice of the 68,000 Chega voters can be made to seem like a crowd online. The only thing necessary is to do what we see every day on our social media feeds: create a set of fake accounts. Anyone can create as many accounts as they want. Invent a name, upload a photo taken from the internet, and that's it. These bots are the final and decisive step for the establishment of a proper misinformation campaign. Then you just have to convince real people of what you are spreading.

Social psychologists are currently studying how belief formation has changed since the rise of social media and there are some interesting conclusions in these studies: it is the resonance of a lie (or inaccuracy, or lack of context) which convinces us. We increasingly value information that conforms with something we already think (I don't like politician A, so I find it easier to believe a lie about that same politician). We are receptive to information shared by people we trust (friends and family) and are not so much guided by the objectivity of the information or source itself.

All this should alert us to the growing threat to how our opinions are formed and changed. Giving up on journalism is therefore not an option if we want the truth. On the contrary: we need to make newspapers, magazines, radio and TV return to the old maxim of making what truly counts interesting. And if our demands are not heard, we have to insist on it in other ways.

To be free, both in the real world and in the online media networks (networks which are here to stay, whatever future forms they may take), we have to realise that this problem is ours. We can begin by being sceptical and not sharing fake news, of course. But we must also demand more serious and credible journalism, more journalism with actual substance and less clickbait, journalism with verified facts and social relevance. This type of journalism requires that people pay for it, either through taxes creating public support mechanisms for quality information, or by subscribing to publications, buying from newsagents and donating to crowd funding campaigns.

I don't need to warn you of the risks we run if things keep going as they are. Every day more people believe that the Earth is flat, more politicians making claims that Covid-19 can be cured with injections of bleach are elected, more massacres happen to people such as the Rohingya, and more racism and inequalities flourish around us.

We increasingly value information that conforms with something we already think.

Two years on I can comfortably confirm that the dopamine hit we get from people giving likes to our posts and the praise we get online is nothing compared to the gratification we owe ourselves of refusing to be indifferent accomplices to the destruction of our most important common good: to live freely in a good community.

And to do this, it is enough that we ask a simple question every time we scroll through our feed or find some link in a Google search that shocks us. This question is the most important weapon at our disposal to stop disinformation in its tracks: Should I or should I not share this story?

Paulo Pena studied journalism in Lisbon and Washington DC. He was a reporter and editor at the weekly magazine “Visão”. In 2014, he moved to the daily newspaper “Público” as special correspondent. From 2018 to 2020, he was special correspondent at “Diário de Notícias”. Pena has won several prizes (for his reporting on the G8 Summit in Geneva, the banking crash in Iceland and labour market reforms). Most recently, he won the Gazeta journalism award for his reporting on the Portuguese banking scandal, which was also published as a book (Jogos de Poder [Power Games], 2014). He has written two non-fiction books, one about the students who opposed the Portuguese dictatorship (Grandes Planos [Big Plans], Âncora, 2001) and another about the disinformation machine and the power of online platforms (Fábrica de Mentiras: Viagem ao Mundo das Fake News [The Factory of Lies: Factory of Lies: Journey into the World of Fake News], Penguin Random House, 2019). He is one of the founders of Investigate Europe, a team of European investigative journalists.

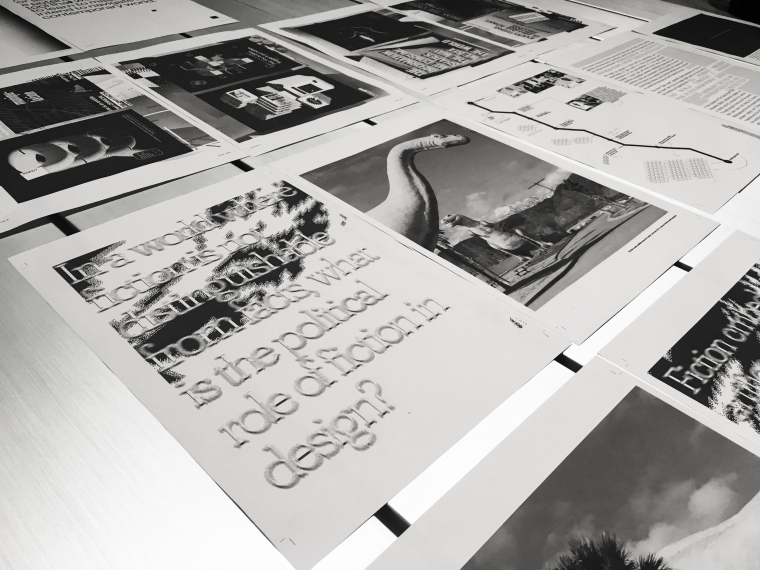

The Daily Post-Truth is a joint project between the Communication Design Department of the Faculty of Fine Arts, University of Lisbon, and maat, developed within the scope of “maat Mode 2020” programme. The project is motivated by a renewed interest in fiction, within artistic practices and design in particular, as one of the discursive modes that is best able to restore a sense of reality in an age governed by post-truth. Within this context, the newspaper, as one of the media that most evidently suffered the effects of disinformation, becomes prone to appropriation and recuperation. By creatively exploring this publishing model in crisis, while focusing on the tensions between truth and post-truth, fiction and reality, “The Daily Post-Truth” proposes the development of its own newspaper, through a sequence of four different stages.