Black Mountain Theater

John Cage’s Theater Piece No. 1 and the Performance of Ecological Convergence

Tyler Cole Laminack

Echoing the “Groundworks” timeline: 1952

I am interested in any art not as a closed-in thing by itself but as a going-out one to interpenetrate with all other things, even if they are arts too. All of these things, each one of them seen as of first importance; no one of them as more important than another.

John Cage (→ 1)

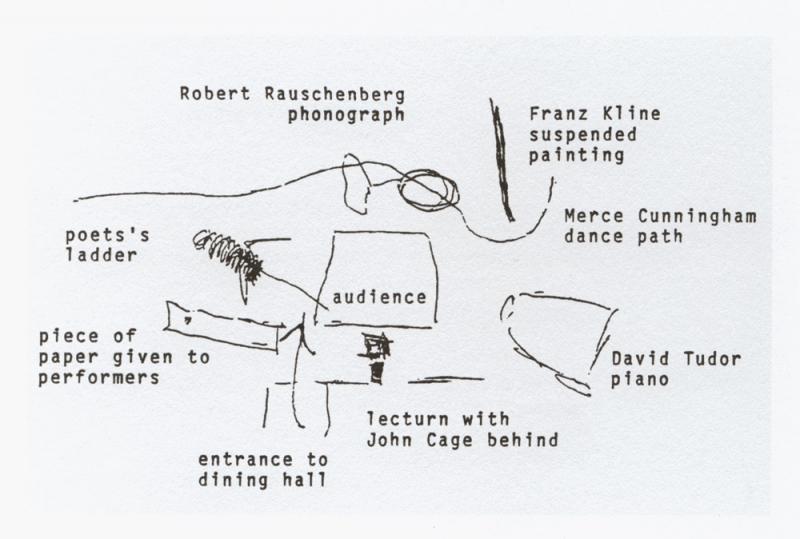

M.C. Richards, floor plan of John Cage’s “Theater Piece No. 1” (1952), drawn for William Fetterman in 1989.

Supposedly and approximately, this is how it happened:

John Cage read from a lecture on Zen Buddhism … as a selection of Robert Rauschenberg’s White Paintings dangled overhead … as Merce Cunningham and possibly a few others danced within and throughout the audience … as a dog, presumably frustrated by a more avant-garde choreography, chased the performers around the room … as Charles Olson and M. C. Richards took turns reading from atop the “poet’s ladder” … as David Tudor struck notes on the piano … as “Edith Pilaf records were played double-speed on a turn-of-the-century machine” … as a movie was shown against the wall. (→ 2)

John Cage directed the event, or Theater Piece No. 1 (as it was later known), during his teaching tenure/pseudo-residency at Black Mountain College, and in keeping with the composer’s distinct style, he compiled it almost entirely by way of chance operation. Performed once and only once in the College’s perpetually make-shift dining hall on an August night during the 1952 summer institute, the event has come to not only represent a critical milestone in Cage’s career but has also emerged as a kind of emblem for the spirit of Black Mountain College itself – a dazzling, albeit confusing, and sometimes difficult-to-parse moment of artistic and life expression.

Black Mountain College has, since its closure, taken on a kind of mythic aspect, much of which can be attributed to how the school has been rendered historically, which is to say quasi-factually. As noted by Mary Emma Harris – one of the first researchers to conduct a full gathering of the Black Mountain story and its materials – beyond the college records that are little more than basic information “such as who was there and when”, the history of the school rests mainly in the “memories of its students and faculty and in their...notes, photographs, correspondence, journals, and other materials”. (→ 3) Often contradictory, never holistic, and sometimes self-poeticised, this wilderness of documents and memories can appear more like a series of palimpsests, where later recollections and uncovered journals efface earlier impressions of what happened and how. As a result, Black Mountain arrives at the modern reader as this layered yet illustrious vision of reminiscence and memory, made even more mythic by its legendary roll call of avant-garde names, all of whom evidence an impossible level of artistic and cultural success. It’s only natural to romanticise, to fill in the loose gaps of its narrative with our own dream.

-

(1) John Cage, “On Film,” April 6, 1956, in John Cage: An Anthology, ed. Richard Kostelanetz (New York: Da Capo, 1991), 115. Quoted in Kay Larson’s Where the Heart Beats: John Cage, Zen Buddhism, and the Inner Life of Artists (New York: Penguin Press, 2012), 255.

-

(2) Several sources chart the event, some a bit differently. For this list of “as,” I selected those things that seem to occur in most people’s account of the event. The actual quotation is selected from Francine du Plessix Gray’s “Black Mountain: The Breaking (Making) of a Writer,” Black Mountain College: Sprouted Seeds: An Anthology of Personal Accounts, ed. Mervin Lane (Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press, 1990), 300.

-

(3) Mary Emma Harris, The Arts at Black Mountain College (Cambridge: The MIT Press, 1987), xvii.

The pioneering Theater Piece No. 1 – being a significant aspect of the College’s story – has followed a similar historical trajectory. Without the benefit of direct evidence or night-of documentation, and without a corroborating through line in the blurry remembrances of competing journal/diary entries, it’s no surprise that this event has become somewhat subsumed by its own myth. And as myth, the piece has become more like a story of art rather than a work unto itself. Of course, several scholars and critics have attempted to coordinate those erratic and fogged-out details into something resembling a single, whole document. This, however, as the attempts can attest, has ended up being a rather unproductive exercise. Yes, the work of arranging details does create a small window into that particular night, but, as Ruth Erickson has noted, perhaps it is better to approach the event from an altogether different angle. As she suggests, “Rather than attempting to pin down what happened...we might take a cue from the improvised event and shift our energy toward tracing the encounters between people, ideas, and art forms that led to the performance on that warm August evening in the rural South”.(→ 4) Although her project was more invested in the encounters that led up to the event, her focus on convergences rather than distinct points is a crucial realignment in thinking about the work. It’s a realignment that not only mirrors the teachings and philosophic underpinnings of the College itself, but one that also reflects the observations of a critical volume of ecosophical praxis: Félix Guattari’s 1989 The Three Ecologies.

At the heart of Guattari’s work is an articulation of a new kind of subject, one whose “interior life” is more akin to a “crossroads where several components of subjectification meet to make up who we think we are”. (→ 5) Generally, what this thinking suggests is that our idea of interiority is actually constructed by exterior forces that pass through and around us, and that the consolidation of ourselves as subjects is only achieved temporarily as multiple components come to reside in the same “terminal”. Thus, the make-up of what we might consider to be our capital-B Being is constantly in a state of flux with the changing and shifting particulars of our environment. By this rendering, there is no definite and rigid individual moving about the Earth. Instead, we are constantly being composed by the particular energies and forces of the Earth. He regarded these forces, or “components of subjectification”, as ecologies, and he articulated them in three distinct registers: the environment (i.e., environmental ecology), social relations (i.e., social ecology), and human subjectivity/perception (i.e., mental ecology). Together, they form what is ultimately an assemblage that may better serve the whole of our subjectivity, which necessarily includes the world. In a way, it’s a rearticulation of consciousness that expands our “existential territory” beyond the preconceived notions of the individual.

-

(4) Ruth Erickson, “Chance Encounters: Theater Piece No. 1 and its Prehistory,” in Leap Before You Look: Black Mountain College, 1933–1957, ed. Helen Molesworth (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2015), 299.

-

(5) From Ian Pindar and Paul Sutton’s “Translators’ Introduction,” in Félix Guattari’s The Three Ecologies, eds. Ian Pindar and Paul Sutton (London: The Athlone Press, 2000), 12.

Art, for Black Mountaineers, was both living and learning. It wasn’t necessarily some final object.

All of this sounds rather abstract and in some ways utopic (Guattari saw his aim as not just a rearticulation of the subject, but also as a recreation of the very world), but there is a sense in which it is both conceivable and feasible. In fact, it’s something that I’d argue has a number of art historical and cultural precedents, most notably in the artistic and communal goings on at Black Mountain College. Seeing as Black Mountain was an arts-centered institution established, in part, on the tenets of John Dewey, its curricula was geared more in the direction of experience as art, which undoubtedly afforded the students and teachers space to possibly pursue different modes of seeing, being, and feeling. By way of an attention to continuous process, participants in the Black Mountain experiment were afforded a vision of the world that didn’t, to use Dewey’s image, simply see the flower. Rather, they were taught to see the flowering. (→ 6) Art, for Black Mountaineers, was both living and learning. It wasn’t necessarily some final object.

-

(6) John Dewey, Art as Experience (New York: Capricorn Books, 1934), 4.

Theater Piece No. 1 was, in its own way, a kind of paradigm of this institutional creed as well as a distinct, vibrant, and historic convergence of Guattari’s ecologies, localised and concretised within a single event. As audience, art, and movement merged into a unique cacophony, what also materialised was the potential for a new kind of social and psychic category, a category in keeping with the greater spirit of the College. This is the story of the event that I find most relevant – as myth, as potential, as a site of becoming. And not just as a study of what the audience that night might have felt or been privileged to (i.e., what they might have felt as themselves), but also as a study in how the piece might be opened, read, and discovered now – how its particular convergence might say something about being here, in our heads today.

Depending on whom you ask, the audience reaction to Theater Piece No. 1 was either one of revelation, boredom, or something in between. As Francine du Plessix Gray recounts, “Most people who sat through it felt that it was great, that it had been an interesting experience and a worthwhile effort on the part of everyone who was taking part.” This, though, is a slightly more positive interpretation of events than, say, David Weinrib’s. As he suggests, “There were a lot people looking at clocks.” (→ 7) Of course, these differences can be chalked up to a number of things. Perhaps it had something to do with where people were sitting. Or perhaps it had something to do with the fact that many of the audience members had already seen these artist-performers do their thing outside of this mash-up, and so seeing the work together did little for them. Or perhaps to the already experimentally minded crowd, the event seemed like something that had already happened in different albeit more engaging ways. Or perhaps people were simply very tired and just wanted to sleep.

-

(7) Both Gray and Weinrib were interviewed by Martin Duberman, and a lengthened version of their accounts can be found in Duberman’s book, Black Mountain: An Exploration in Community (Evanston, IL: Northwestern University Press, 1972), 373–74.

Regardless, the fact remains that people sat through it; that people did experience it. And I might even go so far as to say that they were the performance, or at the very least a major player in it (a claim that certainly holds water when considered in light of Cage’s other works, like 4’ 33”). For the event, the audience was seated in a square bisected by two perpendicular aisles and set directly in the middle of the space as performers, sounds, and images inundated their surroundings. The effect of this arrangement meant that, even if one were somewhat disinterested, one could not go about watching or studying any one thing without hearing, seeing, or sensing the presence of other actions, objects, or images. Now, I’ll pause here to acknowledge that one could describe nearly all of human experience this way: as a subject positioned at the center of their universe with any number of available sensory events circulating their spot. The point here, though, is not to articulate that basic feeling of sitting in any room, but rather to acknowledge the possible effect of artistic interventions on the shape of a psyche sitting in this one particular room. In other words, as much as it could be dismissed as an hour spent looking at clocks, there’s also a way in which the event can be opened up as a site of potentiality, as an occasion for understanding how to look, feel, or be differently. What I mean is that there’s a way in which to look at it where we might say that the attendees that night – situated in the middle of the vibrant maelstrom – may have felt themselves mutated for a moment, drawn away from a sense of self as singular and pushed toward a sense of self as nexus, where distinct currents converged in a greater event of simultaneity. Regarded in this way, one might even say that their role in the piece, as a group and as persons within that group, was to enact and live through the very restructuring of that moment, and through that kind of disorientation, feel themselves within a coalescence, a merging.

Keying in on some of the more Buddhist aspects of Theater Piece No. 1, Kay Larson described the event as follows: “Lacking a narrative, the event has no plot and no denouement. Everybody in this moment is ‘going nowhere’. Each performer’s action, since it doesn’t support a narrative, is clearly a process. Each and every being in all of that time and space is related to every other being – penetrated and being penetrated by all the others…” (→ 8) Larson’s discussion of interpenetration not only affords us one of the better pathways into the event, it also harmonises rather well with Guattari’s ecosophic articulation. In fact, as Gary Genosko has shown, Guattari’s “real innovation”, and thus why he is of particular interest here, “was to develop the relationship between art and ecology through the question of the formation of subjectivity.” (→ 9) Art, for Guattari, was about “opening up processually from a praxis that enables it to be made ‘habitable’ by a human project”. (→ 10) And “eco-art”, as he would qualify it, was, in essence, expressed through this “praxic opening-out”. (→ 11) Beyond the experience of process itself, what’s notable about this articulation is that it engenders a vision of art as a whole greater than its constituent parts, a vision that is in keeping with Cage’s own practice, and, more specifically, his Theater Piece No. 1.

- (8) Larson, Where the Heart Beats, 254.

-

(9) Bernd Herzogenrath discusses the scope of Genosko’s essay “Subjectivity and Art in Guattari’s The Three Ecologies” in “Nature|Geophilosophy|Machinics|Ecosophy,” Deleuze|Guattari & Ecology, ed. Bernd Herzogenrath (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2009), 12.

-

(10) Guattari, The Three Ecologies, 53.

-

(11) Ibid.

Indeed, as White Paintings reverberated the moment back into the space … as the sound of poetry merged with foot patter … as piano notes curled within the space of everyone’s ears … as the likely open windows in the dining hall introduced night sounds into the folds of Cage’s voice … as all of this was going on, a sort of multivalent architecture was being built, an architecture assembled through a performance of simultaneity where the participants in the room, situated in the space’s center, held in them an opportunity to interpenetrate in and within this collected state of “happening”, to inhabit this moment of opening-up. And as long as they were willing to participate in the processes of this kind of artistic making, or perhaps more simply be a witness to the performance of something entirely new, they might have been able to install themselves there and participate in a new way of living through art, a way that occupies its own space of assemblage – a whole for everyone to emerge in, a living theater.

“In Theater Piece #1, no one could tell where the ‘artwork’ ended and the ‘world’ began … liberated from the need to pick and choose to fit a theme or interpretation, artists discovered that art could embody the processes of living in each moment”. (→ 12) What better way to describe an art of living? To say that we are roaming nodes of potential, each engaged in the process of life, in the making of life? I keep on coming back to this as a succinct impression of what this piece, and by extension the College, might mean for the world. Even as Black Mountain’s history is interpreted and abstracted to the point of romance or myth, what remains true is the fact of its architecture, and by that I mean the space it has created (and continues to create) for the purposes of our own “human project”. When I look back through the school, and when I look back to the hour Cage invented that night, I think about them not just as moments in history but as habitats for a present awakening, a beacon for an altogether different path forward.

- (12) Larson, Where the Heart Beats, 255.

Tyler Laminack is a writer and performer living in Chicago, IL, where he works as a publications editor at the Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago. His MA thesis "A New Art of Living: The Three Ecologies of Black Mountain College" (Faculty of the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences of Georgetown University, Washington, DC, USA, 2016) is availlable here (accessed March, 2021).

Declared the first happening, the performance (referred to by many as “The Event”) took place in August 1952 at Black Mountain College. Later named “Theater Piece No. 1”, it was one of John Cage's first large scale collaborative, multimedia performances, created and performed while he was teaching at Black Mountain College in North Carolina. It involved several simultaneous performance components – all orchestrated by Cage – and chance played a determining role.

“maat Explorations” is an ongoing programme that delves into the socio-cultural and environmental transformations stemming from the current bio crisis and ecological destruction. It provides an insight into the hard science of climate intervention and the creative speculations behind innovation-led research to safeguard our planetary co-existence.

Prominent in this strand is the installation Earth Bits – Sensing the Planetary, that opens access to the complex interconnectedness between the environmental and the energetic quests and its reverberation through decades of artistic production, political and cultural movements traced from the 1960s until today.

On maat ext., a series of #groundworks hashtags introduce the critical explorations that feed into the complex interconnectivity between the environmental and energetic quests, and its reverberation through decades of artistic production, political and cultural movements traced from the 1960s until today.