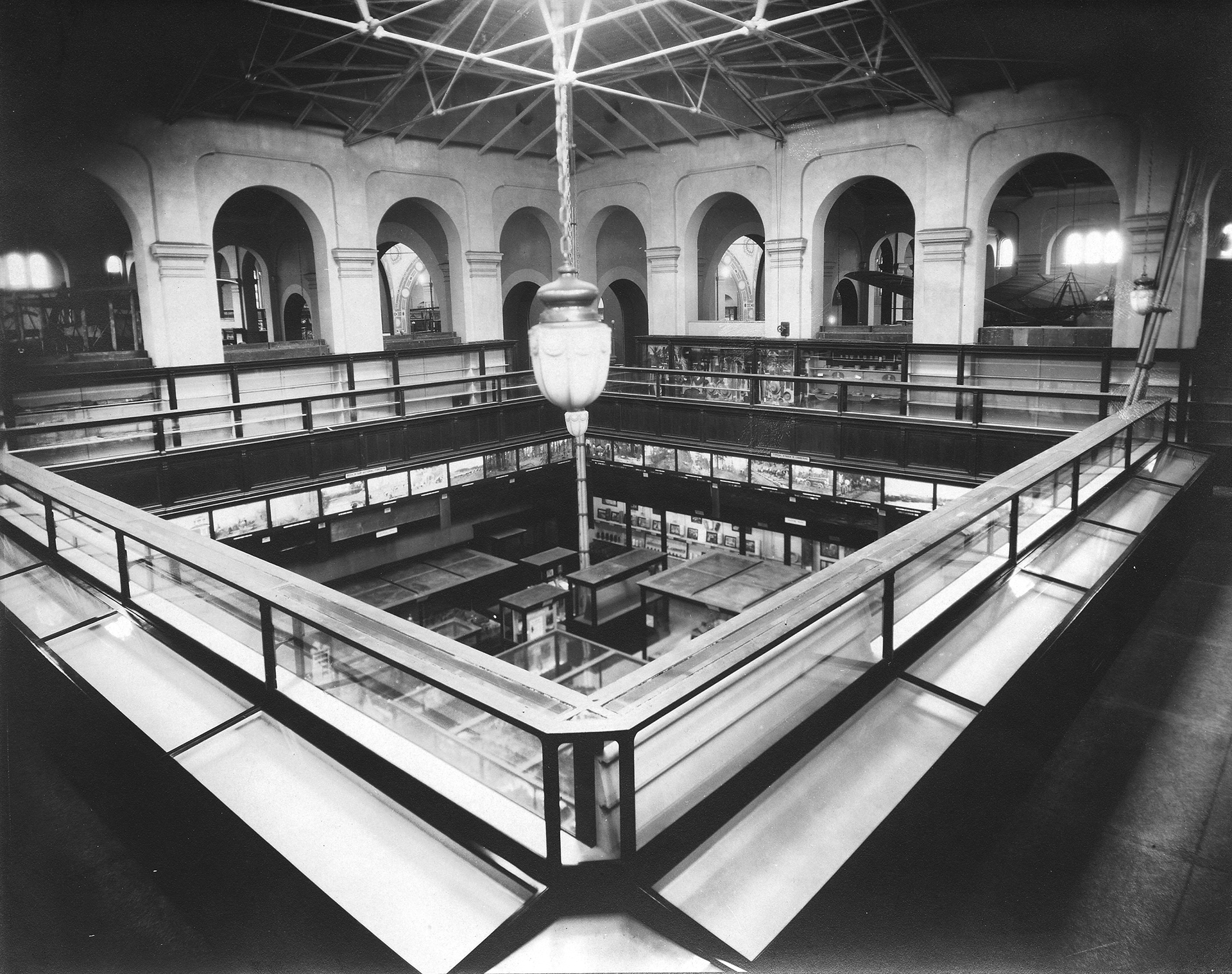

Empty exhibit cases at the United States National Museum, now known as the Arts and Industries Building, 1880s, USA. © Smithsonian Institution Archives. Image # SIA2002-12210.

In this aphoristic mini-essay, I want to think in broad terms about the aestheticisation of poverty within the category of the other. I am writing as a person who among many things is a cultural mediator and tries to produce thought about two subjects that complement each other: the museum as a gentrification device and the aestheticisation of the other, of other bodies, by the so called social/participatory art/architecture.

These aphorisms are also born of a separate desire to understand how visual culture, and above all contemporary art, builds and manipulates the other’s appearance, of one another, as art’s aesthetic category, which is capitalised.

Initially, I had decided to write about poverty but while I was reflecting I felt it was necessary to understand the act of seeing, in order to then understand and dismantle how the other is seen and built through artistic objects, which is to say, the intention of the theme is set on the subterranean basis of the text, which served as a motto to start the structuring and questioning of “seeing is subject” (by Georges Didi-Huberman*).

1. |

There is no autonomy in art, we are all “seeing is subject.” To think about universality, or even an essentiality of seeing, it is necessary to consider this premise: that the construction of its category (conceptual) in the establishment of the aesthetic experience is always just a prop of normative culture that gravitates within its own centre and that, like the blind spot in a car, holds hostage to all that doesn’t fit in its field of vision.

2. |

We are not neutral, what we see and how we integrate the categories of perception in our cognitive structure has influence on the construction of otherness and its imagery. Let us see how, in the beginning of the 1970s, this was questioned through the deconstruction of the hegemonic gaze by John Berger in Ways of Seeing (1972), calling to our attention the fact that the active element of seeing is in the masculine subject, normative, that has created visual devices tailored to his needs; then Laura Mulvey demonstrated that in her essays about the construction of female imagery through and within cinema; and more recently The Oppositional Gaze: Black Female Spectators (1997) by bell hooks, or in the documentary films: Disclosure: Trans Lives on Screen (2019) by Sam Fader and Exterminate All the Brutes (2021) by Raoul Peck, transforming Berger’s emblematic quote, “men act and women appear” into “the centre acts and the suburb/periphery appears.”

3. |

That observer, as specific as we are, is an engaged subject that observes, that is not isolated from influences and power relationships produced by imagery through the gaze of the politics of perception, deciding which images we have access to, and how.

4. |

This is “seeing is subject.” As Didi-Huberman observes: there is no neutral gaze. The utopia of the minimalists would never succeed, because the observer is herself or himself a subject made of several layers of discourse, symbolic and psychological. To analyse and interact with objects, whether they are physical or of thought, is never a linear act, fixed and crystalised in time as well as space.

We can say that it is actually a dialectic process that with fluidity intersects the various layers of sensitive and sensory apprehension, which sometimes shows and other times erases. This game between presenting and disconnecting also involves the representation of the other, mostly integrated in a methodology of Cartesian nature, making the observer external and dissociated from the experience of otherness. In other words, this representation is free of the tensions and conflicts inherent to difference, misleadingly turning into immutable and atemporal spaces.

5. |

Let’s take as an example “public” statues, that don’t truly represent a universal “body,” but rather normalise the way we see, for example, a colonial world, making it an ideal to be followed, bursting through the collective imaginary as global, which is to say, this seeing that is subject unconsciously absorbs the dominant narrative of this “glorious” history, and this is why it makes sense to ask the question about the re-signification of hegemonic imagery.

6. |

The analysis of the aesthetic experience has to take into consideration the positioning, the location of the bodies, what this positioning carries. It is impossible not to take gender, race and class into consideration.

The perception of the museum only takes into account a generic user who influences the sensory and aesthetic experience of that space. There is a gaze that formats and hegemonises, disregarding the full access of other bodies. The seeing-around-you of the “seeing is subject,” starts with a positioned body, located, as stated by Adrienne Rich.

7. |

That body is not merely a set of organic elements, such as arms, legs or a head. We are not only citizens, our body is also constituted by our gender, race, sexuality and social class. It is from this configuration that we look at reality and construct it, always starting with our body, and consequently forming spaces.

8. |

The “seeing is subject” is positioned geographically, historically, culturally and politically. All our dimensions influence the way we build ourselves, and how we build the relationship with the other through spacing processes. This body is not merely an element of the eye, which causes a vision devoid of the subject, with no experience. Seeing here is understood, as mentioned before, not on the plane of projections that appears or manifests itself anticipating schemes that give meaning, or appear to the seeing, but rather as a seeing that starts from one's own experiences of their body, of their living, of their subjectivity, breaking with the generalisation/universality of perception.

9. |

This awareness, as we have seen, is not peaceful, there are several layers, tensions and dissensions in the apprehension and making of alterity. The other can be taken as something or someone whose undefined reference lies outside the sphere of speaker and listener, and which is implicitly or explicitly opposed to something or someone defined, known. It is also through a positioned body that we become aware of reality and all that is around us, and that we simultaneously become subjects and objects, discovering the otherness that is in us.

10. |

Modernity has shown us that that subject that sees, is not an element that merely contemplates, and that the object is not simply an object devoid of intentions, but rather is made by the standardised layer of society, taking Hegel's idea of master and slave; what we have had until today is a standardisation of the other, a suppressing of the other through agglutination, homogenising the horizons of meaning, eliminating the other, reaching the point where we are in a culture of recreation of what we have repressed. When one stifles a culture and its artefacts, we have to recreate what is different and by recreating it, we are before a false equivalent made in the image of the creator, the hegemonic.

11. |

Our interventions, whether as active or passive subjects, are not redrawn from the various layers that constitute reality, even if their intention might be so: “seeing is subject,” a subject that is not devoid of ideology, symbology and pre-conceived ideas, therefore apprehending and conceiving objects, is never an objective, a fixed and rigid act, but rather a fluid dialectical process of intersections, which in the context of the materialisation of a hegemonic narrative within visual culture erases people that are “subalternised.”

12. |

If “seeing is subject,” then the “seeing” of the subaltern subject also carries on its shoulders the scars of the making of their subjectivity which is imperative to include. In the various social empowerment movements, we see that there is a difficult resistance of the privileged subject, who challenges us, in an attempt to maintain the established narrative by devaluing the experience of the other; “seeing” thus becomes a political act, an active act that wants to gain space and activate projection, becoming agitated. And it is through this restlessness that you wish for the subject that is being awaken from their dogmatic dream, that they become aware that the elements that are part of a city, whether it’s global or local, are not neutral; that “public space” and how it builds its alterity, in a colonial, patriarchal and patrimonial system, is only a simulacrum. A space that is hierarchical, administrative and homogenised, isn’t truly public as it doesn’t represent the whole, in a sum of its individualities.

13. |

This “seeing is subject” has a body that problematises its location (Adrienne Rich). Its spacing is not devoid of identity, and, with that, the conceptual analyses of that layer allow other ontologies to coexist outside of a process of hierarchisation and abstraction, sending the observer into a mere container, as a passive and acritical builder when it comes to taking up space, incapable of living and critically analysing the space.

14. |

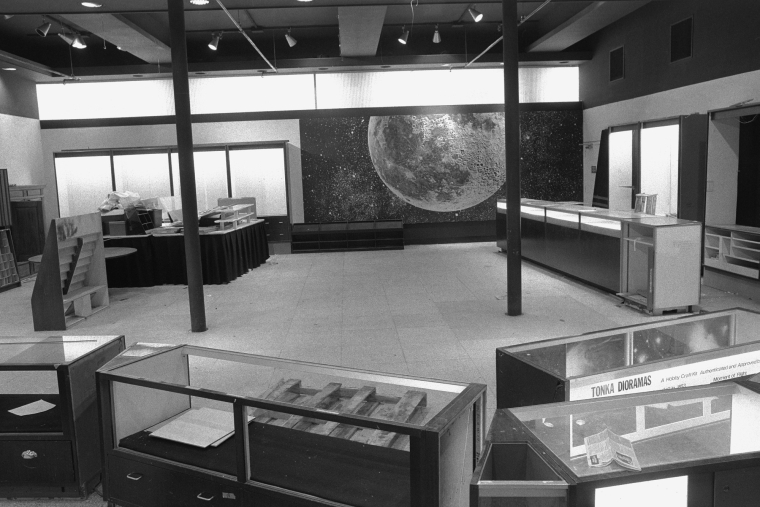

The museum as a device for seeing is not neutral; what is its location (A. Rich)? The seeing is the subject of the museum, as put by Paul B. Preciado and Achille Mbembe; it is a segregation box that only welcomes through a one way street, a “necro-museum” where the discordant public space has died at the hands of entrepreneurial neoliberal art. It is difficult to enter the world of art and contemporary visual culture and not come across a web of intersections of meditative and media devices that do not capitalise and romanticise poor and marginalised communities, without even belonging to those communities. These spaces have become segregating boxes responsible for the construction of alterity, of a marginalised other that art has to save.

15. |

It is through a (synesthetic) body that we become aware of the world and that, simultaneously, we become subjects and objects, discovering the alterity within us. For example, Marie-José Mondzain in her book Homo Spectator says: “the caveman produces his horizon and gives birth to himself by extending his hand towards an alterity that is unyielding and vivifying, his own.” This is how the spectator is born: through the simple gesture of reproducing his hand on the walls of the cave; in this gesture of pure duplication, he sees himself for the first time as an object, with which they begin to alternate, with the conception of himself as subject.

16. |

How can then we comprehend the dissolution of the other in contemporary times? Where is their awareness and knowledge, as well as the opacity and the unexpected, similar to an expression of freedom? The questioning of the other is not new, this has always been an issue; what distinguishes it today is the emancipation of the other, which is to say, the relationship many times imposed between the self and what is strange, between the hegemonic subject and the subaltern. For Byung-Chul Han, our contemporary times no longer have the category of the “other,” but of the identical, and this leads to acts of violence, in order to dilute this “other” that no longer exists. On the other hand, the other struggles to avoid becoming an undifferentiated mass, a mere thing.

17. |

Where do we locate ourselves when working poverty? From which located body? The term “poverty porn” refers to works and artists who capitalise and romanticise, organising poor and marginalised communities without even belonging to them. The art market wants poverty, but it doesn’t want it when it comes with its own place of speech.

18. |

The issues raised here have to do with the concept of superfluous people explored by Bauman, which corresponds to those who are on the margins, as opposed to the standardised layer of society.

And the art of “poverty porn” can be understood through this prism, of another superfluous thing that is part of the standardised layer of society. Taking Hegel's dialectic of master and slave, what we have today is a standardisation of the other, a suppression of the other through agglutination, homogenising the horizons of meaning, eliminating the other, to the point where we are in a culture of recreation, of what has been repressed. When a culture and the artefacts it created are suffocated, we have to recreate the definition of difference, and in recreating it we are faced with a false other, created in the image of the creator, hegemonic. Are participatory objects not victims of this systemic way of seeing the other?

19. |

Will the dissolution of the other occur through submission or through the emergence of new modes of oppression, generated in silence or hidden in plain sight? And how can one challenge an oppressive force within the cacophony of discourses, where all sonority is lost as well as the invisibility of a plural whole, where group identity seems to be lost along with its homogenisation? Maybe a new voluntary servitude has been established? A servitude to a faceless master, where the position of conflict, the play of forces between the self and the other has been lost in the making of the image?

* |

“To see is always to disquiet the seeing, in its act, in its subject. To see is always an operation of the subject [...]. Binary thoughts, the thoughts of the dilemma are therefore inadequate to apprehend anything of the visual economy as such.” Georges Didi-Huberman, (Portuguese translation, O que vemos, o que nos olha, Dafne Editora, 2011, pp. 57-58).

Maribel Mendes Sobreira is an architect, curator and researcher, a PhD student in Philosophy at the School of Arts and Humanities (Faculdade de Letras) of the University of Lisbon (FLUL) in Aesthetics and Philosophy of Art, and she was an FCT (Foundation for Science and Technology) grant holder from 2016 to 2020. She holds a Master's degree in Philosophy from FLUL, she is also a PhD student in Philosophy at FLUL in the field of Aesthetics and Philosophy of Art, and was an FCT scholarship holder from 2016 to 2020. Sobreira is a member of the Philosophy Centre of the University of Lisbon (CFUL) and of ISPA (International Society for the Philosophy of Architecture). She designs and runs activities to raise awareness of the arts and architecture, collaborating with Museu Coleção Berardo and maat at that level. She started her curatorial practice in 2019, with the project ARQUIVO EXQUIS, in Lisbon, and she co-founded ColectivoFACA – a curatorship and active citizenship project that questions the narratives of visual culture, not erasing history and intersecting the various narratives. She has published articles on architecture, urban heritage and art theory, noting, in particular: “Relation of Architecture and Philosophy in the tragedy of culture” (2018) and “Time of the shapeless” (2020).

“Empty Exhibit Cases” gathers three cisgender white women working in the arts, Susana Pomba, Susana Gaudêncio and Maribel Mendes Sobreira, on their way to become life-long anti-racist and effective allies, as artists, teachers, researchers, curators, historians, writers, or authors. The project delivers a group of essays (in diary mode), that might be hybrid in form, and attempt to dissect various questions and struggles, all in the context of the daily personal and professional lives of the three participants. They will also engage in conversation with activist groups, scholars, or cultural agents.

Based on diary-keeping as a form of writing, the Mode Diaries initiative creates a field of interpretative potentialities within the context of maat Mode 2020, a public, experimental and participatory exhibition and activity programme under the motto “Prototyping the museum”. This is the scope that justifies and enables the twisting of the meaning commonly attributed to the term “diary” by transforming what’s individualised into collective, private into public, singular into plural, etc.