Public Journal Entry

[wa-wa-walking]

An essay in three parts by Susana Pomba for the Empty Exhibit Cases project

|

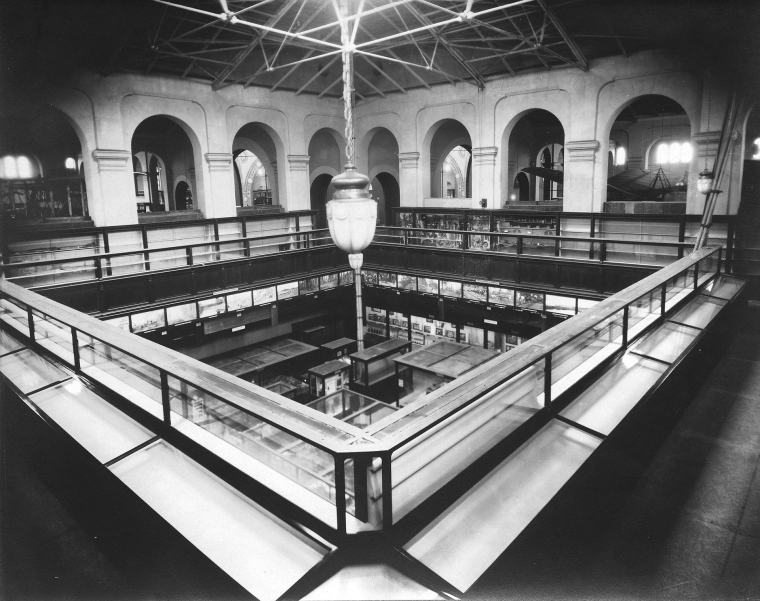

Two photographs: (top) Four mannequins in Japanese costumes in exhibit case; (bottom, upside down) Empty exhibit case in the United States National Museum, now known as the Arts and Industries Building. 1880 © Smithsonian Institution Archives. Image # MNH 3491 |

|

[I would leave the house, cross Maryland Avenue NE and in less than one minute I would turn left, pass the Atlas Theatre, reach H Street, and that was my straight line. 13th, 12th, 11th… the countdown of street numbers would mark the tempo. Part of this organised grid was decided in 1901. North and South streets would continue being numbered, east and west streets would be named after famous Americans, others would have a “single street-name system”, one-syllable names in alphabetical order, then two syllables, then three. Letters and numbers, cardinal directions, seemed to me like an administrative decision, the temporary nomination before the actual name. In my hometown, most streets have religious or cultural denominations, many times the names of prominent men as a way to honour them. With some historical exceptions a name that with the passing of time becomes detached from the actual person, now long gone, and becomes part of the combination of words you memorise to get around the city and give directions, and also there, it seems, all in all, just to make it harder to fill in official forms.]

⩬

PART I

Public Journal Entry

[What a Woman Ought to Know]

“I think often and deeply about women and work, about what it means to have the luxury of time – time spent collecting one’s thoughts, time to work undisturbed. This time is space for contemplation and reverie, it enhances our capacity to create (…)”

— "Women Artists: The Creative Process”, bell hooks (1995)

“The pilgrimage is one of the basic modes of walking, walking in search of something intangible (…)”

— Wanderlust: A History of Walking, Rebecca Solnit (2000)

Hello, it’s me, a woman writing, a white woman writing, a white woman working in the arts writing, a white woman working in the arts in Lisbon, Portugal, Europe, the Northern Hemisphere, writing. This repetitive jovial sentence echoes the beginning of “Notes toward a Politics of Location” (1984) by Adrienne Rich. I thought it would never pass one of my many final edits, but these first words serve as an important disclaimer. Dear reader, these words tell you, my gender, my race, my work, my location, so I don’t assume I represent some sort of universal, default, prevailing culture. Historically, my gender, mistreated; my country, a coloniser; my race, an oppressor. I have lived all my life in the city of Lisbon, conditioned by my education, language, the monuments and symbols that surround me, all impregnated by a colonial past, not studied enough, muffled, unspoken, unresolved. We, the Portuguese, a small (poor) country “in development”, with a recent democracy, after more than forty years of a fascist regime, would continue to study our old grand “discoveries”, and muffle our devastating colonial past (we were not the worst ones, I have frequently heard). Some years ago, I expanded my studies and embarked on a different journey, one that would engage with this past.

A sharp straight line, filled with little blue dots on the digital map, 2.5 miles, or I would rather say four kilometres because it clearly sounds more substantial. Around fifty minutes, only stopping when absolutely necessary as a pedestrian. This I knew, even before I got on the plane to cross the Atlantic. It was feasible, I could walk from the room I had rented, to the library at the National Museum of Women in the Arts. That sharp straight line had a name: H Street NE. Good exercise every day, an easy way to understand the city, and even though the room was expensive for my meagre budget, I would spend a lot less money on transport. That was my reasoning. Walking is still free and I had time. In total, I spent five months in Washington DC with a Gulbenkian research grant, walking alone to every museum, library, free cultural activity, bookshop, to keep my mind and feet in harmony, thinking, learning, living. All to maintain sanity and to make me a better human. The research grant didn’t quite include those objectives, “just” the widening of my scope as a curator when it comes to issues of gender, race, and class. I knew I had to do substantial work. And so, I walked the line. In the first month my daily average was 8,804 steps. In the last month it went up to 12,389.

I am aware that walking and travelling are common metaphors. I thought about this while in DC, how trite to engage in this activity, the journey on foot as the producer of reflection and thought, a physical effort that ignites a life stretched to higher cerebral grounds, to a higher reason. I felt grandeur with each swoop, each boot forward. It is unavoidable, this walking metaphor, our muscles harden, our noggins enlarge. With another boot forward, I kick centuries and centuries of history. I might just trot. There is no point in running from certain grand metaphors. Nautical ones, for instance, are all around us. It might be that I am Portuguese and live surrounded by the Atlantic and an overwhelming history of sea “conquests” and atrocities such as the Transatlantic slave trade, but maybe they are there as an enriched language to be used, as the colour blue in liquid form, taking over you (search for the artist Helena Almeida). So, welcome the metaphor, don’t run, come on board, let’s get on the same wavelength, let’s not rock the boat, just walk the plank, step by step, and dive in, disarmed. Are your arms tied or are they free to swim? Can you stay afloat? They always win, the grand metaphors.

Pilgrimage, endurance, challenge, mental and physical necessity. For a short period at the end of the 19th century, walking was an endurance sport in some Western world capitals. During the 1870s and 1880s, events with food and music were organised to watch people walk. The feat! I came across this in an article by Ashawnta Jackson about pedestriennes: women who walked that “plank” and showed incredible strength and resilience. Women weren’t seen as athletes, or as capable of doing physical exercise. They were only allowed to walk with a specific purpose, like shopping. And no walking was allowed at night, your reputation would be at stake, and you could be arrested. Pedestriennes (a derogatory term at the time) showed endurance and walked for miles, and performed “feats like ‘walking the plank,’ which involved long-distance walks on small wooden surfaces”, writes Jackson, also mentioning Ada Anderson, one of the better known athletes, that in 1878 made a “month-long walk in on a specially constructed ‘three-foot-wide tan bark walking oval’ in Brooklyn”. A few white women did this, but next to no women of colour, who worked more often as attendants for the athletes.

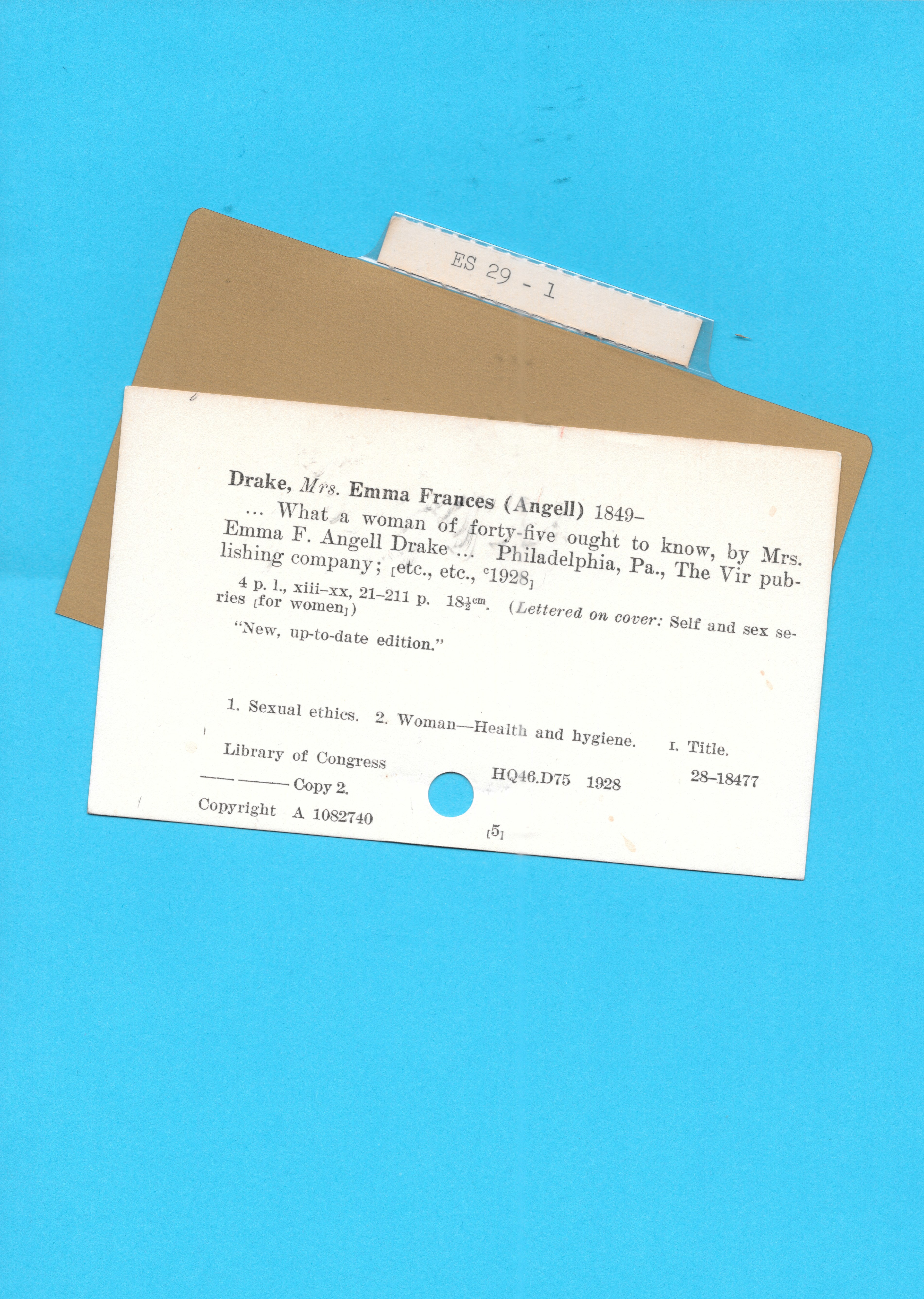

So, here I was in my forties, with a grant and a luxury. I left any hassle or disappointment to be dealt with across the ocean when I got back home at a later date. On the American side of the Atlantic, I had to honour the luxury of time to read and learn. One of the events I went to in DC was a visit to the Library of Congress at night, a special display of old books and periodicals on tables, free of copyright and free to browse and photograph. There were small cards on the table that I soon learned I could use to take notes and then take-them-with-me. The hyphens are used here to give emphasis to the next sentence. They were not blank cards, but actual old library cards, typed on one side, the ones people used to flick through when trying to find a specific book, edition or publication. Cards in wooden drawers alphabetically ordered, now no longer in use. I couldn’t believe I got to take such memorabilia home. Right now, in front of me in Lisbon, I have a small stack of old library cards from the biggest library on earth (the British Library might dispute this fact, based on the number of “items” they might hold, at least at the time of writing).

Referring to interests, issues, subjects, I have heard people say: “I didn’t find it, it found me”. Well, it didn’t. It was me, I randomly found a library card that read: “Drake, Mrs. Emma Frances (Angell) 1849– . . . What a woman of forty-five ought to know, (. . .) . . . Philadelphia, Pa., The Vir publishing company; [etc., etc., c1928]”. Being forty-five years old at the time and a woman . . . I thought, “Was this a sign?” Again, no, but it dovetails nicely with two other essays that really did help me make sense of this search, of what I “ought to know” (are you listening “young lady”?).

This book and its contents described a miserable life after forty-five: plenty about “climacteric”, the “three periods of a woman’s life” (maybe “moments” would have been a better word), ailments, diseases, “a word to single women”, or the “at sea” section for mothers “drifting”, to “self-induced diseases,” which included “diseases induced by dancing in early life” (I might have a lot of those), to exercise that in the 1920s included the “value of walking as exercise and recreation” (I fear recreation didn’t include dancing).

Photo of library cards over blue background taken by the author.

So, what did I really need to know? First, that it is essential to reread the last sentence of Adrienne Rich’s 1979 commencement speech, given at Smith College, a woman’s college in Massachusetts, and titled “What Does a Woman Need To Know?”: “Get all the knowledge and skill you can in whatever professions you enter; but remember that most of your education must be self-education, in learning the things women need to know and in calling up the voices we need to hear within ourselves.” I think of those women in 1979, sitting down in their graduation attire, hearing Rich, a white woman poet, essayist and feminist, and one that wrote extensively about racism: “For women, all privilege is relative. Some of you were not born with class or skin colour privilege; but you all have the privilege of education, even if it is an education which has largely denied you knowledge of yourselves as women”. What a voice to have within you, what questions to tackle. Let her speak some more while we rise from our chairs and are driven by answers in the form of questions: “What does a woman need to know to become a self-conscious, self-defining human being? Doesn’t she need a knowledge of her own history, of her much-politicized female body, of the creative genius of women of the past – the skills and crafts and techniques and visions possessed by women in other times and cultures, and how they have been rendered anonymous, censored, interrupted, devalued?”

Find it, it is all there. One woman will take you to another. Start here: if you read Grada Kilomba, she will take you to bell hooks, if you read Audre Lorde, she will take you to Adrienne Rich, if you read Djamila Ribeiro, she will take you to Grada Kilomba, if you read Lilian Thuram, he will take you to Reni Eddo-Lodge, if you read Françoise Vergès, she will take you to Audre Lorde, if you read Adrienne Rich, she will take you to the Combahee River Collective and back again. I started with the black American feminists, and reached contemporary times with the French decolonial essayists, and the black Brazilian feminist powerhouses. From the Northern Hemisphere to the Global South. And I still have a lot to discover. As a white woman in the arts, there is no need to ask an artist of colour for anything, it is all available to be read. There have been many women of colour that have written it down for you, just self-educate yourself, take Rich’s last sentence for life.

An example of what you might find while reading Adrienne Rich’s commencement speech is that you are, or were, a white woman, at some point in your life, a token woman, let us listen: “the false power which masculine society offers to a few women, on condition that they use it to maintain things as they are, and that they essentially ‘think like men.’ This is the meaning of female tokenism: that power withheld from the vast majority of women is offered to a few, so that it appears that any ‘truly qualified’ woman can gain access to leadership, recognition, and reward; hence, that justice based on merit actually prevails”.

So, what a woman of forty-five ought to know, is that the question really is, what does a white woman need to know? Read and study, you might find out you are a white feminist perpetuating the invisibility of women of colour. You might find that you are a token woman, you might find that with your reluctance in studying these matters, you are silencing women less fortunate than you. We will have to do it all at the same time, questions of gender, race, class and all the intersections, and you will find there is no better way to understand these relationships than imagining the experience and reality of black women, the most oppressed, the most invisible. A point made by Keeanga-Yamahtta Taylor in her article in the New Yorker about the Combahee River Collective, titled “Until Black Women Are Free, None of Us Will Be Free”, a point made by many black women writers.

Imagine it. Grace Paley said it in 1986: “(…) men have got to imagine the lives of women, of all kinds of women. Of their daughters, of their own daughters, and of the lives that their daughters lead. White people have to imagine the reality, not the invention but the reality, of the lives of people of colour. Imagine it, imagine that reality, and understand it”. “Of Poetry and Women and the World” was the name of the talk where she uttered this sentence which at the same time may function as a conclusion and also as a start.

Read and study, you might find out you are a white feminist perpetuating the invisibility of women of colour.

|

An example of the H Street heritage trail, this one on 11th street featuring a photograph of the Douglas Memorial Church in 1967. Photograph by the author.

|

|

[Early on I noticed the Greater H Street NE Heritage Trail, and the words, “Hub, Home, Heart”. The first sign I saw was number 16 (7th street) and it stopped me in my tracks. First sentence: “On Friday, April 5th, 1968, the 600 block of H street went up in flames. The Reverend Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., had been assassinated a day earlier, and grief-stricken, angry men and women had taken to the streets across the city, looting and burning.”

I also noticed around 11th street, a red brick church, the Douglas Memorial Church. Since 1878, it has gone through a name change, white flight and then finally in the second half of the 20th century it was established as an African American church. Today, as H Street itself, it is going through gentrification. There was one evening, while passing through that I saw a small spontaneous memorial filled with flowers and candles, on the ground in front of the church. The candles were lit, fresh. There were pictures.]

≃

PART II

Public Journal Entry

[The Invisible Role-Models]

“As far back as slavery, white people established a social hierarchy based on race and sex that ranked white men first, white women second, though sometimes equal to black men, who are ranked third, and black women last.”

— Ain't I a Woman: Black Women and Feminism, bell hooks (1981)

While walking, street corners are not read as sharp edges, we don’t make swift 45-degree turns as if we were somewhat mechanical, or working for the Ministry of Silly Walks. We zig-zag, we curve, we dodge trash bins, bus stops, shop signs and other people. One evening in DC, I walked for about an hour around the same square. I don’t think I was driven by wanting to exercise but by a desire to find something or someone. I was walking in circles, marking each bus station, each empty bench, noting the green rugged area in the middle. A walk begging to be interrupted. Later, I connected this to the time I first left the house without a clear destiny as a young girl. I think I was twelve and had a tantrum. I walked around my neighbourhood alone and with no clear end, a new feeling. Where should I turn? Where should I choose to go? I was scared about the whole independent solitary impulsive walk, but dove in. Never walked back since.

I have filled my life with exhibitions, not necessarily with contemporary art (even though most are). A few of these exhibitions have been life changing. In 2019, I saw in Paris Black Models: From Géricault to Matisse at the Musée d’Orsay, an extended version of researcher and curator Denise Murrell’s thesis, “Posing Modernity: The Black Model from Manet and Matisse to Today”, that with this same title had a first version at the Wallach Art Gallery at Columbia University in New York. The painting that started it all for Murrell was Manet’s Olympia or the fact that early in her studies in a class a lecturer spoke nothing of the black maid holding the flowers, rendering her completely invisible. No mention. From that moment on, Murrell embarked on a series of studies of black women figures in painting, all because of Laure, Manet’s model for Olympia.

The exhibition at Musée d’Orsay was groundbreaking, it gave a name to many of the models in the sculptures and paintings exhibited. Gave them a name by changing the titles of some of the works in the exhibition. Yes, that is possible, history and art history can be corrected. There was extensive research, made by curators and historians, on the biographies of black models that appeared in the art of the 19th and 20th centuries. An example is Marie-Guillemine Benoist’s portrait that opens the exhibition: originally called Portrait of a Negress, it was later renamed Portrait of a Black Woman and now for this exhibition it was titled, Portrait of Madeleine (1800). That was her name, she was from Haiti, a former enslaved person that was freed.

Complementing the show there was also a new work by American artist Glen Ligon called Des Parisiens Noirs, which consisted of 12 neon names divided by two panels in the great Gare d’Orsay. We can read “Madeleine”, “Alexandre Dumas”, “Laure” and other names, some with only a first name, some with surnames. Should some be names of streets? Laure appeared in one of Manet’s notebooks as “Laure très belle négresse 11 rue de Vintimille 3e”.

Anonyme, L’atelier de Lucien Simon avec étudiants et modèle noir féminin, à l’École des beaux-arts ou à l’académie de la Grande-Chaumière, vers 1930, contretype moderne, Paris, Association Lucien Simon

|

Lucien Simon's atelier. Image altered by the author. |

The above caption belongs to an image also present in the exhibition. I took the liberty of painting over a part of the photograph. I am thinking of artist, curator and educator Deborah Willis’ words, “dress as armour”, when thinking how black women used clothes as battle gear when demonstrating or just taking their children to school in 1960s segregated America. What we see is a group picture, probably taken at the end of a live model drawing class. There are some paintings in the background. There are a lot of students sitting down, others found ways to elevate themselves to fit the photograph. There are many men, but also many women. Most of them are white, but an Asian man and woman are also amongst the students. Many have soft or full smiles on their faces. I deduce they organised themselves around their professor, an old white man. The model, a black woman, is also there. Amidst a sea of fully clothed humans she remained completely naked for the picture. No one gave her a robe, or her own clothes. No one thought this was wrong. Such violence and lack of basic respect, all tangled in one picture. “That was back then,” white people say as a sentence they repeat because they hear other white people say it as a justification. “History is literally present in all that we do”, said James Baldwin. We carry that history today. What was her name?

When I was in art school I attended many of these types of drawing classes. There were no black models—our colonial past was not “past”, it was conveniently hidden, as if it didn’t exist, unspoken, thrown to the side, to the outskirts, the margins. But it was all there. It was the 1990s, and I remember one of the teachers making remarks on the white woman model, something misogynistic I cannot remember. He also made remarks on what I had just painted, he was the teacher after all. He pointed at the nose and said it was not good (as in not similar to the model’s nose in front of us), he said it “looked like a black nose” (he meant it disparagingly). Even then, in my white girl ignorance, I flinched.

Yes, that is possible, history and art history can be corrected.

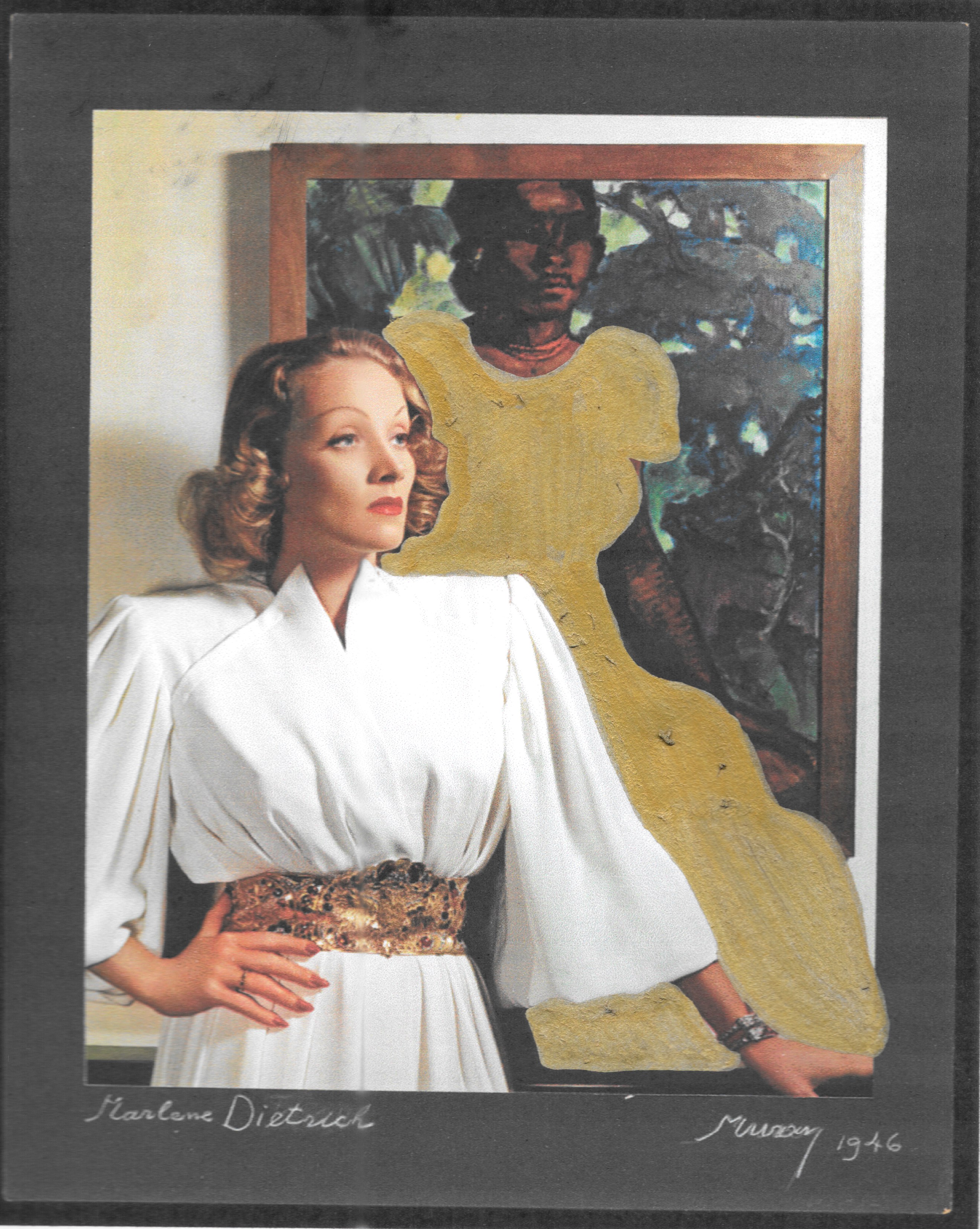

A Nickolas Muray 3-colour carbro portrait of actress Marlene Dietrich. Dietrich is in front of a Paul Gauguin painting in a white dress with ornate golden belt. She is striking a similar pose as the native subject of Gauguin's painting.

Paul Gauguin made a copy of Manet’s Olympia in 1891, to study it, probably in preparation for his own “Olympia”, the well-known painting The Spirit of the Dead Watches (1892), depicting Teha'amana, a Tahitian that was 13 when she met Gauguin (and not much later married him). This copy was also presented in the Musée d’Orsay’s exhibition, alongside many other Olympia variations. This might be a good segue to tell you about a photograph I found online of actor Marlene Dietrich in front of a Gauguin painting. This portrait belongs to the Smithsonian collection, and was taken by Nickolas Muray, a Hungarian-American photographer known for his colourful portraits and connection to artist Frida Kahlo. Here, the white woman stands dressed in a white glamorous gown in front of the painting of a naked woman of colour. We know the name of the famous white woman born in Berlin, known not only for her films but for being politically vocal against the Nazis, and defying conventions when it comes to what women are suppose to wear. In her case and in her time, suits and trousers, or should we say male clothes, “unsuitable” for women. I tried to find out who was the model in Gauguin’s painting. But I didn’t even find evidence of this painting actually being by Gauguin, as I couldn’t find it in the catalogue raisonné of his paintings or in any of the books I carefully browsed. So, maybe this isn’t a Gauguin painting after all, but one à la manière of the famous painter. Revising Gaugin’s legacy today is divisive. Problems concerning the age of his subjects (I prefer not to use the word muse, it implies stillness and being in service of the master) and the way he colonised them. Still, Gauguin remains an interesting subject himself, as historian Norma Broude’s book Gauguin’s Challenge argues. The chapter “Flora Tristan’s Grandson: Reconsidering the Feminist Critique of Paul Gauguin” reveals a little known fact to the general public: Gauguin was the grandson of Flora Tristan, a 19th century socialist and activist writer who made a substantial contribution to the development of feminist theory and women’s rights. Gauguin never met his grandmother, but mentioned her in his writings and Broude reflected on her influence on her grandson’s life in her book.

This picture seemed to frame perfectly all my worries of being a white feminist – a white blonde woman in a white dress with golden belt in front of the invisible generic woman of colour, bare-chested and nameless. The white woman, dressed to please the male gaze, impeccable in terms of society’s demands, actually more than that, because she was a superstar. I took a deep breath and thought about how this white woman was defying stereotypes with her clothes and sexuality, and her stance against the Nazis, but kept on wishing I could add an extra layer of intersectionality to her, like I was trying to do myself. But that was not the time. That was 1946, the Second World War had just ended. But today, at present, what do you see white woman? Take yourself back and dismantle settled notions. Is everything all right around you? Question your behaviour. Question what you are not considering. Turn yourself around and face the painting and not the photographer taking your picture. Ask her for her name.

The image of women of colour perpetuated throughout my youth defined the attention I gave them, they were barely around me, they seemed far away, hidden. I mistreated none but was ignorant about how they were mistreated, their invisibility and suffering. Left at the margins they rarely would reach higher education, and faced racism accessing proper health treatment. Still today, in Portugal children of colour are put in the back of the class, and mostly dismissed, their expectations of further education erased. In my early teens, I would sing, “My baby don’t care for shows,” but I was only familiar with its cute stop motion video and knew nothing of the civil rights warrior woman who wrote it and sang it. I didn’t know the lyrics for Work Song.

In the 1980s, in Lisbon as a child, I was frequently sent to the supermarket by my parents. On our street there was a corner building, seemingly uninhabited and in bad shape that I had to pass by. One day there was a lady sitting outside in the front of the building, on a small bench, in what seemed to be a moment out of necessity and not leisure. My heart raced as I passed her because she was shaking, holding on to her purse. Moreover, she had covered herself completely with some sort of shawl or blanket. I couldn’t see her face, as her upper body was fully covered. She was sobbing under the blanket. Her hands I could see, holding on to her purse. She seemed to be at that moment taking herself out of this vicious world, she was seen and not seen, hidden. I had no idea what to do and was too young to ask if she needed help. If you get reduced to less of a human being and people treat you horribly and violently, how do you rise? I have now learned that historically black women have always risen, grouped and organised by themselves, for their children, for their human rights. They have earned with every drop of blood, all that they are. Writing this doesn’t imply or diminish any other person’s suffering. But it does put things in perspective. Rather, if we concentrate our attention on society’s oppressed groups, we will all rise together. I have learned this by reading black women. One will take you to another. “What black feminists promised all along was true: to know the most present marginalized oppressions is to know the future.” Tressie McMillan Cottom said.

When writing about her connection to art at an early age within her family and being confronted with images of black women’s bodies, bell hooks told us that “Long before Paul Gauguin’s images of big-boned naked brown women found a place in my visual universe, I had been taught to hold such images close, to look at art and think about it, to keep art on my mind.”

Nickolas Muray portrait of Marlene Dietrich. Image altered by the author.

[Union Station is the frontier between NE and NW. H street is at the back of the station, elevated, in a sort of viaduct over the train tracks and surrounded by TV networks, some federal buildings, and a healthcare company, Kaiser Permanente, that always made me grin. “Permanente” is the Portuguese word for permanent. The health company was named after Permanente Creek, a word with Spanish origins, hence the proximity with the Portuguese language. But before 1907, the date the station was erected, around this area there was Swampoodle, a working class neighbourhood, first populated by Irish immigrants and African Americans who built the city, more precisely, their hands made the White House, the Capitol and other surrounding buildings all completed in the 1800s. Swampoodle was a name allegedly given by a reporter because of its puddles and numerous swamps, created by the overflowing of Tiber Creek (a tributary of the Potomac River).]

≊

PART III

Public Journal Entry [A Possible Bond]

“What did it mean for a black woman to be an artist in our grandmothers’ time? In our great-grandmothers’ day? It is a question with an answer cruel enough to stop the blood. (…) The agony of the lives of women who might have been Poets, Novelists, Essayists, and Short-Story Writers (over a period of centuries), who died with their real gifts stifled within them.”

— “In Search of Our Mothers’ Gardens”, Alice Walker (1983)

“We welcome all women who can meet us, face to face, beyond objectification and beyond guilt”

— “The Uses of Anger”, Audre Lorde (1981)

All this walking around in DC had some physical consequences. Like a blister the size of a pocket round mirror on the sole of my right foot. The sole, not the ankle, not the side, the sole, did you hear me, the soul. I still have a picture of it on my phone, before bursting it and removing the skin. I sent the picture to my niece, who was in medical school at the time. She told me to get a needle and some thread and place the thread across the blister. The thread would suck up the liquid and would help it dry. By the time her advice reached me I had already thrown my own skin in the trash and disinfected the whole thing in the hope I could still walk the next day. Her advice came not from medical school but from real experience – in her early twenties she already had under her belt not one but two prolonged journeys on foot from Lisbon to the Catholic Sanctuary of Fátima (127 Kms/79 miles), an actual pilgrimage site in Portugal. I was able to walk the next day. I carried on.

It will be upsetting sometimes, you will feel discomfort. A small pebble might find a home in your boot. You will make mistakes. There will be a lot of negative replies. A lot of silence. I don’t believe that in practical terms you can have “no expectations” about your endeavours and wishes, because our capacity to dream should not be diminished. But we should add a realistic view of what can happen or what small things can be accomplished. Just consider the path, you will stumble but you will also trot with confidence. When that happens, trot with joy. “Joy is made to be a crumb” (Mary Oliver).

This can take years. This walk towards a greater knowledge of history, of social injustice, of gathering solutions within what you do, your profession, in a way that you can be closer to being an ally. You cannot be an ally without being highly informed. You cannot be an ally until someone with authority to do so nominates you as such. You might think this is all a big exaggeration of mine, but fellow white women in the arts, those opinions and set beliefs you have had for years, where do they come from? Go to the root of it and dismantle it. Are they based in real study or on your surroundings and their limitations?

I should clear something up, I am not an activist. I will not abdicate working in the arts for true selfless work, driving non-profit organisations to fight real blood and sweat fights. An activist is someone who devotes the majority of their lives to causes. I don’t. I am only trying to apply change and justice to the path I have chosen. To my gender, to people of colour, to oppressed minorities. Considering a lot at the same time with some priorities, but checking myself and my actions and their consequences along the way. In order to perfect and inform what will end up being taken as my instinct and my capacities as a curator, an arts worker, but more importantly as a human.

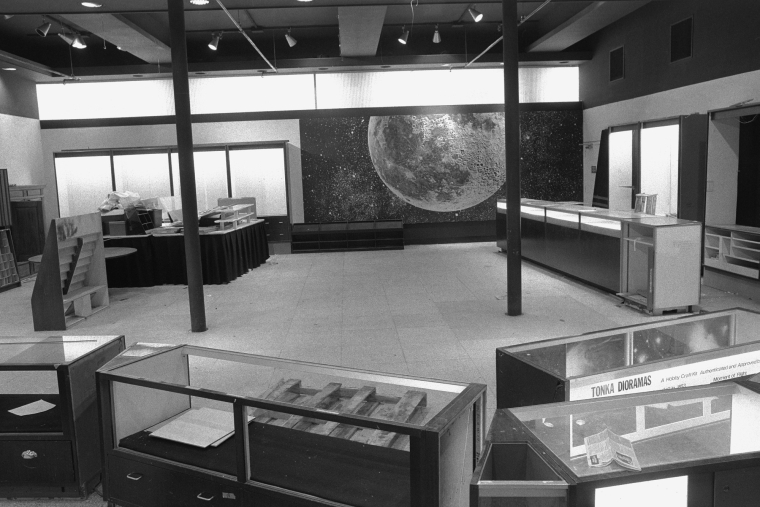

British Museum at Yale, May 1978. 1 photograph: colour transparency; 35mm (slide format). Call Number: LC-GB05- 7056 [P&P]. Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division, photograph by Bernard Gotfryd, [Reproduction number e.g., LC-USZ62-123456].

|

British Museum at Yale, photograph by Bernard Gotfryd. |

|

This photograph titled British Museum at Yale (now the Yale Center for British Art) is by Bernard Gotfryd, a photographer that survived six different concentration camps, immigrated to the US, worked as a combat photographer and later worked for over thirty years at Newsweek. In 1990, he released the book, Anton the Dove Fancier and Other Tales of the Holocaust, a project that was born after photographing fellow Holocaust survivors at the White House, followed by a trip back to Poland for the first time after the Second World War.

Gotfryd must have been sent by Newsweek to cover the museum in New Haven, Connecticut, founded by Paul Mellon, an art collector and philanthropist passionate about British art. The modernist building designed by architect Louis I. Kahn (his last building) had opened some months earlier in April 1977. The set of several photographs taken as indicated in May 1978, inside the museum, of which I have chosen one, seem to be of those couple of days just before the opening of a major exhibition perhaps. One shows a work table in the exhibition room, something temporary it seems, with some registers, others when seen together show what clearly seems like museum staff serving as human scale for the photograph. The same people placed in different positions around the exhibition rooms either observing paintings or engaging with each other on a sofa. No one has a handbag, or any kind of bag or coat. It seems the show was not opened to the public yet, so they were there simulating being viewers of the art works for the purpose of the picture.

In four different photographs, I recognised what seems to be the same black woman dressed in a white shirt, burgundy vest and green skirt. In the picture I chose, she is engaging with a white woman who is holding some folders with her left arm. The black woman also holds a small card. By what they are wearing, their interaction and my own visual dictionary, informed by good and bad social judgements and prejudice, they seem to work together and I would be inclined to say the white woman is probably a curator, and the black woman seems to be a gallery assistant. In the other pictures she is on her own, active, present and engaged through the exhibition rooms.

Playwright Lorraine Hansberry was a radical writer and activist, the first black woman to ever have a play produced on Broadway: Raisin in the Sun. I particularly love this ending to a letter she wrote to her boyfriend, showing her determination in the form of a manifesto:

“1. I am a writer. I am going to write.

2. I am going to become a writer.

3. Any real contribution I can make to the movement can only be the result of a disciplined life. I am going to institute discipline in my life.

4. I can paint. I am going to paint.

The END"

She spoke with the same determination when referring to teenage winners of a writing contest: “To be Young, Gifted and Black”. This sentence inspired Nina Simone, who knew the author but even so when she saw her picture in the New York Times was struck by Hansberry’s eyes, they were trying to tell her something. You can find this online, Simone explaining that photography has its own way of communicating and that it got hold of her, so much so that she wrote a song in her memory. The lyrics go, “to be young, gifted and black / is where it's at” (lyrics by Weldon Irvine).

Black female artists and essayists have been reclaiming their creativity and the imagery connected to their bodies. bell hooks writes about Lorna Simpsons’ Waterbearer, a photograph showing a black woman with a jar of water in each hand as reminiscent of Vermeer’s paintings of working women, but highlights the woman’s “defiant stance” – “by turning her back on those who cannot hear her subjugated knowledge speak, she creates by her own gaze an alternative space where she is both self-defining and self-determining.” hooks points out that Simpson demands that we take a deeper dive and that she aims to “rescue and recover” black female bodies, because the mainstream doesn’t depict the real depth of black women. That a black woman “is not herself but always what someone else wants her to be”. The naked woman in the sea of fully dressed people, the women in Gaugin’s paintings, the woman that hid herself underneath a blanket, the woman inside the museum.

This reclaiming by black woman artists is important to be witnessed, as spectators, as thinkers, as white women. Only then do we white women curators have the chance to understand/connect with work made by black artists. Do you know enough of other cultures to exercise the right to criticise or review their artwork? Which parameters are you using? Aren’t your western contemporary art parameters too white and inadequate? Have you considered that you have to stretch what you think is your taste in order to engage with art works from people of colour? Do you know enough about your own white race? It established oppression with other races, and devised the concept of race itself, so does that give you a hint not to turn defensive the minute something happens? Do you really think the white race needs “defending”? It is important for white women curators and researchers, that have difficulty even for a second in giving up their skin privilege in order to become allies, to read and understand the black female experience, and its clear differences. That will put things in perspective.

At the Library of Congress. Photograph by the author.

So, what does a white woman curator need to know? There is work to be done. Because art is also about justice, as Paley argues, it’s “the illumination of what isn’t known, the lighting up of what is under a rock, of what has been hidden”. But making minorities visible, dear Portuguese white woman curator, is not just “selecting” that one black woman artist, it is not just making that list of artists a little more equal in terms of gender, it is not just acting as a token woman, remaining exactly in the same position and going about as usual, specially if you are in a position of power. It is not just artists, but art writers, producers and curators of colour, a whole community that has to grow and rise to visibility. From margin to centre – I learned this from Grada Kilomba who learned it from bell hooks. This artistic production has to be reflected by specialists of the same culture. Also, there are archives to be made. There are young girls of colour who need to have every option available. They have to know, they can be an artist. There is justice to be applied. There is restructuring to be made. When you open the door to one black woman, do not think you are doing “good,” do not highlight the opening of the door, it is not enough. Do not gloat over your small action. A white woman curator needs to know that in this process her own notion of “taste” should be reassessed. She should realise that probably her parameters are limited by Western culture, and therefore are insufficient to critique other cultures. In the process of learning, an expansion of taste is bound to happen. But give it time. There is a whole world to consider, a whole Global South to open our eyes to. Whole relationships to be built and trust to be earned by both parties.

Museums in Washington DC were my place of rest from walking. There were so many of them. I joke, I love museums and what they do to my spirit, of course, in many fulfilling ways. In practical terms, they were always the final objective of my walk. The end game. The visual learning or unlearning, the worlds that opened up, the knowledge I instinctively held within me. Those Kara Walker drawings, the Alma Thomas paintings, that Kerry James Marshall painting of a girl sobbing in her library, that Kennedy portrait by Elaine de Kooning, that audience member looking at that person in Amy Sherald’s painting, that portrait of Diane Arbus holding one of her own photographs, that daguerreotype of a man c.1855 behind a newspaper covering his face, that Yoko Ono sentence written on a wall: “Relax. Your Heart is Stronger Than You Think!”. I kept on walking inside their walls, reaching every floor, every corner, every majestic room. I cherished those buildings but nevertheless questioned the reasons, their origins, their very existence. For certain, there were empty exhibit cases inside rooms I was not allowed to go into. Those can, and should, symbolise restructuring. Their glass might be dirty or clean, dust might be stuck in those wooden joints. Should new ones be built, should these cases be kept? All is still open while our lives run, while you slide the glass, or let it drop gently, to close it. You might be wearing white gloves. These exhibit cases will carry a myriad of different objects in different configurations, but all content will leave a mark.

I am no longer walking in DC, I have crossed the ocean back, but still feel suspended in desire, belief and future. This constant search, curiosity and thirst to learn sets what seems to be an unstable life. This instability should mostly be read as excitement. Would I be able to feel alive any other way? As long as we’re living there is no clear finish line, so I just want to keep walking beside you. One minute I might stop, another I might walk faster, you might do any of these variations. We might look each other in the eye, we might turn our backs for a while, but here we are, close, able to help each other out, at arm’s length. One day soon, I hope, profiting mostly from the same benefits and battling the same injustices. One day soon, I hope.

Gwendolyn Brooks, poet extraordinaire, has her name on several plaques I suspect, rightly so. Later in life, she wrote a poem for the unveiling of a sculpture of her own face, a homage, both sculpture and poem. She read it at a public event. Here are the last lines: “no longer walking through rooms, I shall be gone and not gone”.

LIST OF ONLINE RESOURCES

So, what does a white woman curator need to know? There is work to be done. Because art is also about justice...

Susana Pomba is an independent contemporary art curator and writer, who has been working in Lisbon for more than 20 years. One of her long-lasting projects was Old School, a series of fifty one-night events (2011-2018) that were housed in the space of Teatro Praga. She has collaborated with many art spaces, institutions and publications, either as a curator, writer, editor, translator, photographer or communication professional.

Empty Exhibit Cases gathers three cisgender white women working in the arts, Susana Pomba, Susana Gaudêncio and Maribel Mendes Sobreira, on their way to become life-long anti-racist and effective allies, as artists, teachers, researchers, curators, historians, writers, or authors. The project delivers a group of essays (in diary mode), that might be hybrid in form, and attempt to dissect various questions and struggles, all in the context of the daily personal and professional lives of the three participants. They will also engage in conversation with activist groups, scholars, or cultural agents.

Based on diary-keeping as a form of writing, the Mode Diaries initiative creates a field of interpretative potentialities within the context of maat Mode 2020, a public, experimental and participatory exhibition and activity programme under the motto “Prototyping the museum”. This is the scope that justifies and enables the twisting of the meaning commonly attributed to the term “diary” by transforming what’s individualised into collective, private into public, singular into plural, etc.