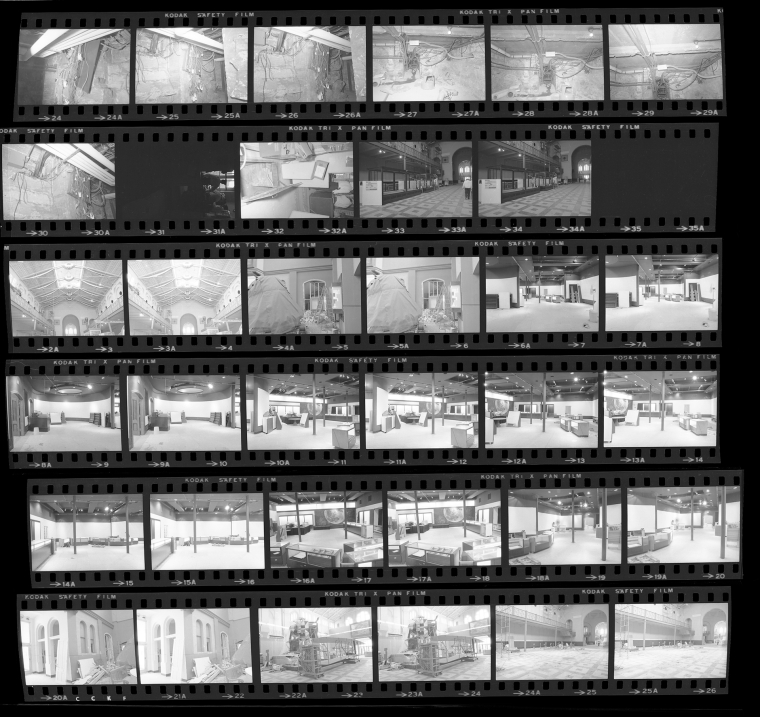

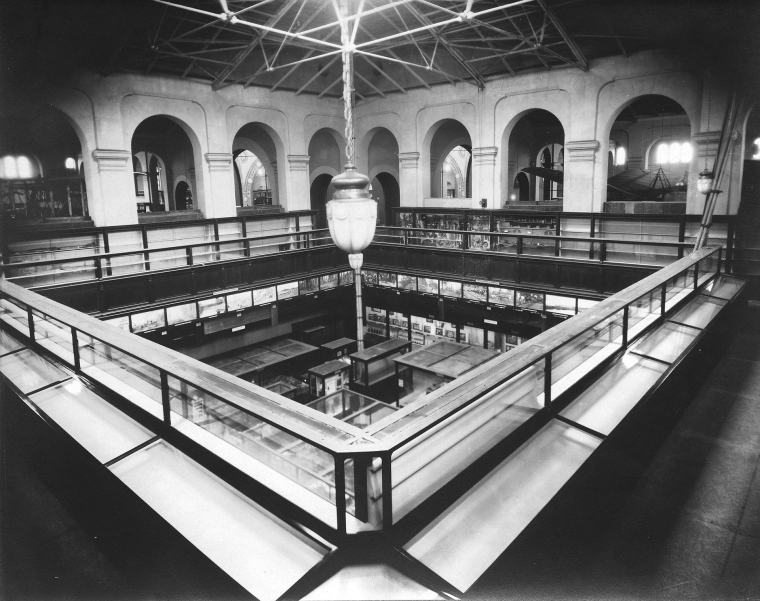

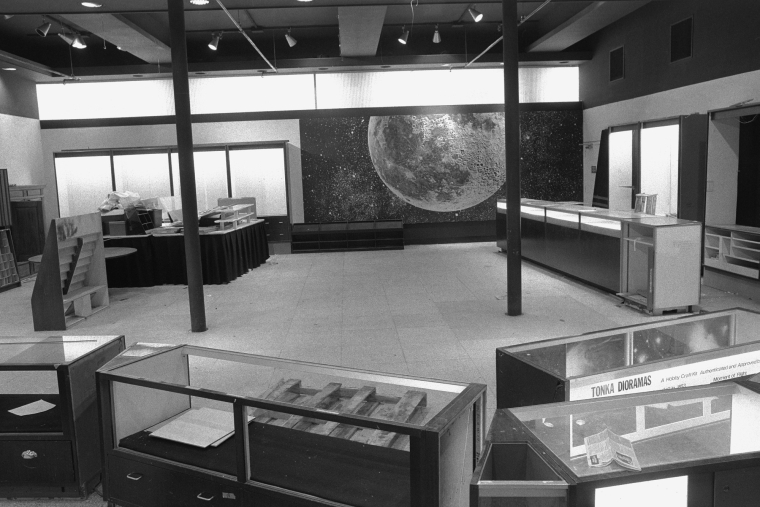

Empty exhibit case at the United States National Museum, now known as the Arts and Industries Building, 1880s, USA. © Smithsonian Institution Archives. Image #MAH-24053.

On 24 February 2021, we had a Zoom (private) conversation with Greek-born Lisbon-based Maria Vlachou, executive director of Acesso Cultura, moderated by Maribel Mendes Sobreira, with the participation of Susana Pomba and Susana Gaudêncio. This is the first of a group of three conversations included in Empty Exhibit Cases, an essay writing project that gathers three cisgender white women working in the arts, on their way to become life-long anti-racist and effective allies, as artists, teachers, researchers, curators, historians, writers, and authors.

Maribel Mendes Sobreira

Tell us about your professional background and when your interest in issues concerning accessibility first started.

Maria Vlachou

The first job I had in Portugal was as an English teacher at the professional music school in Almada, a very special school. It was there that I first had the opportunity to meet people that were part of the Portuguese cultural milieu, most of them musicians. Later, I was responsible for the press office at the Pavilhão do Conhecimento [Pavilion of Knowledge], where I had a colleague that was especially interested in issues of accessibility, specifically disabilities. We started working together. In 2003, at the pavilion, we organized a conference for the European Year of People with Disabilities, and we met other colleagues with similar concerns. At the time, we created an informal group called GAM, which preceded Acesso Cultura [Access Culture], to promote accessibility in museums. We looked at the problems of physical access for people with disabilities and also other types of barriers. During the ten years it existed, we resisted the idea of formalizing the group until we understood that in some ways it limited us. There were things that we wanted to do but couldn’t because we didn’t exist legally. Also, we realized that these issues didn’t just relate to museums. In 2013, we created Acesso Cultura. Initially, its aim was to improve physical, social and intellectual access to cultural spaces and events, but then its scope was broadened to include not only what people came to see but also what was going on among the staff and people who liked to think about culture as a possible career, in the many areas that comprise this sector. So, in 2019, we adapted our mission to reflect this widening of scope more clearly. It became “to promote physical, social and intellectual access to cultural participation”, with all that that implies.

Maribel Mendes Sobreira

Were you paying attention to what was happening abroad and how these issues were developing?

Maria Vlachou

Always. Because most of our inspiration came from other countries, where things were a little bit more advanced. We didn’t want to start from scratch when some of the work had already been done; it doesn’t make any sense to be constantly reinventing the wheel. We have to learn from people that have tried, that have made mistakes, and we adapt it to our reality. We have always looked outside Portugal to see what is going on and to think about our context. Later, I was very lucky to be accepted for an Arts Management Fellowship at the Kennedy Center in Washington D.C. It was there that Accesso Cultura was created, as my project in the course. I learned a lot with the team at the Kennedy Center, and with the great diversity of fellows, that came from all over the world. Some people worked in big formal institutions, others had their own projects and it was really a great opportunity for learning, tremendous.

Maribel Mendes Sobreira

How do you work with the concept of inclusion? It can be seen in different ways, and there are many misunderstandings.

Maria Vlachou

Until quite recently, we had a very paternalistic idea concerning inclusion. I don’t know if you have read John Holden’s “Culture and Class”, where he talks about the “guardians of culture”. There are three categories, the middle one being the “neo-mandarin” [the other two are the “cultural snob” and the “neo-cosmopolitan”], who really wants to create access but is the one who decides what is worth having access to: “I decide, I am a good person and I am sharing this with you.” For a long time, this was our attitude and understanding, that is to say, we had very good intentions about creating access, but it was up to us to define what that access was to. We grew, we saw and listened more, and we launched a course in exactly these areas that allowed us to read and learn more about certain issues and to share them with colleagues. Because it’s not about generosity, it’s not about being good people or not, it’s really about being aware of what our role is in society, as citizens and individuals but also through our work in the area of culture. And culture is not only art; it’s related to several aspects of our lives and the way we organize ourselves in society. What we talk about in the course is that diversity is a fact of life, it’s not something that depends on us, we’re not going to “promote” diversity, diversity exists. When we recognize that, thinking about inclusive spaces, or about politics of inclusion, becomes about creating welcoming spaces that recognize people as a whole. A person doesn’t have to leave part of themselves outside the door, to erase part of themselves, so that they can come inside and be with others, work, give their opinion and have that opinion respected, and not considered only a suggestion. Once again, we are good people, we accept suggestions, but then we don’t really pay attention to them. Maybe over the last two years this has been more of our focus and learning.

Maribel Mendes Sobreira

How do you see participation within inclusion, from an intellectual and financial point of view, but also in terms of race and gender? How can we really create something truly participatory from all sides?

Maria Vlachou

I think I would approach this in two ways. First, when it comes to participation in a professional context, we have to ask ourselves how we can create spaces, organizations, and projects where people who are not part of our usual bubble (the group of people with which we normally collaborate) can feel welcomed, taken care of and respected. That requires being humble. Till now we have been too confident in our accomplishments, and maybe the first step is to recognize that there are many things we are ignorant about, things that are happening right now just around the corner but which we have never paid attention to. We need some humility and courage to do things differently. These two qualities in people are essential for change — humility and courage to take a chance, to do things differently and to question ourselves, our practice and our way of thinking. Some years ago, the theme of our annual conference was “participation” and Marta Silva, from Largo Residências, was very critical of several of the projects we call “participative” but which in reality are not. Because we are the ones who define the whole project and then we invite several people who normally don’t work with us and are not in our circle, who we sometimes call “community”, to come and do what we have already envisioned. We need to be very respectful of the people we are inviting. We have to change our attitude and the way we talk. We need to think carefully about why we do what we do.

Until quite recently, we had a very paternalistic idea concerning inclusion. (...) we had very good intentions about creating access, but it was up to us to define what that access was to.

Maria Vlachou

Susana Pomba

We all work in culture and we are privileged white women working within pre-established patriarchal structures. With the “best intentions”, how and where can we position ourselves?

Maria Vlachou

I’ve thought about that a lot, for several reasons. We recently ran the second part of the course Diversidade e Inclusão [Diversity and Inclusion]. Accesso Cultura is an association of white arts professionals – we don’t have people from other origins. In the last two or three years, our first colleagues with disabilities became associates. The first ones. We now have three. Things take time, even just for people to trust us. And I feel that along the way, while building a relationship from scratch, and in order to take some steps forward, there are going to be situations in which some people will be put in a position of being affected by tokenism. Is it inevitable? I was unable to avoid it. We are an association of white people and in the events we organize the vast majority of people are white. We need that other voice. But when I invite them, considering our context, I put them in a fragile position. The moment that person shares an opinion, a vision of the world that is not the one we are used to, that might be shocking to some people, which is normal, that person is left all alone. I remember inviting Wayne Modest from the Tropenmuseum two years ago for the seminar about the decolonization of museums. There was a moment, while we were still preparing the session at a distance, in which he asked “And are you going to protect me?”. And I didn’t understand what he meant. Later, after a few more conversations, when he was invited back by the Gulbenkian Foundation, I understood what he meant. I would have done it anyway, not in the way he meant (as the only black person on a panel) but because it would have been rude to allow a guest to be mistreated and left in a vulnerable position. Understanding what he was referring to was a learning experience. He could have been subject to micro-aggressions that I wouldn’t have been able to identify, but he would. And, in that case, I wouldn’t have been able to protect him. Recently, we organized a seminar where ideas were discussed concerning the appropriation of Black Lives Matter. I felt that my guest was completely alone defending her point of view. Could I have avoided that? I don’t know how. Maybe, if I had invited other people, maybe if I had told her to “invite whomever you want”? I don’t know. Not too long ago, I intentionally invited someone to attend our course in order to give me feedback. She listened and also intervened in the conversation. After seeing the way we approached issues, she said: “I belong to an association, we should think about collaborating.” Things opened up a bit more in this case, which is to say that each of us is dedicated to a different group of people and we will be able to collaborate and join forces. In this way, we can avoid that situation where someone is all alone on a panel full of white people who have never thought about things from other points of view. But to get to this point, it means I have put three, four or five people in that fragile place. I don’t know if I could have avoided that. I have to discuss it more with other people.

We are talking about how to deal with micro-aggressions, and it seems to me it’s connected with the mother of all subjects: language. The way we use words and which words we use.

Maribel Sobreira

Maribel Mendes Sobreira

We are talking about how to deal with micro-aggressions, and it seems to me it’s connected with the mother of all subjects: language. The way we use words and which words we use. For this project [Empty Exhibit Cases], we have thought a lot about it. That we may need to create a guide. The journalist Teresa Vieira, because of the assassination of Gisberta, the use of very violent and aggressive language and the overall treatment in the press of the LGBTQIA+ community, created a group to write a guide to good journalistic practices in order to help reporters address certain themes. Shouldn’t the Ministry of Culture have a manual for more inclusive language in professional settings?

Maria Vlachou

Yes, yes. I don’t know if you saw the story about an American museum [The Indianapolis Museum of Art] that because of the so-called “diversity” stated on a job posting they were looking for a director who could attract a “broader and more diverse audience” while maintaining its “traditional, core, white art audience.” Very quickly, the job posting was rewritten and the head of the museum resigned. The issue of language is fundamental for us and for me personally words carry weight and power. We have to be aware of what we say at every moment. For me, being politically correct means being polite and respectful to other people, just that. It’s not strange to me to make an effort to treat the other as they wish to be treated. I think language evolves together with our understanding and our practices, and we have to keep up. We made a manual about issues to do with disability and incapacity, because we felt that people were very afraid of saying the wrong thing, of offending others. For instance, we call people with a visual disability, invisuais [in English “non-visual” or “unsighted”] and they hate it. We think it’s more polite, but to them it sounds like “invisible” and they really don’t like it. Because of that, we created a small chart but with a warning – that these things change constantly. In the English language, some people identify as “disabled people” and others as “people with disabilities”. What do you put first? The person or the disability? There’s no right answer, people identify as much with one thing as with the other. You have to be sensitive, to observe and to listen how the other identifies. In Portuguese, this nuance doesn’t really exist. In Portugal, journalist Dora Alexandre, who hosted the RTP2 show Consigo [By Your Side], created a manual for the press about disabilities. It is very useful but may already be outdated in some ways. The European Union has policies concerning more inclusive language. The manuals exist, but we have to be aware that, more than any manual, we have to be sensitive, pay attention and see how the other person wants to be treated.

Maribel Mendes Sobreira

And how do you see Portugal within the international scene with regard to the implementation of these policies, the use of inclusive language, the issues of intellectual and physical inclusivity, and race and gender. Is Portugal going in the right direction or is it still far behind?

Maria Vlachou

We are behind. I would say that we are not actually moving forward, because we are still living the first moments of the clash. We are still at a very initial phase. Some people and organizations are trying to adapt, trying to walk at the same pace as society, but I would say that we are still in the beginning, and that these ideas are still seen as foreign. Any country of white people finds it immensely difficult, and there is a lot of resistance when these matters are raised. Independently from their past, and even countries with no colonial history. Formal entities and cultural organizations don’t reach out to us concerning these issues. We mostly have a lot of contact with technical staff who enrol on our courses individually and come to our debates. Directors rarely show up. Where are the directors? What the technical staff tell us is that the first barrier is internal.

Susana Gaudêncio

I am a teacher at ESAD – IPL [School of Arts and Design] and during my eleven years there, I’ve only taught six or seven students of colour. I am interested in understanding why this happens and what I can do about it. Maybe by highlighting antiracist and inclusive learning strategies.

Maria Vlachou

I can share with you that that will be one of our priorities for 2020–2021 – bringing awareness among art teachers and others. Someone we know, with restricted mobility, wants to be an actor and wrote to a school. They received a brutal and ignorant reply that totally disregarded the work of artists with disabilities in Portugal and around the world. So we thought it was better to start with the teachers themselves. But also taking into account, since you were talking about students of colour, that many people are left behind. Paula Cardoso from Afrolink said in an interview that as she progressed in her studies, her peers gradually disappeared. In high school, she was the only black person in her class.

Susana Gaudêncio

I think it was Cristina Roldão who researched exactly that for her PhD – the type of choices that afro-descendants make in Portugal. Why they choose professional studies rather than the humanities or the arts. And we can see why.

Maria Vlachou

Something that was even more shocking to me was the case of Piménio Ferreira, a Roma scientist that in an interview said that in primary school the teacher looked at him and the girl beside him and told them, “I don’t know what you are doing here. You are going to clean houses and you are going to work at fairs.” A teacher in primary school – this limits everything right then and there. One’s imagination is restricted, stuck, “That’s all I can be and I can’t dream of being anything else.” There’s a great deal that the arts can do in this situation. Concerning this issue of imagination, we have to see other people on stage, other people in the staff. Who is the floor manager? Who is the lighting technician? Who is the person that leads the guided tour in the museum?

Maribel Mendes Sobreira

You wrote an article for the newspaper Público about “curating the discomfort”.

Maria Vlachou

Yes, curating the discomfort. I wish I had come up with that. I only borrowed the expression, it’s lovely. In the article, I talked about a wider network of education and culture. It’s not only in education or the theatre or a museum. We all have to think about our role, each one of us in our own fields. The judges in the courts, the security forces, the way the police treat citizens, the way we are treated in government offices – all of this is culture and what we are as a society. When a judge makes a decision concerning a woman that has been assaulted, this concerns everyone. It has to be discussed in school, it has to be approached in cultural spaces.

Susana Pomba

What you are saying really is that we all have to be a little bit of an activist at all levels – in our profession, in our home, and in the situations of injustice that we witness.

Maria Vlachou

People feel powerless because they think these issues are very big and that they can’t make a difference. The first difference that I am trying to make is in how I raise my son. It’s right here, close, next to me. And my son now discusses a series of things in his philosophy class with his colleagues and his teacher. There you have it, a little bit wider. Tomorrow, he will go to university and then he’ll start a career. That is my first contribution and then, yes, by making a change at work. This is change that each one of us can do, on our own scale. The issue of scale is very important, so that we don’t undervalue the small amount we can do. Angela Davis says that we have a tendency to talk about the great heroes, like Mandela, but Mandela himself insisted a great deal that we talk about the people that accompanied him in his struggles. If we only talk about heroes, this makes a lot of people think, “I am not that”. We take away the potential that each one of us has to make a change, even if just within our families. There is a very beautiful video in which Nobel Peace Prize winner, Kenyan Wangari Maathai, tells the story of a great fire in a forest and how all the animals, including a lion, were very scared. Then we see a hummingbird getting a little bit of water to try to put out the fire. The other animals ask: “What are you doing?” And he answers: “I am doing the best I can.” Sometimes that’s what I feel, I am doing the best I can.

... we all have to be a little bit of an activist at all levels – in our profession, in our home, and in the situations of injustice that we witness.

Susana Pomba

A cultural manager and communications consultant, Maria Vlachou is a founding member and executive director of Acesso Cultura [Access Culture], which promotes physical, social and intellectual access to cultural participation. She is author of the bilingual (Portuguese and English) blog Musing on Culture in which she writes about culture, the arts, museums, cultural management and access to communications. She manages the Facebook group Museum texts and co-manages the blog Museums and Migration. She participated in the European project RESHAPE – Reflect, Share, Practice, Experiment, having joined the trajectory “Arts and Citizenship”. She was previously communications director at the São Luiz Municipal Theatre and head of communications at the Pavilhão do Conhecimento – Ciência Viva (Lisbon). She was a board member for ICOM Portugal (2005–2014) and was editor of its bulletin. She has collaborated with different programmes organised by the Gulbenkian Foundation. She is a Fellow of ISPA – International Society for the Performing Arts (2018, 2020) and an alumna of the DeVos Institute of Arts Management at the Kennedy Center in Washington (2011–2013). She has an MA in Museum Studies (University College London, 1994) and a BA in History and Archaeology (University of Ioannina, Greece, 1992).

“Empty Exhibit Cases” gathers three cisgender white women working in the arts, Susana Pomba, Susana Gaudêncio and Maribel Mendes Sobreira, on their way to become life-long anti-racist and effective allies, as artists, teachers, researchers, curators, historians, writers, or authors. The project delivers a group of essays (in diary mode), that might be hybrid in form, and attempt to dissect various questions and struggles, all in the context of the daily personal and professional lives of the three participants. They will also engage in conversation with activist groups, scholars, or cultural agents.

Based on diary-keeping as a form of writing, the Mode Diaries initiative creates a field of interpretative potentialities within the context of maat Mode 2020, a public, experimental and participatory exhibition and activity programme under the motto “Prototyping the museum”. This is the scope that justifies and enables the twisting of the meaning commonly attributed to the term “diary” by transforming what’s individualised into collective, private into public, singular into plural, etc.