Notes on privilege, bodies, statues and the public sphere

Essay and drawings by Susana Gaudêncio for the Empty Exhibit Cases project

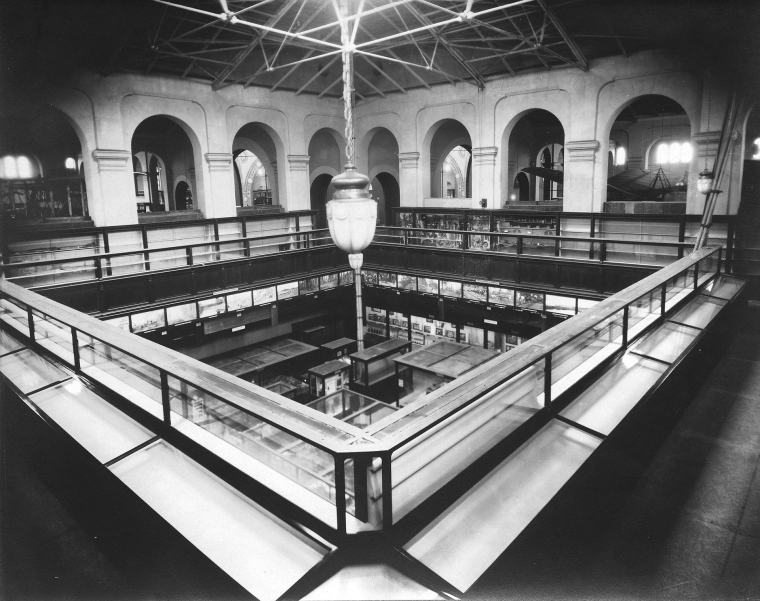

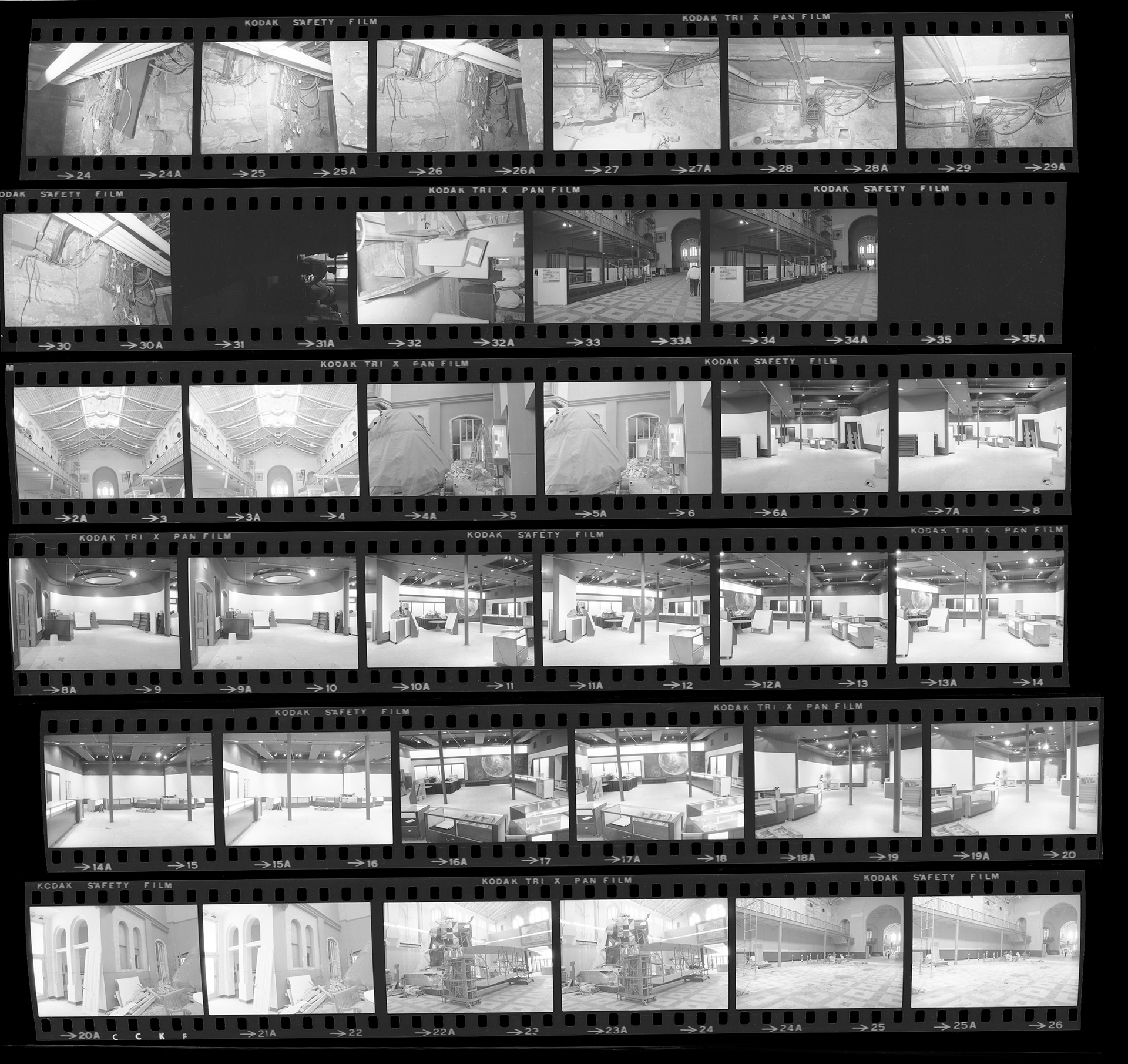

Contact sheet of empty exhibit cases at the United States National Museum, now known as the Arts and Industries Building, 1880s, USA. © Smithsonian Institution Archives. Image # SIA75-11093.

1. Note on Privilege I

Verbs of the day: to be born, to grant privilege to, to glorify, educate, erase, silence, explore, contest.

Location: My name is Susana, I am a Portuguese woman, artist, university teacher, born white and into privilege, in a lower-middle class family from Alentejo (Portugal), with little formal education until my generation. I was born in Lisbon, in full democracy, after the Portuguese April revolution. My learning experience concerning Portuguese history, particularly the one that refers to the great sea journeys was, initially, rooted in narratives of glory, nostalgia and white superiority. This version of history disseminated through school textbooks was also accompanied by school trips to monuments, architectural landmarks and several museums. Many of these places still perpetuate this version of history today. I only later became aware that these narratives silence stories of oppression, criminal slave trade ideologies and ways of exploiting human life that still have repercussions today in the life of other Portuguese people.

Because of this historical scam, I only later encountered post-colonial and decolonial studies, which encompass protest actions against some monuments in public space and what they represent – an attitude that isn’t new but that now rises with new features.

2. Violence Went Out in the Streets

Verbs of the day: to assault, offend, normalise, suffer, oppress, regulate, control.

In many democratic countries legal and political power is exercised not only in the raising of a statue in public space but also through an immense universe of images, from art to advertising. Among other things, this power resides in the possibility of occupying the public sphere with some bodies excluding others.

Art that enters the public sphere can be received as a provocation, as an act of violence. The interpretation of these objects will always depend on the identity and the location of the observer (as defined by Adrienne Rich in “Notes Towards a Politics of Location”, 1984), it’s not a stable thing and can be fought against by distinct communities that share public space among themselves.

In the essay “The Violence of Public Art: Do the Right Thing” (1990), W.J.T. Mitchell mentions three types of violence that can be used in these objects:

“We may distinguish three basic forms of violence the images of public art, each of which may, in various ways, interact with the other: (1) the image is an act or object of violence, itself doing violence to beholders, or ‘suffering’ violence as the target of vandalism, disfigurement, or demolition; (2) the image as a weapon of violence, a device for attack, coercion, incitement, or more subtle ‘dislocations’ of public spaces; (3) the image as a representation of violence, whether a realistic imitation of violent act, or a monument, trophy, memorial, or other trace of past violence.”

As an example: while some white Portuguese accept the monument Padrão dos Descobrimentos (Lisbon) as a symbol of national glory and bravery, others, like Portuguese people who are descendants of enslaved people, can argue that such a symbol represents an unbearable act of violence, an attack on their own existence. That dispute of meaning is a central theme for post-colonial and decolonial discourse and especially in the context of institutional and public space exclusion policies.

Which strategies can we follow to re-signify public space? And reframe monuments, memorials, toponyms, urban design and other representations?

2.1 The Removal of the Statues

Verbs of the day: to remove, take down, destroy, demolish, dismantle, archive, store, reinstall, celebrate, parody, reintroduce, re-contextualise.

In the Soviet Union (1922-1991), thousands of monuments were built and disseminated with the intent of affirming the totalitarian power of successive leaderships, establishing them in history. With its dissolution in 1991, the Russian government made the preservation of the Red Army’s monuments one of the conditions for withdrawing their troops from newly independent countries.

However, the countries that emerged from soviet domain dealt with this legacy in very different ways. In the countries that opted to be closer allies with Western Europe, the majority of soviet statues and monuments were destroyed or taken down. The ones that were left were relocated and re-signified in theme parks, like Grutas Park (also known as Stalin World) in Lithuania or Memento Park, in Budapest, Hungary.

|

The statues of Lenin, Stalin and Trotsky at Grutas Park, Lithuania, 2000. Drawing by Susana Gaudêncio, courtesy of the artist. |

|

When they regained their independence in 1990, Lithuanian citizens took it upon themselves to remove soviet statues. After a parliamentary debate, the new government decided to store them, withdrawing them from public space. In a controversial decision that faced considerable opposition at the time, Lithuanian tycoon Viliumas Malinauskas asked the country’s officials to give him more than eighty sculptures so he could make an open-air museum with private funding. This soviet theme park – Grutas Park, was created in the National Park of Dzūkija, a dense forest area. Their new spatial and geographical context pulls them away from places of political power, symbolically circumscribing the extinct soviet system. The statues are not completely isolated from the history they were a part of the figures are grouped according to their role in the soviet narrative, as an example: the Totalitarian Sphere includes the most important leaders and ideologues; the Red Sphere presents the members of the resistance; the Death Spheres shows the bloody methods that kept the regimes alive. Besides the statues, the park includes reconstructed soviet prison camps or gulags: wooden paths, watchtowers and barbed wire fences. Despite an ambiguous and controversial stance when it comes to the soviet regime, the Grutas Park remains a relevant example of how statues can be re-contextualised. While countries deal with a difficult past and consider the legitimate place for their problematic monuments, the model of the park offers something other than a museum, or the destruction of the statues.

Muzeon Park is a part of Gorky Park, an urban oasis near the river in the city of Moscow, Russia, where abandoned soviet statues are kept company by hundreds of contemporary sculptures, including characters of traditional stories, literary figures and works that are more abstract. Sometimes this cohabitation brings subversive symbolic connections: a pink granite Stalin that lost its nose while being dismantled, with a half hidden hand in his coat, stands in front of a contemporary art installation with 282 stone heads piled up in what seems like a cage, symbolising the soviet dictator’s countless victims. Its creator, the sculptor Yevgeny Chubarov donated this work to Muzeon Park with the condition that it would be exhibited next to Stalin.

2.2 Revised Monuments

Verbs of the day: to review, re-signify, reread, relearn, reorganise, retell, include, restore, reformulate, destabilise...

|

Headless Women in Public Art, a walk by Mariana Morais, Porto, 2019. Drawing by Susana Gaudêncio, courtesy of the artist. |

Mariana Morais’ Headless Women in Public Art is a project that promotes a critical re-reading of the work of art in the public space in the city of Porto, Portugal, bringing to light an exclusion, the woman with agency. Mariana Morais gives us a map rooted in the principles of feminist cartography that actually references maps in order to lay bare fundamental issues about inhabiting a woman’s body, in opposition to a geography and cartography that traditionally ignores subaltern bodies, producing and reproducing oppressions and violence in public space and beyond.

Presented for the first time in Porto in 2019 as part of her artistic research project for her master’s in art and design of public space (Faculdade de Belas Artes da Universidade do Porto), Headless Women in Public Art examines public art through a woman’s perspective. Morais writes, the project aims to “identify, reorganize, reflect, give space and promote narratives related to women. It promotes more diverse histories about women in public art as a way to critically comprehend how common representations of the feminine are still affecting ‘real women and their social frame.’” (headlesswomeninpublic.art).

Traditionally, cartography interprets the human experience as masculine and denies or trivialises women’s experiences. Standing in opposition, Headless Women in Public Art is a tool that organises the representation of women in public space in four categories: Headless Women, Non-Women, Honoured Women, Women Artists; and creates specific routes in the city of Porto that include statues, monuments and sculptures. The project has different versions, online and print, and also offers something beyond digital media, for example tours that incorporate in-person storytelling by the artist, offering a re-reading and re-signification of gender in public space. Morais aims to highlight and establish the presence and fundamental force of women in the public sphere of a specific community.

|

“Blindly sailing for monney, humanity is drowning in a scarllet sea, L.I.A”, graffiti at Padrão dos Descobrimentos, 2021. Drawing by Susana Gaudêncio, courtesy of the artist. |

|

A monument made by architect Cottinelli Telmo and sculptor Leopoldo de Almeida, Padrão dos Descobrimentos in Lisbon is the focus of historical questioning made by artistic, critical and activist interventions. Built for the first time in its temporary version in 1940, on the occasion of the exhibition of Portuguese World, a final, permanent version was made in concrete and stonework in 1960 to commemorate the five hundred-year anniversary of the death of Infante D. Henrique [Prince Henry the Navigator]. In Descoberta [Discovery] (2007), a photograph by Angolan artist Kiluanji Kia Henda, presented inside the monument in the exhibition, Racismo e Cidadania [Racism and Citizenship] (2017), we see a group of young afrodescendants at the top of one of the ramps of the monument, overshadowed by its colossal scale, posing next to historical figures. The group is composed of eleven elements, including one woman, contrasting with the group of masculine historical figures represented in the monument. The title is an ironic allusion to the “discoveries” invoked by the monument but also to the “discovery” of the area of Belém, a place with an enormous symbolic colonial charge. The group came from Alta de Lisboa, a neighbourhood in Lisbon with an extensive African and afrodescendant community, and this was their first visit to Belém. The artist points out: “It’s necessary to re-think what is our objective when we glorify certain periods of history and to what extent it can be offensive for certain people that also inhabit the same city. History is made of different perspectives and there is an attempt to glorify the period of discoveries as something foundational in the Portuguese identity, which is perpetuated up to the present day, and which actually shows the existing reluctance in an African presence and its contribution to what the city is today.” (Translated from esquerda.net).

In this image, there are two opposite versions of history: the one that uncritically commemorates the “discoveries,” showing heroic figures on the bow of a ship; and then the version that was made invisible by the rhetoric of the New State [Estado Novo] (an invisibility that is largely still perpetuated today) – which is the version that tells us about, among other things, the slave trade associated with the “discoveries” and Portuguese colonisation. The highlighted presence of people of colour in the monument destabilises its glorious and optimistic symbolism, disassembling the hegemonic narratives associated with it.

Leila Lakel, a young French-Maghrebian activist, a student at L’Ecole d’Art in Paris, also confronted those same two narratives in a pressing way in August 2021, while on a brief visit to Lisbon. On the Padrão dos Descobrimentos, across twenty-metres, she graffitied the words, “Blindly sailing for monney, humanity is drowning in a scarllet sea, LIA”. At the time, there was an investigation by the police, which identified the author as “a foreign citizen, who has performed similar acts in other places, and who has since left Lisbon”. The Lisbon municipality erased the graffiti two days after the episode.

2.3 Performative and Nomadic Monuments

Verbs of the day: to inform, educate, subvert, participate, share, find, remember, communicate, emancipate, empower.

Monuments in public space are frequently made to convey historical, political, ideological information, this way perhaps developing an active socio-political power. They can be used to reinforce this power and its supremacy, like Stalin or Lenin’s omnipresent statues in the Soviet Union, or the equestrian statues of emperors and monarchs, all over Europe. These statues can be used as educational tools to teach the population about events or figures of the past that are considered important. To fulfil those informative and pedagogical functions, a monument needs to be in public space. In the context of contemporary art, there are monuments or memorials that adopt strategies close to artistic social practices, that are critical in their nature and deconstruct the idea that a monument should be fixed, or represent a monophonic voice of power.

|

ŠTO TE NEMA by Aida Šehović, (2006-2020). Drawing by Susana Gaudêncio, courtesy of the artist. |

Created by Bosnian artist Aida Šehović, ŠTO TE NEMA [Where have you been?] is a nomadic, temporary monument to the victims of the Srebrenica genocide in 1995. The project was shown in fifteen cities between 2006 and 2020. This participatory public monument, composed of more than 8,372 fildžani (small coffee porcelain cups), donated by Bosnian families from all over the world, addresses issues of trauma, cure and remembrance through a performative and collective ritual. The number of cups corresponds to the number of Muslims killed in the genocide. Unlike traditional monuments that are static and permanent, each ŠTO TE NEMA event happens annually on 11 July (the anniversary of the genocide), presented in a public space, each time in a different city, where passers-by are invited to fill their cups with coffee and participate in a ceremonial moment of great importance. In the artist’s words:

“Coffee drinking, or I would say, coffee sharing, is probably the most symbolic of Bosnian culture and tradition. The emphasis is on sharing, not on coffee. [...] When I was doing research about Srebrenica, what struck me the most was a story that I came across about a woman who said that she missed her husband the most when she didn’t have anybody to share coffee with. [...] a cup of coffee waiting for somebody became a clear, simple gesture that said so much.” (Interview to Art Margins).

Through art, the monument promotes, the practice of meeting people, and makes possible several different reflections: about the normalisation of violence and about what it means, in the daily life of the people who are left behind to cope with the loss of someone in such a violent way.

The Commons was made by Paul Ramirez Jonas, an American artist that grew up in Honduras. The sculpture is another curious example of a democratic and participatory monument – a glorious horse in cork rests on a base of layers of the same material, where the public can pin small written messages on pieces of paper or post-its. This horse is a replica of the one represented in the famous equestrian statue of the Roman emperor Marcus Aurelius (c. 175 BCE), which stands in the Capitol Square in Rome, Italy. While this equestrian statue of the emperor exists in public space in an enduring way, made out of bronze, symbolising power, the unique voice of the state, the singular identity of the hero and of something permanent, The Commons – a title that can be understood and translated as “Public Domain” – allows a plurality of voices because it invites people to participate. The public (a collective agent) is invited to write and share their thoughts, desires and aspirations pinning them on the statue, making a small gesture of democratic commitment possible in public space. “Cork is a material that can ‘publish’ an endless number of voices,” says Ramirez Jonas.

2.4 The Equestrian Project

Verbs of the day: to revise, desire, liberate, replace, reunite.

|

The Equestrian Project, by Susana Gaudêncio, 2008. Courtesy of the artist. |

|

In 2008, I made an artwork called The Equestrian Project, as a result of a reflection on public space, art and its monuments – more specifically equestrian statues, and the urban narratives that rise from that. As a woman artist, I was looking to create a subversive symbolic gesture amid Western history, usually dictated by the male soliloquy. The Equestrian Project (2008) is an audiovisual installation composed by three projections and a document (a letter). The exhibition space follows the format of a square, Terreiro do Paço in Lisbon, which is the initial setting of the narrative. Each one of the projections replicates one side of the square. On the fourth wall, there is a letter addressed and sent to António Costa, at the time the president of the municipality of Lisbon. The content of the piece (distributed across three video-animations) tells the story of the liberation and escape of the horse in the equestrian statue of D. José I, which occupies the centre of the Terreiro do Paço square. The escape of the horse is accompanied by a roaming camera that follows his journey to freedom, which includes an urban itinerary through the interior and suburbs of the city, and a sea crossing to reach his natural habitat, a hypothetical desert in North Africa, where he will join his herd.

As a rule, an equestrian statue commemorates the deeds of military and state leaders who seek to emphasise an active leadership role. The Equestrian Project was inspired by the Situationists and a desire to liberate all horses of equestrian statues, this way kidnapping or destroying the state figures represented in them, making them obsolete as symbols of power and oppression.

My intention was to create a poetic event that would give a passer-by a feeling of liberation towards perhaps, an authoritarian, normative or hegemonic context. At first, a letter was sent to the president of the municipality of Lisbon asking him to loan the equestrian statue of D. José I for one month so that the horse could be freed. This letter initiated a dialogue with the reality of the everyday, becoming also a conceptual argument to set in motion the imagined liberation plan. With no official answer, a fictional narrative was created in a video-animation format accompanying the story of this horse.

3. Dominated Bodies

Verbs of the day: to exclude, persecute, incarcerate, segregate, oppress.

In an article of the 1956 Internationale Situationniste #2 Abdelhafid Khattib, a situationist of the Algerian section of the movement, presents an in-depth psycho-geographic study of the area Les Halles in Paris – a territory of urban transition, where there is “social deterioration, acculturation and the intermixing of population”. However, his study was incomplete and it was interrupted many times due to the curfew imposed on Arabs in the streets of Paris – a segregation law that developed out of historical context of the Algerian War of Independence (1954-62). In a footnote to the article, the following note was added:

“This study is incomplete on several fundamental points, principally those concerning the ambient characteristics of certain barely defined zones. This is because our collaborator was subject to police harassment in light of the fact that since September, North Africans have been banned from the streets after half past nine in the evening. And of course, the bulk of Abdelhafid Khatib's work concerned Les Halles at night. After being arrested twice and spending two nights in a holding cell, he relinquished his efforts. Therefore the present – the political future, no less – may be abstracted due to considerations carried out on psychogeography itself.” (salvage.zone).

The public sphere is made of exclusions, segregation and omissions. For instance: many of the monuments, statues or public art in Portugal was partly financed by the slave trade. There is a collective amnesia that glorifies colonial remembrance at the expense of the memories of the subaltern. There is no space for a counter-narrative, we could say. After all what promotes these politics of memory and forgetting today? Is it possible for the municipality of Lisbon to accept a memorial to pay homage to enslaved people through Participatory Budgeting (2017/2018) and, simultaneously, as a result of official cultural policy, plan a Museum of the Discoveries? By analysing its monuments, we could conclude that Lisbon is a city that still glorifies the colonial and imperialism of the great navigations, a legacy imposed from other times, but that hasn’t been updated or re-contextualized, and on the whole exists with no visible or systematic critique.

4. The Statues That Fall

Verbs of the day: to revolt, protest, overthrow, undo.

"Liberatory work rooted in an understanding of different oppressive systems as entangled and dependent upon each other requires a shift of focus, away from innocence and towards complicity."

Sherene Razack

Some social movements of the last two decades, like Black Lives Matter (2013) or #Me Too (2006), publicly denounce differences and imbalances in opportunities between white and black people, women and men, and even though they have stirred the pot in the public sphere, they haven’t been able to make a profound change in the system of oppression and aggression that maintains the status quo, and therefore, white privilege.

As Terese Jonsson argues, quoting feminist critical race scholar Sherene Razack: “Liberatory work rooted in an understanding of different oppressive systems as entangled and dependent upon each other requires a shift of focus, away from innocence and towards complicity. Recognizing one’s complicity within oppressive systems is not about wallowing in guilt, but about developing an acute understanding of precisely where and how we are positioned within oppressive structures, and how we can use the power that we are afforded within these structures to work towards undoing them” (“Whiteness, Innocence and Complicity: Lessons from anti-racist feminisms”, 2021).

During the pandemic, 2020 brought revolt and activism to the streets. The extraordinary scale of the protests triggered by George Floyd’s assassination by American police in Minneapolis promoted public conversations on whiteness, white privilege or racism, bringing media attention and coverage. Old appeals made to institutions were revitalised. The state, the police, education, media outlets, etc. were called upon to own up to, respond and correct the historical damage, the structures of oppression and privilege. Black bodies occupied public space demanding representation, restitution, withdrawal, decontextualising. The most symbolic expression of these protests that happened all over the place, from the US to Britain, from Belgium to New Zealand, was the disfiguring and knocking down of some statues of icons of the discoveries, like Christopher Columbus, of imperialist governments like Winston Churchill, Leopold II of Belgium, or Edward Colston, a member of the British parliament and a slave trader. When demonstrators felled these statues of colonisers, explorers or imperialist heroes, it was a cry of rebellion that reignited conversations about the history of the slave trade and colonisation in Europe and America with unmatchable strength, giving hope that finally structural racism would be recognised as something that is still very real and violent for a considerable number of people. These debates are not new, they are just being heard with renewed strength.

5. Body is Present

Verbs of the day: to redo, restore, reframe, redefine, present, represent.

|

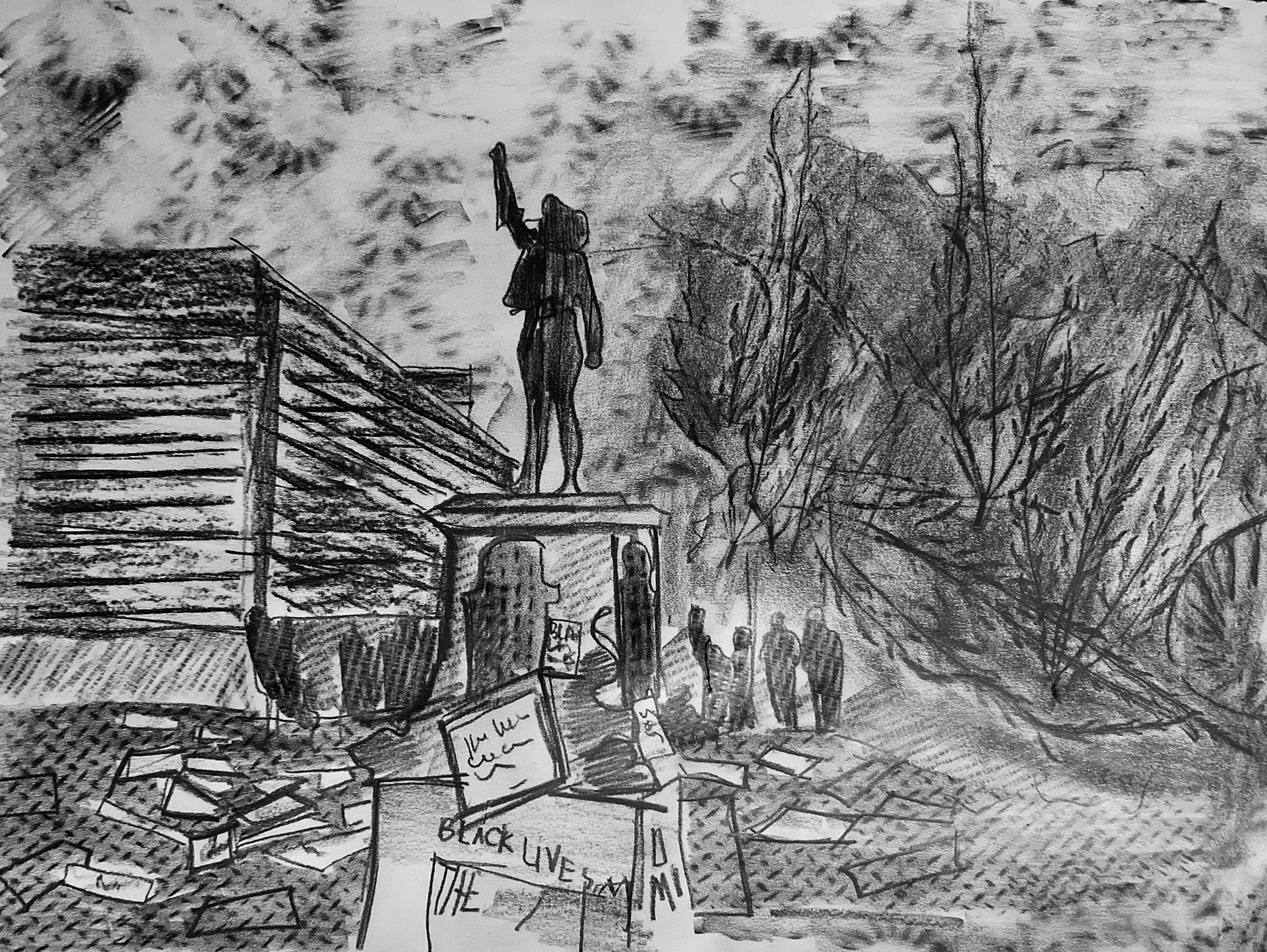

The fall of Edward Colston’s statue, Bristol, 2020. Drawing by Susana Gaudêncio, courtesy of the artist. |

|

I question, how can underrepresented communities be part of re-signification processes? How can they review and recognise themselves in the symbols of public space, in the toponyms of the streets where they walk everyday? How can they develop counter narratives and strategies of re-contextualisation? What should we do to patriarchal or colonial monuments that are offensive to them? Dismantle, destroy, relocate, archive? Can art have some relevant role in all of this? How can we adequately include and honour the African diaspora and the victims of colonialism? How can we eradicate racism in the politics of European colonial remembrance?

Paul B. Preciado, a transsexual philosopher, curator and activist, comments apropos of museums and pedestals: “Let the museums remain empty and the pedestals bare. Let nothing be installed upon them. It is necessary to leave room for utopia regardless of whether it ever arrives. It is necessary to make room for living bodies. Less metal and more voice, less stone and more flesh” (“When statues fall”, 2020, artforum.com).

On the morning of 7 June 2020 in Bristol, anti-racist demonstrators used ropes to pull down the bronze statue of Edward Colston, a prominent slave trader from the seventeenth century and a controversial figure in the city. Colston was a member of the Royal African Company, which transported about 80,000 men, women and children from Africa to the Americas to be sold and enslaved. Before dying he offered his wealth to different charitable institutions, so his legacy is still quite present in the streets, monuments and buildings of Bristol. The statue was later dragged through the streets of Bristol and thrown into the dock water. Afterwards, the empty pedestal was used as a stage and improvised support for demonstrator’s written statements.

|

Jen Reid (Black Lives Matter activist) on top of the pedestal of Edward Colston’s statue, Bristol, 2020. Drawing by Susana Gaudêncio, courtesy of the artist. |

|

On that same day, Jen Reid, a Black Lives Matter activist, climbed up and occupied the empty pedestal; an action that is as subversive as it is emancipatory. The moment is registered in an image that reached all corners of the world. This act turned into image is related in a way to another family of photographs titled Redefining the Power (2011), which is from the project Homem Novo [New Man] (2011–2012) by Angolan artist Kiluanji Kia Henda. The project examines who is represented in the public sphere and the power associated with it. Living Angolan people stand on pedestals from the colonial past of Luanda that were left empty. Through these images, Reid and Kia Henda occupy a place of representation previously left vacant.

On 15 July 2020, the city of Bristol woke up to a new reality. In the place of Colston there was now a statue of Jen Reid replicating the gesture of the raised fist on top of the plinth, created by British artist Marc Quinn. The black resin statue, titled A Surge of Power, was intended as a temporary intervention to maintain the momentum of debates about racism. Quinn states that the image of Reid standing on the pedestal inspired him. He contacted the activist through social media and then Quinn ended up collaborating with her in the making of the statue. Reid said on the episode:

“When I was stood there on the plinth, and raised my arm in a Black Power salute, it was totally spontaneous. […] I didn't even think about it. It was like an electrical charge of power was running through me. […] This sculpture is about making a stand for my mother, for my daughter, for black people like me” (“Jen Reid: Statue of Black Lives Matter protester appears on Colston plinth”, 2020, bbc.com).

But Quinn’s statue produced some opposition. For some, it was seen as an act of active alliance and empathy in the anti-racist fight, for others – namely black British artist Thomas J Price – it was a gesture of appropriation from a white, cis man: “I think it would be far more useful if white artists confronted ‘whiteness’ as opposed to using the lack of black representation in art to find relevance for themselves. […] I can understand the initial positive reactions of those looking to address the lack of visible diversity within public sculpture and gestures towards allyship, but in my opinion Quinn has literally created the votive statue to appropriation.” (“Allyship or stunt? Marc Quinn’s BLM statue divides art world”, 2020, theguardian.com)

Going back to the Portuguese context, specifically public space in cities: in Porto, we are still living under a policy of exclusion, a continuation of a glorified memory of colonial times, instead of memories of the subaltern, as exemplified by the project Vestígios Coloniais: Mapeando o Porto [Colonial Remnants: Mapping Porto] by Interstruct Collective. This collective based in Porto, made up of members with diverse cultural origins, aims to activate a debate about interculturalism through projects of artistic creation, curating, mediation and social practices, valuing “inclusion, empathy and self-reflection as the basis to break ideologies and adverse stereotypes” (from their website: interstructcollective.com). Vestígios Coloniais: Mapeando o Porto [Colonial Remnants: Mapping Porto] is an interactive cartographic device, available online. It is an additive collective archive of photography and text, open to external contributions. The work records marks of colonialism and xenophobia that still persist today in the experience of walking and inhabiting the city. As an example: the statue of Conde Ferreira – a slave merchant; the Café Império; the little black people from Japan; the Monument for the Portuguese Colonising Effort at the Império Square; the many porcelain frogs inside shops intended to keep the Roma community away, a possible threat to business, etc.

I think it would be far more useful if white artists confronted ‘whiteness’ as opposed to using the lack of black representation in art to find relevance for themselves.

Thomas J Price |

|

In Lisbon, what is being promoted by the politics of memory and forgetting? As mentioned before, the creation of a museum dedicated to the Portuguese Discoveries was part of the plans of the Lisbon Municipality in 2017. In 2018, an open letter was published and signed by historians and social scientists, stating that the names of “Museum of the Discoveries” or the “Museum of the Interculturality of Portuguese Origin” would not be the most appropriate. Around the same time, in 2017, the cultural association DJASS Afrodescendents Association, submitted a proposal for the creation of a memorial to enslaved people, within the remit of the Participatory Budgeting of the city, to be installed in the Campo das Cebolas, a space in the city historically connected to the slave trade, situated in a noble area, next to Terreiro do Paço, where one of the most important ministries of the government is housed – the Ministry of Internal Affairs.

DJASS’s proposal was successful and for the first time an artistic work about the implications of the violence of the Portuguese slave trade will be built. Three afrodescendant artists were invited to present ideas for this memorial: Grada Kilomba, born in Portugal, proposed the design of a boat in silhouette-form, surrounded by 130 benches made of reinforced concrete, which according to the author, could also be seen as graves (a version of this work was presented at maat in 2021); Jaime Lauriano, born in Brazil, wanted to erect a triangular small scale pavilion – a “place of mourning” with a circular bench in its interior – “a place to socialize, a place of communion”; and Kiluanji Kia Henda, born in Angola, chose to represent a plantation with 540 sugar canes, built in black aluminium. Plantação – Prosperidade e Pesadelo [Plantation – Prosperity and Nightmare] was the winning project. The work will present a fictitious sugarcane plantation, each cane measuring three metres. In the middle, there will be a semi-circular amphitheatre, a meeting point that will also present cultural events like music and theatre performances, readings or academic talks. “It will be a place for reflection but also of resistance to racism and the violence of the slave-trade, a process that has consequences in today’s daily life” (esquerda.net).

With this project, Kia Henda makes present the erased memory of slavery, which he considers to be “the central axis in the history of European economic development,” recalling that the sugarcane exploration (white gold) started in the island of Madeira. “To satisfy the need for labour, enslaved people from the Canaries, Morocco, Mauritania and, later, the sub-Saharan Africa were taken to the island. After this, black people in the 17th century made up 10% of the population of Portugal. The port of Lisbon became one of the biggest ports of the slave trade in the world”.

This will be an opportunity to confront the hegemonic narrative of the history of Portugal, where still today the descendants of enslaved people suffer from racism. How can we transform this legacy into something positive? How big can that transformation process be? To recognise the past, to tell the stories of how black people resisted, to analyse the legacies of that undertaking. Portuguese sociologist

Cristina Roldão believes that it is necessary to build places for the afrodescendant community: “[…] even though they are important, memorials and interpretation centres aren’t enough, it is necessary that close relationships with communities of people of colour exist. We must talk about the city, about memory, colonialisms and ethnic-racial segregation in the space of the city. We should demand of the white population that they should take a position, that they deconstruct themselves and that together with black people think and reflect about whiteness, […] bestowing importance to an antiracist education” (online debate, “How to Decolonize our Cities? Goethe-Institut Portugal).

6. Note on Privilege II

Verbs of the day: to occupy, locate, deconstruct, relocate, hold accountable, unify, support, vacate.

Each one of these verbs of the day points towards a path, serving as key words – stances, aims, fears and desires – which then introduce several examples of artistic practice that define distinct, sometimes opposed, uses and representations in public space. The examples presented here show that art can be a fruitful place of critical and political engagement, defying voices of authority, hegemonic thinking and power.

Being part of the Empty Exhibit Cases project, and researching and writing this essay became a personal journey towards being more aware in the process of deconstructing my privilege, my colour, my culture, my position. The process of deconstructing racism is a daily one – a collection of verbs for each new day is necessary – and it must operate at every hierarchical and structural level of society. As an art teacher, for instance, I can restructure my class towards a more inclusive syllabus – other ontologies, other representations and a more horizontal hierarchy between teacher and students.

In “Notes Towards a Politics of Location” (1984), American poet Adrienne Rich tells us that gender, sex, race, social class, education and geographical context locates the body. Through her poetics of dislocation, Rich aims to generate a learning process of the “other,” essential for “the fight for accountability” and the politics of location.

Whether walking in Lisbon, the city I was born in,– or Porto the city I currently live in – I don’t find bodies of black heroines or heroes. How can I move to find “other” bodies? Which limitations and possibilities does that movement bring? How can I dismantle the white privilege and racism inherent to my body and consequently be permitted to be an ally in the construction of other representations?

Amid privilege, there is the belief that one occupies a place in the centre, and this should imply the acceptance of lapses in knowledge and an understanding about the rest of the world, which occur from that positioning, in the sense that “all privilege is ignorant at the core.” I aspire to vacate the centre.

Susana Gaudêncio is an artist, teacher and researcher, living and working in Porto (Portugal). Since 2000, she has exhibited her work in Portugal and internationally, in institutional and independent spaces and is represented in several public and private collections. Her latest projects have integrated concepts such as the utopian impulse, heterotopia, language, the practice of walking and artistic production as a platform to find new possibilities for problematizing utopia as a critical and political device of everyday life. She has a degree in Painting (FBAUL), Master in Fine Arts (MFA - CUNY), PhD in Fine Arts - Audiovisuals (FBAUL). Currently, she is a researcher at Lab2PT and teaches at EAAD (University of Minho).

Empty Exhibit Cases gathers three cisgender white women working in the arts, Susana Pomba, Susana Gaudêncio and Maribel Mendes Sobreira, on their way to become life-long anti-racist and effective allies, as artists, teachers, researchers, curators, historians, writers, or authors. The project delivers a group of essays (in diary mode), that might be hybrid in form, and attempt to dissect various questions and struggles, all in the context of the daily personal and professional lives of the three participants. They will also engage in conversation with activist groups, scholars, or cultural agents.

Based on diary-keeping as a form of writing, the Mode Diaries initiative creates a field of interpretative potentialities within the context of maat Mode 2020, a public, experimental and participatory exhibition and activity programme under the motto “Prototyping the museum”. This is the scope that justifies and enables the twisting of the meaning commonly attributed to the term “diary” by transforming what’s individualised into collective, private into public, singular into plural, etc.