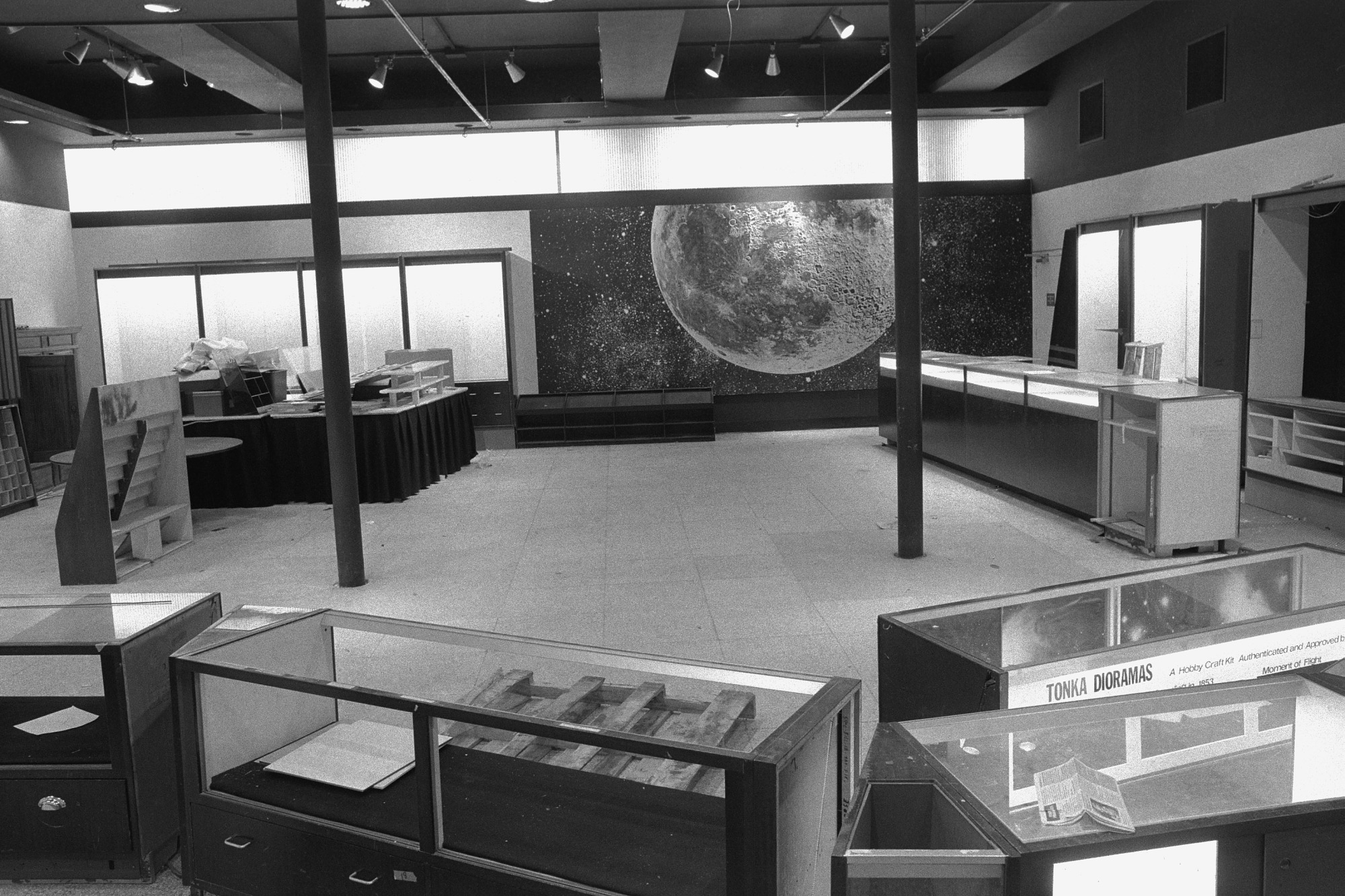

Empty exhibit case at the United States National Museum, now known as the Arts and Industries Building, 1880s, USA. © Smithsonian Institution Archives. Image #SIA-75-11093-16A.

On 27 February 2021, we had a (private) Zoom conversation with Teresa Fradique, Professor of Social Sciences at the School of Arts and Design (ESAD.CR–IPLeiria, Portugal), among other universities. Moderated by Susana Gaudêncio, participants included Susana Pomba and Maribel Mendes Sobreira. This is the second of a group of three conversations included in Empty Exhibit Cases, a project that gathers three cisgender white women working in the arts, on their way to become life-long anti-racist and effective allies as artists, teachers, researchers, curators, historians, writers or authors.

Susana Gaudêncio

How did your professional life unfold? How did you find the objects of your study?

Teresa Fradique

First of all, thank you for inviting me and for this format, which I find wonderful: an informal conversation to exchange ideas, which then has a chance to be revised and rethought in the process of transcribing. My path has always been connected to anthropology, and I went through the typical academic “ladder” of graduate, master’s and then doctorate. When transitioning to a master’s degree, I started to be very interested in possible connections between anthropology and art. My relationship with anthropology tends to be epistemological, if I can put it that way, contrary to other colleagues from my generation that made a direct and complete turn– to poetry, film, fine-arts, etc. Even though I have always favoured this dialogue with other areas, I ended up keeping myself fixed to this “anthropological identity”, for lack of a better term, searching for possible contaminations so I could think methodologically within this subject. In this sense, I kept asking myself what could anthropology gain with paying attention to other means of practice, knowledge and analysis of the real. For my master’s degree, I chose rap and hip-hop, emerging movements in the mid 1990s. As I stated before, my relationship with that universe was at first epistemological. Besides doing “field work”, as we say in anthropology, I used research to try to understand what would happen if we brought into the subject a world that is apparently anthropological – because it was led by young people living in the suburbs of Lisbon in a time when urban anthropology had strength in academia (at least in ISCTE, where I was a researcher) – but more important than that, one that allowed the analysis of an autonomous cultural production – hip-hop. My interest lay in the way hip-hop defied anthropological canons, precisely because it was started by young people and therefore it didn’t have the conventional weight of “tradition”. Also around this time, ESAD.CR (Upper School of Arts and Design Caldas da Rainha) was setting up its courses, having gone through a participatory process where students took a stand and made change happen. In this interesting and tumultuous moment of thinking which direction an art school should take, some of the younger teachers that were responsible for new hires had had the art anthropologist José António Fernandes Dias as a teacher, and as a result had not only great empathy with his work and what he taught, but had also learned to see a clear path into the contemporary through anthropology, one that they couldn’t find in other subjects and domains. At the time, they thought that this subject should be essential when teaching arts and so, the subject of anthropology came to be mandatory in the curriculum. That’s how I started at ESAD.CR. Later, I found myself quite involved with the theatre course and I did my doctorate on performance. Again, performance is a study object that sits in the crossing of subjects, as I am always trying to understand how I can bring knowledge, a specific procedure and a group of research practices that belong to the arts into anthropology. My doctorate thesis was on theatre directors who chose non-professional actors in search of a certain “authenticity” that translates into a certain aesthetic quality that someone who is not prepared for the stage can have.

Currently, at school, I am a sort of anthropologist “always on call”, weaving a kind of mesh that reaches several different areas. I am more present today on courses like design and fine arts, but I have basically taught every course in the school. And I always bring an anthropologic perspective to these different classes and students. A practice that in the past was clearer, maybe more literal, and that has now become a lot more complex, problematic and interesting – bringing a humanistic and relativist dimension, and an attention to cultural diversity in general, not in the exoticising sense that anthropology seems to produce when called upon by other subjects, but most of all working with students on their ability to escape comfort zones and think about non-normative categories. During many years, when the subject of anthropology was invoked, it was around the idea of multiculturalism and interculturalism. Today, this calling is much harder – more difficult I mean – and a lot more complex. It concerns bringing to a particular context, the classroom, discussions about the place of speech, the power of visibility and about who is kept invisible, about being aware from which perspective the world is designed, in the case of design, or from which perspective it is interpreted and represented, in the case of the fine arts.

Susana Gaudêncio

How urgent are the strategies of reparation and restitution in Portugal, and also visibility and invisibility. Why haven’t we done it yet? At an institutional level, in museums and archives, and as citizens and academics. What can we do? Maybe before that we should admit to the errors of colonisation, which we haven’t done yet.

Teresa Fradique

After finishing my doctorate, I started to understand that I had to focus my research on a series of worlds I had already approached in class, but had never considered as a study object. Namely, how close ESAD.CR is to a group of existing cultural institutions with collections and stores, which have not been put into question by projects within the school or other broader discussions and research. I recently wrote a text that has as a starting point the Malhoa Museum and some pieces in its collection. It thinks about regimes of visibility and invisibility relating to those same works of art. How is it possible that a museum functions sometimes more as a device of invisibility than the opposite, which is what it’s supposed to do? In particular, within the exhibition system I studied, how can a display end up “hiding” a group of characteristics that are part of the nature of the piece, but that cannot be accessed? The museum was created in 1933 – a year that marks the beginning of the New State regime in Portugal – as a contemporary art museum, and ended up, in part, because of those circumstances, becoming a container of sorts that received pieces connected to the regime. Today, one of my personal struggles has precisely to do with that reflection and discussion (analytical and political) about the processes of visibility and invisibility and that is very much connected with your Empty Exhibit Cases project and with this group of privileged white women discussing that metaphor. I have been thinking more and more about the place from which we can approach these questions that Susana [Gaudêncio] asked, even to do with reparation, etc. The work around the Malhoa Museum also thinks about how privileged people like us can become more invisible but now in a productive, empathetic and conscientious sense. How can we open space in our research to think and discuss uncomfortable themes – like the work of artists connected to the New State regime, for instance. I think that this is a relevant question when faced with the sort of paradox that brings us together in this project. We want to think about this – “how to become life-long anti-racist and effective allies”, like you put it – we know this path is important, we have to think about what is our role in it, but we also have to think that because we are privileged, we are occupying space in this discussion. And that, sometimes, through our production, we might be reducing the space of someone that is under-privileged who has a point of view we should, imperatively, give visibility to. In this sense, those of us that are on this side of the discussion should take on the role of studying our own culture. With this I mean, to analyse the contexts and processes of reification and of perpetuation of white supremacy and our privilege. This will allow us to look in the mirror and make a contribution to prepare the soil for change. That is why I decided, for instance, at Malhoa Museum, to look at the work of Eduardo Malta, a terrible character. It’s in this place of discomfort and reflection about the consequences of privilege that I situate myself when I think about restitution and reparation. The work around the restitution of objects displaced in a colonial context is important, but a study on the cultural devices that created the archives and museums involved in these same systems of circulation, cataloguing and exhibiting should be done at the same time. And we have to work on these matters within the places we occupy professionally, as curators, for instance. This discussion will clash with the value given to the objects themselves, namely when they reach the category of work of art, which is deeply rooted in Western culture. The way we give value, produce, legitimise and show a work of art is very specific in the Western world. If we summon other ontological universes, the paradigm can be entirely different. In this restitution and reparation process, and in the work with memory one has to do, the big question is, if people who occupy the place of whiteness are prepared to face their own “creatures”, in other words, face those devices, whether the museum or the concept of art itself. And that work is fundamental, because if we don’t do it it will be very difficult to consolidate critical processes, as we have seen. As Susana [Gaudêncio] was saying, it will allow us to own up to the error of colonisation.

In this restitution and reparation process, and in the work with memory one has to do, the big question is, if people who occupy the place of whiteness are prepared to face their own “creatures”, in other words, face those devices, whether the museum or the concept of art itself.

Teresa Fradique

Susana Pomba

Does a museum of ethnography make sense? How do you dismantle a museum?

Teresa Fradique

As a device, the ethnographic museum contains processes of some exercise of violence on objects of use that traditionally make up its collections, mainly the ones of ritual use, in the way it shifts them and submits them to new ways of exhibiting. In my view, anthropology should contribute, as it has always aimed to do, new methods of analysis that allow us to question to what extent we are ready to look at our inherited paradigms, at the way we collect and exhibit, including our own definition of art object. If, in other times, anthropologists seemed to be almost isolated protagonists of this process, today we have realised that anthropology couldn’t complete this process and that the discussion is much more complex, fortunately. There are many more voices coming into the scene, claiming a position that builds a vision of the world that bases itself in traditions that were once erased and forgotten.

Two very interesting positions of analysis are gaining traction: on the one hand, Amerindian thought with voices that are already present in our public sphere like Ailton Krenak or Eduardo Viveiros de Castro, that, among others, reveal to us the existence of an alternative philosophical system that builds another vision of the world. On the other hand, we have thinkers of the African world like Achille Mbembe. Let me read you an excerpt of his text “Anti-Museum”, which can help us think about the Ethnology museum: “What the history of Atlantic slavery urges us to do is thus to found a new institution – the anti-museum. The slave must continue to haunt the museum such as it exists today but do so by its absence. It ought to be everywhere and nowhere, its apparitions always occurring in the mode of breaking and entering and never of the institution. This is how the slave’s spectral dimension will be preserved. This is also how facile consequences will be prevented from being drawn from the abominable event of the slave trade. As for the anti-museum, by no means is it an institution but rather the figure of another place, one of radical hospitality” (→ 1) When I enter the ethnographic museum, I situate the discussion from a very concrete and very circumscribed device because it is a cultural product of which we are part. How do we deal with it? I feel it’s not by refusing to enter but by bringing inside the museum a practice of resistance. We have to go in, but not by resting, and even less by discarding, this permanent problematisation.

Susana Gaudêncio

Are you saying we still have to do it because we still have to learn how to proceed with the deconstruction process?

-

(1) Achille Mbembe,“Anti-Museum,” in Necropolitics, trans. Steven Corcoran (Durham and London: Duke University Press, 2019), 172.

Teresa Fradique

This deconstruction is only possible by continuing to do what we do – art, philosophy, research – but much more permeable to a way of proceeding that has to let other visions in. Still Mbembe, in the book he launched last year, Brutalisme (2020), evokes the vision of brutalism in architecture as a political category to think the contemporary world characterized by planetary "combustion" (→ 2). One of his claims is that life at the extremes will become the norm, that is, our shared common condition. And he recalls that this experience of the limits has been lived earlier by some more than others and that, above all, the South has for centuries lived out of the “unfeasible”. Mbembe closes the introduction of the book by returning to the subject of the “anti-museum”, challenging us to think about the limitations of institutional space, like the ethnographic museum, to make that reconstruction you are referring to. He says: “More and more, it seems likely that what was taken has no price and can never be returned to us. The absence of any possibility of restitution or restoration perhaps signals the end of the museum, understood not as an extension of a cabinet of curiosities, but as a figure par excellence of humanity's past, a past it would be a sort of direct witness. There would be nothing left but the anti-museum, not a museum without objects or a fleeing address of objects without a museum, but a sort of barn of the future whose function would be to shelter what is excepted to be born but hasn’t arrived yet.” (→ 3) One of the greatest challenges Mbembe gives us is to seek out geographies which, in the contemporary condition, are “potency in reserve” (puissance en réserve) and allow us to activate “events for thought” (événements pour la pensée). Geographies that concentrate an “unviable” living experience, a condition that is spreading worldwide, as we said before. A completely eroded soil, where a seed falls. What happens when the seed falls in the desolated soil? asks Mbembe. It’s from these proposals that we can think the whole, along with these thinkers of the human condition, and not just as thinkers of the (de)colonial, as they sometimes are seen. The growing presence of Amerindian ontologies, like the proposals that Ailton Krenak brought to Maria Matos Municipal Theatre in 2017 and later in the published book, Ideas to Postpone the End of the World (2019), are also very important and useful for us to (re)finding our place. When Krenak asks “are we really a humanity?” (→ 4) he is referring to this idea that we are not all humans in the same way, or better, that we don’t live our humanity in a universal way. For him, there is a paradigmatic relationship between that idea of unique humanity and the colonial and civilising process, where a more enlightened humanity would “take care” of the other and bring it inside their midst. Krenak says:

“The notion that white Europeans could jump in their ships and go colonizing the rest of the world was based on the premise that there was an enlightened humanity that had to go in search of the benighted humanity and bring those savages into their incredible light. This call to civilization was always justified by the idea that there is a right way of being in the world, one truth, or concept of truth, that has guided the choices made down through history.” (→ 5) Going back to the museum and to your question. When I enter a museum I not only bring epistemological contributions but also our own Western ancestry. And in this sense, what the museum gives me is a museum within a museum because, before anything else, it is the materialisation of a specific device of relationship with certain types of objects and what they represent in symbolic terms. When Mbembe tells us, “There is no price, there is no possible restitution”, what he is exposing is the impossibility of creating institutions that can dismantle the violence of other institutions if they keep using the same paradigms. In 2019, I watched Matthias De Groof’s documentary Palimpseste du Musée d’Afrique (2019), at Culturgest in Lisbon, about the Royal Museum for Central Africa, in Tervuren, Belgium. Since then I have discussed it with my students (masters in cultural management) that are always very surprised with the cases and objects being dismantled, sometimes actually broken: “they really are destroying the museum,” they say, astonished but also harbouring conflicting feelings. Besides this more startling side, the documentary has a very interesting part (maybe more interesting, I would say) that focuses on meetings between specialists, museologists, curators, historians and well-known figures that represent the countries from where the objects in the museum collections originally came from. The level of complexity reached in the discussion and reflection between the several participants shows that the renovation of the museum, based on an attempt to eradicate every prior colonial crime, by creating a new museum with the name Africa Museum (that opened in 2018), couldn’t remove the paradigm with which it was founded. Ultimately, it is the building itself – the result of the 1897 Brussels International Exposition – that materialises the legacy of a brutal colonial regime. The transformation and the changes of displays or exhibition narratives are not enough to make that dismantling from the inside, and the museum workers also seem to not be able to follow the scale of complexity of that dismantling that will allow the renovation (and the restitution).

-

(2) “Par brutalisme, je fais donc référence au procès par lequel le pouvoir en tant que force géomorphique désormais se constitue, s’exprime, se reconfigure, agit et se reproduit par la fracturation et la fissuration.” Achille Mbembe, Brutalisme (Paris: Éditions La Découverte, 2020), 9-10.

-

(3) Ibid, 29. “De plus en plus, il est probable que ce qui nous est pris sera sans prix et ne pourra jamais nous être restitué. L’absence de toute possibilité de restitution ou de restauration signera peut-être la fin du musée, entendu non pas comme l’extension d’une chambre de curiosités, mais comme la figure par excellence du passé de l’humanité, un passé dont il serait comme la butte témoin. Ne resterait plus que l’antimusée, non point le musée sans objects ou la demeure fugitive des objects sans musée, mais une sorte de grenier du futur dont la fonction serait d’accueillir ce qui doit naître, mais n’est pas encore là.”. Working translation into English by Teresa Fradique.

-

(4) Ailton Krenak, Ideas to Postpone the End of The World, trans. Anthony Doyle (House of Anansi Press Inc., 2020). He comes back to this discussion in his most recent book A Vida não é útil [Life Isn’t Useful] (2020).

-

(5) Ibid.

We have to go beyond being worn out by indignation.

Teresa Fradique

Susana Gaudêncio

So, you think that it should be a group with only detached agents? Maybe activists can be freer.

Teresa Fradique

Yes, surely. But I also think that this work is a mesh work. While textbooks are not decolonised, while ethnic-racial data census isn’t collected, while we don’t have a system of quotas to access higher education for students and teachers (one of the most important struggles), these localised and circumscribed tasks will always be unfulfilled.

Susana Pomba

But when you talk about mesh, is that what you mean? A series of things that have to be done at the same time?

Teresa Fradique

Yes, different platforms that act simultaneously, and that cross each other at certain moments, and then later go back to their own path. And from these lines and knots they create, a mesh is formed. A mesh that gives consistency, coherence and the possibility of true transformation. And for that to happen one of the things we have to instigate is meetings. When I say mesh, I am not saying it’s the most effective process, but it’s how things happen, and it might become more fruitful if we know how to weave it.

Maribel Mendes Sobreira

Because even if we change textbooks, educational programmes, teachers remain the same, which means that internal mechanisms and the ways of thinking of some prejudiced teachers don’t change.

Teresa Fradique

We have to prepare for that process, we have to go beyond being worn out by indignation. Just by itself, indignation is of little use. There’s no point in saying, “I won’t go in a museum, because I am outraged,” no, we go in to resist, to deconstruct, to keep looking in the mirror and to keep thinking.

Teresa Fradique graduated in Anthropology at ISCTE – University Institute of Lisbon (1994) and has an MA in Anthropology – Heritage and Identities (1999) from the same institution and holds a PhD in Anthropology – Ritual and Performance from Universidade Nova de Lisboa (NOVA FCSH). Professor of Social Sciences at School of Arts and Design (ESAD.CR-IPLeiria) since 1999 and Invited Professor at the Department of Anthropology NOVA-FCSH (2011-2012) and Postgraduate Tutor in Artistic Practices and Community at ESMAE-IPP (2014-2018). Former President of the Scientific Board and currently President of the Representative Board at ESAD.CR-IPLeiria, she is also President of the Assembly of the Portuguese Anthropology Association (APA). She is a researcher at the Center for Research Network in Anthropology (CRIA) and coordinator of the Center for Visual Anthropology and Art (NAVA) of CRIA. Specialist on urban cultures, anthropology of art and design, performance and pos-colonial studies, Teresa Fradique published “Fixar o movimento: Representações da música rap em Portugal” (Portugal de Perto/D. Quixote, 2003) and co-edited with Paulo Raposo, Vânia Cardoso and John Dawsey “A terra do não-lugar: diálogos entre antropologia e performance” (Florianópolis, UFSC, 2013). She has also published several papers and book chapters mainly on urban cultures, performance and visual anthropology. She also works as a consultant in the critical monitoring of artistic projects in the field of performing and visual arts.

“Empty Exhibit Cases” gathers three cisgender white women working in the arts, Susana Pomba, Susana Gaudêncio and Maribel Mendes Sobreira, on their way to become life-long anti-racist and effective allies, as artists, teachers, researchers, curators, historians, writers, or authors. The project delivers a group of essays (in diary mode), that might be hybrid in form, and attempt to dissect various questions and struggles, all in the context of the daily personal and professional lives of the three participants. They will also engage in conversation with activist groups, scholars, or cultural agents.

Based on diary-keeping as a form of writing, the Mode Diaries https://www.maat.pt/en/event/mode-diaries-introduction initiative creates a field of interpretative potentialities within the context of maat Mode 2020 https://www.maat.pt/en/maat-mode-2020, a public, experimental and participatory exhibition and activity programme under the motto “Prototyping the museum”. This is the scope that justifies and enables the twisting of the meaning commonly attributed to the term “diary” by transforming what’s individualised into collective, private into public, singular into plural, etc.