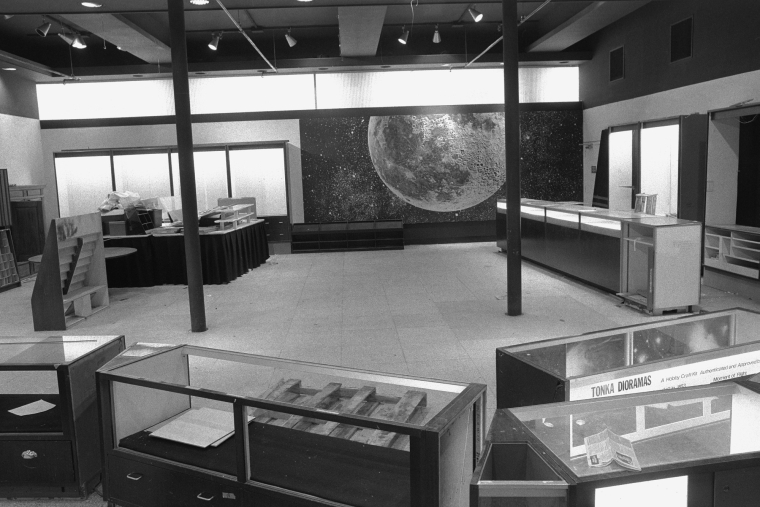

Empty Exhibit Cases [Can you jot that down?]

While we wait in silence for that final luxury of fearlessness, the weight of that silence will choke us.

— Audre Lorde

[Hereby follows a list of all the exhibit cases, plinths, and other objects available]

“Women of today are still being called upon to stretch across the gap of male ignorance and to educate men as to our existence and our needs. This is an old and primary tool of all oppressors to keep the oppressed occupied with the master's concerns. Now we hear that it is the task of women of colour to educate white women – in the face of tremendous resistance – as to our existence, our differences, our relative roles in our joint survival. This is a diversion of energies and a tragic repetition of racist patriarchal thought.”

— Audre Lorde, “The Master's Tools Will Never Dismantle the Master's House” (1984).

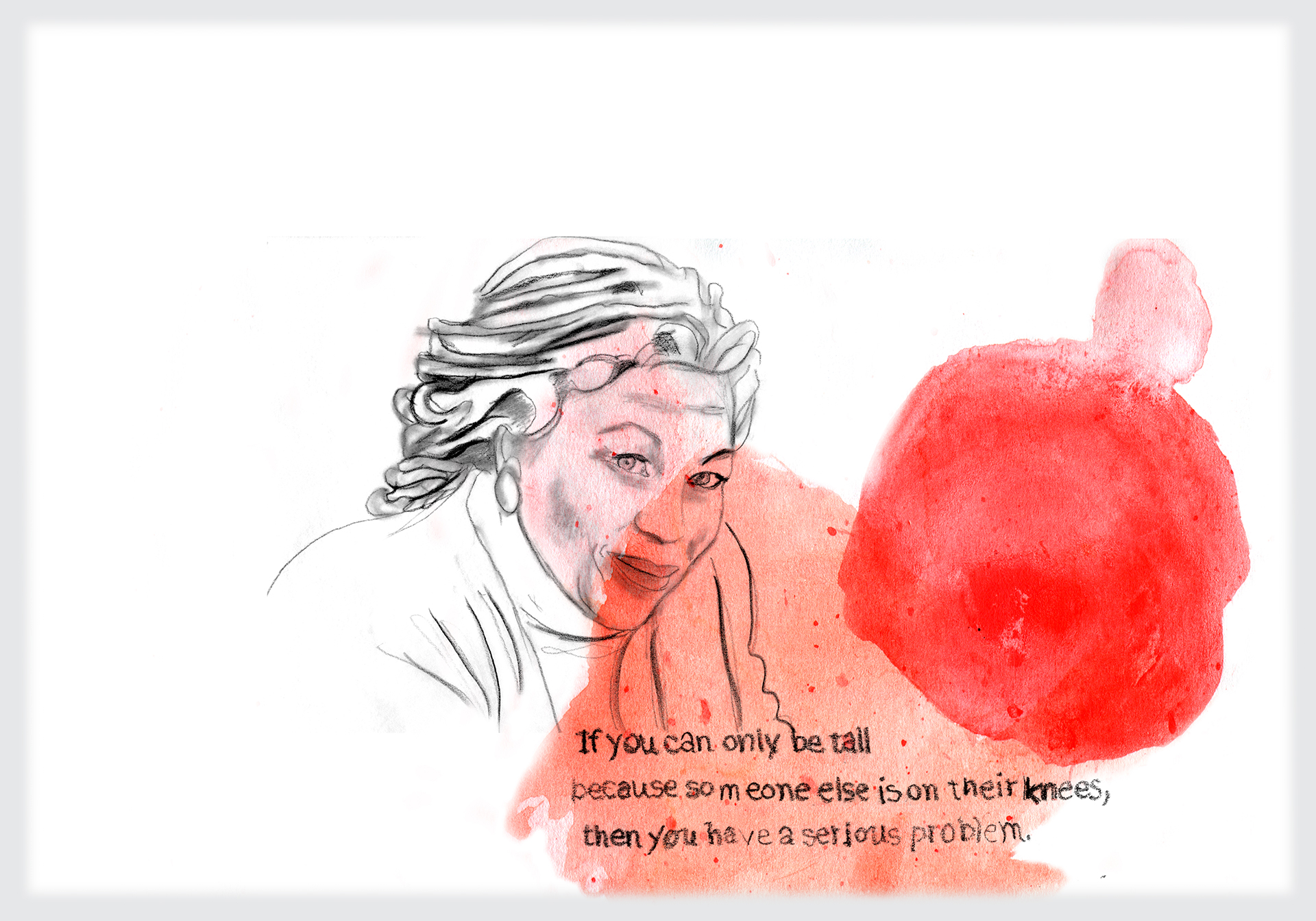

“If you can only be tall because someone is on their knees, then you have a serious problem. And my feeling is that white people have a very, very serious problem, and THEY should start thinking what THEY can do about it. Take me out of it.” And Charlie Rose, the interviewer, a white man, asks: “Then give white people some FREE advice”. Toni Morrison chuckles, and replies, “It’s all in my books.”

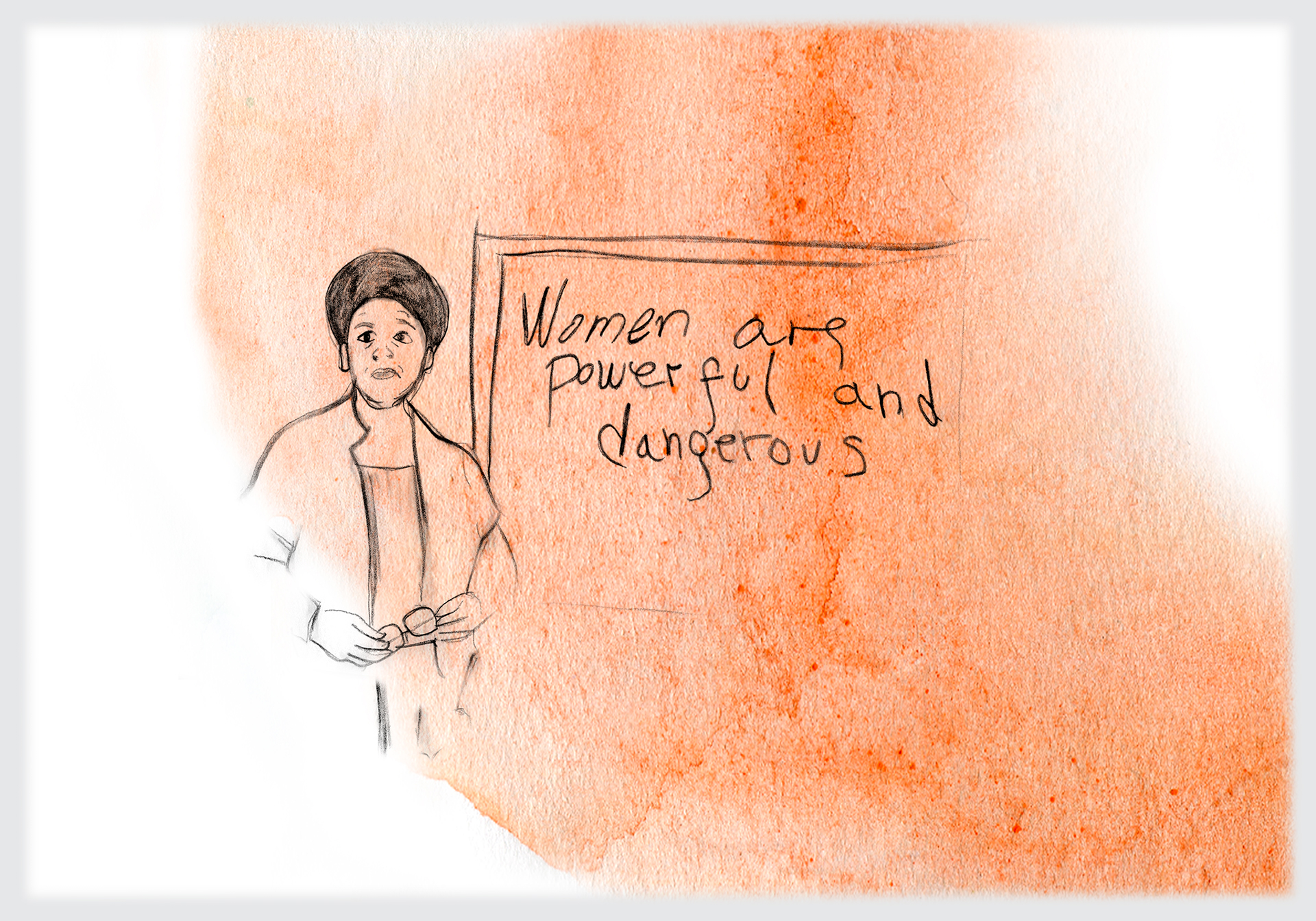

In 1983, bell hooks completed her doctorate in literature at the University of California. Her dissertation was on author Toni Morrison.

[This place has been locked for some time. Write a short report]

“White feminism is a politics that engages itself with myths such as ‘I don’t see race’. It is a politics which insists that talking about race fuels racism – thereby denying people of colour the words to articulate our existence.”

— Reni Eddo-Lodge, Why I’m No Longer Talking to White People About Race (2017).

“At the same time, white feminists, that had started their fight against sexual domination, in part inspired by the American Anti-Slavery Society, will end up by excluding black women from their conventions. The black activist Sojourner Truth stood up to white women and asked, ‘Ain’t I a woman?’”

— Paul B. Preciado, An Apartment on Uranus (2020, English edition).

[Dust gathers, even if you set white sheets over every case, chair, table, painting]

“It is a particular academic arrogance to assume any discussion of feminist theory without examining our many differences, and without a significant input from poor women, Black and Third World women, and lesbians.”

— Audre Lorde, The Master's Tools Will Never Dismantle the Master's House (1984).

“In ‘The Second Sex’, Beauvoir says: ‘If the “question of women” is so trivial, it is because masculine arrogance turned it into a “quarrel”; when people quarrel, they no longer reason well.’ And I update that relating it to black women: if the ‘question of black women’ is so trivial, it is because the arrogance of white feminism turned it into a ‘quarrel’, and when people quarrel, they no longer reason well.”

— Djamila Ribeiro, Quem Tem Medo do Feminismo Negro? [Whose Afraid of Black Feminism?] (2018). Translated from the Portuguese.

[No one is available to proceed with the installation]

“In addition to this, it is very important that white women in the women’s movement examine the ways in which racism excludes many black women and prevents them from unconditionally aligning themselves with white women. Instead of taking black women as the objects of their research, white feminist researchers should try to uncover the gender specific mechanisms of racism amongst white women. This more than any other factor disrupts the recognition of common interests of sisterhood.”

— Hazel V. Carby, “White woman listen! Black feminism and the boundaries of sisterhood” (1982). Read the complete text.

[Uninstalling has been left unfinished]

Isabella Hardenburg, enslaved person, carried a name given by her “master”. She prayed to God for an appropriate name, and the name “Sojourner” was whispered to her. She added “Truth”, because besides being a traveller, the suffragist wanted to preach the truth to all.

[Before you arrive, should we temporarily fill these cases with our labour]

“I have come to see white privilege as an invisible package of unearned assets that I can count on cashing in each day, but about which I was ‘meant’ to remain oblivious. White privilege is like an invisible weightless knapsack of special provisions, assurances, tools, maps, guides, codebooks, passports, visas, clothes, compass, emergency gear, and blank checks.”

— Peggy McIntosh, White Privilege and Male Privilege: A Personal Account of Coming to See Correspondences Through Work in Women’s Studies (1988).

“In proportion as my racial group was being made confident, comfortable, and oblivious, other groups were likely being made unconfident, uncomfortable, and alienated. Whiteness protected me from many kinds of hostility, distress, and violence, which I was being subtly trained to visit in turn upon people of colour. … The kind of privilege that gives license to some people to be, at best, thoughtless and, at worst, murderous should not continue to be referred to as a desirable attribute.”

— Peggy McIntosh, White Privilege and Male Privilege: A Personal Account of Coming to See Correspondences Through Work in Women’s Studies (1988).

“Because I am not capable of cutting myself to pieces. I’m not capable of cutting away my blackness in order to support feminism that views the needs of women of colour as divisive inconveniences. I’m not capable of cutting away womanhood in order to stand by black men who prey on black women. I’m a black woman, each and every minute of every day – and I need you to march for me, too.”

— Ijeoma Oluo, So You Want to Talk about Race (2018).

[It was all built in-house.]

“Intersectionality aims to provide theoretical and methodological tools to deal with the structural inseparability of racism, capitalism, and cis-hetero-patriarchy – producers of identity paths in which black women are repeatedly battered by the intersection and overlapping of gender, race, class, and modern colonial apparatus.”

— Carla Akotirene, Interseccionalidade [Intersectionality] (2019). Translated from the Portuguese, available here.

“For black feminist academic Dr Kimberlé Crenshaw, it was her studies in law that led her to coin the now mainstream term. When we met in London’s US Embassy, she told me, ‘That work started when I realised that African American women were . . . not recognised as having experienced discrimination that reflected both their race and their gender. The courts would say if you don’t experience racism in the same way as a [black] man does, or sexism in the same way as a white woman does, then you haven’t been discriminated against. I saw that as a problem of sameness and difference. There were claims of being seen as too different to be accommodated by law. That led to intersectionality, looking at the ways race and gender intersect to create barriers and obstacles to equality.’”

— Reni Eddo-Lodge, Why I’m No Longer Talking to White People About Race (2017).

“Intersectionality or intersectional theory is a proposed approach to analysing multiple forms of discrimination. Not only discrimination according to sex, but also according to race, class, sexual orientation, and religion … Black feminism rose in the US, Brazil, and Europe – in Africa, feminists don’t talk about black feminism, they talk about African feminism … Black feminism is not the only form of feminism that studies black women.”

— Inocência Mata, in “Botequim”, TSF (2020). Translated from the Portuguese, available here.

Inocência Mata is the only black lecturer at the Department of Literature at the University of Lisbon, where she has been teaching Romance literature since 1990.

[Only staff allowed, not open to the public.]

“It was and remains my view that any feminist theory that restricts the meaning of gender in the presuppositions of its own practice sets up exclusionary gender norms within feminism, often with homophobic consequences. It seemed to me, and continues to seem, that feminism ought to be careful not to idealise certain expressions of gender that, in turn, produce new forms of hierarchy and exclusion.”

— Judith Butler, Gender Trouble: Feminism and the Subversion of Identity (1990).

“… the word non-binary has only shown up for most folks in the past 10-15 years, but the experiences have been around forever, we just find new words to talk about it. And actually if we look globally and historically, at ways that societies have viewed gender, most people had a more expansive view of gender before European colonisation set in. And the gender binary was a tool of colonisation and of white supremacy.”

— Maybe Burke (@believeinmaybe), in TikTok).

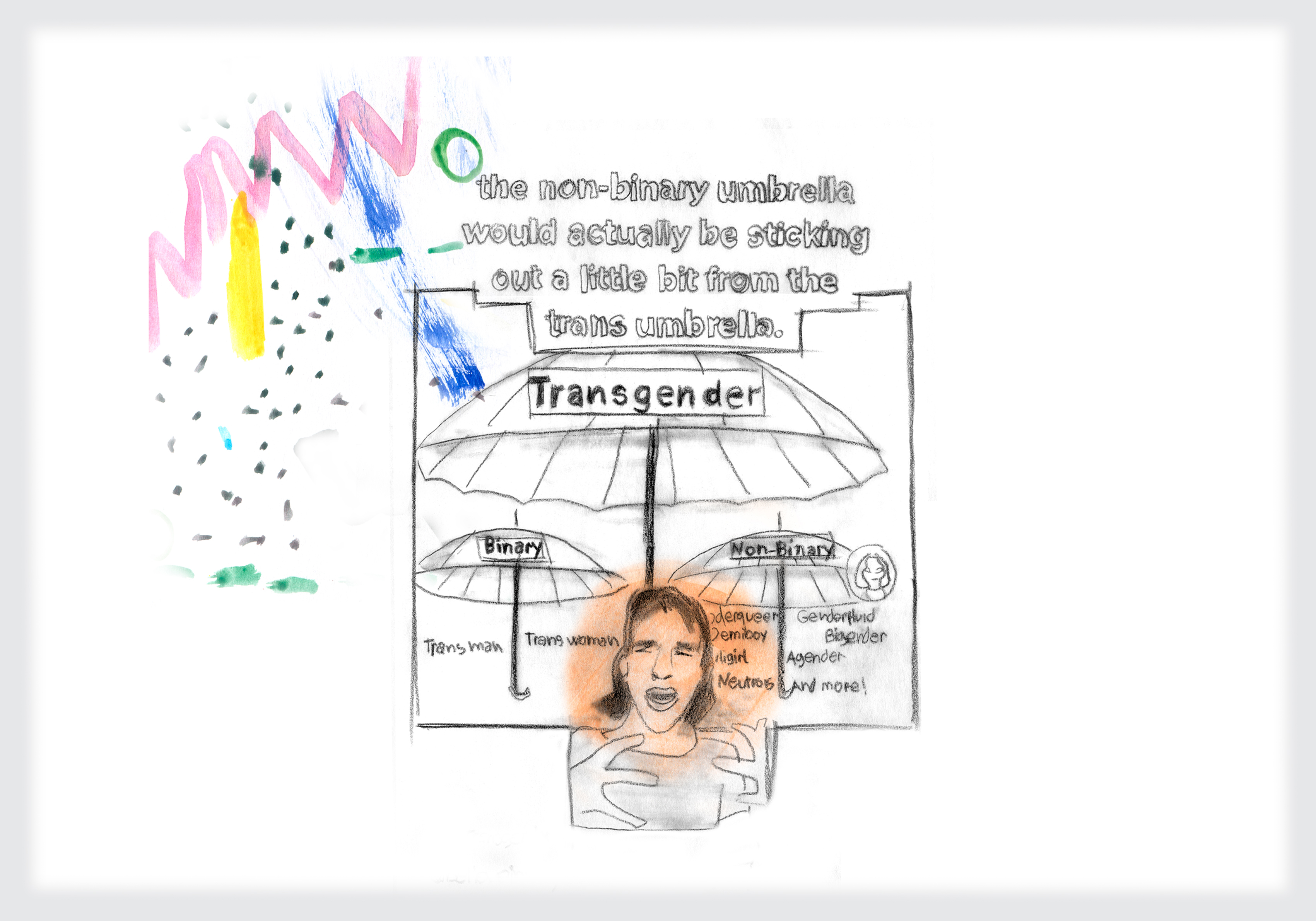

“… If the word transgender means anybody who doesn’t identify with the gender they were assigned at birth, then that means non-binary falls under that category and that umbrella. Not everybody who is non-binary is necessarily going to identify as trans, because a lot of these words are based on comfort and what works best for each person. So if I were to draw this, the non-binary umbrella would actually be sticking out a little bit from the trans umbrella. What I like to say to people who might be non-binary and might not identify as trans, is whenever I am talking about trans communities or gender expansive communities, there’s room for you at the table but you don’t need to take a seat.”

— Maybe Burke (@believeinmaybe), in TikTok).

“Beyond the obvious demands – an end to sexual violence, an end to the wage gap – feminism must be class-conscious, and aware of the limiting culture of the gender binary. It needs to recognise that disabled people aren’t inherently defective, but rather that non-disabled people have failed at creating a physical world that serves all. Feminism must demand affordable, decent, secure housing, and a universal basic income. It should demand pay for full-time mothers and free childcare for working mothers. It should recognise that we live in a world in which women are constantly harangued into being lusted after, but punishes sex workers for using that situation to make a living. Feminism needs to thoroughly recognise that sexuality is fluid, and we need to dream of a world where people are not violently policed for transgressing rigid gender roles. Feminism needs to demand a world in which racist history is acknowledged and accounted for, in which reparations are distributed, in which race is completely deconstructed.”

— Reni Eddo-Lodge, Why I’m No Longer Talking to White People About Race (2017).

In Sojourner Truth’s 1883 obituary in the New York Times, the American abolitionist and suffragist was described as “a tall, masculine-looking figure – she was almost 6 feet high – and talked in a deep, guttural, powerful voice that made many people who heard her think that she was a man, and was imposing upon them by masquerading as a woman”.

[Will the narrative of the exhibition be a chronological one]

“Inevitably, an anti-racist education brings the past to the table. A past of abuse, cowardice, frustration and pride. A past of scientific racism, state-owned and legal. A past still present in the life of many. A present-past that (still) takes away future possibilities. To promote an anti-racist education is, above all, to identify the colonial heritage and social privileges – being anti-racist is a lot more than just recognising such heritage and privilege. It is to create alternatives, strategies and public politics of reparation. It is a lot more about listening and acting rather than speaking.”

— Danilo Cardoso, “Quem tem medo de uma educação antirracista?” [Whose Afraid of an Anti-Racist Education?]. Translated from the Portuguese, available here.

José Semedo Fernandes, a Portuguese lawyer of African descent, has told us that in school in the 1980s, the front row belonged to the white children, the second row was left empty and he occupied the back row. The class was always taught to the front row.

In Portugal, 80% of high school students from Portuguese-speaking African countries, or who are of African descent, take vocational courses. This is twice the number of children born in Portugal. These students do not benefit from the same educational preparation that might allow them to go on to higher education.

“It is not really a ‘Negro revolution’ that is upsetting the country. What is upsetting the country is a sense of its own identity. If, for example, one managed to change the curriculum in all the schools so that Negroes learned more about themselves and their real contributions to this culture, you would be liberating not only Negroes, you’d be liberating white people who know nothing about their own history. And the reason is that if you are compelled to lie about one aspect of anybody’s history, you must lie about it all. If you have to lie about my real role here, if you have to pretend that I hoed all that cotton just because I loved you, then you have done something to yourself. You are mad.”

— James Baldwin, A Talk to Teachers (1963). Read the complete text.

Gloria Jean Watkins, born in 1952, is better known by her nom de plume, bell hooks. According to the Chicago Manual of Style, the author, professor, feminist, and activist insists that her name is written in lower case and that this fact should be respected. “This makes life difficult, however, for those of us who cannot bear to begin a sentence with a lowercase letter,” to which the Chicago Manual of Style states: “We advise you to rewrite.”

Currently, in Portugal, when school textbooks refer to different professions, none of the people represented in the pictures are non-white.

When representing Portuguese colonialism and the slave trade, the prominent narrative in Portuguese schoolbooks is still that of black exclusion and inferiority.

“2. To imagine a time of silence

or few words

a time of chemistry and music

the hollows above your buttocks

traced by my hand

or, hair is like flesh, you said

an age of long silence

relief

from this tongue this slab of limestone

or reinforced concrete

fanatics and traders

dumped on this coast wildgreen clayred

that breathed once

in signals of smoke

sweep of the wind

knowledge of the oppressor

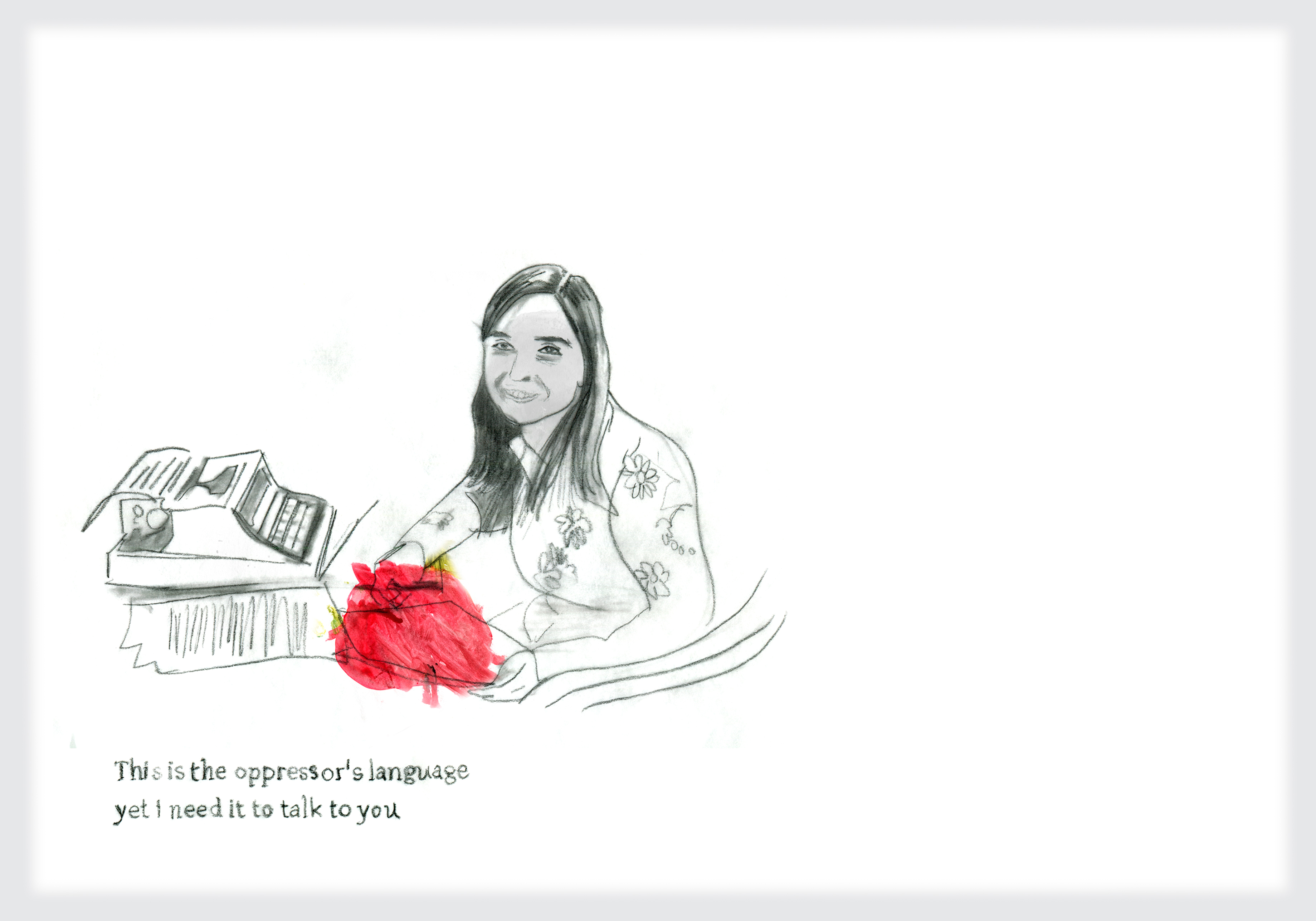

this is the oppressor's language

yet I need it to talk to you

…

5. I am composing on the typewriter late at night, thinking of today. How well we all spoke. A language is a map of our failures. Frederick Douglass wrote an English purer than Milton's. People suffer highly in poverty. There are methods but we do not use them. Joan, who could not read, spoke some peasant form of French. Some of the suffering are: it is hard to tell the truth; this is America; I cannot touch you now. In America we have only the present tense. I am in danger. You are in danger. The burning of a book arouses no sensation in me. I know it hurts to burn. There are flames of napalm in Catonsville, Maryland. I know it hurts to burn. The typewriter is overheated, my mouth is burning. I cannot touch you and this is the oppressor's language.”

— Adrienne Rich, “The Burning of Paper Instead of Children”. Read the complete text.

“When I realise how long it has taken for white Americans to acknowledge diverse languages of Native Americans, to accept that the speech their ancestral colonisers declared was merely grunts or gibberish was indeed language, it is difficult not to hear in standard English always the sound of slaughter and conquest. I think now of the grief of displaced ‘homeless’ Africans, forced to inhabit a world where they saw folks like themselves, inhabiting the same skin, the same condition, but who had no shared language to talk to one another, who needed ‘the oppressor’s language’. ‘This is the oppressor’s language yet I need it to talk to you.’ … I imagine, then, Africans first hearing English as ‘the oppressor’s language’ and then re-hearing it as a potential site of resistance (...) Possessing a shared language, black folks could find again a way to make community and a means to create the political solidarity necessary to resist … they nevertheless also reinvented, remade that language so that it would speak beyond the boundaries of conquest and domination (...) Enslaved black people took broken bits of English and made of them a counter-language.”

— bell hooks, Teaching to Transgress: Education as the Practice of Freedom (1994). Made available here.

When attending college, the artist Grada Kilomba was the only black student in the Clinical Psychology and Psychoanalysis Department at ISPA in Lisbon.

[Can I have a look at your notes]

“... language, as poetic as it can be, also has a political dimension that creates, pins down, and perpetuates relationships of power and violence, because every word we use defines the place of an identity.”

— Grada Kilomba, Memórias da Plantação: Episódios de Racismo Quotidiano (2019) [Plantation Memories: Episodes of Everyday Racism, 2008]. Translated from the Portuguese.

“Every word in our language contains, as if rolled in on itself, a ball of time made up of historical actions. While the prophet and the politician try to make words sacred by covering up their historicity, the profane task of restoring sacred words to daily usage falls to philosophy and poetry: undoing the knots of time, wresting words away from the conquerors in order to restore them to public space, where they can be the object of a collective re-signification.”

— Paul B. Preciado, An Apartment on Uranus (2020, English edition).

“I think that there isn’t anything more urgent than to start creating a new language. A vocabulary in which we can all find ourselves, in human condition.”

— Grada Kilomba, Memórias da Plantação: Episódios de Racismo Quotidiano (2019) [Plantation Memories: Episodes of Everyday Racism, 2008]. Translated from the Portuguese.

“I’m convinced that struggling with feelings of shame, and the possibility of humiliation, is psychologically, politically, artistically meaningful. This is part of the necessary work of whiteness, or recovery from whiteness, which is an okay phrase as long as everyone accepts that the recovery is never really over and the repair is never complete; that’s another part of the beautiful struggle. I’m convinced that part of resisting normative whiteness is resisting the urge to have a breakdown, or meltdown, confess my sins, and seek absolution—that is, to make my feelings a catastrophe that has to be dealt with.”

— Jess Row, White Flights: Race, Fiction and the American Imagination (2019).

“The global movement for the decolonisation of knowledge and imagination has risen from within academia, activism, social movements and artistic communities. This multifaceted and transdisciplinary movement now defends that after decades of independence, political and institutional decolonisation should now be followed by the decolonisation of knowledge and culture to ensure the effective reversal of colonisation by western societies.”

— Joacine Katar Moreira, in a speech about her proposal for a programme to decolonise culture. Translated from the Portuguese.

“Let the museums remain empty and the pedestals bare. Let nothing be installed upon them. It is necessary to leave room for utopia regardless of whether it ever arrives. It is necessary to make room for living bodies. Less metal and more voice, less stone and more flesh (…) We do not need any more statues. Let’s not ask for marble or metal to fill those pedestals. Let’s climb up on them and tell our own stories of survival and liberation.”

— Paul B. Preciado, “When Statues Fall”, Artforum (2020). Read the complete text.

[How much longer?]

At a certain point in her life, Judith Sylvia Cohen decided she wanted an independent name that wasn’t connected to a man by heritage or marriage. She adopted the nickname the gallerist Rolf Nelson gave her because of her thick accent. Judy Chicago was born.

“As Jude Kelly, artistic director of London’s Southbank Centre for Performing Arts, has said, being inclusive is not about ‘standing in the middle and saying, “I’d like to include you” – you have to stand in a different place.’”

— Lucy R. Lippard, foreword in Maura Reilly, Curatorial Activism. Towards an Ethics of Curating (2018).

The first memorial ever erected in Portugal to celebrate the abolition of slavery and pay homage to its victims was made possible in 2018 through the Participatory Budgeting (PB), a programme run by the Lisbon Municipality.

“Instead of making excuses, denying statistics, or shying away from inequalities of gender, race, and sexuality, we must face these issues head-on in order to come up with strategies and solutions that will guarantee equal opportunity and exposure. With a little more energy and action, the creation of a just art world does not have to be a pipe dream.”

— Maura Reilly, Curatorial Activism. Towards an Ethics of Curating (2018).

[Can you jot that down?]

“The future of our earth may depend upon the ability of all women to identify and develop new definitions of power and new patterns of relating across difference.”

— Roxane Gay, introduction in The Selected Works of Audre Lorde (2020). Read the complete text.

|

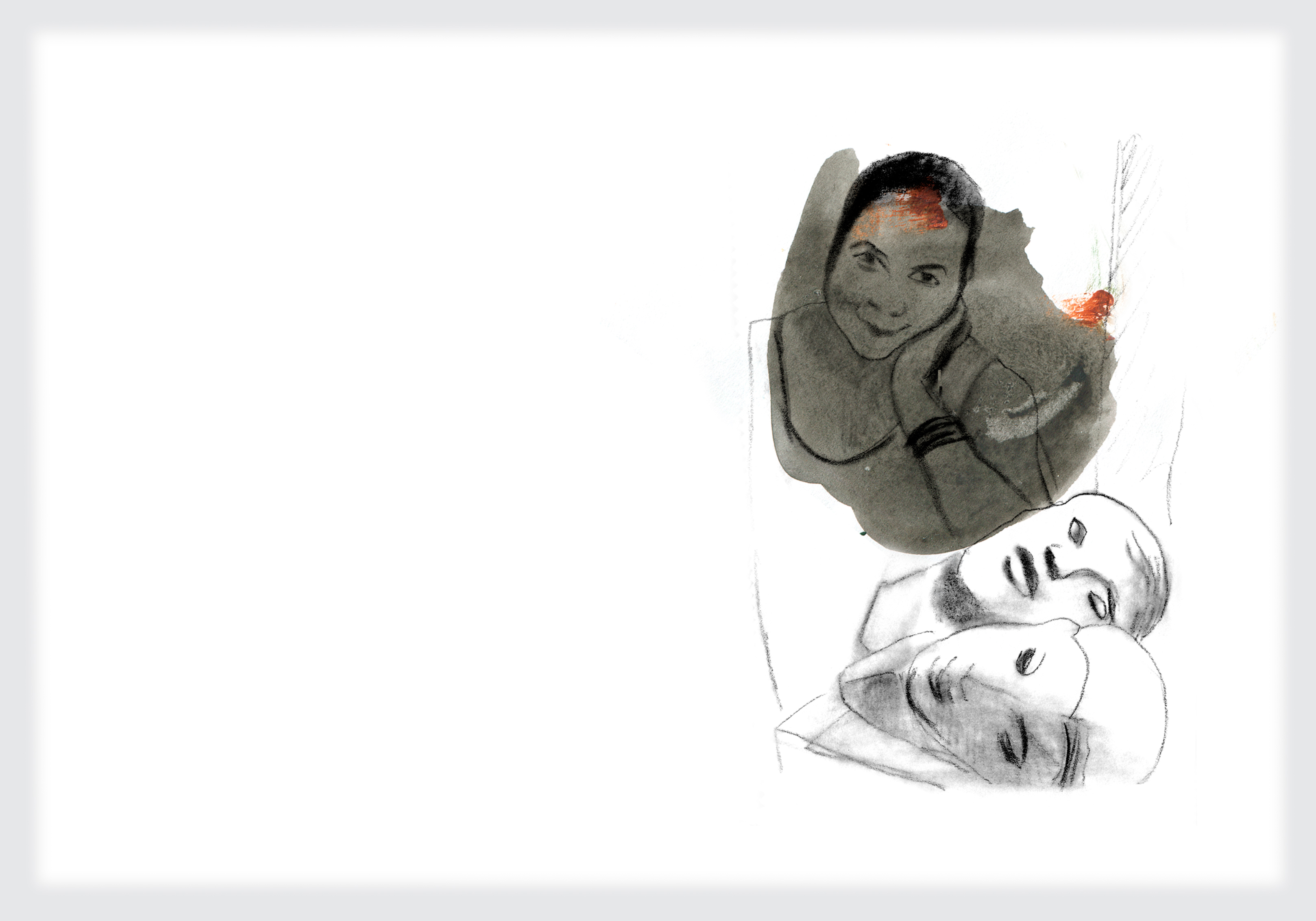

Drawings by Susana Gaudêncio: Tony Morrison, quote by Sojouner Truth, Audre Lorde. bell hooks, Adrianne Richie, Maybe Burke, Joacine Katar Moreira, quote by Paul B. Preciado, and drawing based on a project by Kiluanji Kia Henda. |

|

|

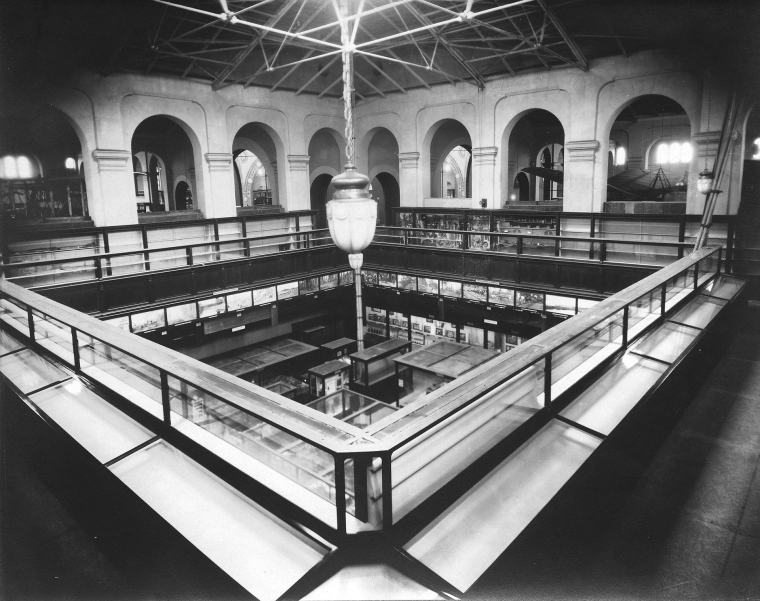

(Cover image) Empty exhibit case at the United States National Museum, now known as the Arts and Industries Building, 1880s, USA. © Smithsonian Institution Archives. Image # SIA-75-11093-16A. |

|

Empty Exhibit Cases gathers three cisgender white women working in the arts, Susana Pomba, Susana Gaudêncio and Maribel Mendes Sobreira, on their way to become life-long anti-racist and effective allies, as artists, teachers, researchers, curators, historians, writers, or authors. The project delivers a group of essays (in diary mode), that might be hybrid in form, and attempt to dissect various questions and struggles, all in the context of the daily personal and professional lives of the three participants. They will also engage in conversation with activist groups, scholars, or cultural agents. |

Based on diary-keeping as a form of writing, the Mode Diaries initiative creates a field of interpretative potentialities within the context of maat Mode 2020, a public, experimental and participatory exhibition and activity programme under the motto “Prototyping the museum”. This is the scope that justifies and enables the twisting of the meaning commonly attributed to the term “diary” by transforming what’s individualised into collective, private into public, singular into plural, etc. |