After the Dust Settles: Comprised Particles a digital performance by Ibiye Camp.

Shown here at maat ext. Cinema from 17 May to 6 September 2021.

Through visual storytelling, Ibiye Camp converts images she received on WhatsApp from her family in Nigeria. Living away from West Africa and unable to visit due to Covid-19, the internet is one of the most visible aspects of globalisation. Using Gaming Engine Software Ibiye transforms the images she received into 3D traces of space. In a digital performance, Ibiye takes us through a constructed digital space, confronting the effects of oil extraction in the Niger Delta. Using game physics, partial systems, and point cloud datasets, Ibiye speculates the future of the Niger Delta.

Originally shown at OPEN/CLOSED SYSTEMS, the 2021 Spring Opening event at maat, on 23 April 2021, in relation to After the Dust Settles (2020), a multimedia installation by Ibiye Camp included in the exhibition X is Not a Small Country (18/03–06/09/2021).

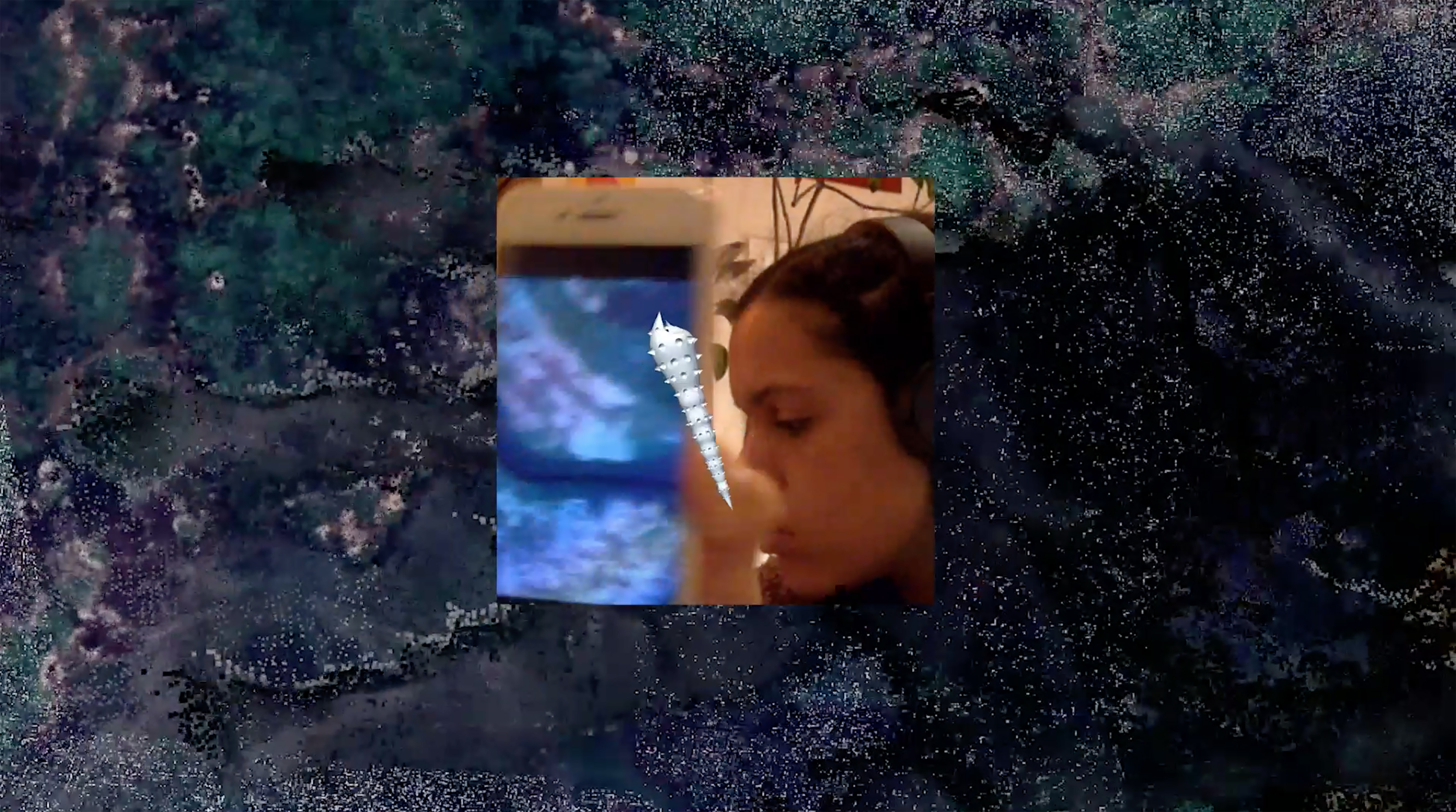

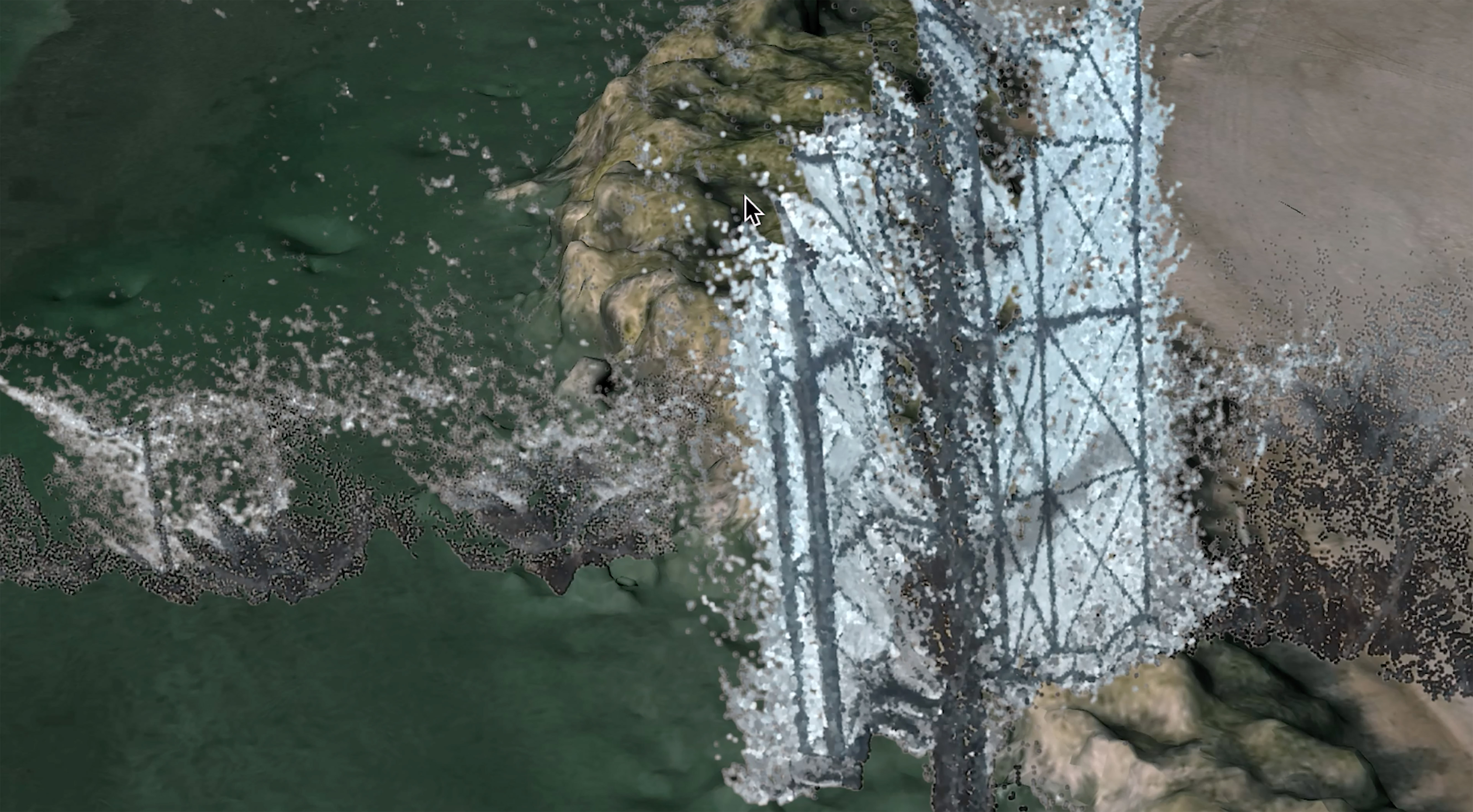

Image: video still from “After the Dust Settles: Comprised Particles” (2021) by Ibiye Camp. Courtesy of the artist.

After the Dust Settles

by Ibiye Camp

Communities in the Niger Delta region of Nigeria are confronted with an environmental catastrophe that began in the 1950s with the arrival of multinational petroleum corporations. Under the pressures of globalisation, a space once rich in biodiversity has been devastated by unsustainable practices in oil and gas extraction, causing spills and pollution on a vast scale. This has shifted how the landscape is governed, and new formations of farming and care among its citizens have emerged.

Divided into 3 frames, After the Dust Settles (2020) takes visitors on a journey from Google Earth aerial imagery to augmented reality to speculate on the region’s future. The plummeting demand caused by the current pandemic has highlighted the oil market’s volatility, and growing climate action lends hope for a post-petroleum future. But the human and environmental effects on the delta will continue to reverberate.

Ibiye Camp, “After the Dust Settles” (2020), research image. Courtesy of the artist.

Video still from “After the Dust Settles: Comprised Particles” (2021) by Ibiye Camp. Courtesy of the artist.

Ibiye Camp

-

"After the Dust Settles", 2020

Multimedia installation; dimensions variable -

"Buguma, Rivers State, Nigeria", 2020

Tablet, augmented reality, steel frame and banner; 337 × 174 × 310 cm -

"Port Harcourt and Ogoniland, Rivers State, Nigeria", 2020

Tablet, augmented reality, steel frame and banners; 374 × 186 × 124 cm -

"Warri, Delta State, and Buguma, Rivers State, Nigeria", 2020

Tablet, augmented reality, steel frame and banners; 372 × 372 × 429 cm

Courtesy of the artist.

View of the exhibition X is Not a Small Country – Unravelling the Post-Global Era with “After the Dust Settles” (2020) by Ibiye Camp. Photography: Francisco Nogueira. Courtesy of BUREAU and EDP Foundation / maat.

Ibiye Camp, “After the Dust Settles” (2020), research image. Courtesy of the artist.

Interview with Ibiye Camp

by Aric Chen and Martina Muzi

Aric Chen / Martina Muzi

Can you describe your personal connection to the Niger Delta, and any first-hand observations or experiences you have on its environmental devastation?

Ibiye Camp

I’m British Nigerian. My mother’s family lives in Buguma, which is in Rivers State in Nigeria. I spent my childhood travelling to Port Harcourt and Buguma. In the ‘90s, we would travel by speedboat to reach Buguma City. It may be a romanticised memory, but I recall the journey as a vibrant green experience with a scent of petrol in the air, most likely from the speedboat motor. I travelled back to Buguma for the first time in 13 years at the beginning of 2020. Instead of a speedboat, we drove over newly constructed concrete bridges, which link the islands of the Kalabari Kingdom together. The environmental devastation was evident during the journey; the landscape wasn’t as green and the views were obscured by the smog in the air. The soot became more present and shocking once we arrived home. After unpacking and greeting family, we found that the soles of our feet had turned black just walking from one side of the room to the other. Using a traditional broom made from palm fronds, we swept away the soot that had built up in the house, and in the curtains and furniture. The environmental devastation is a subtle but monumental part of everyday life.

Aric Chen / Martina Muzi

You’ve referred to how the power of the oil companies has undermined the area’s sovereignty – for example, through the laying of unprotected pipelines without regard to the property of local citizens – while also producing “new formations of farming and care.” What are these new formations?

Ibiye Camp

The new formations of care I’ve concentrated on are formed by the Kalabari periwinkle pickers, the fishery industry and market traders. The coastal communities are the ones most affected by oil vandalism. So, there’s been a huge amount of unemployment, especially in the younger generations. Traditionally, Kalabari women were known as periwinkle pickers and traders in Rivers State. However, today most tribes in the neighbouring area, such as the Ogonis, Andoni, Ikwerre and Igbo, have begun picking periwinkles in the mangrove forests. The pickers are mainly women and are described as the mothers of the village. They work profusely when the tide is low. In a canoe, they transport the seafood collected and roast it on land; this is then traded in local and neighbouring markets. When walking through the compounds of Buguma City in 2020, I could see heaps of periwinkle shells belonging to one family. These shells would provide various other revenues when sold to builders, road constructors and other projects as materials.

The environmental devastation is a subtle but monumental part of everyday life.

Ibiye Camp

Video still from “After the Dust Settles: Comprised Particles” (2021) by Ibiye Camp. Courtesy of the artist.

Ibiye Camp, “After the Dust Settles”, 2020, research image. Courtesy of the artist.

View of the exhibition X is Not a Small Country – Unravelling the Post-Global Era with “After the Dust Settles” (2020) by Ibiye Camp. Photography: Pedro Pina. Courtesy of EDP Foundation / maat.

Video still from “After the Dust Settles: Comprised Particles” (2021) by Ibiye Camp. Courtesy of the artist.

Aric Chen / Martina Muzi

Had it not been for the pandemic, you would have travelled to the Niger Delta for your research on this project. Instead, you relied on online tools. How has working remotely impacted this project and your thoughts on your practice and methodologies, and the role of technology in them?

Ibiye Camp

On my last visit to Buguma, I attended a masquerade performance. It was a much more technical production than it was in the ‘90s. It used to be rare to even have an analogue camera at a masquerade event, but in early 2020 there were multiple camera crews with equipment ranging from SLR cameras to iPads and drones, all recording the performance and audience. I see the augmented reality screens in After the Dust Settles as representations of how Buguma has become extensively televised and accessible online. There are now Kalabari Kingdom accounts on Twitter and YouTube. This is how I keep up to date with the events there. The internet is the only thing keeping globalisation alive.

Aric Chen / Martina Muzi

Can you explain how you got your datasets in tracking the movement of the periwinkle pickers?

Ibiye Camp

As I’ve been working on this project from afar, from London,in order to make the 3D models, I worked with data collected from video footage taken in the mangrove forests. This includes my own mobile phone videos from 2020 and YouTube footage, particularly from the Kalabari TV channel. What is interesting about point clouds is that the points represent a 3D shape, but there is also an absence as they only show the external surfaces of these shapes. Many point cloud studies provide just a vague indication or indefinite trace. This allows the identities of the space to remain anonymous it is not as accurate as tracking the movements of individuals.

The internet is the only thing keeping globalisation alive.

Ibiye Camp

Aric Chen / Martina Muzi

For you, what is the value of speculation in addressing current issues? Working remotely means that the project becomes more of a speculation, a collection of narratives – rather than a data study of actual conditions.

Ibiye Camp

I’ve used a game engine to speculate on the human and environmental effects on the delta, post-oil extraction. Speculating using augmented reality allows you to dive into other indeterminate realities to explore other dimensions in the conversation about afro-futurism. Here, I use afro-futurism to consider other universes of alternatives, and alternative meanings; when you look through the android screen, you see this alternative information on the installation’s maps of the Niger Delta.

Ibiye Camp

-

"After the Dust Settles", 2020

Multimedia installation; dimensions variable -

"Buguma, Rivers State, Nigeria", 2020

Tablet, augmented reality, steel frame and banner; 337 × 174 × 310 cm -

"Port Harcourt and Ogoniland, Rivers State, Nigeria", 2020

Tablet, augmented reality, steel frame and banners; 374 × 186 × 124 cm -

"Warri, Delta State, and Buguma, Rivers State, Nigeria", 2020

Tablet, augmented reality, steel frame and banners; 372 × 372 × 429 cm

Courtesy of the artist.

View of the exhibition X is Not a Small Country – Unravelling the Post-Global Era with “After the Dust Settles”, 2020, by Ibiye Camp. Photography: Francisco Nogueira. Courtesy of BUREAU and EDP Foundation / maat.

Aric Chen / Martina Muzi

What do you think is the main lesson from the speculation you present in After the Dust Settles? Here, the global has unravelled in a way that presumably benefits the local population – and yet they are still dealing with the aftermath. Could the global also play a role in healing?

Ibiye Camp

The global can play a role in healing the damage to the environment and the livelihoods of the communities in Rivers State. For example, the Kalabari TV YouTube channel documents information from various parts of the Kalabari Ethnic Nationality. Moments of celebration, political events and even investigations have become globally accessible. After the Dust Settles was informed by a YouTube video titled “ISAM”. The intention of this report was to give a platform to the Periwinkle Mothers, farmers and market traders. The internet has become a space where Niger Delta environmentalists, reporters and activists can communicate and distribute knowledge beyond Rivers State.

Based in London, Ibiye Camp (b. 1991, United Kingdom) is a multidisciplinary artist and tutor at the Royal College of Art. Her work engages with technology, trade and material within the African diaspora, while utilising architectural tools to create 3D models, sound and video, accompanied by augmented reality, in order to highlight the inherent biases and conflicts in technology.

Curated by Aric Chen, with Martina Muzi, X is Not a Small Country – Unravelling the Post-Global Era includes nine newly created projects by international practitioners working across the fields of design, architecture and art who investigate, articulate and critique the current convoluted state of the world from multiple geographic perspectives.

In collaboration with maat, Art Jameel presents a series of moving image and video works, curated by Róisín Tapponi, in response to “Tactile Cinema” (2021), the site-specific installation by Bricklab, which offers a multi-screening space for filmmakers and visual artists from the Arab region.

The exhibition is accompanied by an editorial collaboration with e-flux Architecture entitled Cascades presenting original fictional writings that expand on the show’s themes while questioning what it means to speculate at a time increasingly defined not by linear narratives, but rather transactional opportunism, black swan events and unintended consequences.