Jamaika

a 2020 video documentary by José Sarmento Matos.

Shown here at maat ext. Cinema from 3 May to 6 September 2021.

Photography, videography, documentary: José Sarmento Matos

Music: Kid Robinn, original theme “Perspectiva”

Editing and field assistance: Gersiley Sousa, Neide Jordão

Video editing: Filipe Tavares, José Sarmento Matos

Videos and interviews: Alda Pontes, Arioste Mandinga, Aurora Coxi, Asmir Djonis Bull, Diego Coxi, Edna Nazaré, Ivone Maxima, José Sarmento Matos, Leopoldo Pereira, Lurdes Pontes, Manuela Pedro, Neide Jordão, Roberto Cravid, Salimo Mendes, Telma Reis

Translation: Constança Trewinnard

Supported by the National Geographic Society

Image: video still from "Jamaika" (2020) by José Sarmento Matos.

Presented at maat in the context of the exhibition X is Not a Small Country (18/03–06/09/2021) as part of Model of Jamaika (2021), a collaborative work by Paulo Moreira, with Chão – Oficina de Etnografia Urbana and José Sarmento Matos.

Model of Jamaika

by Paulo Moreira, with Chão – Oficina de Etnografia Urbana and José Sarmento Matos

Beginning in the mid-1980s, large numbers of people from Portugal’s newly independent African colonies migrated to Bairro de Vale de Chícharos, more commonly known as "Bairro da Jamaika", on the outskirts of Lisbon. Seeking safety and economic stability, these arrivals – from Angola, Guinea-Bissau, São Tomé and Príncipe and other African nations, alongside a small population of Roma – appropriated and inhabited the area to create a thriving, albeit unauthorised, community.

Model of Jamaika presents a 1:10 scale, walk-in model of the neighbourhood’s recently demolished Bloco 10. The installation narrates some of the residents’ ongoing disputes with private landowners and local authorities, while presenting aspects of their everyday lives and still-unfolding future.

Model of Jamaika (2021), a collaborative work by Paulo Moreira, with Chão – Oficina de Etnografia Urbana and José Sarmento Matos is presented at maat in the context of the exhibition X is Not a Small Country (18/03–06/09/2021), curated by Aric Chen, with Martina Muzi.

-

View of the exhibition X is Not a Small Country – Unravelling the Post-Global Era with “Model of Jamaika” and, on the left, “Teeter-Totter Wall” (2019–2021) by Rael San Fratello. Photography: Bruno Lopes. Courtesy of the authors and EDP Foundation / maat.

"Model of Jamaika", 2021

Model scale 1:10, plastered MDF, metallic structure, photographs, objects, video and text. 250 × 190 × 400 cm

Courtesy of the authors.

Concept: Paulo Moreira, Chão – Oficina de Etnografia Urbana, José Sarmento Matos

Coordination: Paulo Moreira

Project: Paulo Moreira Architectures (Paulo Moreira, Hermínio Santos, Joana Graça, Mario Martínez)

Model: Arte Leite

Structure: Panoramah

Chronology: Chão

Text: Residents'Assembly of the 6 de Maio Neighbourhood (Amadora),Torre Neighbourhood (Loures), Jamaica Neighbourhood (Seixal), Quinta da Fonte (Loures), with support from Habita, Gestual, Chão, Camarate Parish, Secretariado Diocesano de Lisboa da Pastoral dos Ciganos

Manuscript: Maria Cesaltina das Neves

Graphic design: Pê

Photography: José Sarmento Matos

In memory of Salimo Mendes.

Interview with Paulo Moreira

by Aric Chen and Martina Muzi

Aric Chen / Martina Muzi

You were in some ways a natural participant for this show, given your 2011 project Angola is not a small country. Could you tell us about that project?

Paulo Moreira

Angola is not a small country is a play on a colonial propaganda map entitled “Portugal is not a small country” [also the initial prompt for X is Not a Small Country], created by Henrique Galvão in 1934. The original map showed a cartographic illusion aimed at emphasising the supposed grandeur of the “empire” in comparison to the small area occupied by mainland Portugal. But the colonial paradigm changed. Angola became an independent country and an economic superpower fuelled by the oil industry. It has attracted thousands of Portuguese people in search of wealth and prosperity, and it also began to have an influence on many sectors of the economy here. The map was a provocative depiction of the relationship between Portugal and Angola at that particular time.

Aric Chen / Martina Muzi

In the context of the Jamaica Neighbourhood, how would you describe the relationship between decolonisation, coloniser and formerly colonised?

Paulo Moreira

In a way, "Jamaica" is a concrete manifestation of the map’s general concept. Following the independence of the former Portuguese colonies, large numbers of people moved to Portugal in search of a safe haven. Around the same time, the contractor who was building on the land now occupied by Jamaica went bankrupt and fled to Brazil. Gradually, migrant families began to move into the abandoned, unfinished structures. Later, Seixal municipal council sold the property at a public auction to a company called Urbangol – a very “Angola-esque” name. The company later came into conflict with the council because the agreement stipulated that the site would be cleared of all inhabitants. But that obviously didn’t happen.

Detail of “Model of Jamaika” with the photographs by José Sarmento Matos. Photography: Pedro Pina. Courtesy of the authors and EDP Foundation / maat.

|

|

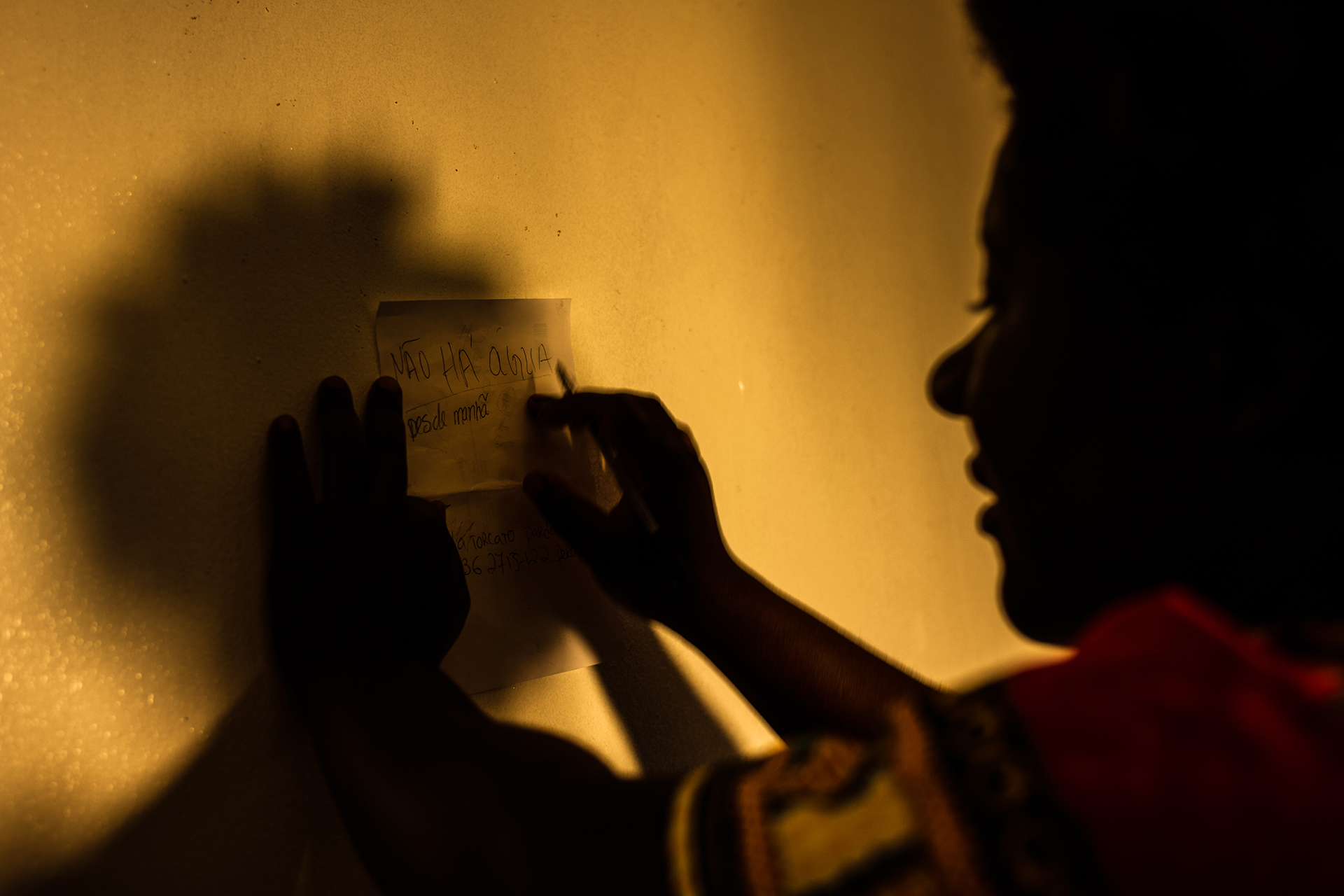

José Sarmento Matos, from the series “Jamaika” (2021). Courtesy of the artist.

Aric Chen / Martina Muzi

During your research for Model of Jamaika, how did you see your role as an architect?

Paulo Moreira

My research points to an expansion of the role of architects as facilitators of local knowledge. My initial approach involved finding and making contact with local residents, and I was lucky to meet Mr. Salimo Mendes, the charismatic president of the residents’ committee, the Associação de Desenvolvimento Social de Vale de Chícharos. Mr Mendes welcomed me to his neighbourhood and his vision enabled links with a group called Chão – Oficina de Etnografia Urbana, as well as José Sarmento Matos, an emerging photojournalist who is producing a thorough documentary project on the area. With all these people on board, we initiated an incredibly fruitful process. But we had to overcome some very delicate situations. Sadly, we lost Mr Mendes in December. He was the true facilitator of the project, which would never have come into being without his support. If nothing else, I hope the project serves as a greatly deserved tribute to everything he did for the community in the Jamaica Neighbourhood.

Aric Chen / Martina Muzi

What were some of the most surprising findings or observations for you as you researched "Jamaica" and spent time with its residents, and how do you see their future?

Paulo Moreira

Looking beyond the immediate issue of the hazardous housing conditions, my observations hint at other reasons for the urgent calls to dismantle the neighbourhood. "Jamaica" has become a focus for rage against black and migrant communities in Portugal, which is exacerbated by some far-right movements. A photo of Jamaica was recently shown at a presidential debate on TV by a politician, who labelled the residents “thugs”. I believe that demolishing Jamaica and other deprived neighbourhoods might actually weaken and undermine these brutal narratives. So, the best outcome I can envisage for "Jamaica" is its demise, but in the meantime, it’s important to keep records and consolidate collective memories.

Aric Chen / Martina Muzi

That’s an interesting take. "Jamaica", as you say, has been entangled in disputes. It’s a bone of contention and a microcosm for how broader social, political, economic and racial frictions play out. How can a museum represent a valuable space of debate for addressing these issues?

Paulo Moreira

I believe that museums should cause some discomfort. I see the installation [comprising a physical model of a now-demolished Jamaica building] as a kind of Trojan horse, and not just because of the well-known disputes between "Jamaica" and EDP [the electricity company]. The model is an “anchor” generating further conversation around the neighbourhood. Firstly, it’s designed as a walk-in structure to display Chão and José’s work, bringing to the fore many voices that largely go unheard in Portuguese society, never mind in cultural spaces per se. Secondly, we intend to supplement the installation with a public programme addressing racism, marginalised art and the question of policies on resettlement processes. By doing this, we celebrate and acknowledge the neighbourhood as part of the city while bringing in key constituents: activists with something to say about the case, and decision-makers who are more likely to agree to speak out on this controversial topic when asked by a reputable museum than if approached from within the neighbourhood.

I believe that museums should cause some discomfort.

Paulo Moreira

Detail of “Model of Jamaika” with the photographs by José Sarmento Matos. Photography: Pedro Pina. Courtesy of the authors and EDP Foundation / maat.

José Sarmento Matos, from the series “Jamaika” (2021). Courtesy of the artist.

|

|

Aric Chen / Martina Muzi

Speaking of the model, there’s a double-entendre in the title Model of Jamaika that you gave your installation. You also spell it with a “K,” instead of a “C,” like the residents do. In what ways do the micro-histories of "Jamaica" represent a model that might translate into a wider, even global, scale? How has it influenced your own socially oriented practice?

Paulo Moreira

Jamaica is subject to multiple forms of injustice. It’s fair to say that this invitation to develop a project at maat gives us a public prominence that we can use to help blur boundaries between this elite cultural institution and marginalised areas of the city. The piece itself conveys this idea. The model reflects the textures and imperfections of the self-built neighbourhood. Craftsman Arte Leite did a brilliant job. At the same time, the structure supporting the model was made by a metalworking company, Panoramah, which built maat itself. This tells you all you need to know. So Model of Jamaika shows that it is possible to reconcile what might have seemed irreconcilable. This conclusion can be extrapolated to a larger scale. I’m interested in drawing connections between these difficult cases and their wider urban contexts. I believe that in doing so, I’m helping to build bridges instead of walls. That must be one of the main contributions I can make as an architect and citizen.

Paulo Moreira (b. 1980, Portugal) is the founder of Paulo Moreira Architectures, a Porto-based studio that develops architectural, cultural and research projects for “post-boom times”. Currently he is a post-doctoral fellow in the Africa Habitat research project, coordinated by FAUL and funded by FCT and AKDN. In “Model of Jamaika”, he worked with Chão – Oficina de Etnografia Urbana, a collective working in the Jamaica Neighbourhood since 2015, and José Sarmento Matos, a photojournalist developing a documentary project supported by the National Geographic Covid-19 emergency fund.

Curated by Aric Chen, with Martina Muzi, X is Not a Small Country – Unravelling the Post-Global Era includes nine newly created projects by international practitioners working across the fields of design, architecture and art who investigate, articulate and critique the current convoluted state of the world from multiple geographic perspectives.

In collaboration with maat, Art Jameel presents a series of moving image and video works, curated by Róisín Tapponi, in response to “Tactile Cinema” (2021), a site-specific installation by Bricklab, which offers a multi-screening space for filmmakers and visual artists from the Arab region.

The exhibition is accompanied by an editorial collaboration with e-flux Architecture entitled Cascades presenting presenting original fictional writings that expand on the show’s themes while questioning what it means to speculate at a time increasingly defined not by linear narratives, but rather transactional opportunism, black swan events and unintended consequences.