While the movement of goods between India and China is usually discussed in terms of trade, these imported and exported objects have lives that far exceed their financial value. They enter into dialogical relationships with people and their desires, values and practices to create new interactions, concepts and spaces – a politics that complicates conventional understandings of geopolitical exchanges.

Itinerant Desires: Itineraries of Usual and Unusual Commodities (2020), by BARD Studio, looks at the lives of some “usual and unusual commodities” as they travel from China to India to inhabit a transactional object/space, represented here by a scaffold. This scaffold draws its form from the urbanity of Mumbai, where high densities and intensities of built form create new vectors for activities, networks and livelihoods, while providing a space for intimacies and rest in the museum.

|

View of the exhibition X is Not a Small Country – Unravelling the Post-Global Era with “Itinerant Desires: Itineraries of Usual and Unusual Commodities” (2020) by BARD Studio. Photography: Bruno Lopes. Courtesy of BARD Studio and EDP Foundation / maat. |

Bard Studio Steel frame structure with readymade objects, plastic, cloth, wood, A5 size digitally printed books in paper, webcams and monitors 800 × 850 × 420 cm |

3D render for “Itinerant Desires: Itineraries of Usual and Unusual Commodities” (2020) by BARD Studio.

INTERVIEW WITH RUPALI GUPTE + PRASAD SHETTY (BARD STUDIO)

by Aric Chen and Martina Muzi

Aric Chen / Martina Muzi

What types of objects have you included in the installation and how did you decide on them?

BARD Studio

Imports from China are not only the specialised technological devices that are not produced in India, but also a variety of everyday objects that have in fact been historically produced here [in India]. Along with these, there are other “strange” objects that people had only imagined, but that were never produced here as they were probably found unfeasible in terms of a demand-supply logic. So, while we have televisions, mobile phones, shoes and furniture, we also have back scratchers, ear diggers, invisible ink pens, spy cameras, idols of gods, large plastic plants, etc.

Aric Chen / Martina Muzi

In this project, you refer to “usual and unusual commodities.” How would you define, and distinguish between, the “usual” and the “unusual” – or are these fluid designations?

BARD Studio

While a lot of utilitarian devices and objects like electronic goods, shoes, appliances, etc. come to India from China, there are also these ear scratchers, invisible ink pens, various types of massagers, that arrive. Our idea of the unusual relates not only to the unfamiliarity associated with some of these objects [in India], but also to ways in which these objects unassumingly respond to some very instinctual desires. Also, objects like these, so far, have never been in the realm of mass production in India. They were produced largely through cottage industries.

Aric Chen / Martina Muzi

What is the significance of “desire” here?

BARD Studio

Take the case of the invisible ink pen. It is made in some factory in China, sold in the Mumbai local trains for 10 rupees (20 cents), and people actually go ahead and buy it. These are not children who buy such bizarre objects, but rather fully-fledged adults. Why do they buy these objects? Obviously, the objects are not of any particular use, and probably get added to the number of objects that lie around in their homes, gathering dust, to be thrown away one day. People buy these for that moment, when they let themselves float in imaginary worlds, where they may be spies, sending secret messages. This absurd, but very instinctual, desire creates the demand here. And to think that there is someone in China who is actually designing for this madness – perhaps not thinking of the desire of the user, but on a trip to innovate, testing the possibility of creating such a pen. The objects transcend transactional logics here.

View of the exhibition X is Not a Small Country – Unravelling the Post-Global Era with “Itinerant Desires: Itineraries of Usual and Unusual Commodities” (2020) by BARD Studio. Photography: Bruno Lopes. Courtesy of the authors and EDP Foundation / maat.

Bard Studio

"Itinerant Desires: Itineraries of Usual and Unusual Commodities", 2020

Steel frame structure with readymade objects, plastic, cloth, wood, A5 size digitally printed books in paper, webcams and monitors

800 × 850 × 420 cm

Courtesy of the artists

Aric Chen / Martina Muzi

As you were working on this project, the longstanding conflict between the Chinese and Indian governments over their disputed border in the Himalayas flared up into a series of deadly skirmishes. In the ensuing diplomatic row, the Indian government banned the use of Chinese apps within its borders. How has this sudden cut-off in trade and exchange, and the potential for more to come, affected your thinking, or how might one speculate about its impact on the embedded narratives in your objects?

BARD Studio

The aggressions in the Himalayas are not new and are typical of exchanges in border areas. We think that the sudden highlighting of this aggression and such bans are superficial attempts to hide some other powerful narratives and are quite temporary. Things will mutate and emerge in different ways. However, there was some nationalistic euphoria created due to this highlighted crisis, and people demonstrated by throwing away Chinese televisions, etc. But soon they realised that their new TV was produced in Vietnam by a factory owned by a Chinese entrepreneur. The ties are far too material and deep to be destroyed by the abstractions of nationalism, etc.

Aric Chen / Martina Muzi

Currently, the Chinese government is promoting an economic policy of “dual circulation” by which, on the one hand, technology and capital are developed and sustained internally in the name of self-sufficiency, while trade and other flows remain open to the outside world. Could we consider your Itinerant Objects as representing a kind of dual circulation and, if so, in what ways?

BARD Studio

The "itinerant objects" have their own dual circulation: the trade circulation through factories, shipments, warehouses, shops and houses; and the lived-life circulations through innovations, journeys, desires, meanings, etc.

Aric Chen / Martina Muzi

In your installation, you offer narratives, in the form of books, that describe the ways in which some of these objects acquire new uses and meanings as they circulate. Could you give some examples?

BARD Studio

The objects become part of the everyday lives of people – they mean many things – from being utilitarian commodities (like shoes, appliances, etc.) to enigmatic and sacred symbols (like statues of gods and other ritualistic objects), to objects of desire and pleasure (like the invisible ink pens, the spy cameras, etc.) and objects that create experience and identity (like LED lights, plastic flowers, and other decorative things). The narratives are termed “itinerant desires” and are stories of people’s everyday relationships implicated in this trade and its afterlife. They also take us to various geographies and spaces that get entangled in the narratives of transaction.

Our idea of the unusual relates not only to the unfamiliarity associated with some of these objects [in India], but also to ways in which these objects unassumingly respond to some very instinctual desires.

BARD Studio |

BARD Studio, “Itinerant Desires: Computer Peripherals” (pages 10-12), 2020.

BARD Studio, “Itinerant Desires: Sound Devices and Televisions” (pages 12-15), 2020.

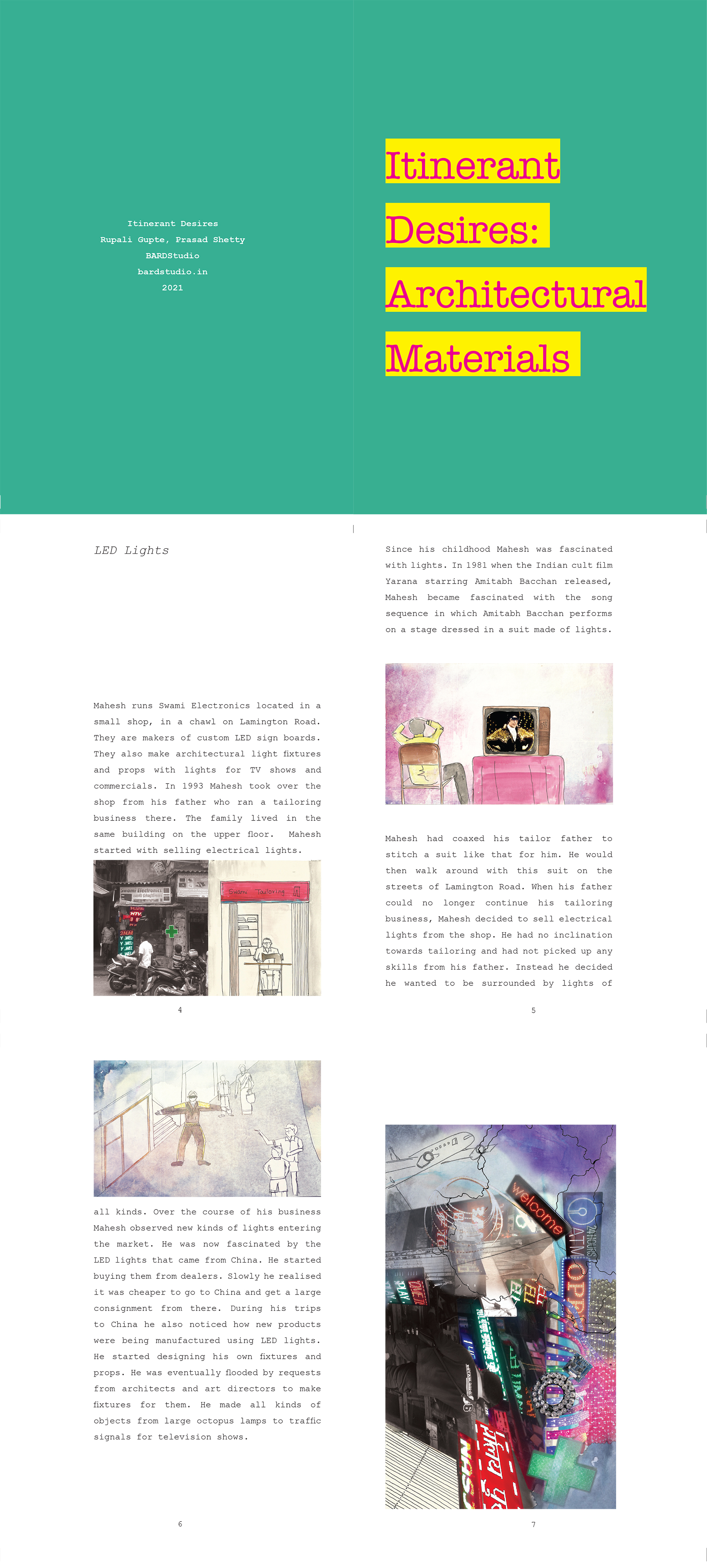

BARD Studio, “Itinerant Desires: Architectural Materials” (pages 4-7), 2020.

BARD Studio, “Itinerant Desires: Invisible Ink Pens” (pages 4-5), 2020.

BARD Studio, “Itinerant Desires: Cameras” (pages 12-13), 2020.

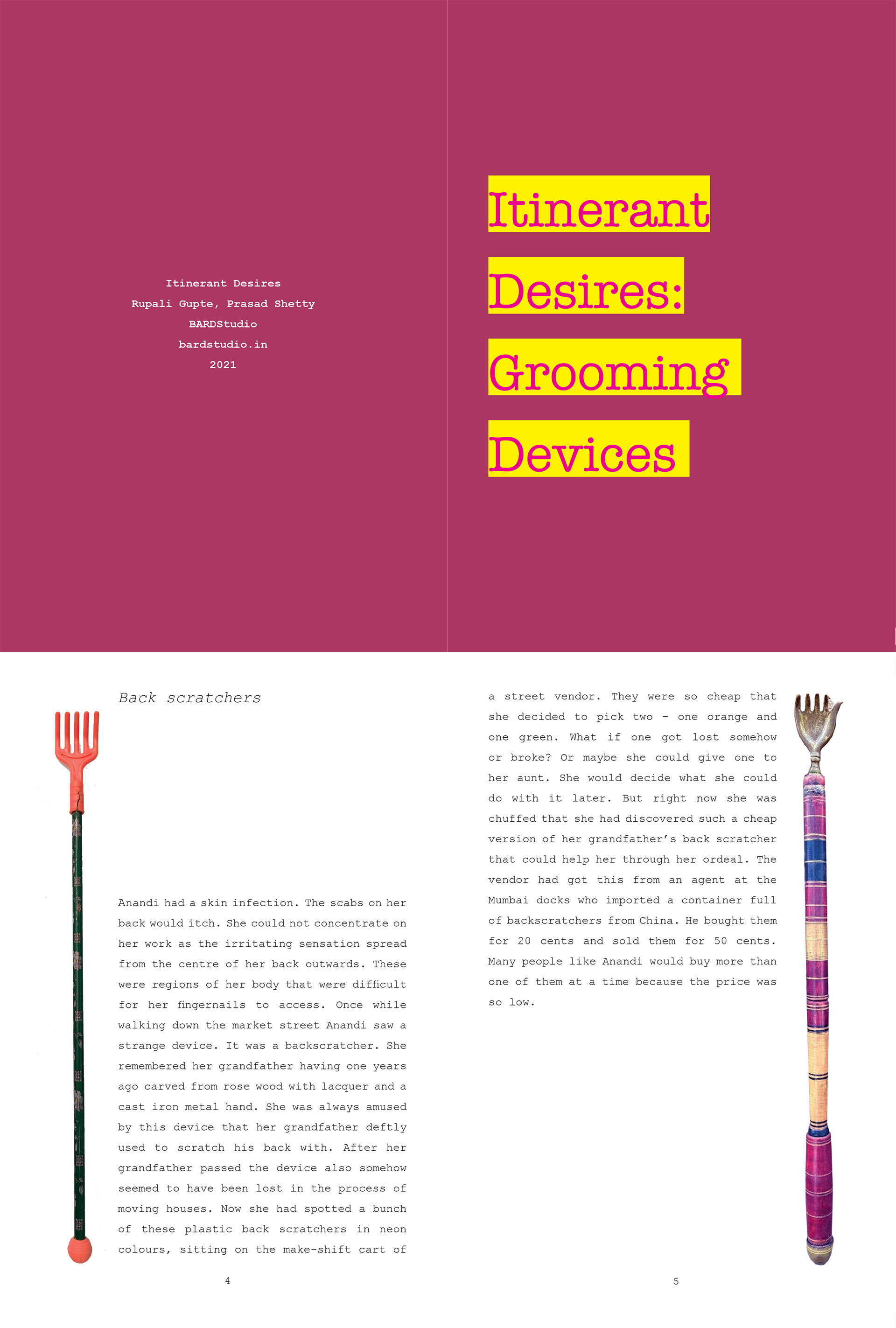

BARD Studio, “Itinerant Desires: Grooming Devices” (pages 4-5), 2020.

BARD Studio, “Itinerant Desires: Elephant God and Other Objects” (pages 8-9), 2020.

BARD Studio, “Itinerant Desires: Shoes” (pages 10-11), 2020.

BARD Studio, “Itinerant Desires Mobile Phones” (pages 4-7), 2020.

Rupali Gupte and Prasad Shetty are urbanists based in Mumbai, where they are co-founders of the School of Environment and Architecture and jointly run BARD Studio (f. 2016, India). Through writings, drawings, installations, mixed-media works, curation, storytelling, teaching, walks and spatial interventions, their research examines Indian urbanism with a focus on architecture, urban culture, urban economy, property, housing, urban form and entrepreneurial and tactical practices.

Curated by Aric Chen, with Martina Muzi, X is Not a Small Country – Unravelling the Post-Global Era includes nine newly created projects by international practitioners working across the fields of design, architecture and art who investigate, articulate and critique the current convoluted state of the world from multiple geographic perspectives.

In collaboration with maat, Art Jameel presents a series of moving image and video works, curated by Róisín Tapponi, in response to “Tactile Cinema” (2021), the site-specific installation by Bricklab, which offers a multi-screening space for filmmakers and visual artists from the Arab region.

The exhibition is accompanied by an editorial collaboration with e-flux Architecture entitled Cascades presenting original fictional writings that expand on the show’s themes while questioning what it means to speculate at a time increasingly defined not by linear narratives, but rather transactional opportunism, black swan events and unintended consequences.