Presented at maat in the context of the exhibition X is Not a Small Country (18/03–06/09/2021).

Tactile Cinema responds to Saudi Arabia’s three-decade prohibition on cinemas, which began in the early 1980s with the rise of hardline religious conservatism and lasted until 2018. Although films were aired regularly on satellite TV in cafes, restaurants and other spaces, it was the dark, acoustically insulated interior with stepped seating and ticketed entry that was deemed an illicit site of public gatherings. The site-specific installation by Bricklab highlights the cinema typology through form, enclosure and materiality. Its variety of seating and postural positions interprets some of the attitudes that Saudis adopted towards the space of the cinema before, during and after the ban. Meanwhile, its carpet patterning offers a textural translation of TV static – evoking a lost signal whose return many Saudis have waited patiently for.

View of the exhibition X is Not a Small Country – Unravelling the Post-Global Era with “Tactile Cinema” (2021) by Bricklab, with an installation of Wolfgang Tillmans’ posters in the back and BUREAU's exhibition design. Photography: Bruno Lopes. Courtesy of the authors and EDP Foundation / maat. Intro image: view of “Tactile Cinema” (2021) by Bricklab. Photography: Francisco Nogueira. Courtesy of BUREAU.

"Tactile Cinema", 2021

Wood, steel, carpet and screens

Site-specific installation, dimensions variable

Courtesy of the artists.

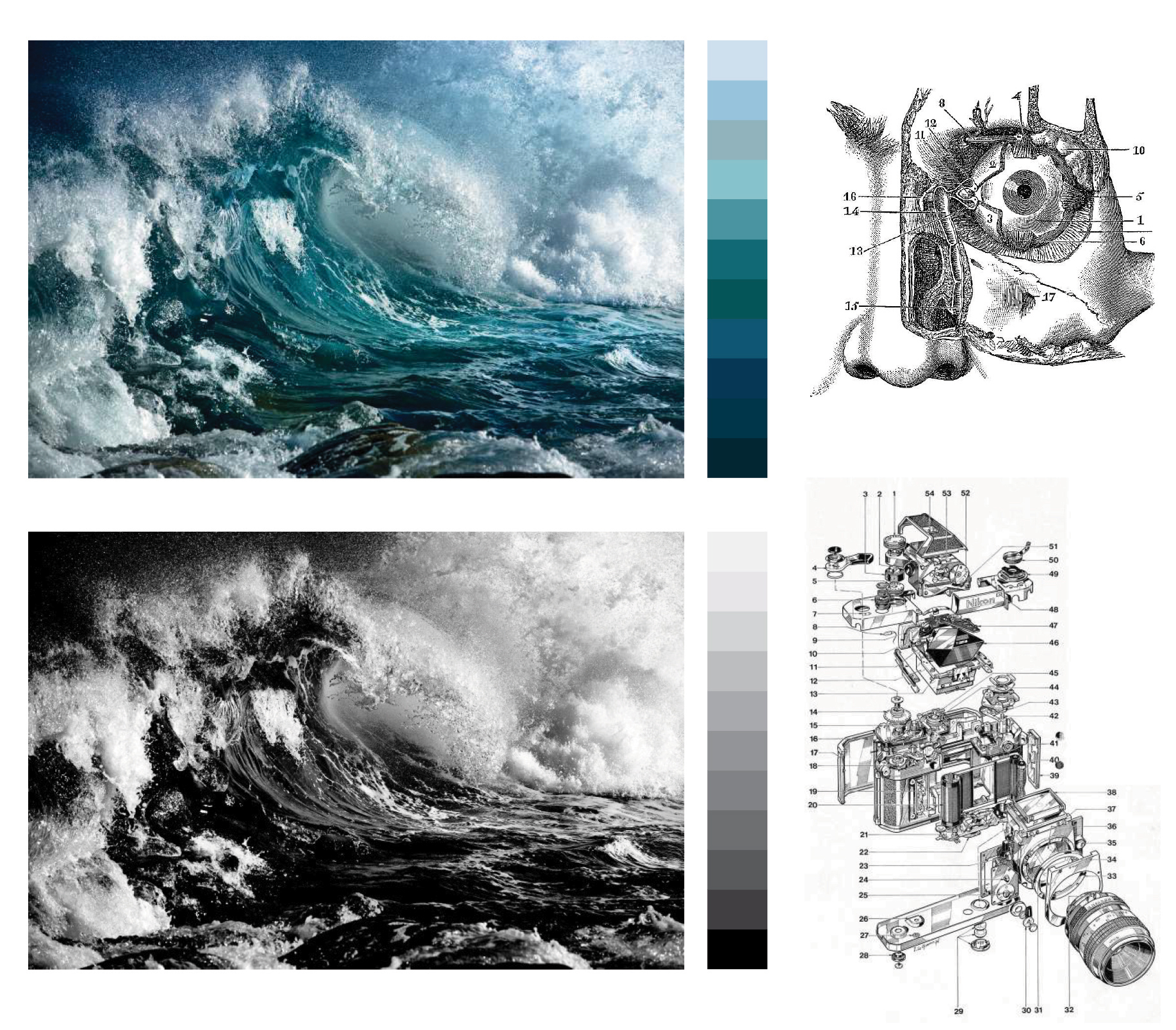

Tactile Cinema research imagery

Selection and captions by Bricklab

Architecture: Actor or Backdrop?

“The fascination with the dramatic, either in the program (murder, sexuality, violence) or in the mode of representation (strongly outlined images, distorted angles of vision – as if seen from a diving airforce bomber), is there to force a response. Architecture ceases to be a backdrop for actions, becoming the action itself.”

— Bernard Tschumi, Architecture and Disjunction (The MIT Press, 1994)

The “false” perspective in Andrea Palladio’s Teatro Olimpico (Vicenza, 1580–1585, here in a drawing by Ottavio Bertotti Scamozzi) allows the audience to indulge in the deceptive quality of the stage, whilst maintaining a critical understanding of the role of theatre in their collective cultural development. J. R. Eyerman’s iconic photograph (here in a coloured version by Bricklab) by used on the cover of Guy Debord’s Society of the Spectacle (Red & Black, 1970) tells a lot about the technological evolution of the cinema towards a more “truthful” representation of the “real”.

“The spectacle presents itself as a vast inaccessible reality that can never be questioned. Its sole message is: ‘What appears is good; what is good appears.’ The passive acceptance it demands is already effectively imposed by its monopoly of appearances, its manner of appearing without allowing any reply.”

— Guy Debord, The Society of the Spectacle (transl. by Donald Nicholson-Smith, Zone Books, 1995).

Cinema: between Culture and Entertainment?

Independent cinema and the triumph of the spectacle

Cinema is a powerful tool of deception. Its moving images simulate reality to the point where entire societies can be conditioned to believe in the messages, appearances and values communicated through this potent medium. Although Soviet Union propaganda films may seem more ideologically invasive, the same holds true for Hollywood productions.

Supported by a capitalist economy, mainstream film production can only rarely afford to deliver substantial content that transgresses the ethos of consumption. However, for its part, the independent cinema has limited stakeholders, a specific audience, and a more intimate showcase. As such, it gives the freedom to the directors, actors, scriptwriters to explore themes that can engage its audience beyond the mere entertainment. Film can move us beyond the simulation of reality to a conceptual space that allows us to reframe our experience of the world around us.

images

-

Teatro Olimpico (Andrea Palladio, Vicenza, 1580–1585). Drawing by Ottavio Bertotti Scamozzi.

-

J. R. Eyerman photograph published in the cover of “Society of the Spectacle” by Guy Debord, here in a coloured version by Bricklab. Courtesy of the artists.

-

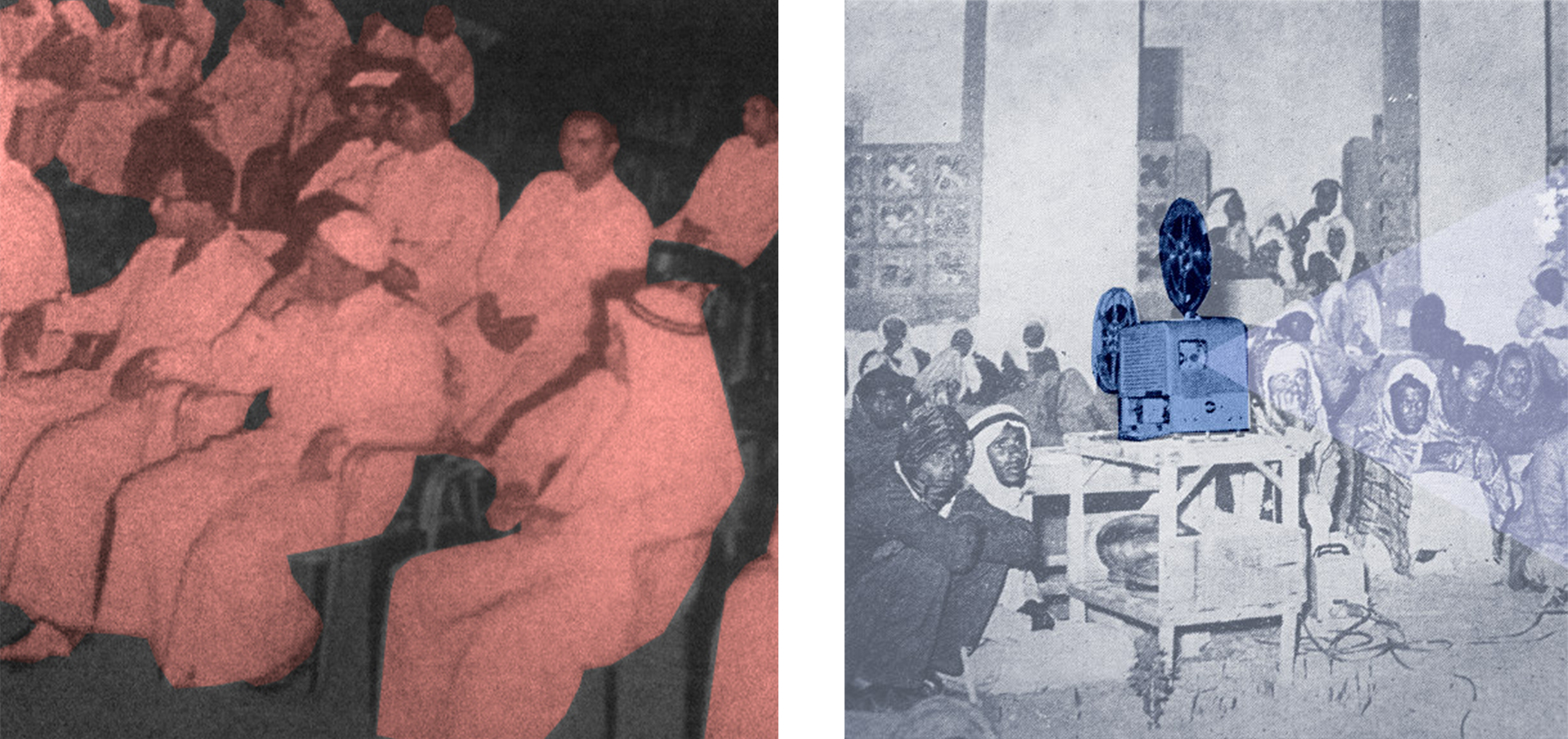

Garden cinema gathering. Courtesy of M. Sabbagh Archive.

-

Cinema session in the Nigerian Embassy in Jeddah, 1960s. Courtesy of Bricklab.

-

Sergei Eisenstein, coloured by Bricklab. Courtesy of the artists.

-

Static Tactility. Courtesy of the artists.

-

The Deception of the "Technical Image". Courtesy of the artists.

The Aesthetics of Static Signals

The past 40 years of the cinema ban has had detrimental effects on the film industry in Saudi Arabia.

Like a signal that has been abruptly cut off, much of the Saudi population waited patiently, even faithfully, for the signal to return. In the face of growing religious censorship, the creative class always maintained a sense of optimism towards their contribution to the film industry.

TV static is essentially a state of waiting between the receiver on earth and its satellite correspondent in space. It is a state which leaves the audience helpless if they cannot fix the signal themselves. Although the graphics of TV static may appear banal and meaningless, it is a state of noise and chaos in transition to order.

Hayy Cinema is planned to be the first community cinema that celebrates the revival of film industry in Saudi Arabia. As a turning point in the history of film making in the country, it shouldn’t shy away from its past and really celebrate this new era of cultural production.

The Deception of the "Technical Image"

“Colour photographs are on a higher level of abstraction than black-and-white ones. Black-and-white photographs are more concrete and in this sense more true: They reveal their theoretical origin more clearly, and vice versa: The ‘more genuine’ the colours of the photograph become, the more untruthful they are, the more they conceal their theoretical origin.

What is true of the colours of photographs is also true of all of the other elements of photographs. They all represent transcoded concepts that claim to have been reflected automatically from the world onto the surface. It is precisely this deception that has to be decoded so as to identify the true significance of the photograph …”

— Vilém Flusser, Towards a Philosophy of Photography (transl. by Anthony Mathews, Reaktion Books, 2000).

The deception of the technical image in coloured photography affords us the ability to equate it with lived experience. However, the resistance of the black-and-white image incessantly reminds us of the abstraction process of its mechanical production. This duality of perception is used in this design proposal to contrast the grey scale interior of the cinema space with the colourful real world outside it.

View of the exhibition X is Not a Small Country – Unravelling the Post-Global Era with “Tactile Cinema” (2021) by Bricklab, with an installation of Wolfgang Tillmans’ posters in the back. Photography: Bruno Lopes. Courtesy of the authors and EDP Foundation / maat.

Bricklab

"Tactile Cinema", 2021

Wood, steel, carpet and screens

Site-specific installation, dimensions variable

Courtesy of the artists.

Interview with Abdulrahman and Turki Gazzaz (Bricklab)

by Aric Chen and Martina Muzi

Aric Chen / Martina Muzi

Many people outside of Saudi Arabia have long assumed that it was film itself that was banned, not just cinemas. But as you’ve explained, during the ban, films could still be shown in homes, cafes and so on. In other words, it was not the medium that was forbidden, but rather the public spaces for it. Can you elaborate on this, and how you would describe the “improvisational” or “informal” cinemas that arose as a result?

Bricklab

The official ban on cinemas was implemented following the 1979 siege of Mecca, with the rise of an ultra-conservative movement that was against the social and ideological manifestations of modernisation. As part of this, a specially appointed religious police force was tasked with implementing a strict code of conduct in public spaces to homogenise the outward appearance of Saudi society in an effort to combat Westernisation.

However, their sphere of influence did not extend to the private affairs of citizens. Within this context of nuanced interactions and ambiguous laws, the private nature of satellite television exposed the local community to global media. So, while the local film industry suffered severely, Saudis still managed to find alternatives in the absence of cinema as a public institution. Private homes, offices, consulates, and sometimes cafes would host screenings for a limited audience. This process generated an intricate gradient between public and private spaces and their perceptions for Saudi society. The informal spaces that resulted created resilient communities determined to pursue film as a medium for cultural expression against all odds.

Aric Chen / Martina Muzi

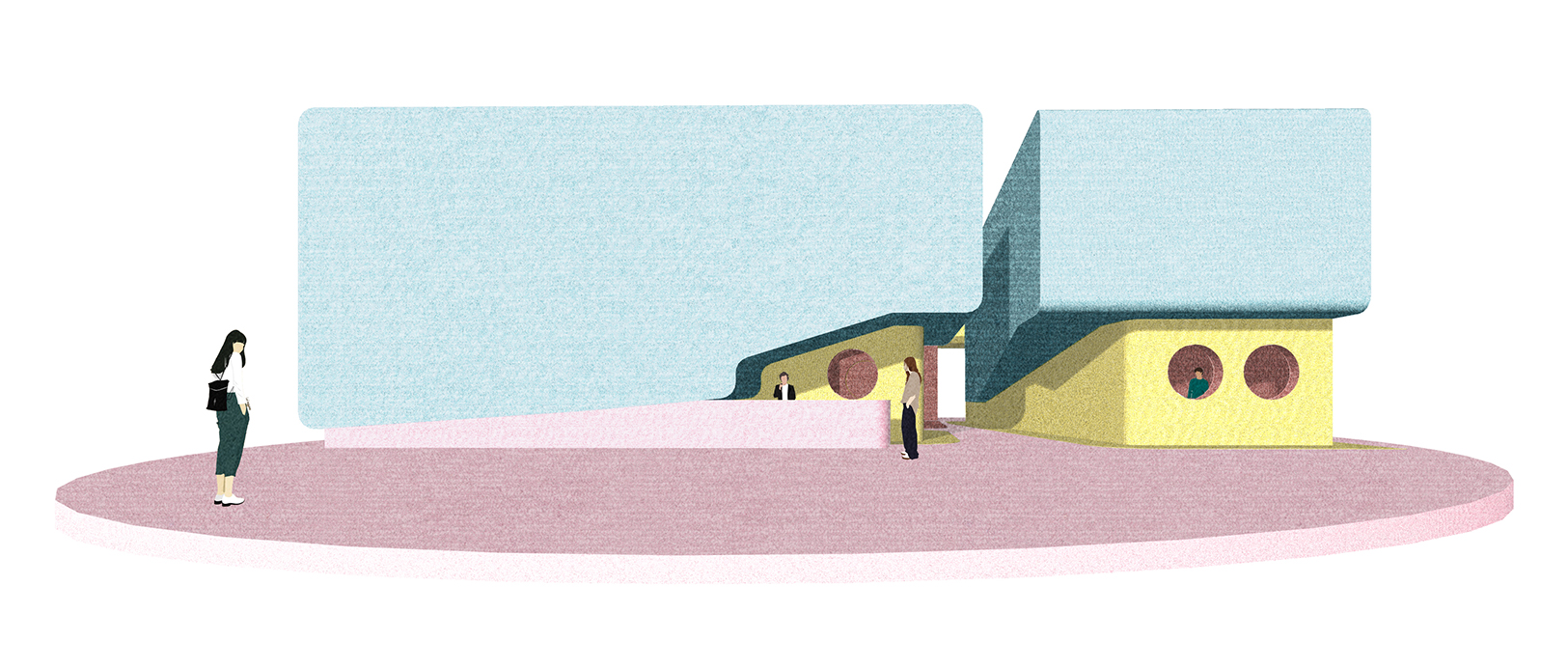

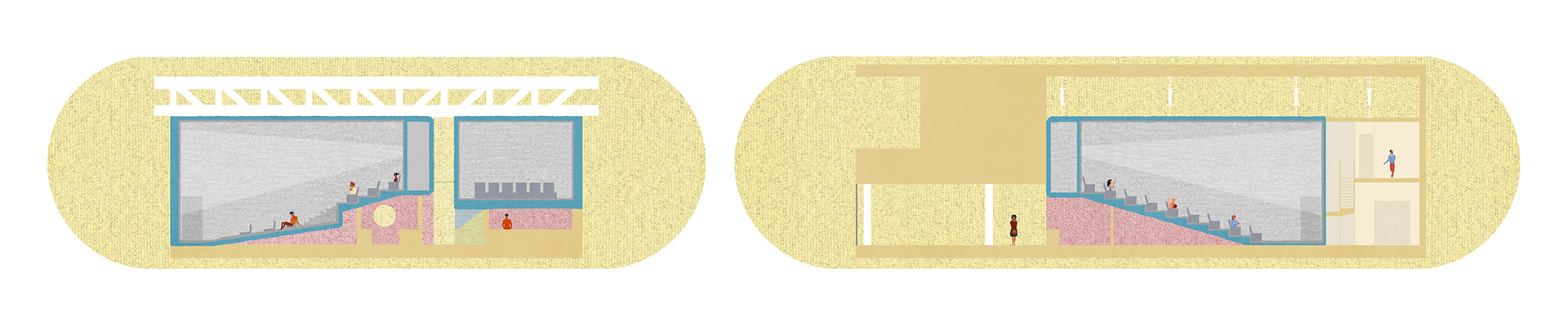

Tactile Cinema is a further exploration based on the theatre you’ve designed for Hayy Jameel in Jeddah, a contemporary culture venue currently being built by Art Jameel. Can you describe the relationship between these two projects?

Bricklab

Hayy, which means “district” in Arabic, connotes a notion of place and community, an attitude adopted from the outset with the Creative Hub, which called for an independent arthouse cinema.

It started not long after the ban on cinemas was lifted, and the film community – actors, producers, writers, directors – found themselves in a situation where the infrastructure for the industry didn’t really exist. They needed screening spaces, archives, literary material, and most importantly, an institution to support them. As architects, we began questioning our role and how we could cater to them. So programmatically, we expanded the scope of the competition to include the facilities required to foster a thriving community.

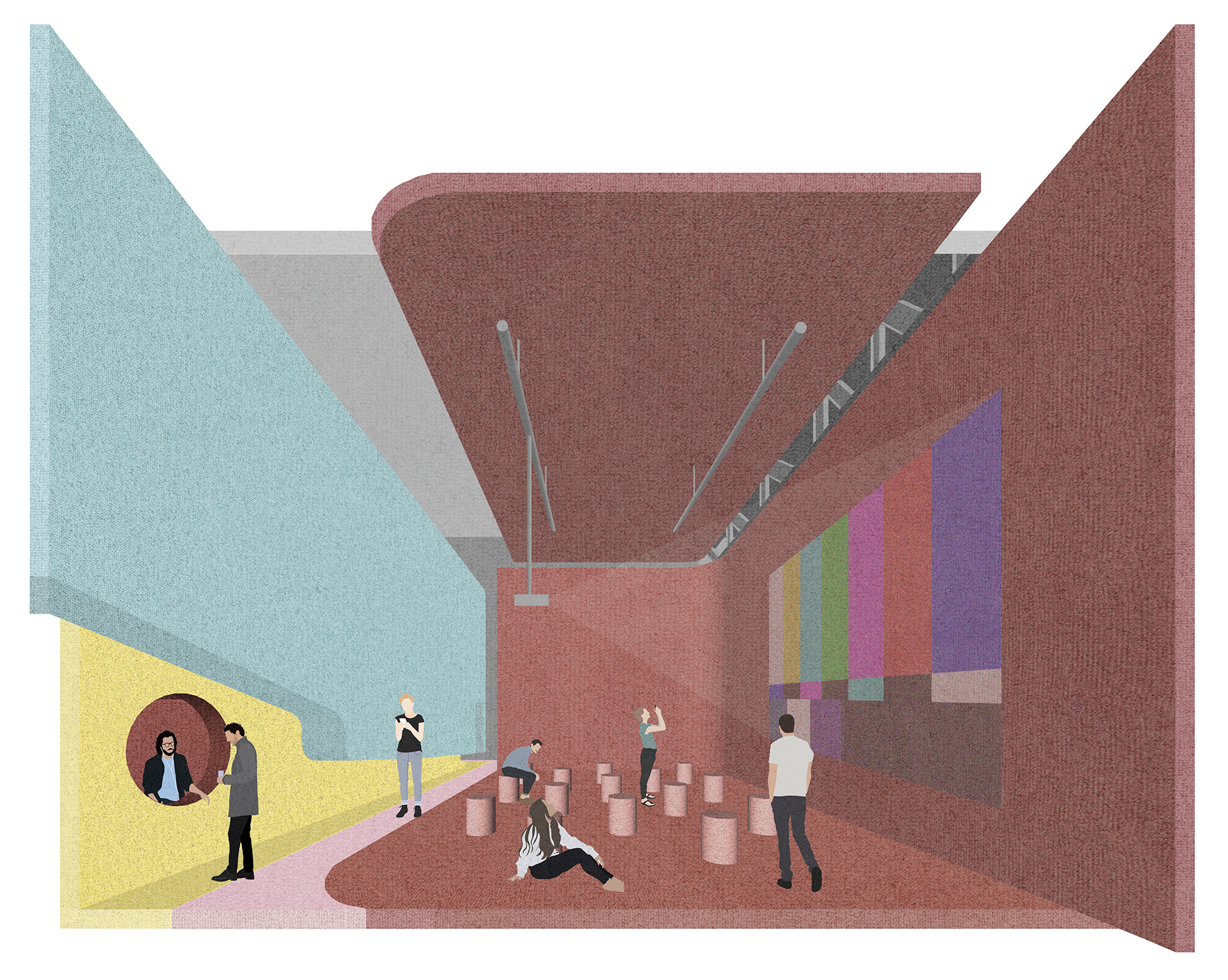

In terms of design language, we wanted to emphasise this critical moment when a vacuum was clearly sensed as soon as the ban was lifted. If we were to examine the history of cinema in the country, the ban may be read as an interruption to an otherwise continuous transmission. This led us to investigate TV static as a visual and tactile interpretation of this narrative. To symbolically refer to this common visual language, we used carpet as a tactile manifestation that we employed throughout the space to establish a strong design character and relatable narrative for the newly founded community.

For maat, we wanted to further explore ideas about form, posture, enclosure, and material in a context that is less rigid than an interior architecture project. X is Not a Small Country allowed us to continue our experimentation while communicating the cultural transformations that are taking place locally to a wider audience.

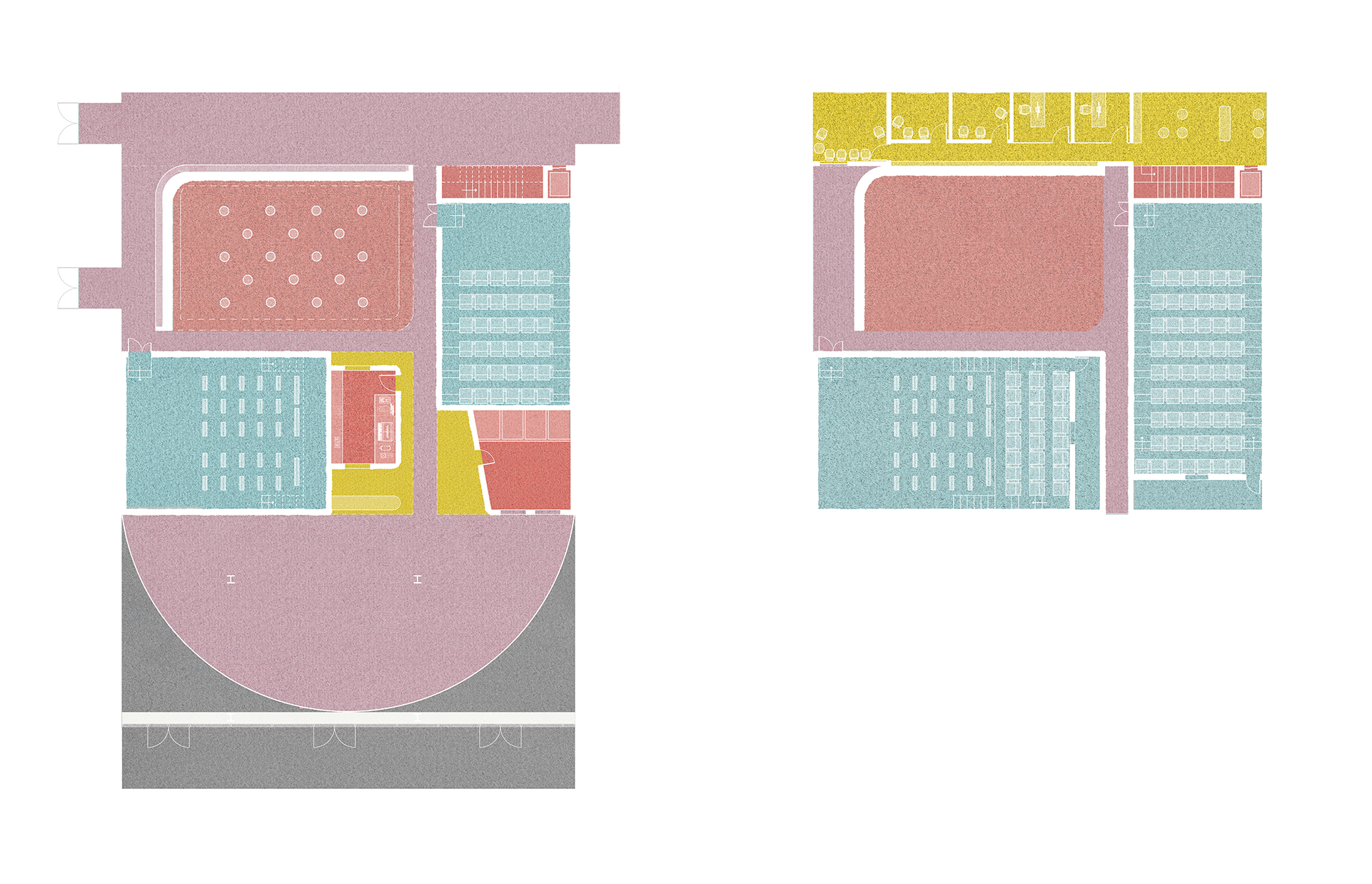

Bricklab’s Hayy Cinema at Hayy Jameel | Art Jameel, Jeddah, in different drawings. All images courtesy of Bricklab.

Aric Chen / Martina Muzi

Tell us more about how Tactile Cinema does this.

Bricklab

In manifesting the shifting attitudes towards cinemas in Saudi Arabia, we employed posture and enclosure as variables to generate the three distinct screening spaces that comprise the installation. We generally started thinking of them as spatial time capsules that literally trace out an early diagram. Each space represents a time period. The forum in the middle is completely open, with amphitheatre seating referencing the recent lifting of the ban. On the other end of the spectrum, the fully isolated single occupancy space utilises the same proportions of a classic cinema chair to simulate the private screening spaces during the ban. The third space is semi-open with a reclined seating setup and an unconventional method of entry, as an homage to the improvisational spaces of cinema al-housh [informal backyard cinemas] and later modifications adopted during the ban.

Aric Chen / Martina Muzi

The cinema ban was lifted in 2018, and Saudi Arabia has since seen a rapid proliferation of cinemas. The government has even launched a Red Sea Film Festival, whose venue you partly designed (though its first edition last year was cancelled due to the pandemic). Besides the obvious – more cinemas – how else might the various ways in which the country is changing impact architecture and spatial typologies?

Bricklab

Saudi society has changed dramatically in the past few years. Theatre, cinema, performance venues, and popup events began to proliferate across the country, challenging our understanding of public space. The direct effects of these changing attitudes have already impacted the disciplines of architecture and planning. The various megaprojects across the nation are increasingly focusing on quality of life, public space and cultural expression, and architects are being engaged to explore these new spaces and encouraged to involve their respective communities from the design stage onwards.

Bricklab’s “Tactile Cinema” (2021) installed in the exhibition X is Not a Small Country – Unravelling the Post-Global Era. Photography: Bruno Lopes (left) / Francisco Craveiro (right). Courtesy of the authors and EDP Foundation / maat.

Aric Chen / Martina Muzi

As architects, do you see any drawbacks or risks in the ways that Saudi Arabia has been changing?

Bricklab

As a small experimental office, we have actually seen an influx of interest in the local design industry like we have never seen before; this offered the opportunity for us to research and study our cities through competitions and commissions that vary in scale from master-planning to small scale interior spaces or even objects.

Aric Chen / Martina Muzi

What’s next for you?

Bricklab

Aside from our architectural projects, we are working with Athr Gallery and Khabar Keslan on a screen-printed publication with the help of Misht Studio. Called Raw: Print, it aims to promote cross-disciplinary engagement between art, architecture, design and a wider set of disciplines that influence cultural production. We are also working on an exhibition, opening in June, called Saudi Modern: Jeddah between 1938–1963, for which we are reiterating the historical narrative of modernism in Jeddah in one part, and engaging with eight artists to create an expression of the time in the other.

Based in Jeddah, Bricklab (f. 2015, Saudi Arabia) was founded by brothers Abdulrahman and Turki Gazzaz in 2015. The multidisciplinary architecture studio examines design as a vehicle that intersects with the social, political, economic and cultural networks that implicitly form our built environment. It represented Saudi Arabia in the country’s first-ever national pavilion at the 16th Venice Architecture Biennale in 2018.

Curated by Aric Chen, with Martina Muzi, X is Not a Small Country – Unravelling the Post-Global Era includes nine newly created projects by international practitioners working across the fields of design, architecture and art who investigate, articulate and critique the current convoluted state of the world from multiple geographic perspectives.

In collaboration with maat, Art Jameel presents a series of moving image and video works, curated by Róisín Tapponi, in response to “Tactile Cinema” (2021), the site-specific installation by Bricklab, which offers a multi-screening space for filmmakers and visual artists from the Arab region.

The exhibition is accompanied by an editorial collaboration with e-flux Architecture entitled Cascades presenting original fictional writings that expand on the show’s themes while questioning what it means to speculate at a time increasingly defined not by linear narratives, but rather transactional opportunism, black swan events and unintended consequences.