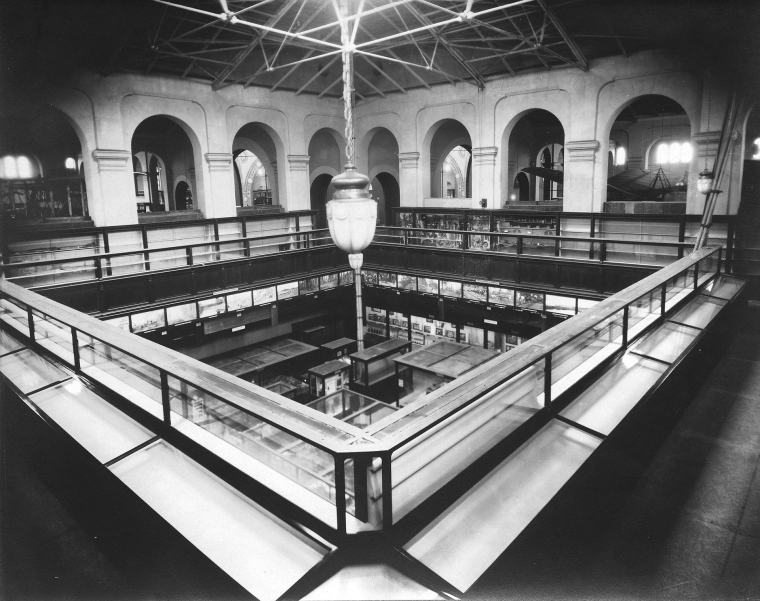

Empty exhibit cases at the United States National Museum, now known as the Arts and Industries Building, 1880s, USA. © Smithsonian Institution Archives. Image # SIA-MAH-24059.

On 2 March 2021, we had a (private) Zoom conversation with Ana Balona de Oliveira, researcher and independent curator. Moderated by Susana Pomba, participants included Susana Gaudêncio and Maribel Mendes Sobreira. The Zoom conversation was later transcribed, edited, and then reviewed by the interviewee. This is the third of a group of three conversations included in Empty Exhibit Cases, a project that gathers three cisgender white women working in the arts, on their way to become life-long anti-racist and effective allies as artists, teachers, researchers, curators, historians, writers or authors.

Susana Pomba

How did your career develop? How did you find your beliefs, your interests, and your area of study?

Ana Balona de Oliveira

My professional life has been quite academic, I am a researcher. I did a master’s, a PhD and a postdoc and now I am a hired researcher at Nova FCSH’s Art History Institute [Lisbon]. In my graduate studies, I started with philosophy and then specialised in aesthetics, politics and ethics. Those philosophical themes are still important in my work – aesthetics and political ethics – but in philosophy I felt very distant to artistic practices. I felt I needed to be closer to contemporary practices, which took me to modern and contemporary art history. When I was still studying philosophy, my experience abroad with the Eramus programme was intense and important, but in a place with which I didn’t identify much: Switzerland. I chose to go because there were not many options, and I remember thinking very strategically, “It will be good to travel”, because it was a very central location. Then I went to London for my master’s, a possibility that seemed very interesting to me, in terms of language, academia and art. Many Portuguese, some with limited financial means, chose the city to study and work (we should say that there are several migratory fluxes, and the question of privilege comes in, which I am sure we will address later). At first, I had some support from my family, later I found jobs there and got research grants. A trip that was supposed to last one year ended up lasting almost a decade: I lived in London for nine years.

Susana Pomba

Which university did you chose for your master’s?

Ana Balona de Oliveira

The Courtauld Institute of Art, a part of the University of London that specialises in art history. I was in the modern and contemporary art research area, and I did my master’s with Mignon Nixon, an American academic working in London and an editor for October journal. Between my master’s and PhD, I took a break and worked in the commercial gallery circuit, in a small gallery in the East End, in the Brick Lane-Bethnal Green area, which had an influence on some of the curatorial activities that I developed later when I left the gallery. That moment was important, because I met a lot of people, young artists and curators. With friends I met at the time, I formed a curatorial collective: the Five Storey Projects with which I collaborated on some projects.

Susana Pomba

So, it was in London that you started to curate exhibitions.

Ana Balona de Oliveira

Yes. In a non-commercial way, within the scope of collectives and in places that were squatted. I arrived in London at the end of a very strong squatting movement (and a rise in gentrification), but I still lived it partly, it was still possible to occupy some spaces that were not mainstream and make some interesting projects in a city with many artists, young curators and writers coming out of university and beginning to try out things collectively. That experience in the gallery was also important to understand that it was not in the commercial gallery system that I wanted to work. Then, I started my PhD, which from a theoretical point of view, partly followed my master’s: in the beginning still not very postcolonial, but already with a strong focus on feminism, one of Mignon Nixon’s specialities. She is an art historian specialised in a feminism, very influenced by the North American scene, especially the 1970s in New York – it’s during this time that I found artists like Adrian Piper and Yayoi Kusama. Some of those artists already worked in a somewhat intersectional way. In terms of theory, my master’s was psychoanalytical and poststructuralist: a lot of psychoanalysis, Foucault, Derrida and a lot of feminist theory. But we hadn’t approached the feminisms of the Global South: we studied plural feminisms but not through a postcolonial/decolonial scope, which several Black academics in the UK were already doing. I discovered those subjects right after that, in the first year of my PhD.

Susana Pomba

So we situate ourselves in terms of dates. When did you start your master’s and PhD?

Ana Balona de Oliveira

I started my master’s in 2006 and my PhD in 2008. Initially, my PhD project focused on women artists from different origins. I was very interested in thinking about displacement and moving in contexts of violence. But in fact it was too grandiose because I had to deal with and study many geopolitical contexts in depth. South Africa and Ângela [Ferreira] were already included but also a series of other contexts like the Middle East and Latin America. I had to narrow it down and it was then that I realised that Angela’s work – its focus on transitions and displacements between South Africa, Mozambique and Portugal – provided enough material for a thesis. My master’s was about New York artist and theorist, Silvia Kolbowski, born in Argentina of Polish and Jewish descent. Her work is very connected with archive and memory, and actually I continued to pursue those subjects throughout my PhD. It was then that I started to focus on very specific archives, colonial, anti-colonial and postcolonial archives, and other related archives: South African apartheid and post-apartheid archives, the memory of the Estado Novo [New State], the revolution and the post-revolution in Portugal. All of this with Ângela’s work as a starting point. Compared with other women artists, her work was not as studied, internationally or in Portugal, a country where she was a pioneer in dealing with a series of issues, making her home in Lisbon in the 1990s. It was actually at that moment and with her work that a postcolonial reflexivity developed in the visual arts. At the time, there was [António] Lobo Antunes in literature, some cinema with Fernando Matos Silva, João Botelho and others. Ângela participated in another important way as a teacher of younger generations at Ar.Co [art school].

Susana Pomba

And the Faculty of Fine Arts in Lisbon.

Ana Balona de Oliveira

Ar.Co first and then the Faculty of Fine Arts. That role was also important in the way a series of issues started to be approached by younger generations. She tells the story that when students graduated and asked for advice, she would say, “go abroad” or “go to the Maumaus [School] study programme”. And actually, many did. Also, from a theoretical point of view, Ângela is quite an anglophile, due to her South African academic experience. She came equipped with postcolonial theoretical tools that were used very little in Portugal. I think it was that, coming from South Africa, which gave her quite a unique position but also, for quite some time, a very solitary one. Her work only broke through later because in the 1990s these issues were not “fashionable” in Portugal. Despite that, around the same time some relevant initiatives occurred, for example the exhibition 15 South African Artists: Don’t Mess with Mr. In-Between, curated by Ruth Rosengarten with curatorial assistance by Ângela Ferreira (Culturgest, 1996). It’s also important to recognise the work of people like Manuela Ribeiro Sanches at the Faculty of Humanities of the University of Lisbon; José António Fernandes Dias at Africa.Cont; the Maumaus School; António Pinto Ribeiro’s programme at Culturgest [Uma Casa do Mundo] and Gulbenkian [Próximo Futuro], etc.

Susana Pomba

What was the connecting point between the curating you did in London, which was more collaborative, and the curating projects that you’ve done in Portugal?

Ana Balona de Oliveira

Actually, I had to slow down my curatorial practice in London because of my PhD and the important trips to Portugal, South Africa and Mozambique that it demanded. When I came back to Portugal for my postdoc (that I started in 2013), there was research done and a close relationship with Ângela Ferreira that went beyond my PhD. In 2014, an opportunity came up to curate her work. I was invited by CAAA [Center for Art & Architecture] in Guimarães to make a solo show of her work called Monuments in Reverse, which happened in 2015. This project was the seed for a larger solo show, Underground Cinemas & Towering Radios, that I also curated in Lisbon at Galeria Av. da India in 2016. The way I curate mainly comes from my research, but the research is always my main activity. I really like the curatorial exercise but for me it is really just another way to research. It comes from that line of thought.

Susana Pomba

How do you measure things? As White curators and researchers, we have to admit that we make mistakes, that that is part of developing. But how do we know that we are not acting with White privilege, that we are not falling into the trap of being the White saviour, that we are not falling into the trap of cultural appropriation and “using” in an inappropriate way? These are all questions I ask myself as a curator. You have more experience with these matters, where do you stand in order not to fall into bad habits in this overwhelming field of White privilege?

Ana Balona de Oliveira

I think it’s a vigilance that you practice, but it’s ongoing. We are learning constantly, the risks are always there, and actually, it happens all the time because it’s so engrained, we have been socially instructed in such a racist way, it’s unavoidable. Just think about the schools we went to, the books we studied from, I am speaking for myself, of course, and I totally recognise it was a racist and sexist education.

Susana Pomba

We all had that education I think. But the experience of travelling that you did clearly opened your horizons, it gave you a different foundation.

Ana Balona de Oliveira

Yes, for me the learning truly started in London. Even though the situation in the UK is still not egalitarian, academia is structurally still White, it is still a very racist country, but there is a very strong Black academia and Black critical mass. I wandered around and looked for events, talks and seminars that were related with these issues of migration, identities, postcolonial, diasporas, Black Britain, Black Europe, the history of Black British modernism. I studied all of these within the scope of my PhD. I worked in British academia and in the British artistic circuits, keeping up and attending debates, reading specifically about Black feminism. Afterwards, I critically thought about whiteness too, in other contexts, concerning which there are parallels with my own London experience, but also a lot of differences and specificities. It’s very different to talk about racism in Luanda, Maputo, Johannesburg or Cape Town. Traveling gave me a certain sensibility, to understand certain differences: for instance, a discussion about racism is different for a Mozambican artist that lives in Maputo than for a Mozambican artist living in Europe – the terms of the discussion change. London was fundamental for my political beliefs. That was where I found out I was White, for starters. When I came back to Portugal, I carried that education with me.

I remember, for example, some controversies that happened in London concerning curatorial projects, like Brett Bailey’s Exhibit B, a White South African artist. His show had already toured some European cities. When it arrived in London in 2014, the Black community – academic, artistic and activist – was so radically opposed that the exhibition simply didn’t open at the Barbican. In the UK, despite all the problems, Black movements have had that power, the capacity to mobilise and pressure.

Susana Pomba

It was a commentary on human zoos and ethnographic displays, a “living” museum. Something extremely shocking but one with a clear objective.

Ana Balona de Oliveira

With the best of intentions, the artist wanted to denounce these practices but without thinking of the critical limits of the re-enactment, without enough questioning. The question of legitimacy should also be raised here: was it his place to do this? Was it his place to take the lead in this way? Influenced by the Brazilian context, this question of legitimacy is quite debated today starting with the idea of a place of speech [Djamila Ribeiro] which, in anglophone terms, was developed around the idea of enunciation, the positions of identity concerning enunciation and representation [Stuart Hall], of “who can speak?” and the subaltern [Gayatri Spivak].

Maribel Mendes Sobreira

Concerning the “place of speech”, in this case it is a South African White artist, so he can easily fall into a paternalist mind set.

Ana Balona de Oliveira

The issue of paternalism is one of the great dangers, without a doubt.

Susana Pomba

How do you see these discussions today within the Portuguese contemporary art world? I think there is a lot of reluctance, a lot of work to do.

Ana Balona de Oliveira

We need more Black voices. The changes have to be structural. For instance, in my research groups [Visual Culture, Migration, Globalization and Decolonization, till 2018 and currently Transnational Perspectives on Contemporary Art at IHA-FCSH-NOVA], we all have the best of intentions, we are all trying to work in the most critical and conscious way as allies. But we have to be careful with these good intentions and alliances because of the constant risk of paternalism. The risk is always there and structural and systemic changes take a long time. When compared with the British context, we are decades behind . Therefore, structural changes will have to happen, in education for instance, so that intime, there can be more Black art historians. I don’t have any Black colleagues researching in my university. Fortunately, there is more and more people in sociology, in political science, there are also artistic voices, but in art history and curating…

Susana Gaudêncio

There are no Black voices in curating, working regularly.

Ana Balona de Oliveira

No, not even working in museums, especially in management positions. That is where the structural question comes in, who can access education. For Black students that reach schools, segregation starts very early on, and many don’t reach university. For example, I was teaching some classes at Nova University, it was the first year and I wanted to introduce some elements about decolonisation and against the Eurocentric canon of art history. Most of the students were White. There was only one Black student that came from a history course and had taken the subject as an optional class. A structural change is necessary at every educational level so that there is real equality in accessing an artistic career, in art history and in curating. We need more Portuguese Black men and women in higher education in these areas.

Susana Pomba

And to be talking about contemporary art seems to be a luxury, the choice to attend university is not even there. It is a very closed milieu.

Ana Balona de Oliveira

Yes. There is activism and grassroots movements but artistic practice and the elites tend to be close to one another, at least in a certain Western or westernised way. There are, of course, traditions in artistic practices in other contexts, with another history. In the European context, the history of artistic production is very close to circuits of power (even though it is also connected with many struggles). It is through access to education and politics that change happens. In the last few years in Portugal, there was an important effort to intensify the debate in the arts, activism and academia (for me these two areas are very interconnected). Due to president Lula’s quota programme, many Black Brazilian researchers and artists reached universities in Brazil and then afterwards came to Portugal for Sandwich PhD Programmes. Some stayed here, others returned. Some Portuguese complain about supposedly a more combative tone. I don’t complain; it is a necessary and important phase in fighting these issues. Which is to say that we owe a certain strengthening of a Black voice in Portugal (maybe more in Lisbon) to president Lula, because we feel the impact of those more politicised voices in academia, in the Black movement and in the arts.

Susana Gaudêncio

There is a strong presence of that community in the master’s at the fine art school in Porto where I teach, in which most students are Brazilian. They have a completely different openness, intelligence, and knowledge when it comes to intersectional feminism, anti-racist issues and different connections to education and art. An openness that Portuguese students don’t have. In Porto, there is also a large community of Brazilian immigrants and in an interesting way that is mirrored not only in visual arts but also in architecture. I also teach in Caldas da Rainha, near Lisbon, graduate and master’s degrees, where there isn’t such a great presence of this community, and there’s more reluctance in addressing these issues.

Ana Balona de Oliveira

Yes, and many of those voices come for a PhD, they arrive with experience in activism and feminism, and they organise. For example, there is an International Film Festival in Cova da Moura, a festival of Black cinema, organised by Maíra Zenun and Luzia Gomes. Meanwhile, she has returned to Brazil, but Maíra has stayed in Portugal. There are organisations, activities, and events being created, which have produced effects and contributed to change, radicalising speech in a positive way while bringing up uncomfortable subjects. Just the presence of Black bodies in some artistic and academic spaces is in itself a statement, because of how White these spaces have been until recently. This change is recent and important, and it has been carried out by the Black movement – actually they have had a long history in Portugal but it has always been made invisible, with some White allies – for instance, in some parts of the media, like Joana Gorjão Henriques’s coverage in the newspaper Público. Today, there are some Black voices with more visibility in public space, parts of the media, parts of academia, even though still very little. Still, it’s important to highlight the work of figures like sociologist Cristina Roldão, MPs Joacine Katar Moreira and Beatriz Gomes Dias, and the work of activist Mamadou Ba. They are here to stay in public space. I would say, following the work that these activists and academics do, something that is fundamental to beginning to structurally change the state of things is to collect ethno-racial data. It might seem like something that has nothing to do with the arts and with what we are talking about but it has; we need it to understand why we don’t have Black museum directors, or academics, curators, etc.

Susana Pomba

It’s a huge problem. As you were saying, dismantling starts with education. But I question our very small contemporary art scene. Performative arts in Portugal are very strong, more collective, they organise themselves more. That doesn’t happen in visual arts. How can we be good allies?

Ana Balona de Oliveira

Alliances are also a complicated matter. I keep hearing the thoughts of several Black colleagues, they have a generosity in sharing with us their frustrations of working with White allies, because we are very used to a certain leading role, and I think that is what we have to learn. I speak for myself; concerning certain modi operandi, I think that at many levels the strategy has to be to retreat. To know when to say no, to know when to abdicate that leading role. There are a series of things I want to do and would like to do and, today I think twice. The question of doing it or not and with whom is fundamental, not only from the point of view of who you are inviting but also from the point of view of the logic of organising and programming itself: who does the programming? Who makes the invitations? It’s important to invite Black voices but it’s also important to think how we can have a horizontal presence, as much as possible, at the level of the organisation itself.

Susana Pomba

What do you mean by horizontal?

Ana Balona de Oliveira

We have to be careful in the way we organise events, the way we gather teams, the way we organise the work collectively within those teams. Who stands at the forefront at this or that specific moment. Then, it’s about who is this team going to invite. We need to think about how to do it, with whom, in what way we can do it together. We might even conclude that it’s not up to us to do it at all. When it comes to who is invited or who develops the idea of organising something.We have to engage in dialogue as much as we can and in the least imposing way possible. There is the danger of tokenism, also of the paternalism we referred to before, but at the same time we have a huge responsibility of not making Black people invisible, of not ignoring the necessity of representation. It’s a question of power: do we only act in our own terms or in the terms of the people we want to bring on board? That’s when we really need to listen and be willing to give in.

Susana Pomba

It’s a relationship that has to be created and managed every day.

Ana Balona de Oliveira

It’s also important to understand refusal, if it happens. I understand very well the apprehension that People of Colour have of just being a means to an end, of “ticking of the box”, without altering structural power dynamics.

Susana Pomba

Of course. Not wanting to be some sort of trophy.

Ana Balona de Oliveira

It is a very legitimate fear. Hence the importance of relationships based on trust and a very honest dialogue.

Susana Pomba

To be very up front and honest.

Ana Balona de Oliveira

If we have the funds, for example, when we establish partnerships, the process might entail not taking the decision making power. I have these funds, I want to make this partnership happen, so I might give the power to this partner, to this organisation, that will know more and do better.

Susana Pomba

Thinking about issues of gender, in parallel with issues of race. How can we contribute to the inclusion of women artists in Portuguese art history, in thought, in criticism, in writing?

Ana Balona de Oliveira

There is a lot of work to do on several fronts. We have to think about who is absent. There are a lot of forgotten women artists in Portugal, mainly White, which immediately raises the question – an update to the famous Linda Nochlin question [Why have there been no great women artists?]– “Why weren't there more Black women artists?” It’s necessary to think about the structural reasons for that. My colleagues Giulia Lamoni and Vanessa Badagliacca did that in part in an exhibition about eco-feminism, Earthkeeping, Earthshaking – Art, Feminisms and Ecology, which they curated at Quadrum Gallery,and included Portuguese artists from the 1970s up to now. The effort toward inclusion should be doubled. Grada [Kilomba] talks about this in her book, inspired by bell hooks: the idea that it’s important to occupy spaces of power without abandoning the margins and without fetishising both. It’s a fact that it is necessary to open and democratise the canon, expand it and this means to create a narrative around what was forgotten. For instance, to choose to write about a woman artist and not a man artist, to write about a Black woman artist instead of a White woman artist, to choose who you write about, who you select for an exhibition, those are gestures that are already giving visibility and engaging with history. Grada also highlights the productive dimension of living in the non-mainstream, of how a lot can be done, for instance, outside the space of the museum and gentrified spaces in the city centre, of how it can be more relevant to work in peripheral spaces in a grassroots way. At the same time, she also highlights the danger of exoticising the margin, for instance, someone with no connection to a certain neighbourhood and community going there as a White saviour. We need to be careful where you go, and how you go in. Which is to say, it is necessary to work on several fronts, opening the canon and working outside of it. This double strategy can be made possible through several ways: we can curate without neglecting smaller, more alternative and less mainstream spaces; publish without neglecting less hegemonic ways of publishing; organising events in a less academic way. I try to maintain this parallel logic. We are pressured to publish in peer-reviewed magazines with restricted access, which tends to keep our research in ivory towers. We have to fight for open access, for more democratic platforms, and again, as horizontal as possible. On the other hand, occupying hegemonic spaces is not necessarily bad, on the contrary, it is necessary in order to disturb engrained power dynamics. It’s good that certain voices reach television and newspapers and don’t only occupy the space of a fanzine. But we are not going to neglect alternative circuits of publishing, exhibiting and discussing. There are several strategies for a more democratic art history: it should happen in academia, in publishing houses. The spaces of power should be occupied, yes, but without forgetting the alternative spaces and, on the other hand, remembering the danger of fetishising both the margin and the centre.

As White curators and researchers, we have to admit that we make mistakes, that that is part of developing. But how do we know that we are not acting with White privilege, that we are not falling into the trap of being the White saviour, that we are not falling into the trap of cultural appropriation and “using” in an inappropriate way? These are all questions I ask myself as a curator.

Susana Pomba

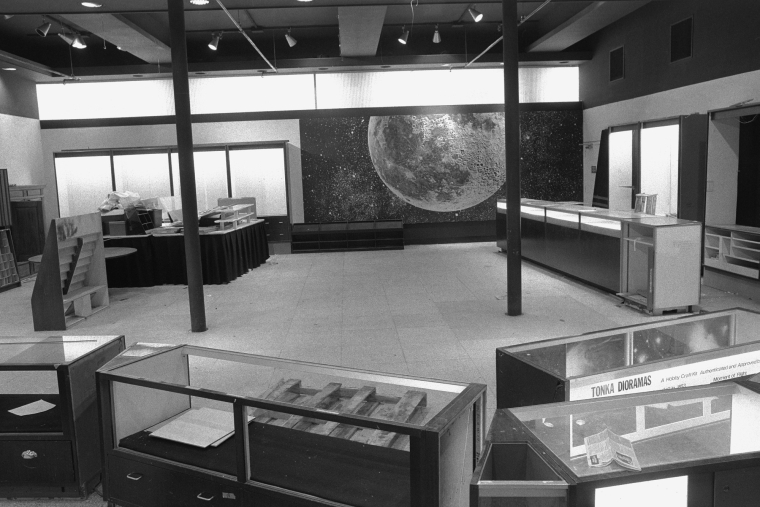

Even if it can be more or less decolonised, the museum has been discussed in the last few years as an institution that cannot avoid being marked by colonial history and by the colonialism inherent to certain ways of collecting, cataloguing, archiving and exhibiting.

Ana Balona de Oliveira

Susana Gaudêncio

When we talked to Teresa Fradique, she spoke about trying to live in another type of ontology than the Western one. And she gave the example of some African thinkers that have obviously also spent time within Westernacademia, like Achille Mbembe. To help to dismantle the idea of White privilege and the hegemonic vision of the construction of history, and let them build that discourse. A new discourse on contemporary life.

Ana Balona de Oliveira

I agree. We need to deconstruct fake universals,and recognise that historically other practices and knowledge have always been produced, like critical visions of the Western world for instance, also from within.

Susana Gaudêncio

Actually, when you talked about the margin you answered the question she raised. All are possible strategies.

Ana Balona de Oliveira

There are collectives, individuals and voices that do not want to occupy the centre, they don’t want to go to the museum, they want to question the museum institution itself and form other institutions – which doesn’t mean that the museum will disappear and that it cannot be deconstructed, questioned and transformed from the inside. Even if it can be more or less decolonised, the museum has been discussed in the last few years as an institution that cannot avoid being marked by colonial history and by the colonialism inherent to certain ways of collecting, cataloguing, archiving and exhibiting. But there are other types of strategies, other more horizontal and not-for-profit institutional models. This doesn’t mean that commercial transactions don’t have a role from the point of view of the many artists that need to sell their work for their own economical survival. These questions are complex in the art scene but going back to that more macro perspective, more radical questioning is necessary, which implies a radical life change and that has to do with capitalism itself. This immediately puts into question the art market itself and the neoliberalisation of academia. We can’t think in depth about the history of colonialism and slavery without considering how they were established to serve the capitalist project and, at the same time, how they were whitened by a Eurocentric vision of modernity, that meanwhile has been extended globally. This more radical and deep questioning encompasses everything that we have discussed today about artistic circuits, the market, institutions as well as ways of life and producing knowledge, specifically artistic. This structural perspective is our real horizon of action. And we are all implicated, including, of course, the people that work in the contemporary art scene.

Ana Balona de Oliveira is a CT Researcher (CEEC 2017) at the Institute for Art History of the New University of Lisbon (IHA-FCSH- NOVA), where she co-coordinates the research group Transnational Perspectives on Contemporary Art. She is also Collaborating Researcher at the Centre for Comparative Studies of the University of Lisbon (CEC-FLUL), and she has lectured in Portugal and the United Kingdom, where she received her PhD (Fort/Da: Unhomely and Hybrid Displacements in the Work of Ângela Ferreira, c. 1980-2008, Courtauld Institute of Art, 2012). Her research focuses on colonial, anti-colonial and postcolonial narratives, migration and globalisation in contemporary art from lusophone countries and beyond, from an intersectional and decolonial feminist perspective. She has contributed articles to many periodicals, including Nka: Journal of Contemporary African Art, Third Text, African Arts; coedited the volumes Diálogos com Ruy Duarte de Carvalho (2019) and Atlantica: Contemporary Art from Angola and its Diaspora (2018); contributed essays and interviews to the exhibition catalogue Recent Histories: Contemporary African Photography and Video Art (2017), and the volumes Revolution 3.0: Iconographies of Radical Change (2019), (Re)Imagining African Independence: Film, Visual Arts and the Fall of the Portuguese Empire (2017), Red Africa: Affective Communities and the Cold War (2016) and Edson Chagas: Found Not Taken (2015), among others. She curated the exhibitions António Ole: Vital Matter (Movart, Lisbon, 2021), Ângela Ferreira: Underground Cinemas & Towering Radios (Galeria Avenida da Índia, Lisbon, 2016), among others; and organised the talk series Thinking from the South: Comparing Postcolonial Histories and Diasporic Identities through Artistic Practices and Spaces (Hangar, Lisbon, 2018) and Artistic Migrations in and beyond Lisbon (Hangar, Lisbon, 2015- 2016).

“Empty Exhibit Cases” gathers three cisgender white women working in the arts, Susana Pomba, Susana Gaudêncio and Maribel Mendes Sobreira, on their way to become life-long anti-racist and effective allies, as artists, teachers, researchers, curators, historians, writers, or authors. The project delivers a group of essays (in diary mode), that might be hybrid in form, and attempt to dissect various questions and struggles, all in the context of the daily personal and professional lives of the three participants. They will also engage in conversation with activist groups, scholars, or cultural agents.

Based on diary-keeping as a form of writing, the Mode Diaries initiative creates a field of interpretative potentialities within the context of maat Mode 2020, a public, experimental and participatory exhibition and activity programme under the motto “Prototyping the museum”. This is the scope that justifies and enables the twisting of the meaning commonly attributed to the term “diary” by transforming what’s individualised into collective, private into public, singular into plural, etc.